Are we innovating less?

According to Huebner (2005) the per capita rate of innovation has been falling steadily since 1873 (it doesn't look quite like that from the chart below, which is just of patents, because patent laws changed a lot during the period). He constructs an index of innovation by looking at independently-created lists of events in the history of science and technology and from US patent records and compares them to the world population.

Woodley (2012), looking at the numbers for a different purpose, compared them with three alternative indices of development, and found that they correlated well with different numbers gathered for different purposes. For example, they correlate highly (with a coefficient of 0.865) with the numbers in Charles Murray's Human Accomplishment, which quantifies contributions to science and arts partly by how much space encyclopaedias devote to particular individuals.

It also correlates 0.853 with Gary (1993)'s separate index, which was computed from Isaac Asimov's Chronology of Science and Discovery. Finally, it correlates with another separate index, created in Woodley (2012), computed from raw numbers in Bryan Bunch & Alexander Hellemans (2004) The History of Science and Technology, and divided only by developed country population numbers in case there is something special about them in creating innovation.

The result seems quite robust, although I am hoping my friend Anton Howes (who has an excellent new blog on the industrial revolution, and is working on a PhD on innovation and the industrial revolution) will construct an even better index. Should we worry?

There are a few reasons for optimism. Firstly, the population is going up, so per capita declines in innovation are being counteracted by there being more people around to innovate. For example, even if Gary (1993) is right in thinking there has been a roughly five-fold decline in per capita innovation in the past 100 years—there has been almost a four-fold increase in population, balancing much of that out. Secondly, some of the innovations we are getting will allow us to raise our IQ—including genetic engineering and iterated embryo selection—and we know that IQ is one important factor in innovation. Thirdly and finally, there are many countries (such as China and India) who have so far been too poor to have many of their population engaged in innovative activities, but who will surely soon be.

To reduce rape in India, legalise porn

In India, there has been uproar amongst the general public and from the media with respect to the alarming frequency of rape across the country. In the four decades leading up to 2012, reported rapeshave increased 900% (alarmingly, some activists claim that 90-99% go unreported). Additionally, in India it is currently legal to watch or possess pornographic material but the distribution, production or publication of such material is illegal. In Anthony D'Amato's (2006) 'Porn Up, Rape Down' (published in the Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series at Northwestern Law School), the abstract reads:

The incidence of rape in the United States has declined 85% in the past 25 years while access to pornography has become freely available to teenagers and adults. The Nixon and Reagan Commissions tried to show that exposure to pornographic materials produced social violence. The reverse may be true: that pornography has reduced social violence.

Of course, it is often presumed by many Indian politicians that Indian society is largely conservative and would not tolerate legalisation of the distribution, production and publication of pornography. This is ironic when we consider that a world-famous book of Indian-origin is the Kama Sutra. Continuing to prioritise the appeasement of conservative facets of Indian society over the safety of women is counterproductive. India certainly has the maturity to see these activities legalised and, given that the recorded incidents of rape has raised serious concerns both within the country and around the world, it is necessary.

Whatever the reason may be for legalised and easily available pornography having a negative impact on rape (and there are more than several competing theories), the fact is that it does have a very strong, negative correlation and if we would like to see a decrease in rape on the subcontinent (both immediately and over time) and anywhere else where it remains illegal, for that matter, it would be best to legalise the distribution, production and publication of pornography immediately.

This would also improve the working conditions and salaries of those workers who are currently exploited in an industry that remains largely underground in the subcontinent, allow social workers to have greater contact with workers in a legal profession, bring in some much needed tax revenue and enable diversion of law enforcement resources from pornographic material to other, more critical issues (such as rape itself).

People of the same trade seldom meet...

It's very rare that new evidence overturns something Adam Smith wrote in the Wealth of Nations or Theory of Moral Sentiments, and a new paper on guilds, to which I was alerted by John Cochrane (read his post on it here), is no exception. Sheilagh Ogilvie's "The Economics of Guilds", in the latest issue of the Journal of Economic Perspectives, lays out a history of European guilds 1000-1800, explains why they rose and fell, and explains how the fit the classic profile of the rent-seeking interest group. In Cochrane's words:

The paper nicely works through all the standard pro-guild and pro-regulation arguments. If you just replace "Guild" with "regulatory agency" it sounds pretty fresh.

