Why do people oppose immigration?

My Buzzfeed post on immigration generated a bit of traffic yesterday and a bit of disagreement, too. The most common objection to our approach to immigration is that it's one-dimensional—OK, we might be right about the economics, but c'mon, who really cares? It's culture that matters. This point was made to me a few times yesterday and there's definitely something to it. My first response is that I think people underestimate the public's ignorance of the economics, and hence the public's fears about immigration. This poll by Ipsos MORI (I love those guys) asked opponents of immigration what they were worried about—as you can see, their concerns are overwhelmingly about job losses and the like:

The top five concerns are all basically to do with economics, with the highest-ranking cultural/social concern getting a measly 4%.

Obviously this isn't the whole story. People might be lying to avoid seeming "racist", for example. But in other polls people seem less reserved—last year 27% of young people surveyed said that they don't trust Muslims. Less than 73% of the population say they'd be quite or totally comfortable with someone of another race becoming Prime Minister, and less than 71% say they'd be quite or totally comfortable with their child marrying someone of a different race. So the 'embarrassment effect' of seeming a bit racist can't be that strong, and clearly the ceiling is higher than 4%.

I reckon it's more likely that people have a bunch of concerns, of which the economic ones seem more salient. Once they've mentioned them, they don't need to add the cultural concerns to the pile. Either that, or we just believe people in the absence of evidence to the contrary.

That's why I think it's legitimate to focus on the economics of immigration, even if we concede that the cultural questions are important (and tougher for open borders advocates to answer). Persuading some people that their economic fears are misguided should move the average opinion in the direction of looser controls on the borders.

If we could put the economic arguments to bed we might be able to have a more productive discussion about immigration. If culture's your problem, then let's talk about that, but remember that the controls we put on immigrants to protect British culture come with a price tag. Maybe we'd decide that more immigration was culturally manageable if we ditched ideas like multiculturalism and fostered stronger social norms that pressurised immigrants into assimilating into their new country's culture. I don't know. (Let's leave aside my libertarian dislike of using the state to try to shape national culture.)

The point, for me, is this: the economics of immigration does matter a lot to people. Immigration is not either/or—we can take steps towards more open borders without having totally open borders. At the margin, then, persuading people about the economics of immigration should move us in the direction of more open borders. And that, in my view, makes the world a better place.

Longevity and the rise of the West

Did the Industrial Revolution happen because of improvements in institutions or because of improvements in human capital? A duo of new papers attack the question from an interesting new angle, looking at longevity, and finding that its rise precedes (by a good 150 years) the onset of the Industrial Revolution. The first, a 2013 study from David de la Croix and Omar Licandro, builds a new 300,000 strong database of famous people born from 2400BC to 1879AD (the year Einsten was born) and has four key findings (pdf) (slides):

- On average, before the cohort born in the 1640s, there is no trend in lifespans; they stay at an average of 59.7 years for 4,000 years

- Between the cohort born in the 1640s and Einstein's cohort, longevity increases by 8 years—this trend pre-dates the industrial revolution by generations

- This increase occurred across Europe, not just in the leading advanced countries

- This came from a broad shift, rather than a few especially long-lived individuals

The second, published less than a month ago by LSE economic history professor Neil Cummins, makes use of an even more innovative source of data—a collaborative project between the Mormon Church of Latter Day Saints and individual genealogical experts. Apparently the LDS is a major collector of genealogical information:

‘Baptism for the dead’ is a doctrine of the church of Jesus Christ of the Latter Day Saints(LDS). The practice is mentioned in the Bible (Corinthians chapter 15, verse 29, TheHoly Bible King James Version (2014)). The founder of the LDS church, Joseph Smith,revived the practice in 1840 and ever since, church members have been collecting historical genealogical data and baptizing the dead by proxy. The church has been at the frontier of the application of information technology to genealogy and has digitized a multitude of historical records. Today they make the fruits of their research available online at familysearch.org. The records number in the billions.

The paper draws longevity statistics on 121,524 European nobles who lived between 800AD and 1800AD to establish that the West was rising even before the marked gains seen from the 1640s, and suggesting that the roots of economic development go very deep (much deeper than institutions).

The fascinating paper is saturated with insight-nuggets. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the top ten exact death dates in the periods are all battles:

There's also extra support for Stephen Pinker's thesis of massively declining violence in society:

And here's the overall result:

Taken together, the papers seem to provide strong support for the human capital thesis, as against the idea that changes in institutions were key in allowing humans to escape from the Malthusian trap and see general rises in the living standards, for the first time ever.

