Equal pay for equal work

A recent speech by Andy Haldane, the Bank of England's chief economist, sheds a good deal of light on the cost of living crisis and the union-led "Britain Needs a Payrise" campaign. Haldane points out how grim the recent situation has been for real wages in the UK economy:

Growth in real wages has been negative for all bar three of the past 74 months. The cumulative fall in real wages since their pre-recession peak is around 10%. As best we can tell, the length and depth of this fall is unprecedented since at least the mid-1800s.

But is this because employers have suddenly become selfish capitalists, whereas before they were paying workers out of the good of their heart? Or is something else at play?

Productivity – GDP per hour worked – was broadly unchanged in the year to 2014 Q2, leaving it around 15% below its pre-crisis trend level. The level of productivity is no higher than it was six years ago. This is the so-called “productivity puzzle”. Productivity has not flat-lined for that long in any period since the 1880s, other than following demobilisation after the World Wars.

We usually think that wages and productivity will be pretty closely related. Employers are unlikely to consistently pay above productivity, because they'd lose money. But equally, they'll be unable to consistently pay far below productivity (less the share needed to rent the capital involved) because in a reasonably competitive market firms will compete their workers away with more attractive job offers.

We might think this is particularly true at the low wage end of the market, because much less of low-skilled workers productivity is job specific. An accountant makes a very poor lawyer, and a civil engineer is not qualified to write code, but a worker in McDonalds will be similarly good at Burger King, or for that matter Waterstones, JR Wetherspoon, Lidl or most other relatively low-skilled areas.

So basic economic models suggest pay will track productivity. And what do we see on the macro level?

The deficit in pay tracks the deficit in productivity. Of course, the situation for public sector workers is a bit different—we actually measure their productivity mainly by inputs. If their pay goes up, their measured productivity goes up. It's hard to see how else we would do it. But the overall picture suggests that the real pay decline is down to a real productivity decline. We haven't moved away from equal pay for equal work—we've just had a big horrible recession and a sluggish recovery!

Unsurprising: Migrants give back to new communities (often more so than natives)

Migrants in high-income economies are more inclined to give to charity than native-born citizens, this Gallup poll finds.

[High-income economies are referred to as "the North"/ middle- to low-income economies are referred to as "the South".]

From 2009-2011, 51% of migrants who moved to developed countries from other developed countries said they donated money to charity, whereas only 44% of native-born citizens claimed to donate. Even long-term immigrants (who had been in their country of residence for over five years) gave more money to charity than natives–an estimated 49%.

Even 34% of migrants moving from low-income countries to high-income countries said they gave money to charity in their new community – a lower percentage than long-term migrants and native-born citizens, but still a significant turn-out, given that most of these migrants will not have an immediate opportunity to earn large, disposable incomes. The poll also found that once migrants get settled, their giving only goes up.

Migrants seem to donate their time and money less when moving from one low-income country to another; though as Gallup points out, the traditional definitions of ‘charity’ cannot always be applied to developing countries, where aid and volunteerism often take place outside formal structures and appear as informal arrangements within communities instead.

It’s no surprise either that the Gallup concludes this:

Migrants' proclivity toward giving back to their communities can benefit their adopted communities. Policymakers would be wise to find out ways to maintain this inclination to give as long as migrants remain in the country.

This is yet another piece of evidence that illustrates the benefits of immigration for society as a whole. (It also highlights the insanity of Cameron's recent proposal to curb the number of Eurozone migrants coming to the UK). Not only does the UK need more immigrants “to avoid a massive debt crisis by 2050,” but apparently it needs them for a community morale boost as well.

