Companies are the cells of the economy

An interesting point being made by Ronald Coase here:

Wang: Microeconomics is about demand and supply. Compared with classical economics, marginal analysis clearly offers a deeper understanding of consumer choice. But I don’t think it is equally powerful in explicating production, the supply side of the economy.Coase: To understand production, we have to go back to Adam Smith’s division of labor. It serves well as a starting point, even though the modern economy today has become far more complicated.

Wang: This must be Smith’s most undeserving failure. Modern economics is built on Smith’s framework of the “invisible hand”. But it leaves no room for the division of labor.

Coase: Modern economics shows little interest in production. I am not sure production function tells us anything about production in the economy.

Wang: Adam Smith used the pin factory as an example to develop his analysis of the division of labor. Today, to investigate the division of labor, we can no longer afford to confine our focus to a single firm. Instead, we have to study the organizational structure of production.

Coase: That’s right. The firm remains the cell of the economy, but the intricate relations and constant interactions among the cells determine economic dynamism.

It's that last line that so particularly interests me. For it's often pointed out that companies are little sections of a command economy and thus, some leap to say, obviously it's possible to have a command economy because we actually do.

It's possible however to run Coase's analogy in two ways. One is to make that distinction between the cell itself and the entire organism, which do run to different rules. Another might be to compare it to physics: we know very well that there are entirely different rules at the quantum level and at the macro.

Any such analogy can be pushed too far of course but with the economy that cell might well be subject to central planning: but it's the interaction of all of those limited plans which leads to the vibrancy of the economy as a whole. We as entire human beings cannot and do not work by the same rules that apply at the cellular level: nor do economies work well subject to the same rules that might apply at the company or organisational level.

A simple point on railway nationalisation

One point people bring up when they advocate renationalising railways (or renationalising stuff in general) is that when private companies run something they take a chunk of the total surplus in profit, but if the government were in control, that could go to them. But there's a very basic reason why this isn't the case: opportunity cost. A firm, in doing business, puts capital to use. It uses a mix of physical and human capital and devotes it toward achieving tasks in order, usually, to turn a profit.

The best way to measure the amount of capital tied up in a project is the market's assessment thereof—the firm's market capitalisation—although of course we know that market prices are never perfectly accurate, since they are only on their way to an ever-changing equilibrium, and they may not have got there yet. And what's more, not all the relevant information will always be in the public domain.

For rail franchises—or TOCs (Train Operating Companies), as they seem to call themselves—it is relatively hard to pinpoint the exact amount of capital they are using, as they are usually subdivisions of a larger structure. But suffice to say, running trains involves tying up money on the order of billions, whoever does it (i.e. it includes Directly Operated Railways, the state body that is currently running the East Coast Mainline pretty well). You have to rent the rolling stock (trains), pay the staff, buy the fuel, pay to use the track and so on.

From this capital you get a return. TOC margins average about 4% over the last ten years. The average company got more like 10%. FTSE100 companies seem to enjoy higher returns. Of course, operating profits are not share returns, but they tell more or less the same story. The extra couple dozen billion the government would need to spend on trains could equally be spent on equities or anywhere else for more or less the same risk-adjusted return. The return they got here could be put into trains.

But even doing this makes no sense. If the government returns that couple dozen billion to the population at large, the government can tax the income that the private citizens make on the wealth, at a glance dealing with the problems of governments holding wealth—principally: they are not very good at picking winners. Or they could pay off debt and reduce their repayment costs—since the risk-adjusted return of gilts is priced in just the same way as other assets.

Either way, and whether or not rail re-nationalisation makes sense from any other perspective, it is simply not the case that government, by nationalising rail, could get a bit of extra cash to put into our network.

What glories this capitalist free market thing hath wrought

There's nothing worse than being exploited by some running lackey pig dog of a capitalist, as Deirdre McCloskey reminds us:

The aim of the true Liberal should not be equality but “lifting up those below him.” It is to be achieved not by redistribution but by free trade and compulsory education and women’s rights.And it came to pass. In the UK since 1800, or Italy since 1900, or Hong Kong since 1950, real income per head has increased by a factor of anywhere from 15 to 100, depending on how one allows for the improved quality of steel girders and plate glass, medicine and economics.

In relative terms, the poorest people in the developed economies and billions in the poor countries have been the biggest beneficiaries. The rich became richer, true. But the poor have gas heating, cars, smallpox vaccinations, indoor plumbing, cheap travel, rights for women, low child mortality, adequate nutrition, taller bodies, doubled life expectancy, schooling for their kids, newspapers, a vote, a shot at university and respect.