So where has all of Keynes' leisure gone?

In Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren Keynes famously proposed that by about now we'd all be working 15 hours a week. As a result we've had endless little reports from the likes of the not economics frankly people suggesting that we should all indeed work only 15 hours a week and spend the rest of our time being poor. But there is another answer, the correct answer, to where all of Keynes' predicted leisure time has gone:

Women devote well over the equivalent of a working day each week to household chores – double the amount undertaken by men.They spend an average of 11-and-a-half hours doing housework, while men complete just six.

A survey, commissioned by BBC Radio 4's Woman's Hour, found cooking was the most popular job.

Women said their chief responsibilities included changing sheets (86 per cent) and cleaning the toilet (83 per cent).

Whereas men were in charge of bins (80 per cent) and DIY (78 per cent).

The least popular tasks for both sexes were loo cleaning and ironing.

Keynes was proposing that as we got richer then we'd take more of our increased wealth as leisure. Which we have, in terms of our market working hours, to some extent at least. In the 1930s Saturday was still, for many, at least a half-working day. The standard 37.5 hour week of today would have been regarded as being near a part-time rather than full-time work load. But the real reduction in working hours has come as a result of the mechanisation of household production. Those microwaves, vacuum cleaners, gas ovens, central heating and so on, what Ha Joon Chang and Hans Rosling refer to collectively as the "washing machine", have led to a massive drop in the hours spent on running a home.

It would be stretching it a bit to say that a housewife in 1930 was working 11.5 hours a day on housework but not much: it was certainly 8-10 hours a day, very much a full time job. And it's that labour that just isn't being done any more: leading to the explosion of leisure time that we all currently enjoy. Keynes was right in that we've taken more of our increased wealth in the form of leisure. It's just that we've taken it from the non-market, household, part of our labours rather than the market and paid side.

Where does Will Hutton get these ideas from?

This is just fascinating from Will Hutton:

The fall in real wages is blamed on EU immigrants, when the real culprit is more old-fashioned: workers in general, and young workers in particular, have not been organised enough to offer countervailing labour market power. It is not technology, globalisation or immigration that have triggered such a generalised collapse in real wages – it is the weakness of trade unions.

Where does this confident assertion come from? He provides us with no actual evidence to support it. Just the flat statement that it is so because Will Hutton has declared it to be so.

This is a statement that rather needs to be tested, don't you think? For example, unions are rather stronger in Germany than they are in the UK. Real wages have been declining in Germany:

After a decade of falling real wages, Germans’ purchasing power has started to increase over the past few years. In 2013, wage hikes are clearly outpacing inflation on the back of rising employment and a robust economy.

Unions are rather weaker in the US private sector than they are in the UK. And we all know the complaints about the stagnation and possibly fall in real wages over there.

We even have a report about this. The effects of globalisation upon incomes around the world. By a real economist using actual real data. The finding of which is that the people who haven't seen much gain from globalisation, the people who have had those stagnant real incomes as a result of it, are largely those below median incomes in the already rich countries. We can argue about whether that makes it all worth it or not (the 80% rises in income for almost all of the poor of the world make it so for us) but it's very definitely evidence that it's not the absence of unions that has led to the current situation: it's globalisation.

So where does Willy get his confident assertion from?

Beware the people promoting infrastructure spending

The IMF has told us that building infrastructure can pay for itself. This is, of course, true. However, we do need to be rather careful about the implications of that fact. for while it's entirely possible for something to pay for itself that doesn't mean that everything will do so:

The study finds that increased public infrastructure investment raises output in the short term by boosting demand and in the long term by raising the economy’s productive capacity. In a sample of advanced economies, an increase of 1 percentage point of GDP in investment spending raises the level of output by about 0.4 percent in the same year and by 1.5 percent four years after the increase (see chart, upper panel). In addition, the boost to GDP a country gets from increasing public infrastructure investment offsets the rise in debt, so that the public debt-to-GDP ratio does not rise (see chart, lower panel). In other words, public infrastructure investment could pay for itself if done correctly.

