Economic Nonsense: 11. Inflation is a price worth paying to boost employment

It used to be thought there was a trade-off between inflation and employment. The economist William Phillips published a 1958 paper in which he found an inverse relationship between money wage changes and unemployment over nearly a century. The relationship was called the Phillips Curve, and was used by legislators to stimulate the economy by inflation to boost employment rates. Unfortunately the Phillips Curve went vertical in the 1970s as countries were beset by high inflation and high unemployment occurring simultaneously. People were building expectation of inflation into their calculations and their economic decisions. Inflation rewards debtors at the expense of creditors and makes people less ready to lend. Investment in productive activity diminishes.

No less seriously, the assumption of future inflation makes forward planning difficult. People do not know what money will be worth by the time their goods reach the market. What inflation does do is cause misallocation of resources. People see the new money created by government and make false assumptions about what they should invest in. When they find that the demand was unreal, goods go unsold and there is an economic downturn with increased unemployment. This brings about the 'stagflation,' in which high inflation and high unemployment happen together.

Inflation can reduce unemployment in the very short term, but only at the expense of more unemployment following afterwards. This is why some governments have boosted inflation in an election year to take advantage of the apparent stimulus, then face the recessionary consequences after the election is safely out of the way. The strategy is now called boom and bust because an inflationary boom is followed by a real-world bust.

Democracy is the concept that the people should get what they want

Good and hard, as Mencken put it. But even so some of the things that people want surprise. As in this Owen Jones piece:

According to the opinion polls, most Britons want public ownership of rail and energy, higher taxes on the rich and a statutory living wage.

A statutory living wage?

The poll of 1004 employed people shows that 71% of Labour voters, 66% of Lib Dems and even 44% of Tories (60% overall) say we should increase the Minimum Wage to a Living Wage – and that the government should make the Living Wage the legal minimum. There is majority support for such a move across all regions of the country and all social class groups. Interestingly, the group who most agree that a Living Wage is needed (even if it costs jobs) are the D/E social class group – working class voters who are more likely to be paid the minimum wage, and know how hard it is to live on the poverty line.

The argument against the Living Wage becoming the legal floor is that it would cost jobs – which is exactly what was said about the Minimum Wage, and it didn’t happen then. However even if that is the case, the public still think poverty wages are something that should be a thing of the past.

The problem with this is that the pe4ople don't know the truth about that living wage. That it is a pre-tax number. They also don't know that if we did not charge income tax and national insurance to those low wages (as we have repeatedly argued that we should not) then the current minimum wage would provide a higher post-tax income than the proposed living wage would with the current tax system. They don't know this because the current agitators for the living wage don't tell them.

And the reaction really will be different if the question is properly couched. For example, would you support the ending of tax poverty? would be an interesting formulation.

For that's actually what we've got, not low wage poverty but tax poverty.

Economic Nonsense: 10. Government spends more efficiently than private individuals

This is not only untrue; it is laughably untrue. Sometimes supporters of big government spending claim that government is more efficient because it doesn't need to make profits. Sometimes they say it doesn't need to spend on advertising. Sometimes they say it can borrow more cheaply than private businesses because it has taxpayer backing. The facts show that even with profits, advertising and higher borrowing costs, the private sector is vastly more efficient. The UK's nationalized industries were ailing giants that gobbled subsidies when they were state-owned. When they were privatized they became profitable private companies that paid taxes instead of collecting subsidies. Private investors are more careful because it is their own money at risk. The public sector corresponds to the fourth quarter of Milton Friedman's quadrant: they spend other people's money on somebody else. The private sector is competitive; it has to attract funds competitively. It has to anticipate future demand to avoid investing unproductively. Private projects seek ways to curb costs, to employ people efficiently, and to keep as close as they can to a timetable.

Public projects are notorious for cost overruns, for over-manning, and for being completed years behind schedule. Private projects are undertaken in response to market signals; they are subject to commercial pressures. The aim is to produce items that will meet future demand and generate profits. Public projects, by contrast, are subject to political pressures. They are often undertaken with a view to electoral popularity. The projects chosen, their scope and their location are often undertaken to secure the backing of various interest groups and localities, in the hope that this will translate into electoral support. None of this makes for efficient spending by governments.

