There is no such thing as a gender pay gap

Actually, there is a gender pay gap, but the entirety of it is determined by 'legitimate' factors—things which make men's and women's labour different. As well as women having jobs they rate as more pleasant, and jobs that are objectively less risky, as well as doing more part-time work, women leave the labour market during crucial years, setting them substantially back in labour market terms. That is, the gap comes down to women's choices.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, since childcare seems to contribute to mothers' well-being and happiness, and looking after children is certainly not an unimportant task. But it implies that, whether or not society as a whole, through schools, culture, upbringing and so on, is the reason women do most of the labour in the home and in child rearing, firms are not discriminating against women.

Two new papers add to the formidable base of evidence for this conclusion. In "The Gender Pay Gap Across Countries: A Human Capital Approach", authors Solomon W. Polachek and Jun Xiang take a lifetime labour supply approach. They find that the wage gap increases with women's fertility, the size of the average age gap between men and women at marriage, and the top marginal tax rate, all things which affect women's total labour supply over their lives and at crucial points. (It decreases with the prevalence of collective bargaining).

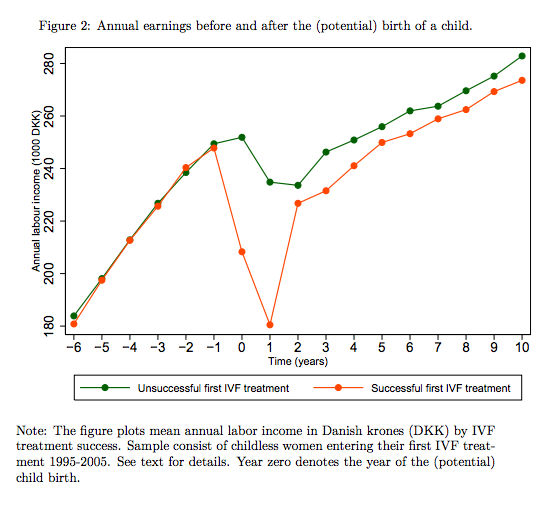

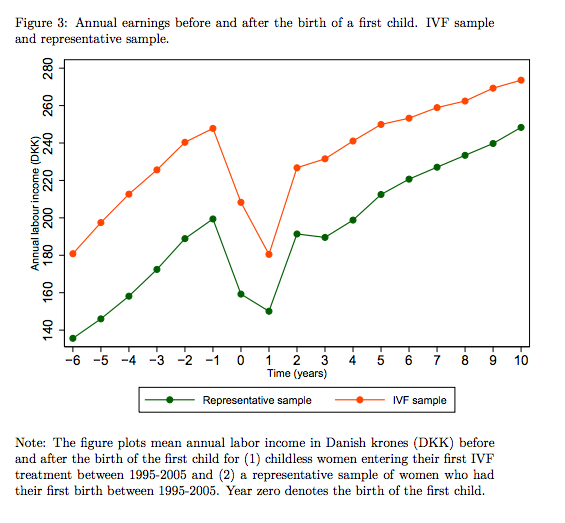

An even more interesting approach came in "Fertility Effects on Female Labor Supply: IV Evidence from IVF Treatments" by Petter Lundborg, Erik Plug and Astrid Würtz Rasmussen. To abstract from the possibility that women who decide to have kids have systematically different characteristics affecting what kind of career they'd have, they look at those who try to have children via In-Vitro Fertilisation (IVF):

This paper introduces a new IV strategy based on IVF induced fertility variation in childless families to estimate the causal effect of having children on female labor supply using IVF treated women in Denmark. Because observed chances of IVF success do not depend on labor market histories, IVF treatment success provides a plausible instrument for childbearing. Our IV estimates indicate that fertility effects are: (a) negative, large and long lasting; (b) much stronger at the extensive margin than at the intensive margin; and (c) similar for mothers, not treated with IVF, which suggests that IVF findings have a wider generalizability.

The results are pretty clear. Women are on a steady upward trajectory, likely in line with comparable men (as seen in previous studies). They then decide to take time out to have and raise children, and never make it back to their previous trend-line, perhaps moving to more flexible work or less demanding jobs. Even those who go back to similar careers are far behind in experience and have to catch up with movements they have missed.

