We might be at the right level of smoking regulation

Usually the costs of something rise as you do or have more of it, while its benefits fall. So unless the cost of the first unit is already very high or the benefits of the first unit are already very low there is some amount greater than zero that it is optimal to have or do. This is true for an individual and for a society. The first car you have massively changes your life. The second one adds pleasure, variety, and a good deal of practicality in some situations, but it's much less useful than the first. Nearly no one has three cars to themselves because the benefits are vanishingly small and the cost is rising for storage, upkeep reasons.

The first few million cars in a society the size of the UK are amazingly useful, the next million go to people who don't need them as much but do add to congestion, pollution and so on. The forty-millionth or sixty-millionth car starts taking up way more space than it's worth.

Well as the title suggests I think it's possible we might be approaching (or already have gone past) this point when it comes to smoking regulation. I wrote before about how plain packaging was probably a mirage (incidentally I learned today that the UK would drop three whole places, from 2nd to 5th on the GIPC's index of intellectual property rights protections if it passed it; though many of this blog's readers probably wouldn't mind that).

We may have needed very activist laws in the past because it really is quite difficult to inform people about anything really, and smoking is dangerous in important ways such that if you don't understand the decision you're taking you really could make your life a lot worse. But nowadays people may well even overestimate the costs and people are thus taking the right decisions to maximise social utility. It isn't a question of externalities because smokers actually cost the state less by dying earlier (a bad thing!)

This isn't just a musing. A new paper in the Journal of Cost-Benefit Analysis ("Retrospective and Prospective Cost-Benefit Analysis of US Anti-Smoking Policies" (pdf) by Lawrence Jin, Donald S. Kenkel, Feng Liu & Hua Wang) says roughly the same.

We use a dynamic population model to make counterfactual simulations of smoking prevalence rates and cigarette demand over time. In our retrospective BCA (Benefit-Cost Analysis) the simulation results imply that the overall impact of antismoking policies from 1964 – 2010 is to reduce total cigarette consumption by 28 percent.

At a discount rate of 3 percent the 1964-present value of the consumer benefits from anti-smoking policies through 2010 is estimated to be $573 billion ($2010). Although we are unable to develop a hard estimate of the policies’ costs, we discuss evidence that suggests the consumer benefits substantially outweigh the costs.

We then turn to a prospective BCA of future anti-smoking FDA regulations. At a discount rate of 3 percent the 2010-present value of the consumer benefits 30 years into the future from a simulated FDA tobacco regulation is estimated to be $100 billion. However, the nature of potential FDA tobacco regulations suggests that they might impose additional costs on consumers that make it less clear that the net benefits of the regulations will be positive.

Especially cool is the chart of a rational level of cigarette smoking, based on the benefits to the smoker of fulfilling their preferences vs the costs of frustrating their preferences for better health and a longer life.

I'm not saying that this research is conclusive. One paper is one paper. But I think it's getting to the point where further cigarette regulation is becoming intrusive and costly without necessarily producing large benefits to its purported targets. We should consider if we've maybe hit the cigarette regulation sweet spot.

We're all in favour of the empowerment of women, however....

It is rather necessary to get things the right way around. This following quotation gets it the wrong way around:

There is a plethora of data which demonstrates that women’s economic participation grows economies, creates jobs and builds inclusive prosperity.

Actually, there is no evidence of that at all. What there is is a great deal of evidence of a correlation between an advancing economy and greater, leading to equal, rights for women. But as we all know, correlation and causation are not the same thing.

We maintain that the causation actually works the other way around. It is an advancing economy that leads to greater rights, leading to that equality, for women.

To take two very basic examples. The aim and pupose of life, assuming Darwin was right, is to have grandchildren. It wasn't that long ago (and is still true in the more benighted parts of the world) that a woman would need to have 6 to 8 children in order to be able to have some reasonable guarantee (absent some dreadful plague that carried them all off) that grandchildren would arrive. In turn this meant spending almost all of fertile adult life either pregnant or suckling: and even after that not a great deal of time for anything else. Once child mortality fell, as blessedly it has done for us and is doing for the more benighted, then the number of children necessary falls and so therefore does fertility. Freeing up that time for that greater equality and so on.

