Everything's coming up monetarist!

In "QE and the bank lending channel in the United Kingdom", BoE economists Nick Butt, Rohan Churm, Michael McMahon, Arpad Morotz and Jochen Schanz tackle the popular creditist view that movements in lending drive overall activity, and that quantitative easing works by stimulating lending, and find "no evidence to suggest that quantitative easing (QE) operated via a traditional bank lending channel". Instead, their evidence is consistent with the monetarist view, that "QE boosted aggregate demand and inflation via portfolio rebalancing channels." They find this result by looking at the difference between banks that dealt directly with the Bank of England when it was buying gilts (UK government bonds) with new money in its QE programme. If the creditist view held, these banks would be more able to expand their lending with the extra deposits created when the BoE hands over new money for gilts.

Our first approach exploits the fact that, for historical and infrastructural reasons, it is likely that not all banks are equally well placed to receive very large OFC (other financial corporation) deposits. We use historical data on the share of banks’ OFC funding (relative to their balance sheet) to identify a group of banks that are most likely to have received deposits created by QE, which we call ‘OFC funders’. We use this variable, along with variation in banks’ OFC deposit funding to test whether there was a bank lending channel by comparing the lending response of such OFC funders to that of other banks during the QE period.

They check their result by looking at gilt sales that commercial banks had no control over, since they were obliged to carry them out on the behalf of their clients. This makes them random with respect to those banks' separate funding and lending decisions, and isolates the effect of extra deposits created by QE on those banks' credit activity.

Our second approach makes use of the fact that while most gilt purchases were from OFCs, these had to be settled via banks who were market makers in gilts. As these gilt sales were likely to be unrelated to banks’ lending decisions, we can use data on gilt sales to remove the endogenous variation in banks’ OFC deposit holdings and so test for a bank lending channel using an instrumental variables approach that controls for the interrelatedness of the bank’s decision.

This paper only adds to a welter of recent studies supporting the monetarist perspective on the macroeconomy. "Institutional investor portfolio allocation, quantitative easing and the global financial crisis", another BoE paper released earlier this month found, like Butt et al., that pension funds and insurers rebalanced their portfolios in response to QE, moving away from gilts and into corporate bonds relative to what they would have done without the programme.

If firms rebalance their portfolios to reflect their preferences, then relative prices would not appear to be 'distorted' by the programme, and markets would still be performing their chief function—aggregating information so everyone can economise effectively and create wealth.

Another BoE paper, from April, "What are the macroeconomic effects of asset purchases?" found that:

Our results suggest that asset purchases have a statistically significant effect on real GDP with a purchase of 1% of GDP leading to a .36% (.18%) rise in real GDP and a .38% (.3%) rise in CPI for the United States (United Kingdom).

Finally, another new paper tells us that even the good old quantity theory of money is pretty good at forecasting post-war US inflation. Looks like everything's coming up monetarist!

£8 minimum wage hype: political trick, economic disaster, moral outrage

Britain’s Labour Party leader Ed Miliband says that a Labour government would boost the national minimum wage to £8 an hour, an increase of about £60 per week, by 2020. He says the UK economy is booming, and the low-paid should get a bigger share of it. Actually, at present rates of growth, the minimum wage will be close to £8 in 2020 anyway, so this is a one of those political sensations that doesn't amount to much. Even so, it is foolhardy now to commit UK businesses to pay any specific figure in 2020, since anything could happen in the meantime.

The minimum wage gets unthinking politicians (and not just Labour leaders) dewy-eyed. 'We can't have people being paid a wage that isn't enough to live on.' 'Businesses should pay their workers more, and take less profit.' 'The minimum wage hasn't killed jobs as the doomsayers say.' You know the story.

In fact, high minimum wages do destroy jobs. in particular, they destroy those starter jobs, the low-paid, temporary jobs that once gave young people their first step on the jobs ladder – pumping petrol (as I did), stacking bags in supermarkets, ushering people to their seats at the flicks. Now those jobs don't exist, because they are not worth the minimum wage (plus all the National Insurance and the burden of workplace regulation that goes with them – a particular burden on small firms). So we have a million young people out of work.