So, while there might be such thing as a gender wage gap, the alternative is completely changing how children are raised in society, and while this would certainly have the potential to raise measured output, it may not necessarily raise total social welfare.

We've actually tried negative income taxes, and they seem to work

The latest issue of Chicago magazine has a great piece on the 1970s experiments with the Negative Income Tax (NIT) including in the deprived city of Gary, Indiana (famous for being the birthplace of the Jacksons). Inspired by Milton Friedman, and in an effort to reduce time, effort and effort spent administering welfare as well as stigma in receiving it, some of the poorest residents of Gary and four other poor areas received cash in randomised controlled experiments.

A lot of research was done into the treatment groups in Gary and across the other NIT experiments.

One study found that kids born to mothers in the treatment group had birth weights 0.3-1.2lb higher. Another found significant and substantial improvements in reading scores for children in treated families. And what's more, kids whose families had been in the programme for a number of years performed significantly better than those in it for a shorter time. School performance also increased significantly across a wide variety of metrics for early-grade students in a rural experiment in North Carolina, although the effect did not appear in the other major experiment, in rural Iowa.

It's not clear exactly where this effect came from, but the most plausible source is probably better nutrition and spending the extra money on housing in better areas. Most of the evidence suggests that recipients did not spend their windfall on expensive consumption goods.

There were no overall robust effects on marital stability, but this was misreported, and the mistaken belief that the NIT had led to black families breaking up was a significant factor in killing the proposal as a political possibility under Richard Nixon.

However, as well as the effects seen, the experiments seemed to find that the income effect—having more money overall—outweighed the substitution effect—lower and more predictable effective marginal tax rates making it more attractive to work—especially when it came to women. A glance at the table below makes this clear.

But it's possible to conclude that the fall in the amount of labour those getting the NIT supply (something like 5% for the poor groups studied, and around 2% estimated for the population as a whole) is quite small, and within the bounds of what we'd be willing to accept to substantially reduce poverty.

What's more, there are countervailing factors. One issue is the level of the guaranteed income. Some of the families received were guaranteed an income 150% of the poverty line. With a benefit level closer to the existing system, merely structured more clearly and predictably, we might expect a weaker or even positive response (although we alleviate less poverty).

A second issue is the long-term response. If the negative income can counteract large environmental problems, allowing families to move away from pollution and feed their kids better and achieve more in school, we might see these people enjoy improved long-term life outcomes. Even looking at things from a narrow labour supply perspective, we know that more educated and more intelligent people supply more labour over their lives, so the long-term effect may be neutral.

(Tables sourced from Widerquist (2005))

Gordon Tullock: a great economist with no degree in economics

Following this approach, Tullock, Buchanan and fellow thinkers in the 'Virginia School', which focused on real world political institutions, realised that democratic processes were too often a very messy, exploitative and irrational way to make choices. They concluded that we should not be dewy-eyed about government decision making, and that we should limit it only to the things that are both crucial to do and simply cannot be done any other way.

Buchanan, in particular, emphasised the need for constitutional restraints so as to curb the exploitation of minorities by majorities, or of the silent majority by activist interest groups. On that front, Tullock will be particularly remembered for his delineation of the concept of Rent Seeking. The concept, and even the term, predated that work, but his contribution was to show how the cost of lobbying for government perks and privileges was economically inefficient and politically corrupt. He observed – the 'Tullock Paradox' – that the cost of rent seeking was often very low in proportion to the potential payoffs. A little lobbying can win potentially massive privileges (such as 'quality' regulation that effectively keeps out the competition). So it is no surprise that the lobbying industry has grown so large. And the more that government's range, power and tax take expands, the larger are the potential gains.

Many of Tullock's friends and colleagues were disappointed that he did not share in James M Buchanan's 1986 Nobel Prize. He never complained about it; and he will still be remembered with respect and affection.