Secondly, consider a poor economy. It is, almost by definition, one reliant upon human and animal power. And women are, we've all noted, rather lacking in that muscle power as compared to men. Thus that traditional division of labour between the sexes. One sex does the heavy lifting out in the money economy, the other does the just as difficult, just as boring, but physically lighter work in the household. Once we move on from muscle power to machine that greater economic equality is actually possible: and it happens.

Telling women in a subsistence agricultural economy about empowerment is therefore a bit of a swiz. What is necessary is to get out of being a subsistence agricultural economy and the empowerment will naturally follow.

There's no doubt that there's a correlation between this capitalist/free market economic growth and women's empowerment. It's just that it's the growth that causes the empowerment, not the other way around.

All the more reason to support that economic growth of course, for we all most assuredly desire the empowerment.

Economic Nonsense: 22. Only by understanding the causes of poverty can we act to reduce it

This assertion is nonsense because it erroneously supposes that poverty has causes; in fact it is the lack of poverty that has causes. Poverty is, alas, the default condition. It is what happens when you do nothing. Anyone who wants to experience poverty has only to do nothing for a year. If they survive that long, they will be poor, poor because they have not done the things it takes to create wealth. Poverty has unfortunately been the lot of most of humankind for most of its existence. First by hunting and gathering, then by agriculture and animal husbandry, people have lived on the edge of survival, always striving to obtain their food supply. If they had a few bad days at hunting, or a bad harvest at farming, poverty would come, bringing malnutrition and death with it.

At some stage people developed trade, exchanging goods with other, sometimes distant peoples. They learned how to specialize and to generate wealth. With the Industrial Revolution our ability to do this multiplied enormously. Wealth was created on an unprecedented scale, and for most people in the richer countries extreme poverty has become a thing of the past.

Other nations that have followed the same route have achieved similar progress themselves. Only in the past few decades has wealth been multiplied in poorer countries. First Japan became rich, then the 'tiger' economies of South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Following them have been countries such as Malaysia and Thailand, and most dramatically of all, the giants of India and China, lifting over a billion people out of poverty.

To move out of poverty takes trade, specialization, investment and infrastructure. It takes stable property rights, clear titles to land, efficient and honest courts, and governments that are neither predatory nor rapacious. These are the conditions under which people find space to improve their lot and to create wealth. Failure to achieve a reasonable measure of these will keep a country in poverty. Poverty is not caused by things people do, but by things they fail to do.

There's no tradeoff between 'quality' and quantity of kids

One of the key elements of human capital theory is the idea of a trade-off between having more, lower 'quality' kids and fewer higher 'quality' kids. That is: having more children and having less money to spend on their education, healthcare and so on, leaving them with less human capital (anything that makes their labour more valuable), or having fewer kids and having more money for all those things. You can have two high-achievers or ten low-achievers, the theory would go.

We know there was a demographic transition first in Northwest Europe then in all developed countries and even now some developing countries. This saw fertility crash down to where it stands now—only about replacement value (and much lower in some places like Japan and Russia). One theory holds that this explains part of the industrial revolution: parents have fewer kids but invest more in the ones they do have, leading to more smart tinkerers, scientists, skilled workers and so on—and faster growth and more wealth.

A new paper from two of my favourite economic historians, Gregory Clark of UC Davis, and his regular co-author Neil Cummins (I blogged on some of his other work earlier) of the LSE, tackles this question by looking at the mindblowingly productive surnames database they have already mined to effectively overturn the entirety of existing social mobility research.