As for profit, try using that argument on anyone running a small business, already weighed down by taxes, rates, and regulation. Often they are getting less than their lowest-paid employees, and working longer hours for it Higher minimum wages mean they can afford to employ fewer people, or provide less generous perks and conditions.

I don't want to live in a country where people can't afford to live on what they take home either. That is why we have a welfare system, to top up the earnings of the lowest paid. We need a negative income tax – above the line, you pay tax, below the line, you get cash benefits – structured so that you are always better off in work than out of it. A paying job, even a low-paid job, is the best welfare system the human mind can devise.

And we must take low-paid people out of tax and national insurance entirely. Then more small firms could afford to take on more low-skilled workers and give them that first step on the jobs ladder.

If we could simply vote ourselves higher pay, why stop at £8? Why not fix the minimum wage at £800 an hour. The answer is obvious. The only people who would be worth that amount to anyone would be a few Premier League footballers, rock stars, investment bankers and high-class hookers. The rest of us would be out of a job.

The minimum wage does no harm to people who are already earning it, though it does them no good either. But it does positive harm to those earning less, or those who cannot get a job at all. The former will be let go, or will have to endure worse conditions; the latter will find it very much harder to get a job. And all that, of course, has already happened.

Central banks cause low interest rates, but not by lowering interest rates

The Bank of England slashed its discount rate ('Bank Rate') to 0.5% in its 5th March 2009 meeting in response to the growing recession, hoping to stimulate demand. Its discount rate is the rate it lends out to commercial banks—and a lower rate is believed to raise economic activity, whether through expectations, extra nominal income or increased lending. It has left it there ever since, and indeed, because of the 'Zero Lower Bound' on interest rates it has turned to other tools to try and bring about an economic recovery—a recovery which is only just setting in properly. When the Bank moves its key policy rate, commentators talk about it hiking or cutting interest rates; on top of this, we've seen extremely low effective interest rates in the marketplace; together this makes it reasonable to believe that the central bank is the cause of these low effective rates.

There are lots of reasons to doubt this claim. In a previous post I pointed out that the spreads between Bank Rate and market rates seem to be narrow and fairly consistent—until they're not. I made the case that markets set rates in an open economy. And I argued that lowering Bank Rate or buying up assets with quantitative easing (QE) may well boost market rates because they raise the expected path of demand, the expected amount of profit opportunities in the future, and thus investment.

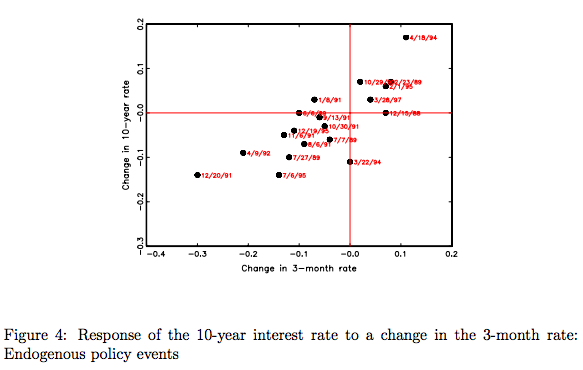

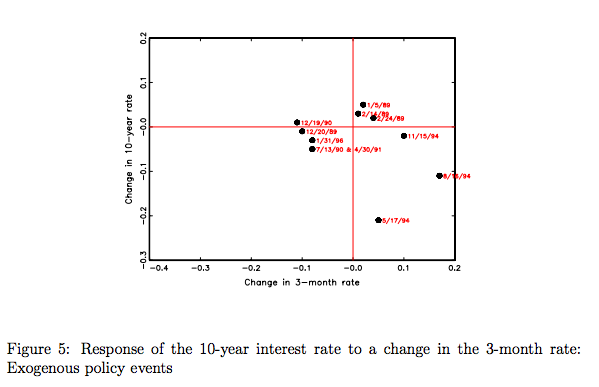

Since then I came across an elegant and compelling explanation of exactly why this is. In a 1998 paper, Tore Ellingsen and Ulf Söderström show that this is because some monetary policy changes are purely expected and 'endogenous' responses to economic events, whereas some monetary policy changes are unexpected 'exogenous' changes to the central bank's overall policy framework (like raising or lowering the inflation rate that markets believe they really want).