Never had anything similar happened, not in the glory of Greece or the grandeur of Rome, not in ancient Egypt or medieval China. What I call The Great Enrichment is the main fact and finding of economic history.

It's that penultimate sentence which is so important. There have most certainly been many attempts at designing economic systems: there have been even more that just sorta happened out of voluntary interactions. But there's only one of them that has actually managed what we are all the lucky, lucky, beneficiaries of. That is, one economic method of organisation that has led to a substantial, sustained, increase in the standard of living of the average woman on the Clapham Omnibus.

Nothing else, nothing planned nor nothing unplanned, has managed this. And that really is the main fact and finding of economic history. It's the one unique even in it too. McCloskey, you and I, we might differ on the details of how it all happened but we shouldn't allow minor disagreements over precedence between the flea and the louse to obscure the manner in which we're all feeding off that larger truth. That nothing else does work as well as those largely bourgeois virtues plus economic and social liberty.

What would we consider a successful railway system?

Under many measures, the railways have performed remarkably since privatisation. It is not surprising that the British public would nevertheless like to renationalise them, given how ignorant we know they are, but it's at least slightly surprising that large sections of the intelligentsia seem to agree.

Last year I wrote a very short piece on the issue, pointing out the basic facts: the UK has had two eras of private railways, both extremely successful, and a long period of extremely unsuccessful state control. Franchising probably isn't the ideal way of running the rail system privately, but it seems like even a relatively bad private system outperforms the state.

Short history: approximately free market in rail until 1913, built mainly with private capital. Government control/direction during the war. Government decides the railways aren't making enough profit in 1923 and reorganises them into bigger regional monopolies. These aren't very successful (in a very difficult macro environment) so it nationalises them—along with everything else—in the late 1940s.

By the 1960s the government runs railways into the ground to the point it essentially needs to destroy or mothball half the network. Government re-privatises the railways in 1995—at this point passenger journeys have reached half the level they were at in 1913. Within 15 years they've made back the ground lost in the previous eighty.

But maybe it's not privatisation that led to this growth. Let's consider some alternative hypotheses:

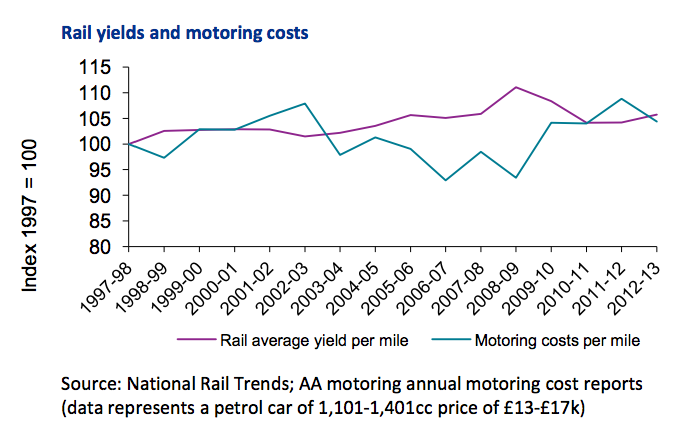

Was it a big rise in the cost of driving?

Was it the big rise in GDP over the period that did it?

Was it just something that was happening around the developed world?

Was it purely down to extra cash injections from the state?

Has it come at the expense of safety?

Has it come at the expense of customer satisfaction?

Has it come at the expense of freight?

Is it all driven by London?

An infrastructure push does not lead to a boost to GDP

We've heard much these past few years about how now id just the time to have an infrastructure surge. It's said often enough that a recession is just when we should be building all those roads, railways, council houses and the rest. Obama even tried to find those $800 billion worth of shovel ready projects just raring to do. With no great success it should be said. Sadly, this just doesn't seem to work. From the IMF:

This paper has examined whether major public investment drives in the past have served to promote or accelerate national economic growth. It is not about whether in theory public investment drives could accelerate growth, but rather whether in practice, with real governments deciding how to spend the funds and implementing investments, they have in fact accelerated growth.

The answer appears to be “probably very little”. This conclusion pertains to the drives – the big increases in public capital spending – not necessarily to routine levels of public investment. And furthermore the evidence here is not about whether public capital can promote growth by averting the emergence of bottlenecks. Major public investment campaigns continue to be advocated in several countries as a major trigger for economic growth, and on this issue, whether they have in fact triggered growth, the evidence for a positive effect of public capital on GDP or GDP growth is weak. … It is difficult to find a clear-cut example that fits the oft-repeated narrative of a public investment boom followed by acceleration in GDP growth. If anything the cases of clear-cut booms illustrate the opposite – major drives in the past have been followed by slumps rather than booms.