Free banking in 19th century Switzerland

RePEc is a wonderful service, provided like the fantastically useful FRED by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. It has feeds on twitter and via RSS, which are one of the best ways of keeping up with new research papers on economics, provided as full pdf files—all for free. Occasionally, their feeds deliver older papers, which have presumably been scanned and indexed online in the database for the first time. A recent example was "The Competitive Issue of Paper Money in Switzerland After the Liberal Revolutions in the 19th Century" by Ernst Juerg Weber, an economist who was then, in 1990, and is still now, working at the University of Western Australia. I had never heard of him but his papers all look extremely interesting. This one is no exception, and it tells of how banking was completely deregulated during the early 19th century in Switzerland, and how it worked extremely successfully:

The main finding of this paper is that competition provided a stable monetary system in Switzerland in which the purchasing power of bank notes equaled that of specie and only one bank failed. The Swiss banks did not over issue bank notes because there was no demand for depreciating notes in the competitive Swiss monetary system. Each bank faced a real demand for bank notes that depended on the usefulness of those notes in commercial transactions. And the marginal revenue of inflating was negative for each bank because depreciating notes impose information costs on their users and people could easily substitute notes. In contrast, modern central banks can inflate at a profit because (i) they have the exclusive right to issue currency and (ii) currency substitution is limited by legal tender laws and -if necessary -by exchange controls. The Swiss monetary system was also stable in the sense that rising costs prevented a central-bank-like monopoly by a single issuer.

Liberals won a short civil war in 1848 then, in control of the federal government, removed restrictions on the free movement of goods, capital and people between cantons. This included allowing private banks to issue the newly-unified currency, the Swiss Franc.

There were no legal tender laws or exchange controls, and by 1880 there was one note issuing bank per 80,000 people, or 36 in total. Even though cantonal banks had regulatory and tax advantages, commercial note-issuing banks were able to outcompete them

Banks worked like any other business, with free entry into the note issuing business determined by whether they could offer notes that people found useful in transactions. Savings banks stayed out of the note business because they could not profit from issuing them.

However during the 1860s and 1870s more the democratic factions were in the ascendancy and started rolling bank liberal provisions, for example setting up subsidised and guaranteed cantonal note-issuing banks and heavily regulating note issue. By 1881 the Swiss free banking era was over despite its success.

In general free banking is a strange issue, because it seems like advocates have done a huge amount of work showing its successes and highlighting the failures of alternative systems. But opponents have mostly ignored all of this and seemingly work on entirely unchallenged views of one free banking system (the USA 1837-1862), acquired apparently by osmosis. If free banking wouldn't work in the modern era, then opponents need to do a lot more to explain why.

Deflation in the Eurozone is not good deflation

ASI Senior Fellow Anthony J. Evans has a very good new piece on the Cobden Centre blog. First he notes how Austrian economists have been able to say interesting things about deflation that others have missed:

As inflation rates continue to fall across the Eurozone one might expect Austrian economists to rejoice. After all, inflation reduces our purchasing power and acts as a hidden form of taxation. Failure to control inflation caused some of the greatest social and political disturbances of the twentieth century, and attempts to centrally plan the monetary system are destined to failure. George Selgin’s “Less than Zero” is the seminal account of how deflation can be beneficial, and why central banks should be willing to tolerate it.

But he goes on to point out that this 'good deflation' is typified by rising real incomes, as it has come through productivity improvements. If we don't see rising real incomes, then we're not seeing good deflation. If we are seeing bad deflation then we risk sustained recession and depression, as inflexible wages are forced to bear the burden of adjustment:

Austrians are loathe to advocate monetary activism and for good reason. But the goal of monetary policy is not inactivism, but neutrality. The issue comes down to the costs of adjustment. If aggregate demand remains at 1% then people will adjust their expectations, prices will adjust, and output will return to normal. During the Great Depression Hayek advocated this path, even though he recognised that prices take time to adjust, and whilst they do so unemployment would rise. His reasoning was that increasing the load on price adjustments will increase their flexibility. In a time of chronic wage and price inflexibility it was a moment to bust the unions. However he later came round to the idea that those costs were too high. The collateral damage of using a downturn to put more emphasis on nominal wage adjustments was unfair. For the mass unemployed, nominal wage rigidities isn’t their fault. So instead of placing the burden on wage adjustments, central banks have the option of maintaining a certain level of total income. This avoids the necessity of a nominal wage adjustment, in part because inflation allows real wages to adjust.