When changes are expected, market rates keep a tight spread around policy rates; when changes are a surprise, cutting Bank Rate actually results in higher interest rates in the marketplace.

To identify which changes were exogenous (surprises) and which changes were endogenous (expected) Ellingsen and Söderström looked at market commentaries in the Wall Street Journal the day after policy events—where the Fed decided whether to change or maintain its current policy rate. When traders they interviewed were surprised or disappointed by the move (or lack of move), they judged it exogenous—when traders explained the Fed's move in terms of changes in economic data they judged it endogenous.

This neatly explains why raising Bank Rate would not shut off bubbles (as an aside: a recently-published paper finds that tight, not easy money, is more closely associated with bubbles) and house price booms and so on. Cutting Bank Rate would raise market rates if it changed markets' perceptions of what target the Bank of England is working towards (i.e. made them think it wanted higher inflation). Conversely, if the Bank had decided not to look through high supply-driven inflation, and thus surprised markets by running tighter than expected policy, this would have been likely to push rates even lower.

The best way to get rates back to normal territory, thus incentivising firms to economise on investment projects and put cash into only the very best, is to make sure the economy doesn't suffer the effects of what Hayek called a 'secondary depression'. And the best way to ensure that is to implement something we might call a 'Hayek Rule' after the monetary policy he proposed—stabilising MV (the money supply x velocity, equal to aggregate nominal income). Recent work has shown that we get less creative destruction and capital reallocation in slumps as opposed to healthy growth periods.

Firm expectations now mean that setting this at zero, as he proposed, would have a very costly intermediate period while firms reset their plans—setting it at the rate consistent with 2% inflation (roughly 5%) would be more appropriate. Perhaps in the long run it could come down. But without a stable macroeconomic environment, capitalism cannot create the wealth that makes it so widely and dynamically successful.

The People's Republic of South Norwood

South Norwood, the unassuming splodge in the London Borough of Croydon is no more. Long live the People's Republic of South Norwood! You may not have noticed, thanks to a concerted media blackout by The UK Establishment (though the WSJ did get wind), but last Friday was the day of the Great South Norwood Referendum and the dawn of a new Republic. Inspired by the Scottish Independence movement and frustrated by the disdain with which local government treats the area, local heroes The South Norwood Tourist Board held a (definitely absolutely legitimate and totally binding) referendum for the community: Should South Norwood remain with Croydon Council, unite with an Independent Scotland, or declare their independence? The public spoke, and voted to boot out their uncaring and overbearing masters to go it alone with a whopping 53% of the vote.

It's hardly surprising that the downtrodden population of South Norwood had enough of Croydon Council, who have simultaneously ignored pleas to clean up and invigorate the area, whilst clamping down on displays of frivolity and fun. Notoriously, head of the Council's Health and Safety outlawed plans for the community-led 'Lake Naming Ceremony', inspiring a crowd of revellers (and a gang of Morris Dancers) to hold an illegal event in subversive defiance. It will be written in history that the naming of Lake Conan Doyle sewed the seeds of secession.

Now that South Norwood has established its independence it faces a number of tough questions. What does this mean for its governance and security, its relationship with the UK, and its currency? Addressing these will be challenging, but there's every indication that an independent South Norwood could thrive.

At first glance South Norwood is remarkably unremarkable. Long overlooked by pretty much everybody, it is yet to benefit from the gentrification of neighbouring Crystal Palace or the massive regeneration of Croydon town centre. Yet, with its blossoming community spirit (galvanized by the tireless tourist board), more lakes than the lake district, and a country park grown on top of an old sewer farm, its potential is undeniably huge.

