Addressing the Right Problem

Last month, in a somewhat bizarre throw-back to the 2010 General Election, Suella Braverman diagnosed one of the causes of Britain’s current woes; “There are too many people in this country of working age, who are of good health and also are choosing to rely on benefits.”

She is missing the central point. Britain is indeed on the verge of entering another recession, but unlike the 2008 down-turn, it is not one—at least yet—that is underlined by a high unemployment rate. In 2011, the unemployment rate reached a peak of 8.5%. In comparison, the UK’s unemployment rate currently sits at 3.8%, while the economic inactivity rate has also been in decline. Indeed, the Department for Work & Pensions has spent the last few months gleefully sending out press releases announcing how many more people they have helped into work.

Source: Office for National Statistics

This rhetorical appeal to ‘work-shy Britain’ also omits the fact that 40% of people on Universal Credit (UC) are employed, whilst 1.4 million people are claiming working tax credit. The cost of living crisis isn’t a symptom of a high unemployment rate; it is shining a harsh light onto the problem of in-work poverty.

When I talk about poverty, I do not mean ‘relative poverty,’ which is often how it is defined. Those living in relative poverty live in a household which has an income below 60% of the inflation-adjusted median income of a base year (usually 2010/2011.) Of far more use are more measures such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s conception of a minimum income standard, which is an annual calculation of the cost of items and activities we deem to be necessary for an acceptable standard of living in the UK. This is analogous to Adam Smith’s own conception of poverty in his Wealth of Nations:

“A linen shirt, for example, is, strictly speaking, not a necessity of life. The Greeks and Romans lived, I suppose, very comfortably though they had no linen. But in the present times, through the greater part of Europe, a creditable day-labourer would be ashamed to appear in public without a linen shirt.”

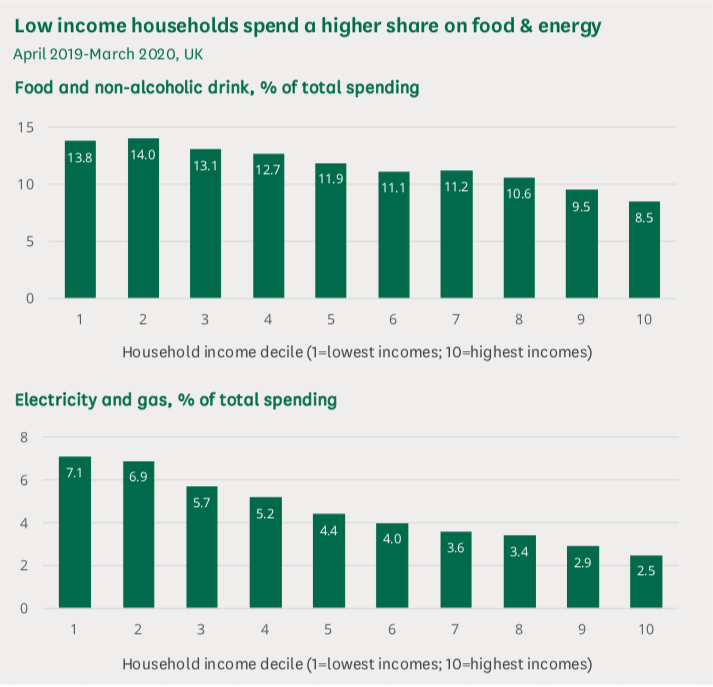

The inability of many people in work to afford items we would consider essential is precisely the problem; the price of food and energy are the top two reasons behind UK adults reporting an increase in their cost of living. Unsurprisingly, lower-income households are the most affected by rising prices as they spend a larger proportion of their income on energy and food. Worse still, lower-income households are facing inflation rates around 1.5 percentage points higher than higher-income households due to rising energy prices.

Source: House of Commons Library

Unfortunately, there are no immediate fixes. But there are a few reforms that the Government could enact to reduce in-work poverty. Firstly, it could help to reduce some of the higher costs facing workers through enacting supply-side reforms. This would include reforming our hideously outdated planning laws in order to drive down house prices, and relaxing child:staff ratios to reduce childcare costs.

Secondly, it could reduce the tax burden on workers. One simple way of doing this would be to index tax brackets, in particular the Personal Allowance, to inflation in order to eliminate fiscal drag.

Thirdly, it could seriously consider introducing a system of Negative Income Tax, (NIT), which would act as a minimum income guarantee, tapering away as peoples’ wages rose through work.

Fourthly, it could stimulate an increase in productivity, which is linked to workers’ wages, through replacing the super-deduction policy, thereby incentivising greater investment in capital. At present, the UK is forecast to be the slowest-growing economy in the G7 by 2023—if the Government is serious about wanting the UK to be a high-wage economy, this is something that needs addressing.

The outlook for those on lower wages over the next couple of months is bleak. The Conservative Party will not do itself, nor the public, any favours by complaining that Britons simply ‘aren’t working’ and reproaching a ‘culture of dependency’ which they have served to entrench through failing to enact necessary reforms for economic growth, rather than accurately diagnosing the problem.