The whole piece is very good, and consonant with what I have been trying to say since the third dip of the ongoing Eurozone crisis.

Small steps towards a much better world

Changing policy, ideology, popular opinion, media narratives and so on can be very hard. Changing social norms and culture is even more difficult. Thus, when a small technological innovation comes along that can substantially improve things, even in a small area, it really lifts my heart as it seems 'easy' and 'free'. A recent example is the introduction of tablet computers to Florida restaurant inspections (according to a new paper in The RAND Journal of Economics). Getting rid of corruption, making people more conscientious and diligent and designing incentive systems that improve things are all very hard, and that's why we at the ASI often make the case for tried and true robust mechanisms. But the paper, from authors Ginger Zhe Jin and Jungmin Lee found that this tiny change made a sizeable difference:

In this article, we show that a small innovation in inspection technology can make substantial differences in inspection outcomes. For restaurant hygiene inspections, the state of Florida has introduced a handheld electronic device, the portable digital assistant (PDA), which reminds inspectors of about 1,000 potential violations that may be checked for. Using inspection records from July 2003 to June 2009, we find that the adoption of PDA led to 11% more detected violations and subsequently, restaurants may have gradually increased their compliance efforts. We also find that PDA use is significantly correlated with a reduction in restaurant-related foodborne disease outbreaks.

Enjoy a chart of the finding below, and a full pdf of the working paper here.

What Robert Peston gets wrong about QE

I don't usually read Robert Peston, now the BBC's economics editor, but I came across this piece he wrote for their website on the end of the ongoing US quantitative easing (QE) programme. Here he makes the case, overall, that even though QE did not cause hyperinflation (yet!) it could still prove 'toxic' because it 'inflates the price of assets beyond what could be justified by the underlying strength of the economy'. Basically every line of the piece includes something that I could dispute, but I will try and focus on the most important issues. The first problem is that Peston takes a hardline 'creditist' view that not only is QE mainly supposed to help the economy through raising debt/lending, but by raising it in specific, centrally-planned areas (e.g. housing). When we find that QE barely affected lending, it seems to Peston that it failed. But QE does not raise lending to raise economic activity—QE raises economic activity through other channels, which may lead to more lending depending on the preferences of firms and households.

In his 2013 paper 'Was there ever a bank lending channel?' Nobel prizewinner Eugene Fama puts paid to this view. He points out that financial firms hold portfolios of real assets based on their preferences and their guesses about the future. QE can only change these preferences and guesses indirectly, by changing nominal or real variables in the economy. For example, extra QE might reduce the chance of a financial collapse, making riskier assets less unattractive. But when central banks buy bonds investors find themselves holding portfolios not exactly in line with their preferences and they 'rebalance' towards holding the balance of assets they want: cash, equities, bonds, gilts and so on. This is predicted by our basic expected-profit-maximising model and reliably seen in the empirical data too. It's good because it implies that monetary policy can work towards neutrality.

This doesn't mean Peston is right to be sceptical about the benefits of QE. QE has worked—according to a recent Bank of England paper buying gilts worth 1% of GDP led to .16% extra real GDP and .3% extra inflation in the UK (2009-2013), with even better results for the USA. The point is that it works through other channels—principally by convincing markets that the central bank is serious about trying to achieve its inflation target or even go above its inflation target when times are particularly hard. This is not an isolated result.

The second issue is that Peston claims QE isn't money creation:

Because what has been really striking about QE is that it was popularly dubbed as money creation, but it hasn't really been that. If it had been proper money creation, with cash going into the pockets of people or the coffers of businesses, it might have sparked serious and substantial increases in economic activity, which would have led to much bigger investment in real productive capital. And in those circumstances, the underlying growth rate of the UK and US economies might have increased meaningfully.

But in today's economy, especially in the UK and Europe, money creation is much more about how much commercial banks lend than how many bonds are bought from investors by central banks. The connection between QE and either the supply of bank credit or the demand for bank credit is tenuous.