Clearly, it is for the people of South Norwood to decide what shape their Republic takes. But as an ex-resident and dear friend of the area, I’ve outlined a few of the topics they need to address, and give a few suggestions on how to achieve a radical, yet roaringly successful Republic:

The first issue to tackle is that of governance. How shall people be ruled, and how shall laws be made? Should, for example, The Republic have a head of State? A symbolic one may suffice, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (who apparently lived there for a bit) or Pickles the dog (who discovered the stolen FIFA World Cup in a bush) are good contenders. There's also Ray Burns a.k.a Captain Sensible of The Damned, who already has a community garden installed in his honour.

Perhaps the people of South Norwood will opt for a proportional electoral system: with a population of about 14,000, the area's certainly small enough to adopt a straightforward proportional model, although PR creates the risk that Winston McKenzie, organizer of the infamous UKIP diversity carnival could hold some power. Going further, some form of direct democracy might even be possible. Regardless, electoral architects could do far worse than to read Douglas Carswell's iDemocracy for some inspiration.

However, we know that democracy can be troublesome, and that most voters are often (quite rationally!) spectacularly ignorant on basic political issues. What if democracy's not actually the 'least worst' system? One alternative, particularly for a Republic of such size, would be sortition- the selection of decision-makers by lottery. With its roots in Athenian democracy and still used in Jury service today, those selected could wise up on facts for the duration of their term and make decisions based on what's actually best for the Republic, instead of shoring up votes and a political career. There are other, more elaborate alternatives (such as Moldbug's suggestion that governments should be based on the profit motive, with bureaucrats seeking to increase their profits by boosting the value of the land, thus making it a lovely place to live) - but why not just abolish all government and embrace a form of market anarchism? It probably wouldn't be worse than the system the South Norwooders left.

Another pressing issue The Republic must address is that of their currency: what should an independent South Norwood use? Clearly, South Norwood could unilaterally adopt the pound without the permission of the UK, just as the ASI has argued for Scotland. Should PRSN wish to tie itself to the economic fate of the UK, it could -literally- just keep on using the pound. However, South Norwood could also protect its own economy and shore up against demand-side recessions by allowing private Norwood Banks to hold reserves of GBP and issue their own notes on a fractional reserve basis, adjusting the supply of money in response to demand. (Again, the detail's in the report!)

Admittedly, that does seem a bit excessive. Another option would be for South Norwood to issue their own currency (perhaps the Norwood Crown). Down the road the Brixton Pound is well-established and well-liked; those behind it could certainly lend a hand with an eye-catching design and the logistics of issuance. And with the news that Brixton is also scheduled to hold a referendum on its independence, perhaps a currency union is on the cards.

Yet the people of South Norwood have already shown themselves to be a tech-savvy, forward-thinking bunch, as evidenced by their use of a high-tech, online voting mechanism . So why not make Bitcoin SE25's new currency? If the Assistant Governor of Australia's Central Bank thinks its good enough for Scotland, it's probably good enough for South Norwood. In fact, they could go one further, and join Iceland, Cyprus, the Oglala Laktota Nation and others in creating their own national cryptocurrency. If they act quickly, they could beat Ecuador in creating the first government- ordained digital currency.

South Norwooders could adopt any of these options. But why not do away with legal tender completely and embrace free banking: the great people and businesses of the area accepting whichever competing currencies and payment methods (what about interpretative dance?) they so choose.

Clearly the most exciting part of forming an independent territory is deciding the guiding principles and policies to pursue. Again, such matters should be decided by the citizens, but here are a few pointers:

South Norwood should get in touch with the organziations who’s raison d’etre is to look at how to achieve growth and political and economic innovation within small, autonomous communities. Some groups such as Charter Cities and Startup Cities aim to create refuges of experimentation within amenable host nations. Others, such as the Seasteading Institute work within a paradigm of complete territorial autonomy and independence. Politically neutral, all of them value radical ideas, economic progress and the freedom for individuals to join such communities and innovate.

Tips on running a successful Republic can also be gleaned from examining things like Legatum's Prosperity Index, Heritage's Index of Economic Freedom, the Index of Freedom in the World and the Tax Competitiveness Index. Countries topping these rankings have probably got a few ideas worth borrowing.