How to fix the Eurozone

It's rare that an economic question is clear cut. Nearly all issues are two sided, with substantial costs and benefits to all approaches. But the reason the Eurozone crisis has resumed is pretty obvious—'bad' disinflation and deflation almost universally across the bloc, and a failure of the European Central Bank to provide even the most basic monetary stability. The solution is equally obvious: meet the inflation target and commit to a level target to prevent future cock-ups. Household, firms and sovereigns take out (nearly all of) their debts in nominal terms, i.e. not adjusted for inflation. They are likely to build in expected inflation. However, if inflation is higher than expected, debtors incomes should rise faster than they expected, while their debt is still fixed, making the burden lighter. Of course, this means creditors receive less than they expected. It's the same on the other side.

If the central bank promises 2% inflation per year over the next ten years, and the markets believe it, then the yield of a gilt that matures in 10 years will take this into account. This goes (approximately) for all other assets in the economy, like mortgages, consumer credit, business loans and so on. If inflation departs from target it enriches one side at the expense of the other, contrary to what they all could have reasonably expected when they signed these contracts.

There is a complication: there is a difference between the inflation and deflation caused by supply shocks and that caused by demand shocks. When prices rise because everything really has become more costly to produce (a supply shock like an OPEC oil price hike) then this makes debts harder to pay, but worth no more. When prices fall because everything has become cheaper to produce (a supply shock like Chinese labour coming onto the world market) this makes debts easier to pay, but worth no less. But central bank expansions and contractions are demand shocks, not supply shocks.

This means that the national debt will be harder to pay if inflation comes in lower than target for monetary reasons. Inflation has been below the European Central Bank's target for nearly two years, and is falling further below it. Twelve countries have either zero inflation or deflation. Unless there were massive supply-side improvements across the Eurozone—which we would see in the form of impressive real GDP growth or productivity improvements—this would usually mean that firms will find it hard to make good on their investments, and governments will find their national debts increasingly hard to manage. This is exactly what we are seeing.

As I said above the weird thing about this situation is we actually have an easy-ish solution. Commit to meeting the inflation target, making up the deficit of the past few years and targeting a level path of inflation (or total income) in the future. That means that if the ECB makes a mistake and 'undershoots' its target, it doesn't allow this to distort the economy but does a little extra inflation in the next few months; if the ECB 'overshoots' it does a little less. This is not baleful central bank 'intervention' or 'disortion'—the distortion was letting the rules of the game depart so far from those they signed all of their contracts expecting.

The alternative is a 'lost quarter century' of stagnation while everyone slowly adjusts to the new monetary arrangements they have been hit with.

George Monbiot doesn't quite get this competition thing

We've George Monbiot telling us all that this market thing, this rampant individualism, means that we all no longer cooperate with each other. Sadly, this shows a terrible misunderstanding of what markets actually are. They are, of course, a method by which humans cooperate with other humans. Competition is simply the method by which we decide who to cooperate with:

Yes, factories have closed, people travel by car instead of buses, use YouTube rather than the cinema. But these shifts alone fail to explain the speed of our social collapse. These structural changes have been accompanied by a life-denying ideology, which enforces and celebrates our social isolation. The war of every man against every man – competition and individualism, in other words – is the religion of our time, justified by a mythology of lone rangers, sole traders, self-starters, self-made men and women, going it alone. For the most social of creatures, who cannot prosper without love, there is no such thing as society, only heroic individualism. What counts is to win. The rest is collateral damage.

If I grow the pears, you grow the apples, then Bob and Jim make the cider and perry from them, then we sell some and drink the rest, are we competing against each other here? Or are we cooperating over the specialisation and division of labour and then trading in the resultant production? It is the latter of course: competition only comes in when we're deciding whether it's you growing the apples for this enterprise or Charlie in the next orchard over. The same with Bob and Jim: there might be competition to see whether it should be Bill and Johnny making that alcoholic nectar, but the end result is still that competition is how we decide who to cooperate with, the actual activities in the market, in the production cycle, being cooperation.

This same is true if it's Danny in Taiwan making the chips, Yue in China assembling them and Rupert in Cambridge writing the operating system that makes the smartphone work. The market is still the method by which we coordinate cooperation among human beings.

Over and above that misunderstanding there is also this from George:

This is the Age of Loneliness.

