What joy, it's Marianna Mazzucato again

This time she's running a conference telling us all how it's absolutely vital that the UK economy be planned the way that Ms. Mazzucato thinks it ought to be. Which is, if we are fair about it, a plan that rather ignores one of the most basic economic points about economies:

This is encouraging news and shows that the UK is hopefully on the path towards ‘rebalancing’ away from an economy biased towards financial services, towards growth of innovation and productivity in the ‘real economy’.

Hmm. For this to be either true or desirable we'd need to show that we actually have an economy biased towards financial services.

The key problem that he and other international policy makers have is to make sure that such rebalancing tackles finance on two equally important sides. On the one hand, rebalancing so that finance funds the real economy. This means addressing the dire situation that figure 1 shows below, i.e. the degree to which finance has been financing itself leading to the exponential rise in the value added made up of financial intermediation, compared to that of the real economy (everything but finance and agriculture).

Hmm, so, OK, finance has been a greater part of the value added in the economy in recent times. It's still difficult to understand why this is a bad idea.

The second key issue that rebalancing must address is not just how to get more value added from the ‘real economy’ and less from ‘financial intermediation’ (finance financing finance), but also how to de-financialise the real economy itself!

Hmm again.

So, back to this question of whether the UK economy is in fact excessively financialised. And there's two parts to that question. In the general economy we're no more financialised than other advanced economies. We have roughly the same sized pensions industry, insurance and retail and commercial banking industries, mortgages, savings products and all the rest. And we need only invoke Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs to see why a richer nation might want more of such financial activity. Once the basic needs are met we move on to wanting to have security which is exactly what savings and insurance do for us.

But it is also true that the total financial sector in the UK is larger than it is in most other countries. Almost nowhere else has anything even remotely comparable to The City. but to say that is a problem would be to make the poor departed spirit of David Ricardo cry. For we do seem to have a comparative advantage in being the financial marketplace for the world and that's an advantage that we should be exploiting.

So if we look at the domestic economy we don't seem to be excessively financialised. And if we look at the total economy that financialisation is about our successfully selling services to Johnny Foreigner. Neither of which are obviously problems that require solutions. Making Ms. Mazzucato's conference, and possibly the good professor herself, somewhat redundant.

Mariana Mazzucato's extremely strange economics

Mariana Mazzucato's got another installment of her rather strange economics in the paper. This is the follow on from the insistence that government funds all innovation. Here's she's decrying the rise of "finance" and how it doesn't actually develop the economy and thus, well, and thus politicians should do it all for us I think. One interesting little thought is that she doesn't seem to have understood Piketty:

Indeed, the origins of the financial crisis and the massive and disproportionate growth of the financial sector originated in the 1970s, as finance became increasingly de-linked from the real economy.

It's also true that Piketty doesn't really understand his own data either. Yes, there has been a rise in the wealth to GDP ratio and yes, it did start in the 70s. For the US and UK this was a rise of about 150% of GDP. And yes, this has almost all been in financial assets. So we can indeed say that finance has risen in importance as a part of the economy.

But what has also happened is that pensions savings have risen by 150% of GDP over this same time period. That is, that the rise of finance seems very closely correlated with the baby boomers saving for their retirements.

It's difficult to see this as a problem really.

Then there's this entirely bizarre point she makes:

In the attempt to "rebalance" economies away from speculative finance towards the real economy, there have been proposals to reform finance so that it helps to fuel more innovation. Various measures have been tried to help those few small and medium enterprises willing to go after difficult high-risk investments, the backbone of innovation. Yet these reforms have been inadequate, slow and incomplete, with the proportion of profits from quick trades in the financial sector, rather than long-run investments, rising not falling. And one of the key tools for long-termism, the financial transaction tax, has still not been applied.

She seems not to have read the EU's own report on the FTT (which I wrote about here). The EU itself states that the introduction of an FTT will reduce investment in business, so much so that the economy will actually shrink compared to where it would be without the FTT. So Mazzucato is apparently recommending a course of action, in order to increase investment, which we know will actually reduce investment.