Remarkable what you can learn from bishops these days

The Anglican bishops have decided to tell us all something about how to achieve the good life. Amazing what you can learn from bishops these days really:

Adam Smith, the father of market economics, understood that, without a degree of shared morality which it neither creates nor sustains, the market is not protected against its in-built tendency to generate cartels and monopolies which undermine the principles of the market itself.

No, not really. Smith thought the market would do just fine. But that there will always be attempts to use the law and regulation in order to privilege certain producers into those cartels and monopolies. It was actually Karl Marx who insisted that markets inevitably led to monopolies, Smith who pointed out that not messing with markets with regulation was an aid to preventing monopolies.

But we are also a society of strangers in a more worrying sense. Consumption, rather than production, has come to define us, and individualism has tended to estrange people from one another. So has an excessive emphasis on competition regarded as a sort of social Darwinism. (This is a perverse consequence of allowing market rhetoric to creep into social policy. For an economist, competition is not the opposite of cooperation but of monopoly).

Yet that is extremely perceptive. We might go further (as we do) and argue that competition is actually how you decide to cooperate with, the first being the precursor to the second. The supplier to the steel mill is, after all, cooperating with the steel mill in being a supplier.

One important principle here is the idea of subsidiarity – the principle that decisions should be devolved to the lowest level consistent with effectiveness. Subsidiarity derives from Catholic social teaching, and it is a good principle for challenging the accumulation of power in fewer and fewer hands. It does not mean that everything must be devolved to the most local level. Nor is it about handing small matters downward whilst retaining all meaningful authority in the hands of the powerful.

We would most certainly support that. We might insist that rather more things can and should be done at rather lower levels than some others but we're absolutely fine with the general principle.

As an example, “post code lottery” has become a term of disparagement for local variations in public services. But that implies that a single standard, determined and enforced nationally, is the only way to order every aspect of public life. It is certainly true that many services should be available as equally as possible to every citizen. But it is also true that different communities have different needs and may choose different priorities. If people feel part of the decision-making processes that affect their lives, there is no reason why, in many aspects of social policy, local diversity should not flourish.

Quite, who wants a monolithic drabness to the nation?

The desire for neatness, as much as the desire for control, is characteristic of how politicians tend to think – especially those in government or contemplating office. They are often backed up by bureaucracies which are allergic to messiness. But human life and creativity are inherently messy and rebel against the uniformity that accompanies systemic constraints and universal solutions.

By now we're rather wondering whether there hasn't been a revolution in the Anglican Church. Perhaps an influx of Austrians?

Whether on the political right or the political left, it is a long time since there has been a coherent policy programme which made a virtue of dispersing power and control as widely across the population as possible.

We have been chanting that lonely hymn for some time now.....

This document is much more interesting than the predictable ways that the various newspapers have been covering it. interesting in the sense of being something of a curate's egg: parts of it are excellent.

Economic Nonsense: 9. International agreement on tax rates would benefit everyone

International agreement on tax rates would hurt everyone except those who collect and spend taxes. Governments have little restraint on the degree to which they can take the money earned by their citizens and spend it on overblown projects designed ultimately to buy votes and secure their re-election. They meet some resistance as they increase their tax take, but people can do little except grumble. Very often there is little difference between the major political parties, or between the tax rates they levy while in office, so democratic restraints are minimal. The one effective restraint is the ability of people to move to another jurisdiction. This is especially true of modern economies which place considerable value on the talents of high-achieving individuals. Government is restrained on what it can tax them by their ability to move. When faced with punitive tax rates, they can relocate to somewhere more favourable. High earners in France, and those with aspirations to become so, began to leave the country in significant numbers when faced by government plans to levy a top income tax rate of 75%. Similar effects have been observed elsewhere.

What is true of individuals can be true of companies. They, too, can choose to relocate to areas where tax rates are friendlier. The Republic of Ireland found its low 12.5% rate of corporation tax attracted companies to base themselves within its borders. High rates of corporation tax elsewhere added to Ireland's attraction.

