Michael Strain's "The American Dream Is Not Dead"

In response to those on both the left and right claiming the American working class is being robbed by China or billionaires Michael Strain’s book delivers a passionate defence that opportunity and meritocracy still exist in America.

From longer holidays, to better cancer survival rates, to more affordable luxuries such as air travel, the standard of living of the average American has risen considerably since the 1970s and 1990s. He argues against the permanent hollowing out of the middle class by using Harry Holzer’s argument that a new middle class is emerging centred around jobs in healthcare, mechanical maintenance and some services. He also argues against the Conservative Populist argument that there are a record number of people being locked out of employment by showing that the long term unemployment rate (unemployment lasting for 27 weeks or longer) is back at pre-crisis levels (although 0.8% is still a lot of people to employed for over 6 months at a time).

Furthermore, while there may be increased inequality, there are still considerable numbers of people that end up in different income quintiles to those that they grew up in (see figure 16). The ability to move up (and also down) different quintiles demonstrates meritocracy.

While Strain says that he does not like the thought of more people falling down the scale, his argument that the American Dream ‘is the possibility - not the certainty - of going from rags to riches’, as well as potential costs, such as what this would mean for returns on investment, make a better case for why pursuing perfect mobility may not be a great idea.

What also helps is the inclusion of two chapters, one written by a progressive and the other an economic populist, arguing against Strain’s hypothesis.

Conservative Populist, Henry Olsen focuses on how participation rates in the labour force among males is down 8% since 1960, as well as real wage stagnation for the bottom two deciles during mid 2000s. He links the shifts in these statistics to China’s accession to the WTO in 2001.

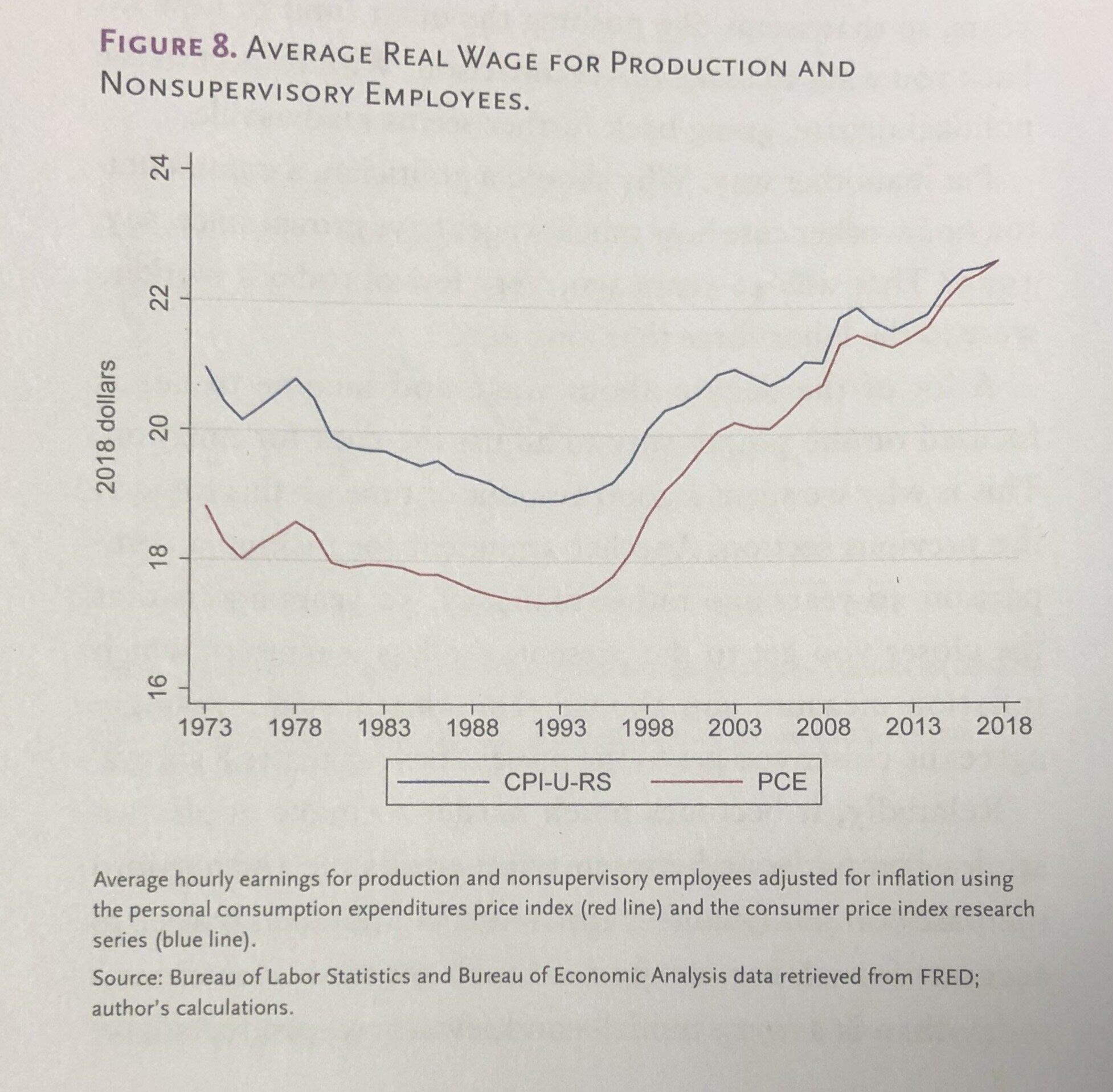

Meanwhile, Eugene Dionne writes that Strain misrepresents Progressives as Luddites while they are in fact suggesting ‘that the fruits of this transformation should be distributed equitably, and that the bargaining power of Americans’ negatively affected by it should be enhanced.’ He also argues that since the 1970s, ‘the hourly inflation adjusted wages received by the typical workers have barely risen, growing only 0.2 percent per year’ which works out as an approximate 10% real increase.

It’s this statistic compared with much of those contained within Strain’s argument which highlights the importance of using the difference inflation measures (PCE vs CPI). Strain argues that ‘a major advantage of the PCE is its more realistic treatment of how consumers respond to price changes’ compared to the CPI which Dionne uses. As seen below, these two measures can yield considerably different conclusions and while both may be cherry picking, the discussion on which measure is right is too large for this post.

In simple terms, it would not be far off to claim that much of Strain’s argument relies upon the accuracy of PCE over CPI. In spite of this, the choice of using 1990 rather than 1970, which Dionne criticises him for, does seem justified. It would not seem sensible to allow those 20 years to distort the three decades of volatile, yet still reasonable, wage growth that have happened since.

Strain concludes by saying that although many may have been left out and require support, we should not forget that the current capitalist model has delivered prosperity for the considerable majority of Americans. ‘We do need a stronger dose of ... stronger incentives in public policy to work and invest, more risk-taking, more basic research, more energy and dynamism.’

However, he admits that America needs a ‘strong safety net’ and also to address ‘deaths of despair’ and loneliness. However, he writes that the conversation of the latter needs to be more considered; ‘perhaps it is simply more enjoyable to order takeout and watch Netflix with your spouse than to go to dinner and a movie with friends. And if so, what’s the problem?’

The deliberate timing of Strain’s book makes it an important one for this US election. With Joe Biden likely to become the Democratic nominee he will be trying to make the case for the economic record of the administration of which he was Vice President. What may be more interesting, however, is how this will inform the debate within the GOP as they begin to contemplate which direction to take after Trump: loyalty to free-market principle or further down the route of conservative populism?