The Republic could also look at which UK laws most need a radical overhaul, and lead by example. Planning laws are a key example. Far too many houses in the area are left vacant and boarded up, yet could be put to good use. Similarly, perfectly useable patches of land lie tangled up in legal battles and the quest for planning permission, sprouting brambles and dirty mattresses in the meantime. Liberalizing planning laws would allow creative uses of neglected spaces whilst providing the area with an economic boost.

The Republic should also embrace an open borders policy, as research repeatedly shows that reducing barriers to migration benefits both migrants and the culture and finances of the host country. An open Republic which builds on its cosmopolitan roots would be a successful one.

I encourage The Republic to experiment with radical new ideas. It could scrap alcohol duty, revitalizing some of the area's more shabby-looking pubs. Or it could legalise the consumption and production of Marijuana, using taxes levied on it to fund social expenditure. From there the UK's confusing, intrusive and expensive welfare system could be replaced with some form of Minimum Income or Negative Income Tax. Deer could be introduced to every park. Uber could run the public transport. The possibilities are endless.

It really is a brave new world for the people of South Norwood. The Scots may wonder if this is an omen for the success of their own referendum, but it's unlikely: even free-thinking South Norwooders eschewed the offer of being part of an independent Scotland. This is perhaps a shame, given the ASI's prior work on forging a union between Scotland and other countries seeking freedom from illiberal control.

Nevertheless, the prospect that Croydon Council refuses to accept the secession and continues to 'rule' its (ex)citizens with an iron fist is very real.

I wish all the best for The People's Republic of South Norwood. But whatever the outcome of their independence, it's good to note, on the eve of an even bigger, game-changing referendum, the diversity and breadth of untested policies and fresh ideas out there - and how many of these could make countries, communities and individuals happier, richer, more successful and freer.

It's the ineffable smugness that gets us

We're all aware of the manner in which the supermarkets have been one of the evil bugbears of our times. The manner in which the upper middle class commentariat has been outraged, outraged we tell you, at the manner in which anyone has the effrontery to offer the working classes cheap and convenient food. doesn't everyone realise that they should be buying at the butcher and greengrocer so as to subsidise the desires of the upper middle class commentariat? Which brings us to this lovely piece claiming that the age of the supermarket is now over and ain't that a good thing?

In my street, the light thunk of plastic boxes as they’re unloaded from the supermarket delivery vans is now as familiar, if not quite so uplifting, as the sound of my beloved’s key in the door. Those who use the internet for grocery shopping do it for reasons of convenience, certainly. But we also know we spend less online, buying only what we need, choosing necessities with a ruthlessness that often abandoned us in-store. What we used to spend on impulse buys – or some of it – then goes on a decent wedge of Lincolnshire Poacher, a couple of fillets of haddock or some good beef, sold to us by smiling, helpful, talkative people whose names we may know, and whose businesses matter both to them and us.

The people who run our supermarkets, obsessed as they are with “price matching” and “meal deals”, seem not to have noticed this. Or perhaps they have merely accepted there is no real way to respond to it. Small, local supermarkets are good and useful should you run out of stock cubes or Persil of a Tuesday evening. But even their expansion is finite. For the rest, there is no short-term solution. We have become suspicious: of their mawkish advertising, of their treatment of farmers, of their desperate bids to package up things that really don’t need packaging up at all (I mean this literally and metaphorically, versions of “restaurant-style” dishes being every bit as phoney and wasteful as apples wrapped in too much plastic). Modern life, we feel, is isolating enough without self-service check-outs. They want to own us, but we aren’t having it. Suddenly, the over-lit aisles of Tesco have never looked more bleak. Or more empty.

The problem with this is as follows. I've always said that supermarkets were horrible things and look, now people agree with me! That means I was right! But, no, sadly, it doesn't. It means that you might (assuming we accept the idea that the supermarkets are falling out of favour) be right now but it means that you were wrong before. Not in your personal taste of course: but in your projection of your personal taste to others.