Those who support high taxes dislike this restraint and many of them call for international harmonization of tax rates. The aim of this is to make it pointless to relocate, and to remove the one curb on over-large and over-costly governments. They dislike what they call 'tax competition.' But relatively low taxes on high earners and business constitute a business-friendly environment and are conducive to economic growth. Those who call for harmonization are in effect saying they do not want any countries to be more business-friendly than others. Denied an escape to less oppressive tax regimes, people become the helpless prisoners of rapacious governments.

If only the people who rule us actually knew anything

Hayek pointed out that it's impossible for the centre to have enough information to be able to plan the economy. In one sense therefore, to find that our rulers are ill informed is consoling: Hayek was in fact right. In another it's not so good, for they will insist on gabbling on about things they really don't understand. Today's example is Tim Yeo:

Yeo believes fossil fuel companies must prepare themselves for a different kind of low carbon world.

“There may well be national [carbon] performance standards. There may well be caps everywhere. We now have a nuclear non-proliferation treaty, we may have then a coa-fired power station non-proliferation treaty and you can monitor these things externally.

“Or we may have a carbon price at $50 and investors think ahead so they think the world will have to be a low carbon one in the 2030s and pension funds with 25 year time horizons must take this into account. So the oil companies and the gas companies have to recognise this.”

OK. And here is the head of Shell indicating that they know this.

There’s much to do if we are to build a lower-carbon, higher-energy future. For Shell’s part, we wholeheartedly support the World Bank’s recent call for a carbon price to be applied throughout the global economy. Carbon pricing is one vital step, but there’s a long road ahead. To build the energy future we need, government, business and civil society must work together. With the right approach, one characterized by pragmatism, it can be within our reach. And, as CEO, I am determined that through our production of natural gas and our efforts to advance CCS, for example, Shell will continue to play our part.

Further, Shell has made it very clear that they already apply a carbon price in their evaluations of future investments (the only place that it's of any importance, sa projects currently producing are of course sunk costs).

So that Yeo ill informed in the specifics. But he's also ill informed in theory as well. He's getting very het up about the idea of "stranded reserves". This is the idea that the reserves that the oil companies are thinking about pumping up in 30 years' time never will be pumped up because of those climate change worries. Therefore those oil companies must recognise that risk on their balance sheets today. Write down the future value of those reserves perhaps. Which is simply an idiot thing to say.

Because we've had that whole dang report from Lord Stern discussing exactly this point. In which he goes on for several chapters pointing out that we shouldn't use market interest rates to measure the costs of something far in the future. OK, so, great, we don't when we talk about the costs of climate change. For if we did then those future costs would be, in he money of today, so small that we'd never do anything about it all. OK, make up your own minds on what you want to think about that.

But look at what that means about the values of those future reserves. We are discounting them to their present value at market interest rates. Because, obviously, we're valuing Shell's shares not at the value of those reserves in 30 years time but at the net present value discounted by market interest rates. Thus the value of those future reserves as contained in today's Shell price is piffle. Near nothing, because as Stern pointed out, discounting at 30 years and more at market rates makes something worth near nothing.

Thank goodness we don't have a planned economy, eh, given then knowledge held by those who would be doing the planning.

Economic Nonsense: 8. The world is running out of scarce resources

Curiously, the opposite is true: so-called 'scarce' resources are actually becoming more plentiful. Our technical ability to extract resources, including things like copper, zinc, chromium and manganese, is increasing faster than the rate at which we are using up existing 'reserves.' We use the term 'reserves' to denote the supply which can be extracted economically with current technology. For most of these resources our reserves are increasing. We can measure the relative availability of these resources by looking at their price. For many of them it has been going down over several decades, indicating a relative excess of the supply of them over the demand for them. Julian Simon won a famous public wager with Paul Erlich, predicting lower prices for an agreed basket of resources, and Erlich duly paid up when he lost.

If any resource does become genuinely scarce, the price rises, and this signals to people that they should use less of it, turning to substitutes where they have become more economic to develop. It also tells people to produce more of the scarce resource, with the higher price making previously marginal sources now more economic to develop. The price mechanism thus acts to counter their scarcity by reducing demand and augmenting supply.