Ogilvie shows that guilds neither provided contract enforcement, a guarantee of quality, better training and/or qualifications, or innovation. They eventually declined because globalisation and competition rendered them redundant. She explains that guilds did not exist because they solved market failures but rather because they had obvious, concentrated benefits, and hidden, diffuse costs, and because they could use part of these benefits to bribe authorities.

Guilds were institutions whose total costs were large but were spread over a large number of people—potential entrants, employees, consumers—who faced high transaction costs in resisting a politically entrenched institution. The total benefits of guilds, by contrast, were small, but were concentrated within a small group—guild members, political elites—who faced low costs of organizing alliances to keep them in being. Guilds survived for so long in so many places because of this logic of collective action.

There is nothing new under the sun.

If QE avoided a Depression it doesn't matter if it increased inequality

I’ve just come from a fascinating event with The Spectator’s Fraser Nelson, on his recent Dispatches show, How the Rich Get Richer. In general the show was very good, and it’s extremely refreshing to see someone as thoughtful as Fraser get half an hour of prime time television to discuss poverty in Britain from a broadly free market perspective.

But I did take issue with the show’s treatment of Quantitative Easing (QE). Fraser described this as ‘perhaps the biggest wealth transfer from poor to rich in history’. The evidence for this was the rise in asset prices following QE, particularly in stock markets. Since rich people own assets and poor people don’t, the rich got richer and the poor didn’t.

That’s a common view and I understand it, but I think it’s wrong.

Consider the Great Depression. When the money supply (and hence nominal spending) collapsed in the 1930s, the US economy did too, for reasons outlined in Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s Monetary History of the United States.

Basically, contracts are set in nominal terms, so if nominal spending collapses, you’re left with a musical chairs problem where you have too little money to go round. So people are laid off and firms go bankrupt that would not have done so if money had remained stable across the board. Enormous amounts of wealth were destroyed unnecessarily because the government mismanaged the money supply. (It shouldn't be managing money at all, in my view, but if it is we can at least try to minimise the harm it does.)

Perhaps inequality fell during this period because the rich lost proportionally more than the poor – they had more to lose, basically. But who cares? Everyone became worse off. That’s what matters.

The point of QE since 2008 has been to try and avoid a repeat of the 1930s by boosting the money supply. Its supporters wanted to avoid another massive destruction of wealth that would make everyone much worse off.

Yes, QE boosted stock markets a lot. But there is nothing about QE that meant that banks or other investors would have to invest there – it’s not an ‘injection of cash into stocks’, as some people seem to believe. Stock markets rose because investors reckoned that QE would help avert a much worse Depression, which meant that firms would be (much) more valuable compared to a QE-less world where many of them may have gone bankrupt, or at least taken severe losses, instead.

Yes, that increased inequality because rich people own stocks and poor people don’t. But if everyone would have been worse off without QE, the extra inequality is beside the point. It's people's absolute wellbeing that should matter, if what you're avoiding is a big Depression. You might as well think economic growth is bad because it makes everyone richer, but rich people a little more so.

Of course, it’s an open question whether QE actually did work as intended. Perhaps it made things worse, or did nothing at all. That is a question worth asking and it's not one I can answer. But focusing on whether it increased inequality or not is beside the point – what matters is whether it prevented a Depression.

The Civilisation of Capitalism

In Joseph Schumpeter's (1942) Capitalism, Socialism & Democracy , Chapter 11 is entitled ‘the Civilisation of Capitalism’. There, he argues that the culture fostered by Capitalism has been responsible for the ‘rationalisation’ of society, as we know it. Rather than quoting Schumpeter word-for-word, I’d encourage people to read that short chapter. We can derive inspiration from Schumpeter’s thoughts in making the case for free markets and a free society. Intuitively, one would expect the individual living in a free society to be more intelligent and rational than his counterpart in a hypothetical, centrally planned Utopia (like Plato’s Republic). In a predominantly centrally planned economy, where there is deprivation of civil liberties, choices have already been made on our behalf whereas in a free society, people have more choices. The typical individual in the former will, most likely, be more naïve than his counterpart in a freer society and in the latter more rational. The freer society is, the greater the sphere in which people can develop the appropriate mental faculties for optimising outcomes.

Therefore, total freedom of thought is only really attainable in a free society with free markets. Restricting individuals’ freedoms prevents them from being the best people they can be and therefore prevents the best possible outcome for society as a whole.