The words to concentrate upon are those last three "if done correctly". For no, this does not mean that bunging £40 billion at a train set will pay for itself. Nor that damming the Severn Estuary will nor any other of the various plans people are floating. As Greg Mankiw says:

Certainly this outcome is theoretically possible (just like self-financing tax cuts), but you can count me as skeptical about how often it will occur in practice (just like self-financing tax cuts). The human tendency for wishful thinking and the desire to avoid hard tradeoffs are so common that it is dangerous for a prominent institution like the IMF to encourage free-lunch thinking.

It still depends upon what you're building and where you're building it and how you're building it.

Markets don't like racism

It is a commonplace to the point of boringness among advocates of free markets that they make people pay to discriminate based on their tastes. A factory owner who restricts employment to whites only will face a narrower talent pool—likely paying higher wages for lower skills in total or on average. Southern US states had to pass laws to try and stop employers competing with each other over black labour and bidding up their wages.

Even owners of basketball clubs believed to be personally racist have disproportionately black teams, paying them huge sports star wages. However, not all ethnic groups have similarly prestigious or high-flying careers, and they do not all take home equal market incomes. It would be easy to jump to the conclusion that taste-based discrimination is driving this and the market isn't doing its job fully. But there is an alternative.

Employers cannot observe an employee's productivity directly, at least before they employ them. But they can observe some things about them that signal productivity—using statistics. For example, if on average south Asians or Polish migrants tend to work harder than white Brits, they can use this fact about them to help make their employment decision. This isn't racist—they don't prefer employing south Asians, and they would be equally happy to pay a white Brit £6.50 an hour to produce £7 of stuff—it's just that on average south Asians produce £7 of stuff an hour (say), whereas white Brits produce £6.40.

Which one is actually in place? We can test this. The answer is a resounding 'statistical discrimination'. For example, minorities in France did worse when a large randomised study made them anonymous in job applications—so firms couldn't see their names and thus ethnicities—implying that the reason they were called back and employed less was because their resumes/CVs were less attractive.

In Germany, job applicants with Turkish-sounding names got less callbacks than those with German-sounding names—unless both applicants had a favourable employment history reference. Then, for a given quality of reference, employers didn't care whether they were Turkish or German. On eBay, white sellers receive lower prices selling stereotypically black products and black sellers receive lower prices selling stereotypically white products, but these differences go away when sellers build up credible reputations.

US "landlord response rates across neighborhood racial compositions conform to the statistical discrimination model where agents use past experience to predict applicant quality by race." In the Israeli used car market there is "robust evidence of discrimination against Arab buyers and sellers which, the analysis suggests, is motivated by ‘statistical’ rather than ‘taste’ considerations." In an experiment selling iPod Nanos online, its being held by a black hand made buyers warier, to a similar degree as its being held by a tattooed white hand.

People do no racial discrimination whatsoever, and choose entirely based on expected points return, when picking their fantasy football team. Finally, even most of shared renting decisions in London are based on statistical concerns (some ethnic groups commit more crimes per capita), rather than personal preferences over races and ethnicities.

It is perfectly well and good to lament the fact that for whatever reason, some ethnic groups are less qualified, systematically less hard-working, achieve worse educational results, commit more crimes or whatever. This might be the result of discrimination on some other margin. But we can be pretty sure that markets are picking only on the criteria we want them to use.

Are the markets wrong about CEO pay and the recovery?

CEO pay has risen by 937% since 1978 in the US, compared to a rise of just 10.2% for the average American worker, according to a centre-left American think tank. That feels like markets must be wrong, but as Scott Sumner points out, when market decisions and our intuitions clash, we're often the ones at fault:

CEO pay has been controversial for two reasons. It has risen very rapidly in recent years, and it often seems unlinked to performance. But pay is very closely linked to expected performance, which matters when contracts are signed. A few months ago Steve Ballmer resigned as CEO of Microsoft and the stock rose by billions of dollars. More recently, Larry Ellison (sort of) stepped aside from Oracle, and the stock plunged by billions of dollars. This shows that CEOs have a huge impact of stock valuations. Whether the market is rational in believing that is a trickier question, but it's the job of corporate boards to put people in place that will maximize shareholder value. That means they need to at least try to get the very best, even if it costs a lot of money in terms of higher salary. If they aren't paying obscene salaries then the board of directors isn't doing its job.Back in the 1960s, corporate decisions were much easier. You allocated capital to new auto factories, steel mills, appliance makers, and churned out product for which you knew consumers were waiting. Even IBM was fairly predictable for a time. In contrast, a modern CEO at a high tech firm might find the company quickly destroyed by new technology if he doesn't keep on his or her toes. Think how much Sony would have benefited in the past 10 years if it had had the Samsung management team. Perhaps an extra $100 billion in shareholder wealth? And that's also why the finance sector is so much more important today, decisions over where to allocate capital are both more difficult and much more important.