Oil and gas were long thought to be exceptions to this trend, but even here technology has given us access to new supplies. Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has made available sources of oil and gas from places less volatile politically than those we previously depended upon. Prices have tumbled, and cheap shale gas is enabling us to shut down coal-fired power stations and switch to much cleaner gas-powered ones. Some estimates put the supply of shale gas as sufficient to supply projected needs for the next 200 years. Long before then, however, photovoltaic technology will have allowed solar power to overtake gas in its cheapness. Contrary to what doomsayers claim, we are running out of neither resources nor energy.

Economic Nonsense: 7. New technology destroys jobs

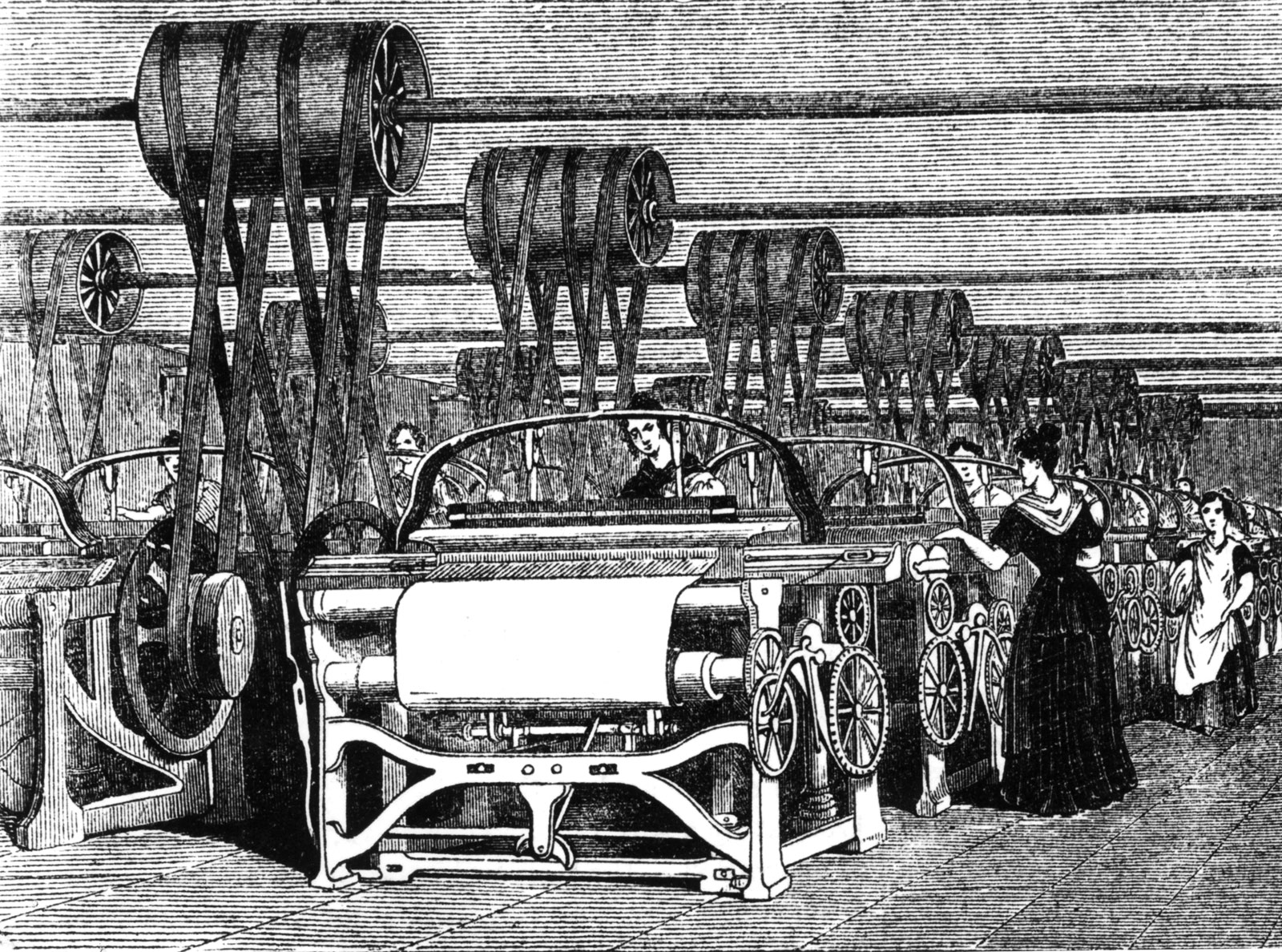

This is partly true, but in a misleading way. New technology has often displaced people from their traditional occupations, but in doing so it has created the wealth that has enabled vastly more jobs to be created than were lost. Agricultural technology meant far fewer jobs for farm workers, but it also meant cheaper, more abundant food that left people able to afford things sustained by newer jobs. A similar effect occurred with early textile technology. Spinners and weavers were displaced, but cheaper, mass-produced textiles enabled people to afford other things that led to other jobs. This is how economic progress is made. People develop new products and new processes that people prefer over what they were doing before. Jobs are lost and more are created as part of that churn.

Voices are often raised against the change, especially by those affected, with calls for restrictions to be imposed on new technology in the name of protecting jobs. Sometimes it has led to violence. The Luddites smashed machinery, while the Saboteurs were named from throwing their wooden shoes (sabots) into the machines to wreck them. This was done in a vain attempt to halt the march of progress.

New technology can bring hardship upon those affected by it, and some of those displaced can find it hard to secure alternative employment. Governments, rather than attempting to stop new technology, sometimes try to ameliorate some of its effects by funding schemes that help retrain and if necessary relocate those most affected by it.

Sometimes people will ask where the new jobs will come from if technology displaces traditional ones. The question cannot be answered because the future is inherently unpredictable. New technology makes things cheaper, and that leaves people richer, with more money to spend on other things. We don't know what those other things will be, but we do know that they will involve new types of jobs. New technology, in making manufactured good cheaper, has left people with more to spend on services industries, and there are more jobs in total than there were. This is how new technology works. It destroys some jobs and creates more.

Economic Nonsense: 6. The rich are growing richer, the poor poorer and the gap is widening