In theory it should work, in practice it doesn't, which is a bit of a conundrum. The practical answer to which puzzle is that government is probably even worse at doing things than we generally think. Thus we'd probably be better off limiting it to that very small set of things that both must be done and that only government can do. Something which is a very small overlap indeed.

Boris's BOGOF

Boris Johnson’s putative return to the Commons overwhelmed any publicity for his, or rather Gerard Lyons’s, strategic analysis of the UK’s in/out EU options: The Europe Report: A Win-Win Situation, released 6th August. Four possible outcomes are envisaged: staying in either a largely unreformed EU or one reformed to the UK’s liking. The two departure options are seen as (a) good EU relations and pro-growth UK reforms and (b) poor EU relations and an inward-looking UK. Lyons makes the good point that “the UK can only achieve serious reform if it is serious about leaving, and it can only be serious about leaving if it believed that is better than an unreformed EU.” The title would have you believe both staying in a reformed EU and leaving are “Win Situations” that we can either choose one or use it to achieve the other, i.e. Buy One and Get One Free.

Lyons has produced an important review of the issues facing each sector but, at the end of the day, his conclusions are based on simple assumptions of the economic outcomes from each option. We do not need 108 pages of report, and 130 pages of appendices, to be told that the two high growth scenarios are more attractive than the two low growth ones. Furthermore, the conclusion that the two high growth scenarios are economically equivalent is similarly based on heroic assumptions. Lyons’s Panglossian vision of the UK outside the EU and reforming itself begs a great number of questions. The world is not ordered according to the way we order ourselves: trading with the EU will still be governed by EU regulations, likewise the US.

The paper has a number of failings: in particular it is not specific about the EU and UK reforms that would be needed, still less how they could be achieved and how likely that would be. For example, the only hope of securing the EU reform the UK seeks is for the UK to show benefit for EU as a whole, not just the UK. UK proposals to improve the EU market for financial services looks, to the rest of the EU, like UK self interest. We know that the rest of the EU does not accept the UK arguments because it is outvoted every time.

How would, as Lyons suggests, the UK leave the EU whilst at the same time improving the UK’s EU relationships? The chilling legal issue is EU Article 50 under which the remaining members decide the terms of the separation with no involvement of the departing member. Obviously there would be negotiation so that may not be as ugly as it seems. Trade would continue and we import more from the rest of the EU than we sell them but that is beside the point: could the UK protect its EU exports better than it could reduce its EU imports? De Gaulle reckoned that the UK needed continental Europe more than vice versa and the 1960s proved him right.

We should welcome this report for its discussion of many of the issues but we cannot rely on its findings. The City really does need to come up with a plan to protect its future but this is not it.

They're lying again about the gender pay gap you know

Oh dear, oh dearie me. We find ourselves with a politician trying to feed us all porkies again. This time it's Gloria De Piero announcing loudly that the gender pay gap is near 20% (along with the usual this is disgusting, must stop, Labour will do something about it and so on). She's making the same claim that Harriet Harman did a few years ago: and she seems to have forgotten that the UK Statistics Authority said that Mrs. Dromey was in fact a very naughty politician indeed for making the claim in the manner she did. And as Del Piero is making the same claim in the same manner that also makes Ms. Del Piero a very naughty politician indeed. And we tend to think that it's worth calling out politicians when they attempt to mislead us all by being so naughty.

You can see the actual claims being made all laid out in charts here at the Mail. Full time male employees make more than full time female employees. Part time female employees make more than part time male employees. There are many more female part timers than male: and the average part time wage for either gender is lower than the full time wage for either or both.

And what Del Piero has done to get to her 20% or so figure (the actual numbers coming from the correct source, ASHE) is to include the part time and full time female numbers into one, the part time and full time male numbers into one, and then compare the two. This is not acceptable. As Sir Michael Scholar pointed out to Harriet Harman when she did the same those years ago:

GOVERNMENT EQUALITIES OFFICE PRESS RELEASE: 27 APRIL 2009 I am writing to you about the Government Equalities Office (GEO) Press Release on the Equality Bill, issued on 27 April, which states that women are paid on average 23 per cent less per hour than men. GEO’s headline estimate of the difference between the earnings of women compared with men (generally referred to as the gender pay gap) is some 10 percentage points higher than the 12.8 per cent figure quoted by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Yet both estimates are derived from the same source, the 2008 Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE). Such a difference in headline estimates is likely to confuse the general public. The Statistics Authority is concerned that this may undermine public trust in official statistics. I understand that there has been a dialogue between ONS and GEO on the presentation of women’s earnings figures in the context of Equality issues and that the National Statistician has agreed to look at the way the gender pay gap is presented in ONS statistical bulletins. Work on this is planned for later this year and will be used to inform the content of ONS’s statistical bulletin on the results of the 2009 ASHE, due in November 2009. In the meantime, I enclose a copy of a note that the Statistics Authority will shortly publish on its website. This clarifies why figures as different as 12.8 per cent and 23 per cent have been used and explores different options for presenting the gender pay gap in an impartial and objective way. The note explains that the figure of 23 per cent quoted in the GEO press release relates to the median hourly earnings of all employees (full-time and part-time combined) whereas ONS's figure of 12.8 per cent is based on the difference in the median hourly earnings of full-time employees only. Neither measure is entirely satisfactory as an impartial and objective headline estimate. The former rolls together the quite different levels of hourly earnings for part-time and full-time employees; while the latter excludes the earnings of around one quarter of all employees. These considerations suggest the need for a more extensive set of measures to present the differences between the earnings of men and women. Indeed, it is the Statistics Authority’s view that use of the 23% on its own, without qualification, risks giving a misleading quantification of the gender pay gap. I trust that you will find this note of value pending the further work that ONS is planning on this issue later this year.

That does indeed make Ms. Del Piero a very naught politician indeed and as she does the rounds of the talk and news shows to promote this old Labour mistake perhaps someone would like to pick her up on it?

As to the reality of the gender pay gap it's made up of two things. The first is that there really was, historically, direct discrimination against women in education and career opportunities. That is something almost entirely solved for today's younger generation and we see the effects still only in the older age cohorts, in the inequality of wages of people in their 40s and older. There is no such inequality among the young.

The second is that women tend to take career breaks in order to have and to raise their children in a manner that the fathers of those same children do not. We might rail against that sexist notion that this should be so but it's hardly an unusual gender division of labour in a viviparous, mammalian, species.

The part of the gender pay gap that comes from direct discrimination has already been dealt with, the part that comes from how people decide to live their lives and raise their children, well, that will be with us for as long as that's how people decide that they want to live their lives and raise their children.

And adding together part and full time wages to describe the gender pay gap is a naughty thing to do. As the Statistics Authority has already told one Labour politician when they did it.

A bankers’ ethics oath risks being seen as empty posturing

The suggestion put forward yesterday by ResPublica think-tank that we can restore consumer trust and confidence in the financial system, or prevent the next crisis by requiring bankers to swear an oath seems excessively naïve. Such a pledge trivializes the ethical issues that banks and their employees face in the real world. It gives a false sense of confidence that implies that an expression of a few lines of moral platitudes will equip bankers to resist the temptations of short-term gain and rent-seeking behavior that are present in the financial services industry.

In fairness to ResPublica’s report on “Virtuous Baking” the bankers’ oath is just one of many otherwise quite reasonable proposals to address the moral decay that seems to be prevalent in some sections of the banking industry.

I don’t for a moment suggest that banking, or any other business for that matter, should not be governed by highest moral and ethical standards. Indeed, the ResPublica report is written from Aristotelian ‘virtue theory’ perspective that could be applied as a resource for reforming the culture of the banking industry. ‘Virtue theory’ recognizes that people’s needs are different and virtue in banking would be about meeting the diverse needs of all, not just the needs of the few.

The main contribution of the “Virtuous Banking” report is to bring the concepts of morality and ethical frameworks into public discourse. Such discourse is laudable but we should be under no illusion that changing the culture of the financial services industry will be a long process. Taking an oath will not change an individual’s moral and ethical worldview or behaviour. The only way ethical and moral conduct can be reintroduced back into the banking sector is if the people who work in the industry were to hold themselves intrinsically to the highest ethical and moral standards.

Bankers operate within tight regulatory frameworks; the quickest way to drive behavioural change is therefore through regulatory interventions. However, banking is already the most regulated industry known to man and regulation has not produced any sustainable change in the banks’ conduct. One of the key problems with prevailing regulatory paradigms is that regulation limits managerial choice to reduce risk in the banking system, rather than focuses on regulating the drivers for managerial decision-making.

Market-based regulations that do not punish excellence but incentivize bankers to seriously think through the risk-return implications of their business decisions, will be good for the financial services industry and the economy as a whole. A regulatory approach that makes banks and bankers liable for their decisions and actions through mechanisms such as bonus claw-back clauses will be more effective in reducing moral hazard at the systemic level and improving individual accountability at the micro level than taking a “Hippocratic” bankers’ oath.