The paper, entitled "The Child Quality-Quantity Tradeoff, England, 1750-1879: Is a Fundamental Component of the Economic Theory of Growth Missing?" (pdf, excerpts), fits into the usual Clark/Cummins mould. It's well-written, clear, filled with hugely interesting tidbits, and it overturns popular but flawed views. Here they argue that the Industrial Revolution and gigantic rise in wealth and living standards since the 1700s (or even the 1600s) cannot be down to a quality-quantity trade-off in kids because kids in bigger families had life outcomes indistinguishable from kids in smaller families.

A child quantity/quality tradeoff has been a central to economic theorizing about modern growth. Yet the evidence for this tradeoff is surprisingly limited. Measuring the tradeoff in the modern era is difficult because family size is chosen endogenously, and family size is negatively associated with unmeasured aspects of family “quality.” England 1770-1880 offers an opportunity to measure this tradeoff in the first modern economy. In this period there was little association between family sizes and family “quality”, and if anything this association was positive.

Also completed family size was largely randomly determined, varying in our sample from 1 to 18. We find no effect of family size on educational attainment, longevity, or child mortality. Child wealth at death declines with family size, but this effect disappears with grandchildren. The switch in England in the Industrial Revolution to faster growth rates thus seems to owe nothing to declining family size.

This isn't quite true for wealth, as they say; spreading inheritances among 10 siblings meant less for those 10 than if they had been five or two. But by the next generation (grandchildren of the original parents) this difference evaporated entirely. Isn't this a surprising fact when people claim that the children of the rich turn out rich because of the cash they inherit? It's just very very hard to pass wealth on through human capital investments (this seems to be one of the key truths of economics).

Most economics papers are not worth reading the whole way through but here I would definitely recommend it.

239 years of The Wealth of Nations

Today is the 239th anniversary of the publication of The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith. For nearly a quarter of a millennium, we have actually known the principles by which wealth is created and maximised. The trouble is, that for a fair chunk of the same time, we have been trying to resist that information, thinking that we can somehow do better than the market. The Wealth of Nations is a great book: most objective commentators would probably put it among the top five books ever written, in terms of its influence on humankind and the way we live.

Yes, it's very eighteenth-century stuff, sprawling and wordy, with enormous digressions on things that do not seem very interesting to us today. Luckily, you do not have to read it, because you can download my Condensed Wealth of Nations instead.

And yet, Adam Smith's original is the book which took economics out of its primitive phase and made it distinctly modern. With a bit of time and effort, any of us can understand what Smith says because what he is describing is all around us today.

The very first sentence of the book dismisses the old idea that the wealth of a nation was the amount of gold and silver that it had hoarded up in its vaults. Rather, says Smith, the measure of a country's wealth is what it produces. In that first sentence, he had invented the idea of gross domestic product. In the second, he notes the wealth of individual citizens of that country depends on how many citizens are sharing this GDP. (So there,he had invented the idea of GDP per capita.) In the third, he talks about how many people are actually working to produce this wealth. (The concepts of the participation rate, and productivity.) Before we are past the first page, we can see that this is sensational stuff.

But surely his greatest breakthrough was the realisation that we do not have to conquer people or make things in order to increase our wealth. We can also increase it by simply exchanging things. If you have something I want and I have something you want, we are both better off by swapping it. And that is the foundation of market exchange and trade, and of the specialisation that makes our production and exchange system so spectacularly efficient, creating and spreading benefit throughout the world.

Teachers unions are bad for kids

Though everyone typically sees unions as being mainly for the benefit of their members, teachers' unions use a lot of pro-student rhetoric and often come across fairly angelic. They probably do have only the kids' interests at mind, but a new paper suggests that their existence doesn't necessarily benefit those kids.

Data comparing students' outcomes to teacher unionisation has until recently been fairly lacking. But according to the new study published last month, duty-to-bargain laws (which mean employers need to work with unions) lead to significantly worse labour market outcomes for students in schools subject to them.

Previous research has shown us that teacher collective bargaining laws increase teacher union membership and increase the likelihood that a school district unionises for the purpose of collective bargaining—i.e. they achieve their direct goals. But looking into the effect on the kids has been hampered by a lack of information liking people’s outcomes and the time that duty-to-bargain laws were passed.