Sometimes this is asserted on a world scale, and sometimes claimed to be true within individual countries. Not only is this nonsense; it is also false. The rich have indeed grown richer, and the poor have also grown richer. It matters more to poor people. Extra wealth to the rich might mean more luxuries; to the poor it can mean the difference between starvation and survival. The last few decades have witnessed the greatest advance in living standards for the world's poor than ever before in human history. More than a billion people have been lifted above subsistence. The poor have not become poorer, they have become richer to a spectacular degree. India and Chine have made astonishing advances, but it has not been confined to them; other countries have seen their poor become wealthier, and it is still happening.

Within rich countries the poor have become richer. The yardstick that matters is the one that tells us how much they can buy. In terms of the hours of work needed to buy goods, they are much better off than they were decades ago. In some cases what used to take weeks of work to buy now takes less than a day.

Those who make this false claim are concerned with equality rather than wealth. If the poor gain wealth, but the rich gain more, then under their perverse way of regarding things, they regard the poor as having become poorer. If achieving twice the spending power is called "becoming poorer," then words have lost their meaning.

On a world scale decades ago there were a handful of rich countries with the rest dirt poor. Since then many poorer countries have climbed the ladder to wealth, and others are doing so. Globalization and the spread of market economics have brought an explosion of wealth that has been widespread and beneficial, and promises to continue being so.

On our little list of things not to worry about

OK, so this is only a letter to The Guardian but it still betrays a certain mindset that we find ourselves being very confused by:

He talks about the future of businesses based on a new Companies Act, but it’s not clear how this would address the problems presented by 40% of shares in major UK companies (including utilities) being foreign owned.

We're confused because we simply cannot see why this might be a problem. The foreign capitalists are sending their lovely foreign capital into our country. This means that there is, other things being equal, more capital in this country than there would be without that lovely foreign capital. Given that it is capital added to labour that increases the productivity of labour, the average productivity of labour is what will determine the average income in the country, this means that foreigners sending their lovely capital to our rainy little island means that wages are higher here in the rain than they otherwise would be.

And we think this is a good idea.

As to why there is this concern our best bet is that old problem of the British left. All too many socialists are also quite ghastly nationalists. A combination we had rather too much of in Europe in the last century so hopefully not something that's going to become popular again.