It's an odd policy world she inhabits, isn't it?

The rest of it is just that we should have a Public Investment Bank and everything will be sweet. Which, given the things that politicians like to invest in (Olympics, HS2, Concorde, write your own list) is a very sweet but most misguided hope.

Rising demand hits static supply: what shall we do?

So here's a little puzzler. Imagine that we had some good or service that was in limited supply. And that then demand for that good or service rose. What could or should we do to deal with this problem? For obviously some of those who desire that good or service are going to be disappointed given that we cannot increase supply. The obvious logical answer is that we should increase the price of that good or service. This will, in the way that rising prices tend to do, reduce demand for that good or service. Further, we also know that that limited supply will go to those who value it the most: we working this out by concluding that those willing to pay a higher price are those who do value something more highly.

Then we get the Mail:

What a rip off! Hotel room prices in Glasgow soar 158 PER CENT to up to £448 a night as city prepares to host Commonwealth Games

A night in a hotel will now cost an average of £344 for the Games period A year ago prices were on average of £78 per room The most expensive night - Sunday 27 July - will cost an average of £448

That's the house magazine of the angrier part of Middle England complaining about the solution to that difficult problem that, well, when a sporting event is going on more people want to stay in a city which has, in the short term at least, a static supply of hotel rooms.

No wonder we all have problems getting economically rational political policies put in place, eh?

Should central banks do emergency lending?

A barnstorming new paper from the Richmond Fed, written by its President Jeffrey Lacker and staff economist Renee Haltom, argues that the Federal Reserve has drifted into doing too much credit policy to the detriment of its traditional goal of overall macroeconomic stabilisation.

In its 100-year history, many of the Federal Reserve’s actions in the nameof financial stability have come through emergency lending once financial crises are underway. It is not obvious that the Fed should be involved in emergency lending, however, since expectations of such lending can increase the likelihood of crises. Arguments in favor of this role often misread history. Instead, history and experience suggest that the Fed’s balance sheet activities should be restricted to the conduct of monetary policy.

The first step in their case is attacking the idea that the Fed was created to be a lender to specific troubled institutions or sectors:

Congress created the Fed to “furnish an elastic currency.”...In other words, the Fed was created to achieve what can be best described as monetary stability. The Fed was designed to smoothly accommodate swings in currency demand, thereby dampening seasonal interest rate movements. The Fed’s design also was intended to eliminate bank panics by assuring the public that solvent banks would be able to satisfy mass requests to convert one monetary instrument (deposits) into another (currency). Preventing bank panics would solve a monetary instability problem.The Fed’s original monetary function is distinct from credit allocation, which is when policymakers choose certain firms or markets to receive credit over others.

They go on to explain further the difference between monetary policy (providing overall nominal stability; making sure that shocks to money demand do not lead to macroeconomic instability & recessions) and credit policy (choosing specific firms to receive support and funds—effectively a form of microeconomic central planning):

Monetary policy consists of the central bank’s actions that expand or contract its monetary liabilities. By contrast, a central bank’s actions constitute credit policy if they alter the composition of its portfolio—by lending, for example—without affecting the outstanding amount of monetary liabilities. To be sure, lending directly to a firm can accomplish both. But in the Fed’s modern monetary policy procedures, the banking system reserves that result from Fed lending are automatically drained through off setting open market operations to avoid driving the federal funds rate below target.

The lending is, thus, effec-tively “sterilized,” and the Fed can be thought of as selling Treasury securities and lending the proceeds to the borrower, an action that is functionally equivalent to fiscal policy.

They go on to explain why Walter Bagehot provides "scant support" for the creditist approach to crisis management, while the facts of the Great Depression do not fit with the creditist story.

Finally, they note that even if there are inherent instabilities in the financial system—something far from proven—many of these are made substantially worse by central bank intervention in credit markets.

Financial institutions don’t have to fund themselves with short-term, demand-able debt. If they choose to, they can include provisions to make contracts more resilient, reducing the incentive for runs. Many of these safeguards already exist: contracts often include limits on risk-taking, liquidity requirements, overcollateralization, and other mechanisms.