That is not to say there is no connection. But the evidence of the UK, for example, is that £375bn of quantitative easing did nothing to stop banks shrinking their balance sheets: banks had a too-powerful incentive to shrink and strengthen themselves after the great crash of 2008; businesses and consumers were too fed up to borrow, even with the stimulus of cheap credit.

This is extremely misleading and confused. He suggests that printing cash and handing it out would boost the 'underlying' growth rate, which is nonsense—the 'underlying' growth rate is driven by supply-side factors. He claims that money creation is identical with credit creation, when they are separate things, and he has already pointed out that creating money doesn't always lead to more credit. We have already seen how credit is not the way QE affects growth, despite what economic journalists like Peston seem to unendingly tell us. Indeed, it seems quite clear that the great recession caused the credit crunch, rather than the other way round.

His ending few paragraphs are yet stranger:

But the fundamental problem with QE is that the money created by central banks leaked out all over the place, and ended up having all sorts of unexpected and unwanted effects. When launched it was billed as a big, bold and imaginative way of restarting the global economy after the 2008 crash. It probably helped prevent the Great Recession being deeper and longer. But by inflating the price of assets beyond what could be justified by the underlying strength of the economy, it may sown the seeds of the next great markets disaster.

It's not clear at all why Peston thinks that QE would inflate asset prices beyond what could be justified. I've written at length about this before. The money a trader gets from selling a gilt to the Bank of England is completely fungible with all their other money. There is no reason to expect they will put this money in an envelope and save it for a special occasion. They try and hold the same portfolio of assets as they did before. Through various channels (including equity prices -> investment) QE raises inflation and real GDP and surprise surprise these are exactly the things that asset prices should care about.

Now Screening: A tragic drama of the London Living Wage

After months of campaigning, no less than 13 strikes and support from the likes of Ken Loach and Eric Cantona, Brixton Ritzy Picturehouse cinema staff have finally secured a commitment to be paid the London Living Wage.

Unfortunately, this means that a quarter of the payroll is now facing the sack:

Picturehouse Cinemas said that the cost of increasing basic wages at the Ritzy Cinema in Brixton to £8.80 an hour would be absorbed by reducing the number of staff by at least 20, with a redundancy programme starting next month.

Two management posts will be axed along with eight supervisors, three technical staff and other front-of-house workers from its workforce of 93.

Naturally, Owen Jones has some insight into the situation:

The message appears transparent: if you fight for a living wage and workers’ rights, then you face the sack. Or we will crush you if you dare to stand up for yourselves.

In fact, the message is even more clear than this. If wages are set higher than it is productive or profitable to do so, the firm will have to account for the cost in other ways. We often talk about the unintended consequences of things like price controls and wage demands, but in this case the consequence of such a pay rise was pretty damn clear. As the Picturehouse explains:

During the negotiation process it was discussed that the amount of income available to distribute to staff would not be increasing, and that the consequence of such levels of increase to pay rates would be fewer people with more highly paid jobs.

The Ritzy previously paid staff £7.53 an hour with a £1/hr customer satisfaction bonus—far higher than the National Minimum Wage of £6.31, whilst union pay negotiators pointed out the Ritzy staff do actually like working there. This makes the idea that job cuts are bitter, tit-for-tat 'payback' seem rather perverse. Indeed, to make something sound so heartless and threatening when it is basically Econ 101 is bordering on the petulant.

In a perfect world low pay simply would not be an issue. In the meantime if employers can afford to give the LLW (or can benefit enough from the PR!), then fantastic. But paying 93 staff £8.80 an hour is no small commitment, and unfortunately pushing company policy in one direction all too often means something's got to give elsewhere.

Whilst the effects of a National Minimum Wage aren't always easy to spot, this is a concrete example of the London Living Wage actively putting Londoners out of a living. In personal experience Ritzy employees are friendly, intelligent and helpful, but sadly that's no guarantee of them getting another job. And if unions continue to push for the LLW in such an aggressive manner, this is unlikely to be the only casualty.

Curzon cinemas have just announced that they will pay their staff the LLW, even though it is loss-making. They say they hope that the cost will become self-financing through the better quality of work which paying people more will achieve. It will be interesting to see if that's the case. In any case—grab the popcorn, this show's going to get interesting...