In other words, CEO pay may have risen a lot because CEOs matter a lot more, relative to the average worker, than they did in 1978. You could just deny this, because nobody is 'worth more' than others, and so on, but that's an emotionally biased response. In terms of cold, hard cash, people are worth different amounts.

The market's valuation of CEOs might turn out to be wrong, of course – markets misjudged the future returns of a lot of assets in the run-up to 2008, but then, so did virtually everyone else. The question is what, in a world where anyone can be wrong, we can look to as the least-bad way of collecting and judging existent information.

Pundits on Twitter and in the media can make a living by being wrong. Look at, say, the Guardian's editorial writers or, if you tend to agree with them, the Telegraph's. Or look at any think tank – except us, of course. Or financial advisors. Pundits don't really suffer if they add 'noise' (a nice word for bullshit) to the sum of information that's out there, so it's hard to know if the pundit you're listening to is telling you what you want to hear, or what's actually true.

Markets – the people who make financial decisions that are aggregated in stock exchanges and the like – do. If you have a 'false belief' as a trader or business owner, you'll lose money; if you have enough false beliefs, you'll go bankrupt. And markets are utterly brutal in bankrupting people with false beliefs. We might have a good reason to ignore markets if we know something that they don't, but if that's the case, we should be making money from that private knowledge. Doing so will add that knowledge to the sum total of the market's knowledge.

This is why I'm an optimist. Lots of my friends and people I agree with on nine out of ten issues think that the markets are wrong and that some economic catastrophe is coming. If they're right, markets are wrong and they should be in line to make a lot of money (he said sarcastically).

So how can I judge? I look at who has more to lose, and who has a better track record. Through that lens, markets come out top – and my doomsaying friends sound just as biased as their opponents who just can't imagine why a CEO would be worth paying a lot.

An interesting little story about path dependence

There's no particular theoretical reason why the Burnley Miner's Social Club should be the world's largest consumer of the Benedictine liquer. There's also no theoretical reason why it shouldn't be: which is good for the fact is that it is. It's a useful reminder of two things, the first being path dependence:

A working men's club in the north of England is the world's biggest consumer of French Benedictine liqueur, downing 1,000 bottles a year of the alcoholic beverage.

The golden tipple has been a favourite at the Burnley miners' working men's social club for more than a century after being popular among soldiers who developed a taste for it during the First World War and drank it to keep warm.

Since then the drink has become a best seller at the 600-member club – which has even introduced a 'Bene Bomb' in a bid to keep it popular among the younger members.

There really isn't going to be any other 600 member club that gets through a 1,000 bottles a year of the stuff. The fist of our wider points being to point once again to the idea of path dependence. Things that happen today are often as they are because of some other thing that happened in the past. Perhaps the Dvorjak keyboard is better than he qwerty, perhaps it isn't, but the reason we don't use it today is because it definitely wasn't better with mechanical typewriters. Qwerty was deliberately designed, for purely mechanical reasons, to stop people typing too quickly. How we do things today is dependent upon things long irrelevant but important at the time we started the activity.

The second of course being that sometimes things just happen. You can see how the Benedictine story started: someone in one of those regiments got ahold of a bottle and told his mates how good it was. A century later it's still going on. The habit survives just because of that original happenstance and the social reinforcement of it over time. As with driving on the left or the right. Unlike Dvorjak there's no particular merit to either system, no basic reason to choose one or the other: and different places have chosen differently over the years (Sweden changed over from one to the other in, umm, the 1950s. Sadly, the story about the buses changing sides a week before the cars isn't true).

The world can make a lot more sense if we keep in mind that stuff really does just happen sometimes and the effects can be with us centuries later.

