Roland Smith

THE LIBERAL CASE FOR 'LEAVE'

The EU referendum campaign is presenting us two competing choices. On the one hand a vision of Britain as part of a steadily-integrating EU (at whatever speed) or a vision of Britain completely outside it.

For the Remain side, we are required to anticipate what may happen over the next generation which, if the last 40 years are anything to go by, will mean a gradual growth of EU power into more and more areas of competence - the ratchet towards “a country called Europe”.

The vision of Britain outside generally uses a number of arguments employed over a long period: of the need to regain our sovereignty and become a self-governing democracy again; to have the flexibility to deregulate; to spend the UK’s EU contributions on something better inside the UK; to drive forward better trade deals with countries beyond the EU; and to constrain immigration.

However let’s take this from a different angle and set out a third vision - a Leave proposition that rejects some of the arguments outlined above. In short, a liberal case for Leave.

In mapping out where this country should go to, one should first consider where it came from and why. We are, after all, a member of the EU so one might ask the question: If it was so awful, why did we join in the first place and why is there still a significant lobby supporting it? Those questions are pertinent not least because it’s sometimes said that if the UK government was proposing to join the EU today, the British would reject it by a large margin.

Let’s bypass the line that says the UK electorate were sold the then EEC on a false premise. Instead let’s look at the circumstances in Britain around the time we joined the EEC and then agreed to stay as a result of the 1975 referendum.

Back then Britain was a country beset by nagging economic problems that were coming to a head: The constant stop/go policies of the post-war period that seemed to only inch us forward while the likes of Germany and Japan seemed to leap ahead; strikes; power cuts; rations even; union power; consensus politics; corporatism; and the 3-day week. Opinion favouring free markets was out on the political fringes.

On a longer view, Britain was a country in decline. Since World War II and particularly since the Suez crisis of 1956, Britain’s empire and its confidence had declined as it grappled with a new post-imperial future. The USA and the Soviet Union were the two blocs that now mattered in the world, each having their own large economic trading zone (the USA itself and Comecon).

Indeed, large and protected blocs seemed to be the future and the EEC was apparently forging a third bloc and third way between these two giants, albeit aligned to the USA.

Then there were the walls.

The most visible walls were the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain separating the Soviet Union from the West but there were also significant tariff “walls” between blocs, countries and trading areas. These walls not only demarcated different geographic areas, they reinforced the separateness of those areas, limited trade, and ultimately put a limit on economic progress. The tariff walls in particular defined economic blocs but also made the case for them, creating an impulse for relatively like-minded countries to club together to at least forge a level of economic freedom among themselves.

Among British social attitudes at the time, there was a rich seam of opinion that defined ourselves against others. Each nationality and race had an unflattering nickname. Schoolboy jokes often centred on racism and xenophobia. On television, popular shows were the racist “ The Black and White Minstrel Show”, “Love Thy Neighbour”, “The Comedians”, and somewhat satirically “Till Death Us Do Part”.

The flip side of all this was the increasing trend of taking holidays abroad. Steadily improving living standards helped drive this trend but so too did growing competition in the airline industry, with Sir Freddie Laker’s Skytrain being a pioneer of cheaper air fares. The favoured destination for most Britons was Spain and, if you were particularly exotic, the Balearic Islands.

Indeed, “economically advanced”, and “exotic” were the main words one would think of when considering “Europe”.

This then was the backdrop to the UK’s entry into the EEC in the early 1970s and its confirmation in a referendum in 1975.

Being “for Europe” symbolically represented a future, outward-looking, cosmopolitan and internationalist mindset. It confirmed that you were part of the new jetset or had aspirations in that direction. It was about “getting on”.