It is a fundamental premise in Economics that all economic problems are rooted in the scarcity of resources. In Physics, understanding how to manipulate matter is considered somewhat of a holy grail. A certain depth of understanding with respect to matter would solve the problem of scarcity completely. However, if we indirectly restrict individuals’ thoughts by preventing them from living in a freer society that is conducive to such scientific discovery, we are shooting ourselves in the foot twice since Economics necessarily deals with this problem of scarcity that the other sciences might be able to relieve us of.

In a free society, the enhancement of mental faculties that accompanies increased freedom of thought enables individuals to deal with the problem of scarcity more intelligently, creatively, innovatively and rationally.

Are immigrants dangerous criminals?

Sometimes supporters of strict migration controls criticise my focus on the economics of immigration. They more or less accept that free movement leads to productivity gains, innovation gains, entrepreneurial gains and fiscal gains for the receiving countries, ‘brain gains’ for the migrants’ home countries, and even that it leads to massive welfare gains for the immigrants themselves, but suggest that the non-economic costs of immigration are very large too, and we basically ignore them.

They have in mind costs like increased crime, reductions in social trust, a decline in democratic support for important institutions like the rule of law and free speech, and the dilution of the native culture. To some extent I believe all of these things are costs of certain kinds of immigration, and may justify certain controls on immigration, but none are reasons to support the immigration controls that we currently have.

In this post I’ll consider how much impact immigrants have on the crime rate. I’ll come back to some of the other points in future posts.

So: crime. Crime only seems to rise in line with certain kinds of immigration, and does so for basically economic reasons. A 2013 study looked at two different waves of immigration to the UK – asylum seekers in the 1990s and early 2000s (mostly from places like Afghanistan, Iraq and Somalia); and immigration from the “A8” countries (Poland, Czech Republic and the six other Eastern European states that joined the EU in 2004).

The paper looked at crime rates according to areas where these waves of immigrants settled. It found that neither of these waves had any statistically significant impact on the overall rate of violent crime. A8 immigration actually had a small negative impact on crime rates, driven by a reduction in property crime rates.

On the other hand, asylum seekers did cause a statistically significant rise in property crime, but still a small one. This equivalent to an increase of 0.7% in property crime rates per 1% percentage point share of the local adult that was asylum seekers. Note that this is a percentage increase to the existing crime rate – if crime rates were already 10% and a new wave of asylum seekers suddenly accounted for 1% of the population, crime rates would rise to 10.07%, not 10.7%.

According to the report’s authors,

“Across all England and Wales [asylum seekers] averaged 0.1% of the local adult population, so the average property crime rate might be 0.07% higher as a result – only around 2% of the average property crime rate of around 2.7%. Of course, some authorities had appreciably more asylum seekers located in the area, though shares larger than 1% of the local population were extremely rare.”

What explains this? There might be because of some inherent difference between, say, Polish and Iraqi people, but violent crime levels were not significantly different (in fact, A8 migrants were slightly worse here than asylum seekers). What may explain the difference is that A8 immigrants were free to work however they wished, whereas asylum seekers are not allowed to seek legal employment. The authors of the 2013 report suggest that this explains why only property crime was higher for asylum seekers.

This data is not broken down by nationality, so it is rather blunt. According to another 2013 paper, arrest rates (which are broken down by nationality) were significantly higher for immigrants than non-immigrants – 2.8 arrests per 1000 for UK nationals and 3.5 arrests per 1000 for non-nationals (excluding immigration-related arrests). However, controlling for age this difference disappears. Having more young people seems to lead to more arrests; in and of itself having more immigrants does not.

Finally, there is the issue of second- and third-generation immigrant groups who cause disproportionately more crime. According to the Metropolitan Police, the majority of men held by police for gun crimes (67%), robberies (59%) and street crimes (54%) in London in 2009-10 were black, even though only 10.6% of London’s population is black. There is no easy explanation for this, and it may be due to a combination of factors that we cannot control – or, indeed, easily change.

The ultimate lesson of all this may be that immigration in general does not have a big impact on crime, but certain immigrant groups might if they do not assimilate culturally. Then again, Eastern Europeans don’t seem to be a problem at all, and they seem to be the ones we’re most concerned about right now.

My friend Ed West has a point when he says that there is no such thing as an ‘immigrant’ – only an American, a Pole, a Somali, and so on. In the course of my posts on the non-economic impacts of immigration, I will suggest that a compromise position between my libertarian preference for very free movement and Ed’s conservative preference for restrictions. We may yet be able to square the circle of immigration policy.