Getting it entirely wrong on fatcat CEO pay

An interesting little piece of research over at the Harvard Business Review. What do people think the difference between worker and CEO pay is and what do they think it should be? The research is interesting it's just that the conclusions people are likely to draw from it are entirely mistaken. The result won't surprise many:

We’re currently far past the late Peter Drucker’s warning that any CEO-to-worker ratio larger than 20:1 would “increase employee resentment and decrease morale.” Twenty years ago it had already hit 40 to 1, and it was around 400 to 1 at the time of his death in 2005. But this new research makes clear that, one, it’s mindbogglingly difficult for ordinary people to even guess at the actual differences between the top and the bottom; and, two, most are in agreement on what that difference should be.

“The lack of awareness of the gap in CEO to unskilled worker pay — which in the U.S. people estimate to be 30 to 1 but is in fact 350 to 1 — likely reduces citizens’ desire to take action to decrease that gap,” says Norton.

It really shouldn't surprise that an awful lot of people are remarkably ignorant about the world that they inhabit.

The error though is in what is then assumed should be done about it. For of course you can already hear the screams (from people like the High Pay Commission) insisting that as the average voter doesn't want there to be this income disparity therefore there should not be this income disparity. The error being that what the CEO of a large company gets paid is none of the damn business of the average voter.

It's the business of those doing the paying: and if the shareholders in a company wish to pay the person managing their business handsomely then that's entirely up to them. Nothing to do with the jealousy of the mob at all.

There is a small coda: some argue that it's the same old interlocking boards that keep raising the CEO's pay, knowing that their own will get raised in turn. The theory that the managerial class is ripping off the owners, the shareholders. It's true that this could happen, principal/agent theory is true. However, if this were true then private equity would be paying their managers considerably less than public companies do as they would not be subject to this rip off. Given that in reality, out here in the world, private equity pays very much better than public companies do then this isn't true either.