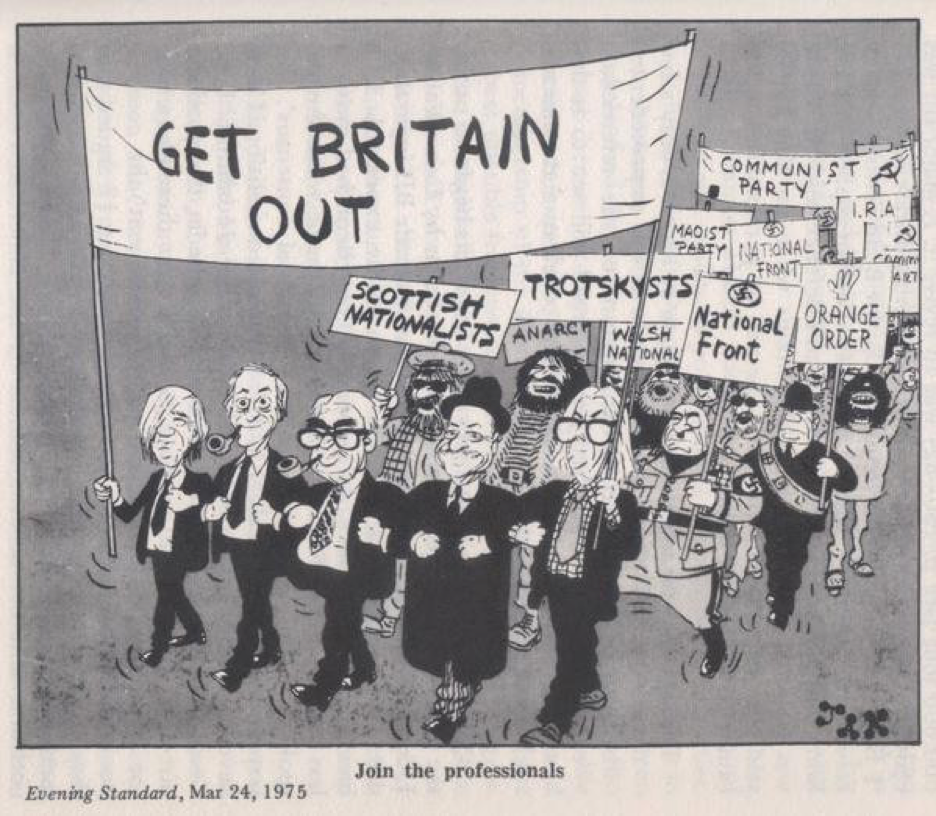

Conversely, being “against Europe” seemed to mean you wanted to cling to the old or existing ways that were failing; that you were parochial, old fashioned , narrow-minded, unreasonable even, and the fact that the more extreme ends of the political spectrum were “against Europe” — a coalition of Tony Benn and Enoch Powell — just reinforced this narrative.

There was a whiff of Colonel Blimp surrounding the Outers. Basil Fawlty’s passing comment in a 1975 episode of the BBC’s “Fawlty Towers" that he voted against EEC membership further reinforced that “anti-Europeans” were barking mad, stuck in the past, and wanted to re-fight old wars.

That narrative has largely stuck ever since: Of Pro-EU people being more enlightened, younger, more liberal and largely more educated than their anti-EU counterparts. That’s despite some very dramatic changes that have subsequently happened in the EU and in the world, sometimes behind the scenes. It is the contention of this paper that the backdrop has changed so markedly that those old assumptions have been turned on their heads.

As we now know, the 1970s turned out to be an odd period where many things that seemed like good ideas at the time turned out not to be. Indeed the whole “post-war” mindset from the 1950s up to the 1980s means very little now. It’s another culture that we can barely understand just several decades later and now look upon with open-mouthed incredulity, as Channel 4 recently highlighted in their toe-curling series “It was alright in the 1970s”.

While there may have been an element of truth about EEC membership in the 1970s that seduced many subsequent sceptics— the blocs, the global tariffs, the strife and decline in Britain — we can now say that our timing for joining “the club” could not have been worse.

Poor timing: The black vertical line is when the UK joined the EEC/EU

Events started changing the political and social climate in Britain very soon after we joined.

The first big change in the climate surrounding EEC/EU membership came during the 1980s with some significant (and unwelcome to some) changes in Britain under Margaret Thatcher. Towards the back-end of that period came the second significant change: the Soviet Union started creaking and then collapsed along with the Berlin Wall (1989) and later Yugoslavia (from 1991).

Around this same time we saw the Delors speech at the TUC conference followed by Thatcher’s speech to the College of Europe in Bruges (both 1988). And then came the Maastricht Treaty, the Danish No vote, and sterling’s exit from the exchange rate mechanism in September 1992.

All of these served to change the backdrop to the EU membership debate. In fact the commentator Wolfgang Münchau has named this period, specifically the Maastricht Treaty, as the time when Britain began its long slow exit from the EU.