Moreover, contractual provisions can explicitly limit investors’ abilities to flee suddenly, for example, by requiring advance notice of withdrawals or allowing borrowers to restrict investor liquidations. Indeed, many financial entities outside the banking sector, such as hedge funds, avoided financial stress by adopting such measures prior to the crisis.Yet, leading up to the crisis, many financial institutions chose funding structures that left them vulnerable to sudden mass withdrawals. Why?

Arguably, precedents established by the government convinced market participants of an implicit government commitment to provide backstop liquidity. Since the 1970s, the government has rescued increasingly large fi nancial institutions and markets in distress. This encourages large, interconnected fi nancial fi rms to take greater risks, including the choice of more fragile and often more profi table funding structures. For example, larger financial firms relied to a greater extent on the short-term credit markets that ended up receiving government support during the crisis. This is the well-known “too big to fail” problem.

I apologise for the length of the quotation, but the paper really is excellent. Do read the whole thing.

Why we're very much richer than the GDP numbers tell us we are

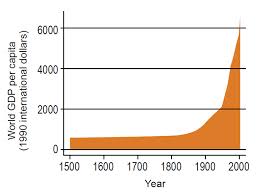

We're continually told that GDP isn't actually all that good at measuring how well off we really are. It doesn't measure the costs of pollution, it covers only market activity, it doesn't look at the distribution of wealth or income and so on. All of those things are true. But it's also true that GDP measures grossly underestimate how well of we all are collectively as well. The reason is contained in that chart above. Because GDP is only measuring matters at that equilibrium price.

That means that the producer surplus, the profits, gross margins, what have you, are included in GDP. But that consumer surplus is not.

An example of what is meant here. Your humble author lives in rural Portugal where the mains water supply comes from the City. The pricing system is sensible, possibly even rational, for a drought prone area. There's a low and fixed cost, some €20 a month, for a basic water supply. This covers the usuals for the average household, drinking, washing, cleaning, bathing, but no more. If you want to use more water, say to fill a pool, one must pay extra. And one pays more per unit of water the more one uses. Try to irrigate a substantial garden and that will costs hundreds of euros a month (and we certainly check for leaks now given that a jammed toilet cistern led to a €300 bill).

However, what are we really prepared to pay for water? We've lived in places where the tap water was not, at least not to those immune to various bugs, actually potable. At such times we were absolutely delighted to pay, say, €1 a litre for the 4 litres a day that a couple of adults might get through. Bathing water from the tap but drinking water from the bottle.

So we'd be perfectly happy, if no other method were available, to pay €120 a month for just our drinking water. Well, perhaps not happy, but we'd do it: and the important thing here is that we're now being charged €20 and getting all our bathing, washing etc water for free.

We have a consumer surplus of €100 a month,at least, something that is vastly greater than the €20 a month that is recorded in the GDP figures, and that €100 isn't appearing anywhere at all in the national accounts. As far as the usual measures of wealth and or income, even of living standards, we're just not noting that number at all.

It's very difficult to actually prove this following statement because no one can accurately measure that consumer surplus. The amount that people would be willing to pay if they had to but which they do not because of that equilibrium price. For if it could be worked out accurately, and who would pay the extra would be, then firms would be doing their darndest to charge those different amounts and thus turn the consumer surplus into producer surplus. In rather the manner that VW sells essentially the same car under the Skoda, VW, Audi, Porsche and even Bentley brands. Tart it up, slap a different badge on it and see if you can get someone to pay more for it: product differentiation to attempt to capture some of that consumer surplus. But it's arguable that that consumer surplus is, across the economy, many times the actual recorded GDP, as it is in the worked out example of water supply.

One more point about the very modern world. We're getting a lot of things for free these days, things that we used to have to pay for. That equilibrium price, that market price, is therefore falling, so therefore so is the contribution to GDP of those things that are becoming free. Music streaming, messaging, information search and so on. But the consumer surplus of these things is just as vast, if not perhaps greater, than that water example.