And the point of emphasising this is that this is why we have markets. So that the consumer can decide for themselves how, in this instance, they wish to purchase their comestibles. If technology has changed so that internet delivery is now better all well and good. If it's simply consumer taste that has, equally well and good. The entire point of having competitors in a market is so that the consumer can, with each and every groat and pfennig they spend, intimate which of the possible offerings they prefer. On the grounds of price, taste, convenience, technology or any other differentiator.

If the supermarkets do go down (something we rather suspect won't actually happen) then it will not prove that those who campaigned against them in the past were right. It will prove that they were wrong: and further that their attempts to impose their views on others will always be wrong. For the very fact that supermarkets succeeded as a technology for however long it was or will be shows that they were wrong: and that they fail (as any and every technology eventually does) at some point will again show that that market process is the method of dealing with such matters. For, as is now being said, when the technology or consumer desires change then the market reacts and replaces the less favoured with the more. What else could you possibly want from a system of socio-economic organisation?

Strange fruit

Vishal was the 2014 winner of the Adam Smith Institute’s Young Writer on Liberty competition. The free trade of all goods and services seems likely to be optimal—however, given that there are countless lobbies and political pressures that make this situation currently infeasible, I will argue for the abolition of tariffs and restrictions on the trade of fruits and vegetables.

A global abolition of import tariffs and restrictions on fruits and vegetables would, on a static analysis, reduce tax revenue derived from them and increase demand for fruits and vegetables as their prices decreased. But dynamically, reducing the revenue derived from tariffs on fruits and vegetables may well be more than offset from the gains in labour productivity and the increase in national income (and tax revenues) that may result.

David Blanchflower, Andrew Oswald & Sarah Stewart-Brown (2012) found that, after controlling for various other factors, individuals who eat 7 fruits and vegetables a day are found to be significantly happier than those who do not. They further found that this improvement in psychological well-being is nearly as much as the increase in happiness from being employed versus being unemployed!

On top of psychological well-being, greater fruit and veg consumption may also improve general health—itself a benefit—and potentially freeing up healthcare funds. Furthermore, Andrew Oswald, Eugenio Proto and Daniel Sgroi (2009) found that there is evidence to suggest that happiness does raise productivity.

An increase in happiness would also be amplified by the dynamic, contagious effect of happiness: it would spread through the population, further amplifying the economic gains from the easing of import tariffs and restrictions. This phenomenon has been well documented, including in James Fowler & Nicholas A. Christakis (2008).

Some countries already have low import tariffs on fruits and vegetables (in the US tariffs on fruits and vegetables average less than 5% according to Renée Johnson (2014)). But there are several economies where the tariffs are substantially higher; more than three fifths of EU and Japanese tariffs on fruit and veg are between 5-25% and nearly a fifth exceed 25%. Other countries with relatively high import tariffs on fruits and vegetables include China, Egypt, India, South Korea and Thailand.

Perhaps most importantly, the abolition of tariffs and import restrictions on fruits and vegetables would be a big boost to society's least fortunate, a group particularly hard up during an economic crisis like that from which we are only just recovering.

The abolition of tariffs on fruits and vegetables would reduce their price and increase their consumption. The initial drop in tax revenue would be offset by both the direct improvement in psychological well-being and its contagion that would work to enhance labour productivity, national income, health and happiness. Let's pick the low-hanging fruit!

Explaining (part of) the UK labour productivity puzzle

Apologies, this is slightly wonkish....one of the puzzles of the current economic recovery is that labour productivity appears to be falling. This just isn't what we would expect to happen at this point in an economic cycle. Yes, we do expect it to fall substantially in an actual recession: employers lay off workers more slowly than output falls, meaning that each worker is producing less (the reason for the slowness of the layoffs being that firing someone now and rehiring in the good times costs money, there's stickiness in what happens here). And productivity we expect to grow strongly in the early stages of a recovery as people sweat that labour they've got as output increases rather than immediately going out to hire more people.

So we can happily explain much of what's happening in that chart using our standard assumptions. Then we get to 2011 and beyond and we're not sure what is happening there. We really don't expect to have falling labour productivity at that point. So what is happening?

