NIT or UBI, that is the (economic) question

The Negative Income Tax (NIT) and the Universal Basic Income (UBI) schemes are often mistakenly interpreted as the two sides of the same coin. This is mainly because both policies aim at tackling poverty through redistributive taxation. However, both from an economic and ethical standpoint, these two policies present differences that should not be disregarded.

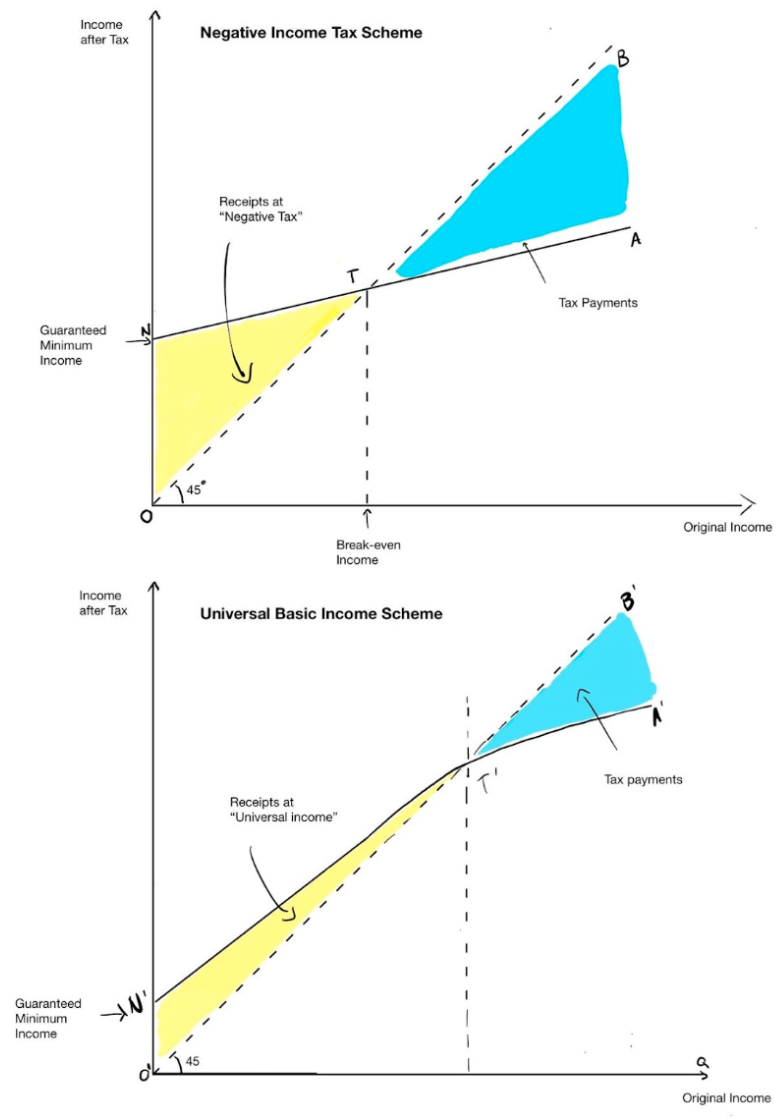

Economically, a NIT can be understood as a tax system associated with a tax deduction, as it proposes a scheme where at the “break-even” level of income, households pay no income tax. Above this level, households pay tax at a constantly increasing marginal rate on each additional pound while, below this level, they receive a payment of such rate at an inverse ratio. In the case of NIT, we can therefore observe a tax transfer (represented by the area NTO in Figure 1) that diminishes as income increases at a rate of -t and becomes zero when an individual’s income reaches the threshold T. Once income surpasses this threshold, taxpayers begin to pay a positive tax, quantified by the area TAB.

On the other hand, the UBI scheme entails the regular distribution of a uniform cash payment to individuals, irrespective of age, without any conditions attached. Realistically, a millionaire will receive the same payout as those currently on Universal Credit. Hence, in the case of UBI, the implementation of a universal and unconditional transfer ON’ to all individuals causes a permanent shift along the 45° line. Following the redistribution, individuals with a gross income below OT’ receive a positive benefit resulting from the disparity between the sum of UBI (represented by ON’) and the taxes paid, measured by the vertical gap between the translated 45° line and the income paid by the firm. Conversely, taxpayers with an income exceeding OT’ will incur a net tax payment.

Figure 1: Economic assessment of NIT and UBI

To ensure that the total benefits provided by a NIT and UBI program are equivalent, the area ONT in the NIT scheme must equal the area ONT’ in the UBI scheme, considering a normal distribution of individuals.

As clearly evident in Figure 1, a NIT scheme benefits individuals with low pre-tax income, but beyond the threshold T, it disadvantages individuals who would receive a higher disposable income under the UBI option. By ensuring equal net costs for both schemes, in a NIT scheme, a minority of poor individuals is therefore supported by middle and high-income taxpayers whereas, in a UBI one, wealthier individuals contribute to redistributing income to middle and low-income individuals. A NIT program has therefore a more pronounced impact on reducing labour supply among low-income earners compared to UBI. From a distributive perspective, NIT exhibits greater effectiveness in combating poverty, but the presence of high marginal tax rates on low incomes might discourage the same individuals to work. Conversely, in the case of UBI, the lower benefits for impoverished individuals, coupled with lower marginal tax rates, incentivize greater participation of low-income individuals in the labour market at the cost of a lower effectiveness in tackling poverty.