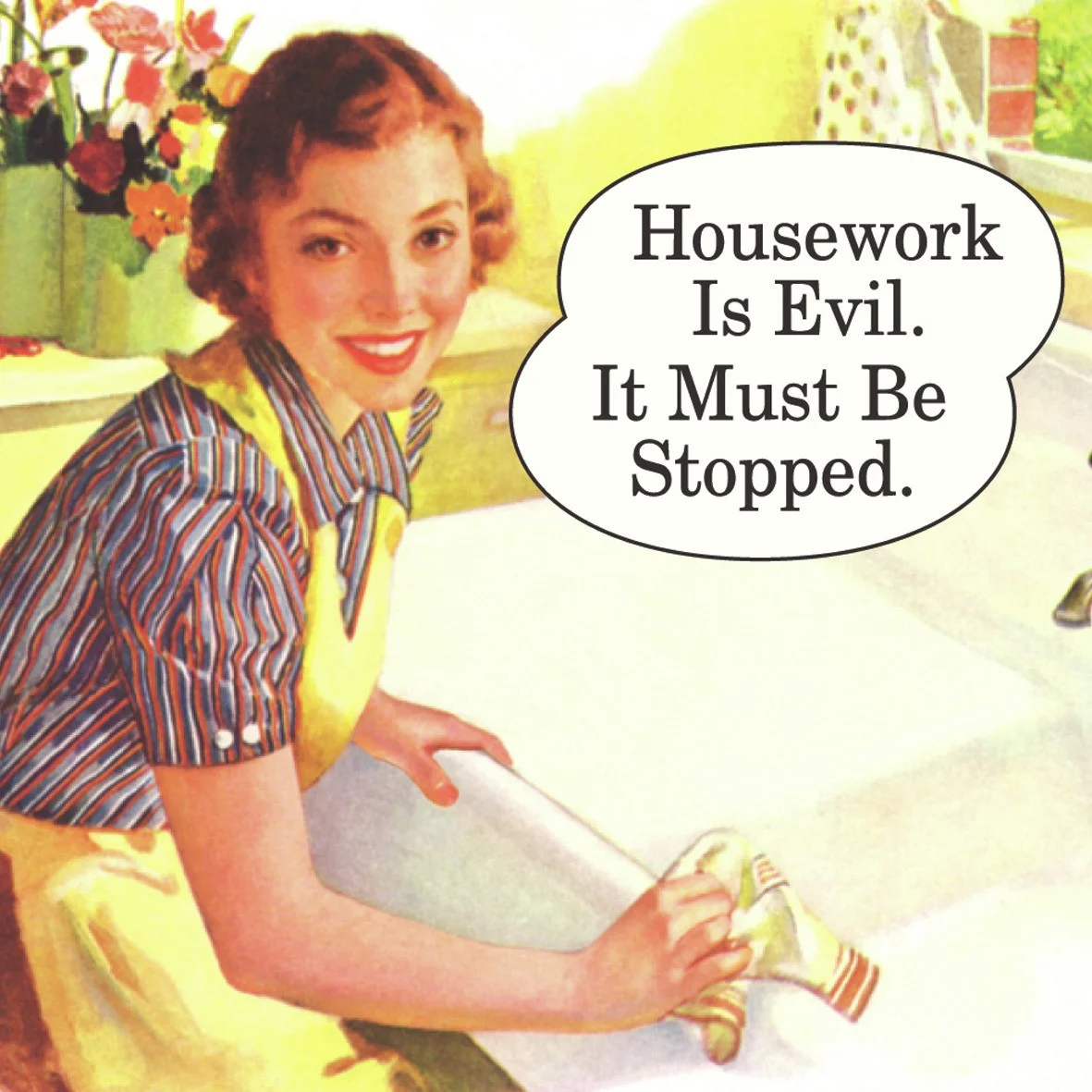

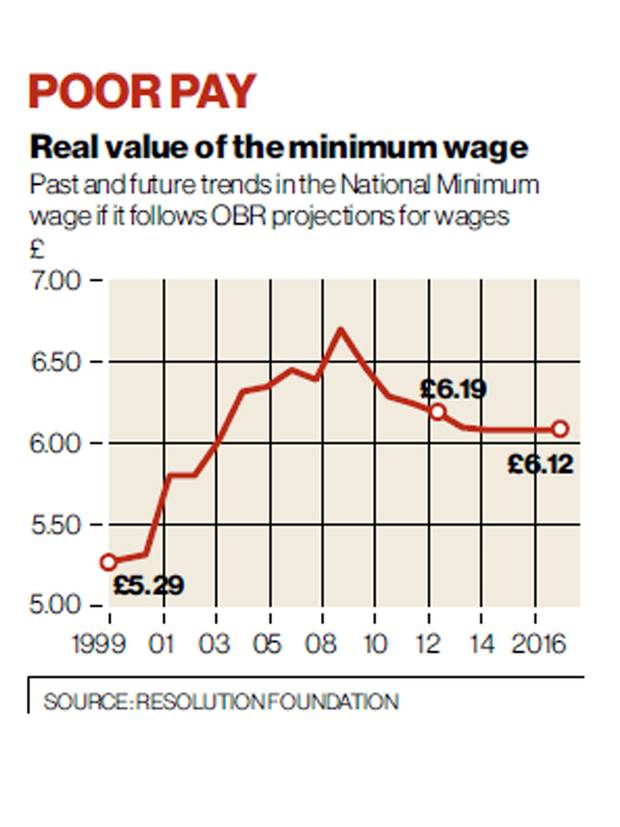

On Unite's demand for a £1.50 rise in the minimum wage

Howard Reed has done this particular piece of pencil sucking research for Unite to back up their demand for a rise in the minimum wage of £1.50 an hour. They're very proud of the fact that this would increase the amount of tax paid. Which doesn't really strike us as being all that good an idea really. Hoovering more money out of the wallets of the lowly paid never does sound like a good idea to us but we assume that things are seen differently over in unionland. But in the report they also say this about the macroeconomic effects:

A £1.50 per hour increase in the National Minimum Wage has three potential multiplier impacts on UK GDP: • The wages impact: the increase in net incomes arising from the increase in gross wages should lead to increased consumer demand which has a positive multiplier impact on GDP. • The profits impact: the reduction in net incomes arising from a decrease in profits may lead to reduced consumer demand which would have a negative multiplier impact on GDP. • The public finances impact: the increase in income tax, expenditure tax and NICs receipts and the reduction in benefit and tax credit spending leads to an improvement in the public finances even after taking into account increases in the public sector wage bill and reductions in corporation tax revenue. This means that government spending does not need to be cut as badly as current plans suggest. If the improvement in the public finances is matched by an increase in government departmental and investment spending – so that the overall government fiscal position is unchanged – then there should be a positive multiplier impact on GDP.

Reed also looks at the number of jobs that will be lost from that rise in the minimum wage and, hey presto, finds that more will be created than lost. He manages this by taking the lowest estimate of unemployment to be created he can find and the highest one for the number of jobs to be created available.

Hmm. Think we'll file this report in the policy based evidence making file, that round one under the desk, shall we?