This new study, conducted in the US by Michael F. Lovenheim and Alexander Willen, takes the timing of the passing of the duty-to-bargain laws between 1969 and 1987 and links them with long run educational and labour market outcomes among 35-49 year olds in 2005-2012, i.e. those subject to them..

What they found was that men subject to increased unionisation work less hours as adults and earn less. There is also evidence of a small decline in educational attainment for men and a long-run negative effect on labour supply for women that is equal in magnitude to that of men.

Of course, some of the kids tin this paper were subject to a vastly different educational environment than exists today, so we can't necessarily extrapolate to the UK. Nonetheless the general finding is quite plausible, and should contribute to policy debates around increasing or reducing the role of collective bargaining in the education sector.

If future research in this field continues to make the negative relationship apparent, we may be ever closer to exposing how teaching unions lower educational standards by supporting the timeservers over the strivers in the teaching profession.

More evidence that all schools should be free schools

Free schools raise standards - not just in the schools themselves, but in the traditional state schools in their neighbourhood. That is according to a new report from the think tank Policy Exchange. And it should come as no surprise. That is exactly what happened in Sweden, after it reformed its education system in 1991 and allowed charities, faiths, voluntary groups and private companies to open schools rather like the UK's free schools.

Schools that are independently run but still supported by taxpayers – and paid by results, basically in proportion to the number of pupils they attract – are better motivated to think more deeply about the education they provide and how they provide it. Despite the fact that free schools are still highly regulated – much more so than their counterparts in Sweden – that is exactly what they do. So they stimulate other, unreformed, schools in two ways. First, they provide a model for what is achievable. Second, local state schools realise that they have to improve if they are to continue to attract pupils and justify their own existence. Simple really.

People make two arguments against free schools. First, they say that they are more selective than other schools and so it is not surprising that they get better results because they get more able pupils from generally better-off, better-educated parents. But look at another country, the United States, with its so-called charter schools. Often, these have been set up in the least promising areas, inner-city areas rife with drugs and violence, where all or nearly all pupils are from generally poor, minority families. The uplift in performance, though, is startling. Many of these schools are set up by parents, or parents and teachers, precisely because the existing government-run schools are do depressingly and young-life-ruiningly dismal. but those concerned local people make their schools secure places to learn, ban drugs and tolerate 'no excuses'. And you know what? The children shine.

The other objection is that free schools in the UK are wasteful because they are often set up in places where there are already spare places in traditional state schools. Indeed: rather like the case in those American cities I have just mentioned. Setting up a new, different, better-motivated school in an area where there are only 'sink' schools is no waste: it is one of the most cost-effective things you could do. Preventing better schools from setting up is rather like preventing better restaurants from opening up when there are still spare tables in the local greasy-spoon.

The government says it will create another 500 free schools. Frankly, we should turn every school in the country into a free school.

Wilkinson and Pickett are, yes, still wrong

This would simply be laughable if it weren't for the fact that it's so dangerous. Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett are, once again, telling us that it's all inequality that fuels our woes. And yet they've entirely misunderstood the statistic that they're using to prove that this is so. And to add to the embarrassement Wilkinson at least is supposed to be a demographer, meaning that he really is supposed to know how badly he's cocking things up here. Yes, we're being rather fierce here but rightly so:

New statistics from the ONS have revealed that women in the most deprived areas of England can expect to have 19 fewer years of healthy life than those in the most advantaged areas. For men, the figure isn’t much better, with a gap of over 18 years. To put that into perspective, those born in the poorest parts of England can now expect to live the same, or fewer, healthy years as someone born in war-torn Liberia, Ethiopia or Rwanda. And a third of people in England won’t reach 60 in good health.

Those statistics are here. And the first part of the paragraph is correct. Ages at death in poorer areas, health before death in poorer areas, are lower/worse than they are in richer areas.

But this has absolutely nothing at all to do with life expectancy at time of birth. Simply because no one at all is even attempting to measure life expectancy at birth. What people are measuring is age at death, health before death, in certain areas.