Well, yes, intellectual who lives in the depths of rural Wales thinks loneliness is an important phenomenon. There is a reason why the intelligentsia of every society tends to cluster in the cities. We might even identify a little bit of excessive projection from the personal to the general in this screed.

It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble

It's what you know for sure than ain't so that does. And Mark Twain's observation has a great deal to tell us about how and why economic policy is so often so bad. For it's not just the politicians who are deeply misguided as to what the facts of the situation are: we the citizenry can be alarmingly inaccurate in the things we believe about the economy. As Tim Taylor points out:

There's an old saying often attributed to Daniel Patrick Moynihan that "Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but not to their own facts." In public opinion surveys, of course, people are offered a chance to assert facts that reflect their own frame of mind. For example, Social Security is popular, while foreign aid is not, and therefore people (wishfully) hold the opinion that we must not be spending too much on Social Security, but are spending a lot on foreign aid that could cut with little domestic pain. But it's obviously tricky to have a productive social discussion about economic issues when there is little agreement on central facts.

Very much the same holds true in the UK: people overestimate the unemployment rate, how much is spent on overseas aid, underestimate how much pensions cost and so on. And then of course there's the very slightly more tricky things that we should be able to agree upon but generally don't: a higher minimum wage reduces the number of jobs, rent control is the best way of destroying urban housing short of aerial bombardment and so on. We even have our own version of that Moynihan quote, comment is free but facts are sacred.

Would that public discourse, the setting of public policy, took place within the boundaries of those facts rather than being misinformed by what people are sure is true but just ain't so.

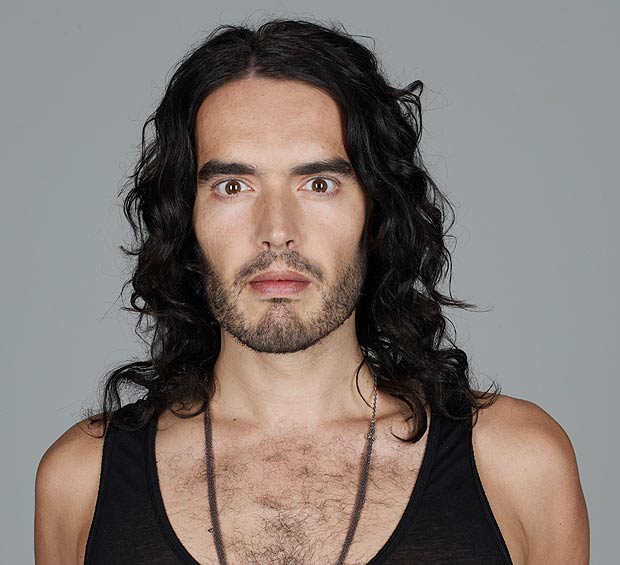

Something a little odd in Russell Brand's Revolution

We clearly weren't going to get a deep and complex understanding of economics in Russell Brand's little manifesto for a better world, Revolution. Nor, given that his amanuensis appears to be Johan Hari, should we have expected one. But to get the result of one of the more famous psychological/economic experiments the wrong way around is still pretty impressive:

Slingerland explained, between great frothing gobfuls of munched hazelnut, that this inherent sense of fairness is found in humans everywhere, but that studies show that it’s less pronounced in environments where people are exposed to a lot of marketing. “Capitalist, consumer culture inures us to unfairness,” he said. That made me angry.

The anger there is justified. For all of the experimental evidence points entirely the other way, that capitalist, consumer (the two being linked because only this capitalist free marketry has ever produced a society where consumerism is even possible) cultures show vastly increased senses of fairness. It's actually one of the things that makes them work.

In the closely related ultimatum game one player is given some sum of money to split (say, $100). Player one can decide how that split is to work, 50/50 or 99/1 and anything inbetween or the other way, their choice. Player two the decides whether to accept that split at which point both participants get their cut of the cash. If player two rejects the split as being "unfair" then no one gets anything.