We can't tell you exactly and precisely what is happening here: we can't even tell you how important this next point is to what is happening. But we can tell you that this is absolutely one of the things that is going on. Public sector wages are falling relative to private sector ones. That is part of the cause of that fall in labour productivity.

Here we enter a rather Alice in Wonderland area of economic statistics, the measurement of public sector labour productivity. In the private sector this isn't actually easy but it is at least logical. Stripped to its essence we add up the value of what is produced, look at the number of hours of labour required to produce that and divide one into the other. If there's more production from the same number of hours then labour productivity has risen. Obvious, really.

The important part here being that that "value" is "at market prices". But we cannot use this method for estimating public sector output. Because most of what the public sector does doesn't have market prices: how can we "value" the output of a diversity adviser?

Therefore we don't even attempt to do this. The output of government is defined as what we spend in order to gain this output. Thus public sector labour productivity is equal to, exactly the same as, the wages we spend on public sector labour.

This has, obviously, perverse effects. If we pay a nurse £25 an hour then we record her output as being £25 an hour. If we double her wages to £50 an hour then her output doubles: even as she ignores the same number of patients to do her paperwork. And note what happens to her productivity: it's just doubled just because we are paying her more.

There is no difference whatsoever in the output: but because of the odd way (through necessity) that we measure labour productivity in the public sector that productivity has just doubled.

This effect will also obviously operate in reverse as well. If we cut public sector wages then we will be cutting public sector productivity. It might be that we get the same actual output in terms of government from those newly more lowly paid civil servants. And that would normally be regarded as an increase in labour productivity: we're getting the same output for a smaller input. But this method we use to measure public sector labour productivity means that we actually record the opposite effect: lower public sector wages means we are spending less on government and thus we record that value gained from that labour as having fallen. We record labour productivity as falling when we cut public sector wages.

And what has been happening since 2011? Yes, that's right, there's been a deliberate attempt to reduce, relative to the private sector, public sector wages. As ONS tells us:

The average pay difference in favour of the public sector has narrowed since the year 2010, which in part reflects the restraints on public sector pay over this period

And we can look in more detail here (page 19 of the .pdf on that page). By the (controversial) way that ONS measures public sector pay (controversial because while it tries to measure qualifications, organisation size etc it's not adding in pensions accruals and job security etc.) this was lower than private sector in 2001 or so, grew higher than private through the years of the Brown Terror and now there's a deliberate attempt to manage it down again.

Whether you think those actions of the Brown Years, or the current ones, are justified or not is entirely up to you. But the implication of this for our recorded labour productivity figures is that some portion of that growth in labour productivity over the period 2001 to 2010, and some portion of the fall in it since, is simply the result of the boom and then restraint in public sector pay.

It is, in short, a measurement fault rather than an actual description of anything that is actually happening to labour productivity.

As at the top, we can't tell you how important this is: that would require a great deal more research. We can however tell you that this absolutely is at least a piece of the puzzle. Why is UK labour productivity falling? Simply because we measure public sector labour productivity by the amount we pay them in wages and we're deliberately squeezing those wages currently.

My thanks to the prolific commenter Luis Enriques for sparking this line of thought.

Apparently Owen Jones doesn't know what socialism is

This is a slightly strange error for Owen Jones to have to cop to. The One who would lead us all to the sunny uplands of a socialist economy doesn't seem to know what socialism is:

"The urge to punish all bankers has gone far enough," declared a piece in the Financial Times just six months after the crisis began. But if there was ever such an "urge" on the part of government, it was never acted on. In 2012, 2,714 British bankers were paid more than €1m – 12 times as many as any other EU country. When the EU unveiled proposals in 2012 to limit bonuses to either one or two years' salary with the say-so of shareholders, there was fury in the City. Luckily, their friends in high office were there to rescue their bonuses: at the British taxpayers' expense, the Treasury took to the European Court to challenge the proposals. The entire British government demonstrated, not for the first time, that it was one giant lobbying operation for the City of London.