So yes, GDP isn't a very good method of judging how well off we are. For we've now got the absurd fact that as the consumer surplus grows with free things, we're actually recording lower GDP at the same time. We're all getting richer but the numbers say we're getting poorer.

On the appallingness of traditional English food

We're all well aware of the appalling nature of the traditional English cuisine. Oddly preserved vegetables (mushy peas?), grossly overcooked fresh ones, allied with dubious meat masked with gelatinous sauces. At least one American professor insists that the real reason for the British Empire was the desperate search for a decent lunch. That we found that lunch, as modern day English cuisine shows, is therefore why we gave up that empire, job done as it were. Paul Krugman has written on this point:

Maybe the first question is how English cooking got to be so bad in the first place. A good guess is that the country’s early industrialization and urbanization was the culprit. Millions of people moved rapidly off the land and away from access to traditional ingredients. Worse, they did so at a time when the technology of urban food supply was still primitive: Victorian London already had well over a million people, but most of its food came in by horse- drawn barge. And so ordinary people, and even the middle classes, were forced into a cuisine based on canned goods (mushy peas!), preserved meats (hence those pies), and root vegetables that didn’t need refrigeration (e.g. potatoes, which explain the chips). But why did the food stay so bad after refrigerated railroad cars and ships, frozen foods (better than canned, anyway), and eventually air-freight deliveries of fresh fish and vegetables had become available? Now we’re talking about economics–and about the limits of conventional economic theory. For the answer is surely that by the time it became possible for urban Britons to eat decently, they no longer knew the difference. The appreciation of good food is, quite literally, an acquired taste–but because your typical Englishman, circa, say, 1975, had never had a really good meal, he didn’t demand one. And because consumers didn’t demand good food, they didn’t get it. Even then there were surely some people who would have liked better, just not enough to provide a critical mass.

There's possibly a certain tongue in cheek element there but a great deal of truth as well.

However, there's one little point coming out of an economic history project looking at the First World War that throws an interesting light on all of this. They have been taking a detailed look at the heights of those who joined the Army after 1914. Did birth order affect height? Economic background? Crowded industrial area as origin? All those sorts of things and then we get this:

Nor do we find that living in an agricultural district confers much height advantage, as studies of much earlier eras have found, probably because market integration had diminished the benefit of living close to food sources.

Something that is most, most, interesting.

If the tasteless nosh produced by those canning and early preservation techniques had been less healthy (rather than just less appetising) than fresh grown country food then we would have expected to see some differential in height between rural and urban entrants into the Army. But we don't: differences in height are explained by many other factors but not by that access to fresh food or preserved.

Krugman may be right that that early urbanisation and the crude techniques used to preserve the necessary food led to the destruction of the palates of the nation for several generations. But while it may have led to a cuisine that would have (and did in some instances) make a Frenchman projectile vomit, there's not really any evidence that it was an unhealthy diet. At least, not compared to what they were still eating out in the countryside.

Brown Windsor soup, corned beef pie with two overboiled veg, spotted dick to follow anyone?

So just what is slow economic growth then?

This is slightly worrying:

Just how difficult this has become was shown last week when the OECD released its predictions for the world economy until 2060. These are that growth will slow to around two-thirds its current rate; that inequality will increase massively; and that there is a big risk that climate change will make things worse. Despite all this, says the OECD, the world will be four times richer, more productive, more globalised and more highly educated. If you are struggling to rationalise the two halves of that prediction then don't worry – so are some of the best-qualified economists on earth.

World growth will slow to 2.7%, says the Paris-based thinktank, because the catch-up effects boosting growth in the developing world – population growth, education, urbanisation – will peter out. Even before that happens, near-stagnation in advanced economies means a long-term global average over the next 50 years of just 3% growth, which is low. The growth of high-skilled jobs and the automation of medium-skilled jobs means, on the central projection, that inequality will rise by 30%.

Not the predictions themselves, which come from this OECD report, but the interpretation that is put upon them. For it appears that Paul Mason, supposedly one of those employed to explain the world to us, is incapable of actually reading a report.