A typically wise observation from Don Boudreaux

This is also a rather clever observation. We're told that both wealth and income inequality are rising strongly, that this is of course terrible, and that this leads to rioting in the streets and the stringing up of plutocrats from lamp posts. Yet when we look out our windows we see a distressing lack of the wealth swinging gently in the breeze, all the Occupy folk have gone home to polish their nose rings and there just doesn't seem to be a mass frustration with matters at all. How can this be? When the clerisy tell us that the world should be in flames and yet it remains resolutely unburning? The answer is, as Boudreaux points out, that wealth and income inequality are a lot less important than we're told they are:

One reason, I’m sure, is that rising inequality in monetary incomes or wealth is NOT the same thing as rising inequality in economic welfare (extra emphasis intentional). It’s not even close – although rare is the “Progressive” who acknowledges the reality that changes in income (or wealth) are not identical to changes in consumption-ability (that is, to changes in real economic well-being). Inequality of monetarily reckoned income or wealth can rise while inequality of consumption opportunities can fall.

We might want to worry about consumption inequality, if that does indeed become too extreme.But we've not particularly got very much of that in our current society. Sure, the plutocrats can have hot and cold running yachts and £10,000 bottles of champagne. But no one thinks that it's particularly important that they can and we don't. We've not particularly got a shortage of even a serious limitation on what we do care about the consumption of. A roof over our heads, decent food, nice clothes and so on and on. The rich may have nicer pants but they still put them on one leg at a time and they're still only wearing one pair at a time too.

The economically important form of inequality is that of consumption opportunities. And one good reason why we've not got those riots in the streets is simply that we've got a lot less of that than we do income or wealth inequality.

Are all macroeconomic models actually wrong?

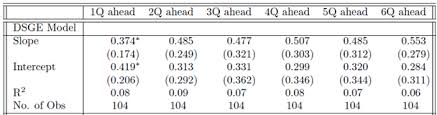

An excellent little spot by Noah Smith on who uses what sort of economic model to do their forecasting:

Suppose you’re a macro investor. If all you want to do is make unconditional forecasts -- say, GDP next quarter – then you can go ahead and use an old-style SEM model, because you only care about correlation, not causation. But suppose you want to make a forecast of the effect of a government policy change -- for example, suppose you want to know how the Fed’s taper will affect growth. In that case, you need to understand causation -- you need to know whether quantitative easing is actually changing people’s behavior in a predictable way, and how.

This is what DSGE models are supposed to do. This is why academic macroeconomists use these models. So why doesn’t anyone in the finance industry use them? Maybe industry is just slow to catch on. But with so many billions upon billions of dollars on the line, and so many DSGE models to choose from, you would think someone at some big bank or macro hedge fund somewhere would be running a DSGE model. And yet after asking around pretty extensively, I can’t find anybody who is.

One unsettling possibility is that the academic macroeconomists of the '70s and '80s simply bit off more than they could chew. Modeling a big thing (like the economy) as the outcome of a bunch of little things (like the decisions of consumers and companies) is a difficult task. Maybe no DSGE is going to do the job. And maybe finance industry people simply realize this.

And at this point we might be able to work out what's wrong with academic macroeconomics. It's not quite economics to simply shout "Follow the money!" but we can adapt that very useful idea of revealed preferences to tell us what's going on here. That useful idea being that we shouldn't look at what people say they'll do but rather at what they actually do. And we can argue that academic economists are trying to successfully predict what is going to happen as a result of changes in government policy if we should so wish to. But combine that with that follow the money idea and we'd expect the financial markets economists to have been subjecting their models to more rigorous testing. After all, real money is at stake, not just whether you manage to get published in one or another journal.

We should admit that this does rather play to our prejudices here. We're not great fans of macroeonomics at all, agreeing with Keynes that in the long run we're all dead but adapting that to insist that in the long run it's all microeconomics. Get incentives and the price system right and pretty much all other economic problems will either solve themselves or shrink to their not being problems that we want or need to worry about.

This of course enrages macroeconomists but as we don't get invited to their parties anyway we can shoulder this burden well enough.

Underneath that jollity though there is a much more serious point. Macroeconomics is really a very under developed approach of looking at the world. We rather take the Hayekian line that it always will be, given the dispersed nature of information and the impossibility of having enough of it in real time to be able to do anything useful with it. But that there's pretty much no one macro theory that you could get all macroeconomists to sign up to is another indication that it's really just not ready for prime time yet.

And if it's not ready for prime time then we really shouldn't be using it to try and guide our actions on the economy. We should, therefore, concentrate our efforts on those areas where we do know we've largely got the appropriate and necessary knowledge, about those incentives and that price structure.