Bankers are employees of banks. The employees of an organisation having an ownership right in the profits of that organisation is a form of socialism. In a capitalist organisation the profits would flow, uninterrupted, to the shareholders, not the employees.

The current structure of banking pay in London, with those bonuses, is more like the profit share at John Lewis, of the divvie to the customers at the Co Op, than it is to anything reminiscent of hard line capitalism.

Socialism, despite what Jones may think, is not just whatever he approves of just as the definition of capitalism or free markets is not the same as whatever we approve of here.

By the way, shouting about how 12 times more bankers got big paychecks in the UK than the rest of the EU is simply evidence of the fact that the European finance (indeed, the largest portion of the international, global) industry is largely based in London and The City. It's no more surprising than finding out that the majority of people paid to make Parma ham are in Northern Italy, the majority of those making Stilton are somewhere north of Watford Gap or that there's a definite shortage of those paid to herd reindeer in lands where olive trees thrive.

Good grief, even Karl Marx managed to get to grips with the implications of Ricardo and comparative advantage. Might be worth Jones giving that a crack.

So, just what is this economics stuff good for?

Mark Wadsworth asks us an interesting question:

Reading this and this got me thinking.If we think that we know all this stuff, the temptation - on the part of prodnoses - is to use it to interfere.

Alternatively we could think of economics as a discipline that tells us why we need to tell those prodnoses to bugger off.? That is its best purpose. Telling people why they should NOT do stuff.

Is economics best use as a negative or positive thing?

Discuss and inform me.

The answer comes from Ben Bernanke:

Economics is a highly sophisticated field of thought that is superb at explaining to policymakers precisely why the choices they made in the past were wrong. About the future, not so much. However, careful economic analysis does have one important benefit, which is that it can help kill ideas that are completely logically inconsistent or wildly at variance with the data. This insight covers at least 90 percent of proposed economic policies.

Yes, sometimes we can propose sensible things as a result of having consulted the economic runes. But the real value is that 90% of the time we can tell damn fools that their damn fool plans are damned foolish.

Nationalisation, rent controls, price controls of all kinds, trade barriers, infant industry protection....there's a long list of things that people propose again and again, even if vanquished they'll pop up a generation later. The value of economics is that not only can we point out that they're damned foolish but even why they're damned foolish.

Economists are morally superior beings, scientifically proven that is

A lovely paper discovered by Paul Walker over in the land where Kiwis live standing on their heads:

Does an economics education affect an individual's behavior? It is unclear whether differences in behavior are due to the education or whether those who choose to study economics are different. This issue is addressed using experimental evidence from the Trust Game where trusting and reciprocating behaviors can be measured. First, it is shown that economics students provide greater trusting investments and reciprocate more. Accounting for the selection effect, these effects are explained by those who choose to study economics and not directly from the education being provided. Thus, economists play well with others and these social preferences are not taught in the classroom.

We who have studied economics are thus morally superior because we do play nicely with others: the reasons being that playing nicely with others is the reason we went to study economics.

Well, Hurrah! for that.

However, this does pose a problem for us as we try to explain it to others. For we're, in some manner, captivated by those very examples of playing nicely together than the market offers us. We can see how competition is the method by which we decide who to cooperate with and that the vast majority of economic activity isn't in fact competition at all, it's cooperation. The seemingly vast and impersonal market itself is simply a description of how we all, the many billions of us, choose to cooperate to our mutual advantage.

Great, excellent and it's all true. But note what the paper is telling us. We're, because we chose to study economics, inclined to believe all of that anyway as that's the way our own personalities work. But our task is to get across the points about such cooperation to those who simply do not have those same basic beliefs about human behaviour that we do. No wonder it sometimes comes out as a dialogue of the deaf: we don't get what they don't believe at root, that humans are naturally cooperative beings and markets are the way that we do this.

Thus, we might posit, the existence of this idea that trade, the economy itself, is a zero sum game. We have one view of human nature, they another and the fact that ours is correct doesn't matter so much as the fact that they don't believe us or the main point itself.