Slow economic growth is the new normal apparently

So Gavyn Davies tells us over in the Financial Times:

The results (Graph 1) show an extremely persistent slowdown in long run growth rates since the 1970s, not a sudden decline after 2008. This looks more persistent for the G7 as a whole than it does for individual countries, where there is more variation in the pattern through time.Averaged across the G7, the slowdown can be traced to trend declines in both population growth and (especially) labour productivity growth, which together have resulted in a halving in long run GDP growth from over 4 per cent in 1970 to 2 per cent now.

Obviously, for the sake of our grandchildren, we'd like to work out why there has been this growth slowdown. Fortunately, there's an answer to that:

But run the numbers yourself–and prepare for a shock. If the U.S. economy had grown an extra 2% per year since 1949, 2014′s GDP would be about $58 trillion, not $17 trillion. So says a study called “Federal Regulation and Aggregate Economic Growth,” published in 2013 by the Journal of Economic Growth. More than taxes, it’s been runaway federal regulation that’s crimped U.S. growth by the year and utterly smashed it over two generations.

A version of that paper can be found here.

No one is saying that there's not a case for regulation: there's always a case for every regulation, obviously. There's also a smaller class of regulations where the case made for it is valid: where it's worth whatever growth we give up in having the regulation in order to avoid whatever peril it is that the regulation protects us from.

But this doesn't mean that all regulations have a valid case in their favour: and one darn good reason against many of them is that we're giving up too much economic growth as a result of the cumulative impact of all of those regulations.

If we want swifter economic growth, something we do want for the sake of those grandkiddies, then we do need to cut back on the regulatory state. Hopefully before all growth at all gets strangled by the ever growing thickets of them.

Markets involve substantial fairness

I have been writing recently about how market mechanisms work against taste-based (i.e. objectionable) discrimination on grounds of race and sex. A while ago, I wrote how, even if we think that people should not be punished with bad lives for being unlucky with their upbringing or talents, we should favour some wealth and income inequality in many situations so as to achieve more overall justice.

For example, if some choose to take more leisure instead of income, then it would not be just (on egalitarian grounds) to make sure their monetary income or wealth were equal—leisure is a sort of income. Similarly, it would not be just for people with more pleasant, safe or satisfying jobs to earn as much as those with less pleasant, more risky, or less interesting jobs (on egalitarian grounds).

There is one school of thought that understands and agrees with these caveat to equality. They may even note that teachers, who are respected and admired by society, and whose jobs are largely pleasant, satisfying and risk-free should not justly earn as much as despised unhappy bankers. But in the real world they see examples where people seem to have jobs that are high in pay and low in other benefits—boring or risky or low-status. Are markets failing to compensate people in pecuniary terms for the non-pecuniary costs of their job?

According to a new paper, they are not:

We use data on twins matched to register-based information on earnings to examine the long-standing puzzle of non-existent compensating wage differentials. The use of twin data allows us to remove otherwise unobserved productivity differences that were the prominent reason for estimation bias in the earlier studies. Using twin differences we find evidence for positive compensation of adverse working conditions in the labor market.

The authors look at twins to control for 'unobservable' factors about the person—basically their productivity and how employable they are—and find that workers are paid more for doing less desirable jobs. Though it often seems like they aren't, this is only because some people (mainly people on early steps of the productivity/human capital ladder without much in the way of experience or skills) are very unproductive. Of two twins, the one with a less pleasant or more risky job gets paid more.

The unique feature of our data is that we are able to estimate specifications that also control for unobservable time-invariant characteristics at the twin pair level (e.g. place of residence, spouse’s occupation, or family situation) and the common wage growth for the twins. We find evidence for positive compensating wage differentials for both monotonous and physical work using the data on MZs (monozygotic, i.e. identical, twins). Assuming that equal ability assumption holds for MZs, the results imply that both twin difference estimates and Difference-in-Differences (combined twin difference – time difference) estimates are unbiased for MZs.

I am perfectly comfortable with arguments that differences in endowments (basically upbringing and inborn talent) mean that there is a case for redistribution between individuals. But it bears repeating that markets, working properly, automatically produce results that in many ways elegantly fulfil the egalitarian concerns of leftist social justice.