But another less well-known and less reported event in the early 1990s has profoundly affected the logic (or lack of it) behind Britain’s EU membership.

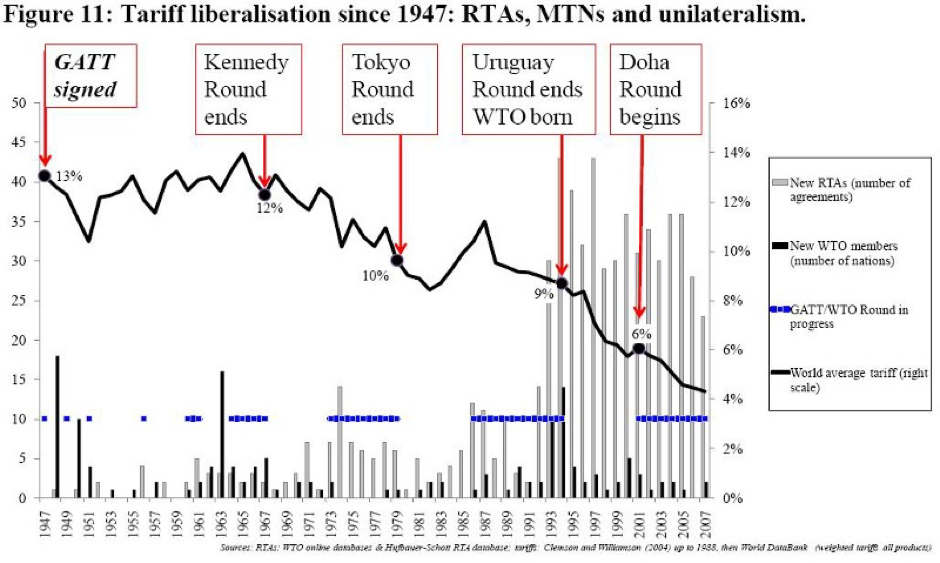

This was the Marrakesh Agreement that gave birth to the World Trade Organisation (the WTO). The agreement was forged in the early 1990s following 12 years of negotiations and finally confirmed on 1st January 1995. This agreement represents the moment globalisation was born. It didn’t take long for a new phenomenon of G8 protests to take hold.

Tariffs were then steadily reduced and “globalisation” — the word and the reality — began to take hold.

Note the fluctuating-but-consistently-high average tariff up to about 1972…

The start of this massive global tariff reduction and freeing up of global trade just happened to coincide with the emergence of many new nations.

And it was a coincidence, but in different circumstances it might not have been. As an Institute of Economic Affairs paper separately observed in a discussion on states and other political entities in a globalised world:

“Now suppose trade barriers are reduced. This shifts the equilibrium: it is now possible for people to be part of the same economic area, without having to be part of the same political entity. They are able to trade with one another without having to agree on politics. This means the economic benefits of large markets can now be reaped without incurring the political cost of heterogeneity. Consequently, the optimal size of a political entity falls.

This is an exact reversal of the conventional rationale for EU-federalism, which holds that globalisation makes larger political entities necessary. Au contraire: it is the very globalisation that makes smaller political entities viable.”

Unseen and barely discussed in the 1990s, globalisation was beginning to eat into the logic of a political European Union at the very point it was striding towards statehood with a single euro currency.

Looking back, the EU was (and is) an old ideology in a hurry.

The event that was somewhat more attuned to freer globalised trading was the fanfare around the launch of the single market in 1992, except for the fact that it was and is tied to the EU’s political integrationist ambitions. But now, even the European single market is being rapidly eclipsed by the march of globalisation. A large and growing body of single market law is now made at global level and handed down to the EU which in turn hands it down to the member states.

The automotive industry’s standards are defined by the World Forum for the Harmonisation of Vehicle Regulations (known as WP.29) under ‘UNECE’ - a United Nations body. Food standards are defined by the ‘Codex Alimentarius’ established by the UN and the World Health Organisation. Modern labour regulations are defined by the ILO – the International Labour Organisation. Maritime regulations are defined by the International Maritime Organisation. Many energy-related regulations can be traced back to the global Kyoto accord on climate change and other international agreements.

And so it goes on.