The difference is, and you may have noticed this, people actually move around during their lives. Further, it is not (necessarily) true that income inequality leads to health inequality. For it is also true, as we've pointed out many a time before, that health inequality can and will lead to income inequality. That ghastly disease that cripples someone in their 40s is going to have an impact on their income during the remainder of their life. We cannot therefore look at income inequality and claim that it causes health inequality. Simply because there are two processes at work.

Further, we cannot look at lifespans in an area and insist that these reflect the life chances of those born in that area. Take, as an example, a retirement town like Bournemouth (say, any other will do). People often retire there at, say, 65. Can we then look at average lifespan in Bournemouth and correlate it to that of someone born in Bournemouth? No, of course we can't: for the average lifespan in Bournemouth is going to be boosted by including large numbers of people who only impact the numbers after they've survived to age 65. And, obviously, those rich enough to be able to move for their retirement.

This migration over lifetimes will lead to selection: the richer will go to richer areas (if nothing else on the grounds that they can afford the property prices) and the poorer will go to poorer areas. At least part of what is being measured is therefore the effects of this selection, not the life chances of those born in these areas. As such we simply cannot accept the conclusions they are making from this data.

And as up at the top, Wilkinson at least is supposed to be a demographer and he really is supposed to know all of this. It astonishes that they keep pushing this obviously incorrect line.

These statistics are compiled on the basis of LSOAs, lower super output areas. There's some 32,844 of these in England. That is, each LSOA is a unit of roughly 1,500 people give or take a bit. So, how many people die in the same 1,500 people strong grouping that they are born in? The geographical area inhabited by that same 1,500 people? Moving three streets over on marriage would take you out of such a small area.

Quite, somewhere between not very many and none these days. These statistics are simply valueless in trying to prove what Wilkinson and Pickett want to torture them into showing.

Logical Fallacies: 16. The gambler's fallacy

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJYaDv0Y1K8

Madsen Pirie's series of logical fallacies continues with 'the gambler's fallacy'.

You can pre-order the new edition of Dr. Madsen Pirie's How to Win Every Argument here