QE cannot both boost asset prices and wreck pensions

Quantitative easing is complex and difficult to understand—economists aren't even sure exactly if and how it works. It would be unreasonable to expect non-economists to fully grok its workings even if journalistic explanations were clear and overall true. Since economics journalist's explanations have been largely lacking (including, I expect, my own, when I was an econ journo), it would be very difficult for others, further removed from economics, to 'get it'. Still, this piece on Bank of England staff pensions from Richard Dyson, the Telegraph's personal finance editor, has a number of problems which I can't help but try and correct. Dyson argues that (a) the Bank of England's pension scheme is 'eye-catchingly-generous'; (b) final salary pension schemes have died in the private sector substantially because of the BoE's quantitative easing (QE) programme; (c) QE has harmed pensioners; and (d) the Bank's policy of investing in pension pots in bonds is too low-risk and earns insufficient returns. All are substantially false.

Firstly, the Bank of England's 'generous' pensions are (as Dyson notes at the end) to compensate for lower regular and bonus pay than the jobs that very smart and qualified BoE staff could get elsewhere. Dyson might be right that this, overall, is larger in the public sector, indeed there is a literature suggesting that the total pay + benefits for public sector workers of a given skill and experience level is higher than for private sector workers. But the simple fact of a relatively large fraction of that coming out in pensions doesn't tell us anything on that point—and I would wager that the Bank is run much more like a profit-maximising private organisation than most arms of the state.

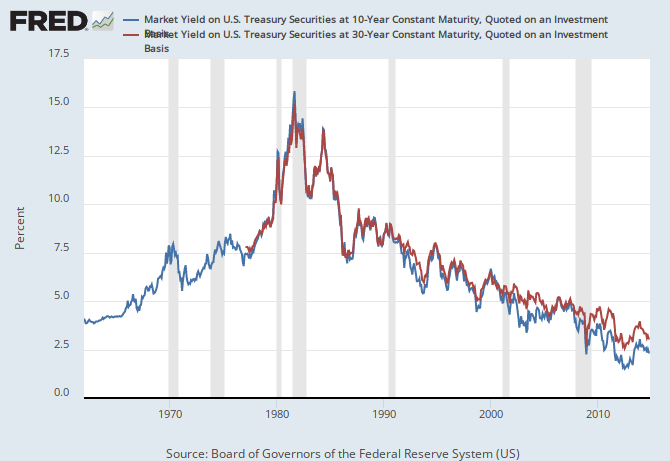

Secondly, as we see in Dyson's graph, private sector final salary/defined benefit pension schemes have been declining since a peak in the mid sixties, with about half of the drop coming in the 70s and about half in the 90s. Practically nothing has happened to them since the introduction of QE.

Which brings us onto thirdly: QE boosts asset prices. QE raises the value of stock markets and bonds and pretty much all securities that people hold in their pensions. QE makes pensioners better off, like it makes pretty much everyone better off. Yes, you've heard that QE leads to lower interest rates. I'm not sure that's true. Remember we are at the bottom of a 30-year slide in real risk-free interest rates, and it seems much less clear that QE is a big factor.

Finally and fourthly, is the Bank too careful with its money? I don't actually have an answer here but I'd suggest that Dyson (and Ros Altmann, who he quotes on this) are a tad too confident. If the Bank invested in riskier equities or emerging markets or whatever, then sure it would be likely to earn a higher return, but would the Bank's critics really give it any slack if these investments went bad, as they'd be more likely to do? I don't really know how the BoE should invest its pension fund, but it seems to me that they are going to be damned if they do and damned if they don't.

So I think we should leave off the Bank and its pension scheme, whatever issues we might have with its macroeconomic management. It pays high pensions to attract talent. It didn't cause the decline in private sector final salary pensions (I think government is probably to blame for that). It's not to blame for high interest rates and it has helped those with pension investments. And we probably don't have the right info to choose its investment portfolio for it.

So marriage is the preserve of the rich these days, is it?

This is something that helps to explain household income inequality in the UK. The idea that marriage is becoming something of a preserve of the rich.

Marriage is rapidly becoming the preserve of the wealthy, twice as common among those safely in the top tax bracket as among the least well-off.Since 2001 those in the top social class, which includes company directors, military officers and university lecturers, have gone from being 24 per cent more likely to be married to 50 per cent more likely, figures from the Office for National Statistics show.

By the time they have children, nine in 10 of the wealthiest Britons are married. However, for those on the minimum wage or less, the figure is about half.

Cue all sorts of worries about the stability of family life and so on. And that's not what we're about here: chacun a son gout is our response to those sorts of concerns. However, this does link very strongly with something else that people claim to worry about a lot, the increasing inequality of household income in the UK.