Through the 2000s, some service industries including financial services lagged behind in this globalisation process just as they do at EU/single market level. But in the aftermath of the “global financial crisis” the shift to a globalised market with globalised regulation accelerated, with the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the OECD and the G20 (Financial Stability Board) taking key roles.

In February 2015, a House of Lords report on the “post-crisis EU financial regulatory framework” noted that:

“… it is likely that the UK would have implemented the vast bulk of the financial sector regulatory framework had it acted unilaterally, not least because it was closely engaged in the development of the international standards from which much EU legislation derives.”

At the global level, regulations are made on a consensus basis and sometimes involve other non-state actors and NGOs. It is not done by crude majority voting. The final agreements then percolate into national (non-EU) law and also into EU Directives and regulations.

The EU is therefore increasingly becoming a pointless middleman as a vast new global single market takes over. Indeed when faced with newspaper headlines about the latest daft EU regulation, one now has to check where they ultimately came from and whether other countries around the world are doing something similar. That will give the clue to a regulation’s global origins. Almost all ‘silly regulation’ stories about food standards usually originate from bodies above the EU.

With such a backdrop, one or two things have become very clear.

For example, the idea of the EEA (European Economic Area) being a stepping stone to full EU membership is finished. Pro-EU forces in Norway and Iceland have effectively or actually shut up shop. Of course that doesn’t stop pro-EU voices from those countries making interventions in the British debate in order to help prop up the EU.

However as every year passes, these nations have less and less need for that much vaunted “influence within Europe” as some of their politicians acknowledge. As an independent nation Norway has a seat at these global top tables alongside the EU and alongside other nations of the world and that’s where Norway exerts its influence. The standards and regulations are hammered out through intergovernmental cooperation but stuck inside the supranational EU, the UK is effectively neutered on many global bodies courtesy of the EU’s common position. It is one of many ironies of the current debate that the pro-EU position is to stay in the EU to be “at the top table” shaping the market. The case to leave the EU is quite similar—to be at the “top table” shaping the market. The difference is knowledge of where the top table is located these days.

But it also means that the “bonfire of regulations” wanted by some Leavers is not going to happen to the extent they expect. Global regulation will still be there - increasingly so. The positive aspect to this situation is that it will provide a stable regulatory environment during and after Brexit.

That’s not all.

Globalisation has already made geography largely irrelevant. So has technology and the internet.

We are now less dependent than ever on our closest trading partners in Europe and this trend is marching relentlessly onward. For the first 40 years of our membership, the majority — over 60% — of UK exports went to the EU. But in 2012, for the first time, that figure dropped below 50%. It is now at 45% and continues to sink.

UK exports to the EU

The demographics of the European continent, alongside the dysfunctional euro and its insidious effects across Europe have also played a large part in this change, but so has the resurging global confidence of Britain. The London 2012 Olympics may yet come to be seen as a timely and fitting symbol of a nation’s re-emergent global ambition.

This situation and these trends are not going to change. They are only going to continue and where economics goes, politics generally follows. Eventually.

There are still some obstacles that need to be considered as part of Britain’s EU exit and full re-engagement with the world. For example, global tariffs have diminished but in so doing, a swathe of non-tariff barriers (NTBs) or ‘technical barriers to trade’ (TBTs) have been revealed — essentially regulatory differences between countries/zones that impede entry of a product, service or company into that country or zone. Tariffs are thus no longer the issue they once were; TBTs are.

For example, while US motor vehicle exporters face EU tariffs averaging eight per cent - 10 per cent on finished vehicles and 3.0- 4.5 per cent on most parts - the estimated cost of TBTs in this area is equivalent to a 25.5 per cent tariff.

But firstly TBTs are a consideration for Britain’s method of exiting the EU, they do not prevent it. And secondly TBTs are being addressed globally over time.

To avoid disruption and to maintain full access to the EU/EEA market after the very narrow two year window provided by Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union, Britain’s exit from the EU would necessarily be a journey out not a one-time event.

We would likely first move to a single market position outside the EU using the EEA framework as a model. In other words, still in economic union but not in political union. That would create a trade-based counterweight to the EU in Europe and may well draw other EU member states out to that position. The journey would continue from there, ending in a position as a regional player in the global single market, leveraging our historic connections around the world.