On the inequality point he's missed the crucial qualifier: "in-country" inequality. The report is actually telling us that the currently poor countries are going to catch up with the currently rich ones and that when they do, when they join us at the technological frontier, then their growth will be lower than it is during the current catch up phase.

That is, the prediction is that the vast gulfs of inequality between those living on a $1 a day and ourselves will be closed: yet Mason is concerning himself with that trivial 30% rise in inequality amongst ourselves, the already rich. It's absurd to be worrying that in-country gini will rise from, say, 0.30 to 0.39 while not celebrating the collapse of the global gini from 0.80 to 0.40 (made up numbers just for illustration). At least it's absurd if inequality is one of those things that you want to worry about.

There's another misunderstanding there, one which anyone who has actually read Piketty should understand for he explains it very well. Gross GDP growth, the size of the entire economy, is driven by two different things. One is the expansion of the population that is producing that GDP. The other is the efficiency with which each person is contributing to that GDP. The report is stating that the entire globe is just about to finish going through the demographic transition, as the UN and everyone else assumes it is. Thus population growth will not be contributing to growth after some few decades of the future.

3% (or 2.7%) growth without the demographic effect is not low or slow growth: this is fast growth. The economy doubles every 25 years or so but over the same number of people meaning that per capita GDP doubles every 25 years. This is not an historically slow level of per capita GDP growth. This is actually rather fast.

It's not the specific predictions that worry at all: it's that someone supposedly employed to explain such matters to us doesn't seem to understand the points being made. How did we end up in this situation?

One of the upsides of having a global elite is that at least they know what's going on. We, the deluded masses, may have to wait for decades to find out who the paedophiles in high places are; and which banks are criminal, or bust. But the elite are supposed to know in real time – and on that basis to make accurate predictions.

Well, yes, quite.

Voxplainer on Scott Sumner & market monetarism

I have to admit that I usually dislike Vox. The twitter parody account Vaux News gets it kinda right in my opinion—they manage to turn anything into a centre-left talking point—and from the very beginning traded on their supposedly neutral image to write unbelievably loaded "explainer" articles in many areas. They have also written complete nonsense. But they have some really smart and talented authors, and one of those is Timothy B. Lee, who has just written an explainer of all things market monetarism, Prof. Scott Sumner, and nominal GDP targeting. Blog readers may remember that only a few weeks ago Scott gave a barnstorming Adam Smith Lecture (see it on youtube here). Readers may also know that I am rather obsessed with this particular issue myself.*

So I'm extremely happy to say that the article is great. Some excerpts:

Market monetarism builds on monetarism, a school of thought that emerged in the 20th century. Its most famous advocate was Nobel prize winner Milton Friedman. Market monetarists and classic monetarists agree that monetary policy is extremely powerful. Friedman famously argued that excessively tight monetary policy caused the Great Depression. Sumner makes the same argument about the Great Recession. Market monetarists have borrowed many monetarist ideas and see themselves as heirs to the monetarist tradition.

But Sumner placed a much greater emphasis than Friedman on the importance of market expectations — the "market" part of market monetarism. Friedman thought central banks should expand the money supply at a pre-determined rate and do little else. In contrast, Sumner and other market monetarists argue that the Fed should set a target for long-term growth of national output and commit to do whatever it takes to keep the economy on that trajectory. In Sumner's view, what a central bank says about its future actions is just as important as what it does.

And:

In 2011, the concept of nominal GDP targeting attracted a wave of influential endorsements:

Michael Woodford, a widely respected monetary economist who wrote a leading monetary economics textbook, endorsed NGDP targeting at a monetary policy conference in September.

The next month, Christina Romer wrote a New York Times op-ed calling for the Fed to "begin targeting the path of nominal gross domestic product." Romer is widely respected in the economics profession and chaired President Obama's Council of Economic Advisors during the first two years of his administration.

Also in October, Jan Hatzius, the chief economist of Goldman Sachs, endorsed NGDP targeting. He wrote that the effectiveness of the policy "depends critically on the credibility of the Fed's commitment" — a key part of Sumner's argument.