The standard results (usually those results come from rather rich Ivy league students playing each other as that's the group that professors tend to have access to) indicate that there is an inherent "fairness" bug built into human behaviour. If player one moves to something like a 70/30 split (and it's worth noting that no one ever offers better than 50/50, there's just no 40/60 splits out there) then the odds of the deal being rejected soar.

People really are willing to punish themselves to enforce some idea of fairness.

And that's where the usual analysis stops: people are fair so capitalism Yah! Boo! Sucks!

However, some researchers have started to play this very same game with people who are not rather rich Ivy League students. And the results in non-capitalist, non-market and non-consumer societies are very different. Here people act more like the conventional game theory would expect: when offered a 98/2 split player two will take it. Heck, it's 2 free dollars, why not? People in non-capitalist and non-consumer cultures do not seem willing to pay a price themselves to punish perceived unfairness.

All of which shows us that capitalist consumerism brings with it (or, as certain researchers posit, the behavioural change is what makes capitalist and free market societies work, that understanding about the quid pro quo) a heightened sense of fairness and equity, not a lowered one.

As I say, we'd not expect Brand (or Hari) to get their economics correct but to get it 180 degrees the wrong way around is still pretty impressive.

Austrian fanatics ruin it for the rest of us

The Adam Smith Institute has long been associated with the Austrian school of economics. There is a picture of Friedrich Hayek on the wall. Our Director, Dr. Eamonn Butler, has written Austrian Economics: A Primer and books on Hayek and Ludwig von Mises. With respect to myself, I am personally friendly with, and/or heavily influenced by Austrian-leaning economists including George Selgin, Anthony J. Evans, Emily Skarbek, Mark Pennington, Kevin Dowd, David Skarbek, Adam Martin and dozens of others. I own about 15 books by Ludwig von Mises. I went to a Man, Economy & State reading group. I am still technically a moderator on the Ludwig von Mises Institute forums. My very first post for this blog was on the Austrian theory of the business cycle.

Smart Austrian economists have done, and still do, lots of important work. I personally think that Israel Kirzner deserves a Nobel prize for his work on entrepreneurship. I don't think Austrians are deserving of the hit pieces that some less pleasant members of the mainstream level against them. But there is a genre of commentary, particularly seen below the fold in economics blog comment sections, whose contentless, nebulous, impossible-to-completely-eradicate nonsense unfairly tars all Austrian-influenced economists.

A recent example was left on Sam's post on NGDP targeting, and many of those in the genre follow a similar pattern. Here I will focus on one issue: the dismissal of Sam's argument as 'Keynesian', because it includes non-Austrian ideas. This is probably the worst and most annoying flaw internet Austrians display. Not all non-Austrian arguments are Keynesian.

There is nothing a Keynesian or New Keynesian or post-Keynesian would recognise as Keynesian in Sam's post: he doesn't talk about natural interest rates*, he doesn't talk about marginal propensities of consumption, he doesn't talk about multipliers, he doesn't advocate fiscal stimulus, he doesn't mention a paradox of thrift or liquidity trap. He uses the equation of exchange, which is about as non-Keynesian as you can get!

And many if not most (macro)economists through history have been neither Austrian nor Keynesian, including prominent figures such as Irving Fisher, Milton Friedman, Robert Lucas, and Ralph Hawtrey. At least two schools of thought are neither Keynesian nor Austrian: New Classical/freshwater macro, and monetarist/Chicago school macro. And these schools don't just differ from Keynesianism, they actively and vigorously oppose it on a host of important issues.

It just doesn't do to call all non-Austrian economists 'Keynesians'. It's inaccurate and it's irritating and it's idiotic. Economists have worried about demand-side or money-demand-caused recessions before Keynes and they've worried about them since without accepting any or all of his solutions.