What the Remain campaign describes as the UK’s “isolation” outside the EU will actually mean freedom to make alliances depending on the issue and our expertise and interests in it. It will initially give us continuity, not least through the principle of continuity for the EU’s existing third country trade agreements, but it will also start to introduce agility and allow us to be fully heard at global level.

The moment of Brexit is therefore a turning-the-ship event; it is not the final destination. Accept that and much else falls into place. One might add that if ‘Leave’ were to win the referendum, it would be the Conservative government (over half of whom are Remainers) advised by the civil service that will manage the aftermath. It will not be the Leave campaign. The method of exit will therefore be evolution – the art of the possible – not revolution.

So there is an inevitability about all this. The issue is not going to go away, even if the UK votes to remain in the EU in June. The forces of globalisation alongside the EU’s internal issues born from its “one-size-fits-all” mentality mean the stresses in the EU-UK relationship will only increase. It may become a simple case of leave now or leave later. But leaving later just defers the inevitable and may well be worse when it comes.

Maybe Münchau was right when he suggested Britain’s long slow march away from the EU started back in the 1990s when we opted out of the euro.

But where is the issue of migration in this vision? There have always been wars in distant lands but with some exceptions, this hasn’t necessarily meant a huge influx of migrants into Europe or the UK.

The United Nations has reported that in 2010 there were 214 million migrants around the world — an increase of 37% in just two decades. Observers of this subject suggest there’s more mobility now than at any time in world history.

One answer is that migration is possibly the third wave of globalisation, after goods and capital. Migration isn’t regulated in the way that goods and capital are but people in less developed countries are increasingly aware, if only in a vague sense, of an attractive world elsewhere especially when their country is constantly at war. Others elsewhere may have been impacted/employed by an international company in their country that exported back to the western world. They know that there are ways and means to move and settle elsewhere and that the economics of immigration in the receiving country (especially if in poor shape demographically) will often triumph.

Even after high immigration, Germany’s population pyramid is still in bad shape

The other aspect to this is that the ‘refugee’ migration that has caused so many issues in Europe is regulated by the 1951 UN Convention relating to the status of refugees, along with an 1967 amending protocol both of which are arguably out of date.

It would be ironic that an out of date convention is troubling an out of date EU, both born in the same out of date post-war period.

Without going too far into the rabbit warren that is the subject of migration, if one accepts increasing globalisation, one must accept the corollary of a high degree of migration. And manage it. If we as country regain the power to decide these matters, we can at least start having a grown-up debate about it which would be a major advance on where we are now. Immigration has brought great benefits to this country, but that is one side of an argument and a decision that should be openly debated by the people of this country, without the fact of EU membership infantilising the debate by prohibiting a large part of that decision. Given Britain’s historic, open and global outlook, it is likely that a majority of the British would opt for a policy not far from where we are now. But it would at least be seen as democratically legitimate and would therefore be put on a much more solid footing. Indeed a recent Migration Watch study suggested that even with a post-exit deal that also leaves the Single Market, EU migration would fall by about 100,000. In other words it would only put total net migration back to near the average for the last 12 years – about 240,000 – an average that prompted calls for “border control” in the first place. And that’s before one factors in some UKIP calls for an increase in Commonwealth migration after exit.

As for this country’s identity — it has withstood far greater threats than 13% of the population being foreign-born. One might add that Switzerland and Australia with much higher proportions of migrants seem to manage OK. As the British Olympian Mo Farah shows, newcomers usually come here because they love this country and its culture and can even pick up its timeless sense of self-deprecating humour (the famous “Mo-Bot”). The country and its institutions are too powerful to be “over-run”, and fear of this happening displays a misunderstanding of what Britain is about — ironic given that those most of those advancing this view claim to be the most British/patriotic.

This Brexit vision is therefore a global, outward-looking and ambitiously positive one. It eschews the inward-looking outlook of both the Remain lobby and the shouty anti-immigration lobby.

So a parochial inward-looking “little Europe” and a demographically declining one, ranged against an expansive, liberal and global outlook. This vision certainly doesn’t want to go back to the past: of barriers, blocs, and narrow-mindedness.

The crux of the matter is that we in Britain want trade and cooperation; our EU partners want merger and a leashed hinterland. Are we prepared to spend another generation or more dancing around this basic fact while the rest of the world moves on?

No, it is time to leave and embrace the world.