For we've had something else happening as well. It's not just that the higher income people are more likely to marry: they're also more likely to marry other higher income people than they were in the past. This is of course part of the great economic emancipation of women of the past 50 years. Careers are something for both sexes, not only one. And as it happens people tend to marry those following much the same career path that they are. This is known as assortative mating.

Plug these two things together: professionals marrying professionals, non-professionals increasingly not marrying at all. We're going to end up with a lot of two high income households and a lot of low one income households. Thus, inevitably, household income inequality is going to increase.

And, short of telling people who they may marry or not, there's not a great deal that can be done about this.

The lesson of not being able to find sandwich makers in Northampton

It would, of course, have to be The Guardian that manages to get the story of looking for sandwich makers in Hungary completely arse over tip. We mean, of course, come on, it would just have to be, wouldn't it? The story being that a company that makes pre-packaged sandwiches for the supermarkets and the like finds that its new factory in Northampton is finding it difficult to recruit workers. So, they go off to an agency in Hungary to see if anyone there would like to relocate. That's the story we're being told, don't worry over much about the details. At which point Mary Dejevsky (for it is she) tells us that:

The UK, I fear, persists in the delusion that it is a high-skilled high-productivity, high-pay economy when for at least a decade or more it has been nothing of the kind.

What?

If this were a low-skill, low-pay economy then there would be armies of people willing to do low-skill, low-wage, jobs like making sandwiches. That there are Hungarians willing to relocate shows that Hungary quite probably is such a low-skill, low-wage, economy. Further, that the UK apparently needs to import such low-skill and low-wage labour shows that the UK economy is offering higher-skill and higher-wage jobs to the indigenes.

The very story being used to prove the contention in fact proves exactly the opposite of the contention being made. People have better options than low-skill, low-paid jobs. Thus the UK economy cannot be said to be reliant upon low-skill, low-pay jobs.

What is so difficult about this for people to understand?

There's less to this robots will steal all our jobs story than you might think

We've another of those spine chilling warnings that the robots are going to come and steal all our jobs:

From self-driving cars to carebots for elderly people, rapid advances in technology have long represented a potential threat to many jobs normally performed by people.But experts now believe that almost 50 per cent of occupations existing today will be completely redundant by 2025 as artificial intelligence continues to transform businesses.

A revolutionary shift in the way workplaces operate is expected to take place over the next 10 to 15 years, which could put some people's livelihoods at risk.

Customer work, process work and vast swatches of middle management will simply 'disappear', according to a new report by consulting firm CBRE and China-based Genesis.

We could all get very worried and ponder what it is that people might do. Alternatively we could be sensible and give the correct answer: something else. And even if that something else is something that isn't currently thought of as a "job" that doesn't matter one whit.

For we don't actually care whether someone, anyone, has a job. We don't, really, care whether they have an income either. What we do care about is that everyone has the opportunity to consume. And if the robots are off making everything then obviously there's lots to consume. So we've not got a basic nor an insurmountable problem here. All that's necessary is some system of getting what is produced into the hands of someone who can consume it.

And oddly enough we've got that system, that market for labour. We've had it for many centuries. The idea that someone might make a living as a writer of books (as opposed to a court funded artiste) would have been ridiculously exotic a few centuries back. The idea that a sprinter might make a living from sprinting was near illegal only 50 years ago. The idea that someone can make a living as a free market diversity adviser (they're not all tax funded) still seems pretty exotic to us frankly.

As has happened before, as has been happening for centuries, as the machines take over the much spreading then the muck spreaders go off to do something else. Usually, something a little less smelly and more enjoyable for a human being to do.

And there's one more observation we should make here. 50% of the jobs are going to disappear in 15 years? Pah! Lightweights.

For people always forget about "jobs churn". The economy destroys some 10% (for the UK, 3 million) jobs each year. Unemployment doesn't rocker by that amount because the economy also, roughly you understand, creates 3 million jobs each year. Those that disappear might appear to be the same as those that are created but they're almost always not quite. The move from one job to another always involves a subtle shift in what is being done. And continual subtle shifts in the flow of jobs move the stock of jobs along at a fair old clip.

We already expect some 150% of jobs extant in this current economy to explode, disappear, and be recreated as slightly different ones over the next 15 years. Whether this 50% is included in that figure or on top of it it's not the revolution some are predicting: it's just an addition to hte normal workings of the economy.