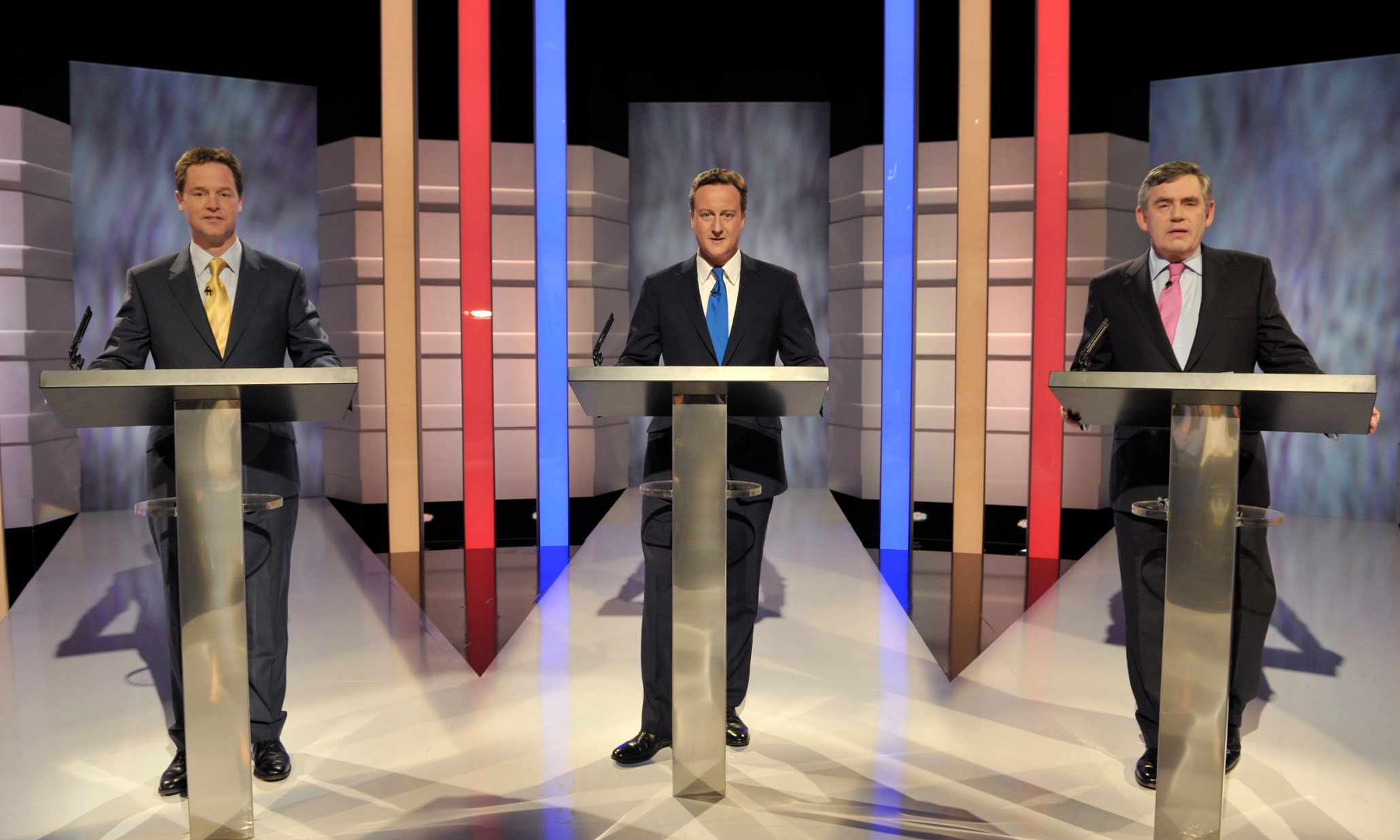

Ed Miliband's TV debates law

Following the TV debate row in the UK, Labour Party leader Ed Miliband says a future Labour government would pass a law to ensure that live television debates become permanent features of general election campaigns. The law would establish a trust to establish the dates, format, volume and participants. I was once shocked by the alacrity with which politicians proposed new laws as the answer to any problem. Then I came to see it more as an interesting fact of anthropology. Now I see it more as an art form. The invention that goes into making new, pointless or counterproductive laws is truly a pinnacle of human achievement.

It is sublime that a politician who cannot get other people to debate with him should propose a law to force them. Exquisite that this new law should be backed up and overseen by a new quango. Uplifting that the law's proponents should think that the process would be fair, democratic, and easy.

It won't, of course. As I have mentioned here before, it is by no means clear that TV debates have any place in the constitution of the UK. After all, we do not live under a presidential system, and we do not elect presidents at general elections. Rather, we elect individual Members of Parliament in our local constituencies, and it is those MPs, or at least their parties, who decide who goes into 10 Downing Street. TV debates, by contrast, suggest that we are in fact electing a head of government. They suggest that individual MPs are of no account, mere members of that person's Establishment. They suggest that we are electing an executive, not a legislature that can hold the executive to account. Already, the executive in the UK has far too much power over Parliament, and Parliament has too little control over the executive. TV debates can only make that imbalance more profound.

As for timing, who knows if the five-year fixed election cycle, introduced in 2010, will last? If parties split on key issues, for example, the country might find itself without a coherent government. The calls for a fresh election would be overwhelming. And how to decide who should debate anyway? Is it decided on the basis of current representation in Parliament (in which case UKIP, though polling 15%, would be nowhere)? Or on the basis of the polls (in which case the Lib Dems, currently part of the government, would be nowhere)? Should parties that stand in only part of the UK (the Scot Nats or the Ulster Unionists, for example) be represented in the national debate? If so, how deeply?

The only people who would win every time are the lawyers. I sometimes wonder if, like the mice in Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, it is actually for their benefit that the world is currently configured.