What's more, there is no reason why being an Austrian economist should preclude one from interest in any of these approaches—something smart Austrian and Austrian-influenced economists like Hayek and Selgin have not shied away from. Hayek warned of the dangers of a 'secondary depression' caused by monetary contraction after the real shock involved in the Austrian theory. Austrian fanatics ruin it for everyone.

*George Selgin points out in the comments that natural interest rate ideas predate Keynes and are important in Austrian theory.

Bad arguments against selling the government's stake in Eurostar

The same bad arguments crop up again and again in political debates. The government is now looking, as it planned in the 2013 Autumn Statement, to sell off its 40% stake in Eurostar, for about £300m, as part of a general plan to get £20bn from privatising assets. In response, one popular argument is that the government is throwing away an asset, part of the 'family silver' that generates a few million quid each year for the exchequer.

But as I have repeatedly argued, this makes no sense. Instead of holding £300m in railway shares it can pay down debt, earning (approximately) the same risk-adjusted return. Even if they gave it away, they could just tax the returns from the private sector. As I said before:

A firm, in doing business, puts capital to use. It uses a mix of physical and human capital and devotes it toward achieving tasks in order, usually, to turn a profit. From this capital you get a return. Train Operating Company margins average about 4% over the last ten years. The average company got more like 10%. FTSE100 companies seem to enjoy higher returns. Of course, operating profits are not share returns, but they tell more or less the same story. The extra couple dozen billion the government would need to spend on trains could equally be spent on equities or anywhere else for more or less the same risk-adjusted return. The return they got here could be put into trains.

If the government returns that couple dozen billion to the population at large, the government can tax the income that the private citizens make on the wealth, at a glance dealing with the problems of governments holding wealth—principally: they are not very good at picking winners. Or they could pay off debt and reduce their repayment costs—since the risk-adjusted return of gilts is priced in just the same way as other assets.

This is just a general application of the problem of government's holding assets, which I have written about at length:

So maybe the government should hold some wealth, I can see the arguments for and I can imagine some arguments against. But if it holds wealth it ought hold assets as broadly as possible: because it’s not placed to take gambles on particular assets; because doing so may distort markets directly; because holding assets takes them off the market and reduces allocative efficiency; and because holding particular assets may distort the incentives facing policymakers. Thus we should praise Gordon Brown for selling off gold just as we should praise Vince Cable and George Osborne for selling off the Royal Mail.

To be fair, in this case the French & Belgian state stakes are going to stop this 'privatisation' leading to big allocative efficiency gains, but these widely-made arguments are still extremely unconvincing.

This is a very strange argument against foreign aid

And it's coming from a very strange place, too, the Jubilee Debt Campaign. These are the people who tell us that we should just write off the debts of the poor of the world, both countries and people. At times and in places they've certainly got a point but this is still a very strange argument:

A sharp rise in lending to the world’s poorest countries will leave them with crippling debt payments over the next decade, a few years after many had loans written off, a report has warned.The Jubilee Debt Campaign said as many as two-thirds of the 43 developing countries it analysed could suffer large increases in the share of government income spent on debt payments over the next decade.

Coinciding with the World Bank’s annual meeting in Washington, the anti-poverty campaigners accuse the international lender and other public bodies of “leading the lending boom” to poor countries without checking how repaying debts will divert resources from cutting poverty.

What they think they're saying is that we shouldn't be lending these people this money, we should just be giving it to them in the form of grants. What they're actually saying is that the money shouldn't be going there at all. For look at what they do say: money is going to these poor countries, yes, but the returns from it going there aren't enough to pay the interest bill on that money.

Now, we can play all Teenage Trot and shout that so what? But we should perhaps be adult and remind ourselves that prices are information. These loans are already at concessionary interest rates meaning that risk is pretty much disregarded. All that is included in the rate is the time value of money. And if investment in these countries cannot even cover that time value of money then this sort of spending is a really bad thing to be doing. It's value destruction upon a global scale.

Converting it all to grants doesn't change this: investing money in something that cannot even cover the cost of simple interest (not even risk adjusted interest!) is still that value destruction, whether we charge the interest or not.