But read the whole thing, as they say.

*[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16]

An unpublished letter to the LRB on high frequency trading

Lanchester, John. "Scalpers Inc." Review of Flash Boys: Cracking the Money Code, by Michael Lewis. London Review of Books 36 no. 11 (2014): 7-9, http://www.lrb.co.uk/v36/n11/john-lanchester/scalpers-inc Dear Sir,

It is striking for John Lanchester to claim that those who believe high-frequency trading is a net benefit to finance (and by extension, society) "offer no data to support" their views. Aside from the fact that he presents such views in the line of climate-change deniers, rather than a perfectly respectable mainstream view in financial economics, it doesn't really seem like he has gone out looking for any data himself!

In fact there is a wide literature on the costs and benefits of HFT, much of it very recent. While Lanchester (apparently following Lewis) dismisses the claim that HFT provides liquidity as essentially apologia, a 2014 paper in The Financial Review finds that "HFT continuously provides liquidity in most situations" and "resolves temporal imbalances in order flow by providing liquidity where the public supply is insufficient, and provide a valuable service during periods of market uncertainty". [1]

And looking more broadly, a widely-cited 2013 review paper, which looks at studies that isolate and analyse the impacts of adding more HFT to markets, found that "virtually every time a market structure change results in more HFT, liquidity and market quality have improved because liquidity suppliers are better able to adjust their quotes in response to new information." [2]

There is nary a mention of price discovery in Lanchester's piece—yet economists consider this basically the whole point of markets. And many high quality studies, including a 2013 European Central Bank paper [3], find that "HFTs facilitate price efficiency by trading in the direction of permanent price changes and in the opposite direction of transitory pricing errors, both on average and on the highest volatility days".

Of course, we should all know that HFT narrows spreads. For example, a 2013 paper found that the introduction of an algorithmic-trade-limiting regulation in Canada in April 2012 drove the bid-ask spread up by 9%. [4] This, the authors say, mainly harms retail investors.

The evidence is out there, and easy to find—but not always easy to fit into the narrative of a financial thriller.

Ben Southwood London

[1] http://student.bus.olemiss.edu/files/VanNessR/Financial%20Review/Issues/May%202014%20special%20issue/Jarnecic/HFT-LSE-liquidity-provision-2014-01-09-final.docx [2] http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~jhasbrou/Teaching/2014%20Winter%20Markets/Readings/HFT0324.pdf [3] http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1602.pdf [4] http://qed.econ.queensu.ca/pub/faculty/milne/322/IIROC_FeeChange_submission_KM_AP3.pdf

Danny Dorling tells us what inequality is really all about

I've been lucky enough to get a copy in proof of the next Danny Dorling book, "Inequality and the 1%". And I've got to tell you it's a corker, although perhaps not for the reasons that Professor Dorling might hope. For example, he tells us in the first chapter what inequality is really all about. No, it isn't, as you might have thought, that the rich and poor are moving ever further apart and that this is, in some manner, a bad thing. No, he's quite insistent that it's really about the growing gap between the 1% and the other 9% of the top 10%.

The bankers and the CEOs have seen their incomes soar above what can be earned by other members of the upper middle classes like, oooh, say, senior journalists at The Guardian, Oxbridge professors and the like. And this is a very bad thing indeed and something must be done. Because those ghastly people in trade are now able to monopolise all of the positional goods d'ye see?

A couple of generations ago nice houses in London, the Georgian rectory in the countryside, these could be afforded by many of the professional classes. Now they're only available to those who decided to do commerce and won't somebody think of the poor intellectuals trailing in their wake?

That is, the entire current concern about inequality is a massive whingefest by those who look down upon their intellectual inferiors but find that they then get outbid by them them for the finer things in life.

It's clearly rich in comic possibilities to take this argument seriously. So perhaps we should take this argument seriously so that we can make fun of it. The major problem with Britain today is that Guardian journalists cannot buy nice houses in Islington. Discuss.