No, this does not mean that we here think that the poor should be left to fester in their squalor. The above though does mean that simply shipping off money isn't the right way to be going about things: for as we can see no value is being added. The correct answer is that emergency aid should still exist: doesn't really matter where you get your moral precepts from feeding the starving is still worthwhile. However, that developmental aid, that aid that is being wasted simply because it cannot even pay back its own value, should perhaps cease. To be replaced by the one thing that has lifted hundreds of millions, if not billions, up out of poverty in recent decades. We should be buying the things made by poor people in poor countries. And the best thing we could do for those poor is to tear down the barriers we still impose upon ourselves stopping us from doing ever yet more of that.

Markets like women too

Last week I wrote about how markets militate against racism. It's a basic and over-worn point, but it seems to be forgotten regularly anyway. Here I shall make the same point, but with respect to women. It's a common view that women are paid less than men on average, even after you account for hours, experience, qualifications, industry, risks, pleasantness of job and so on (though they do account for a very large fraction of the gap).

But there are a few other factors that studies have only started looking into recently. One of those is exit. Women often exit the labour force earlier than men, trade down to more flexible or part-time jobs that don't pay as well. It might well be said that this is the product of socially constructed expectations about what different genders are expected to do and how they are expected to structure their lives—with one gender still doing more work outside the house and one still doing more inside.

But even if this is true, it is important to stress that this 'discrimination', which certainly doesn't seem to result in lower happiness for women, happens at the level of upbringing, schooling, and so on rather than at the level of employment. Firms are not to blame and indeed, recent research suggests firms are actually pretty pro-women.

For example, "Gender Differences in Executive Compensation and Job Mobility", published in the Journal of Labour Economics in 2012 (up-to-date abstract here, full working paper pdf here) finds that if you control for background (i.e. skills and talent) and exit (i.e. women staying in the workforce) women earn more than men and get more aggressively promoted than men.

Fewer women than men become executive managers. They earn less over their careers, hold more junior positions, and exit the occupation at a faster rate. We compiled a large panel data set on executives and formed a career hierarchy to analyze mobility and compensation rates. We find that, controlling for executive rank and background, women earn higher compensation than men, experience more income uncertainty, and are promoted more quickly. Amongst survivors, being female increases the chance of becoming CEO. Hence, the unconditional gender pay gap and job-rank differences are primarily attributable to female executives exiting at higher rates than men in an occupation where survival is rewarded with promotion and higher compensation.

Another paper, from July this year, finds that reservation wages (the lowest amount a person will take to do the job rather than remaining unemployed and taking nothing) explain the entirety of the gender wage gap that remains after you control for personal and job characteristics. This suggests, again, that the discrimination that is happening (if it is happening) is not coming from markets.

The economic literature typically finds a persistent wage gap between men and women. In this paper, based on a sample of newly unemployed persons seeking work in Germany, we find that the gender wage gap disappears once we control for reservation wages in a wage decomposition exercise. Despite a concern with reservation wages being potentially endogenous, we believe that the exploratory results in our paper can help one better understand what the driving forces are behind the gender wage gap. As the gender gap in actual wages appears to mirror the gender gap in reservation wages, there is a clear need to better understand why there are gender differences in the way reservation wages are set in the first place. Whereas a gender gap in actual wages could reflect either productivity differences or discrimination, a gender gap in reservation wages essentially reflects either productivity differences or differing expectations.

This just adds to a burgeoning literature finding that the reason men and women have different outcomes in labour markets is that they differ systematically in job-relevant ways. For example, men in the Netherlands systematically choose more competitive academic tracks. Even very narrow estimates of the risk-tolerance gap between men and women estimates it at about one standard deviation (implying the male and female distributions overlap 80%).

Again, this does not imply there is no discrimination in society—it just shows that it's not corporations, firms, companies, businesses, start-ups, market organisations who are doing it.