Beat combos are not quite our thing, however

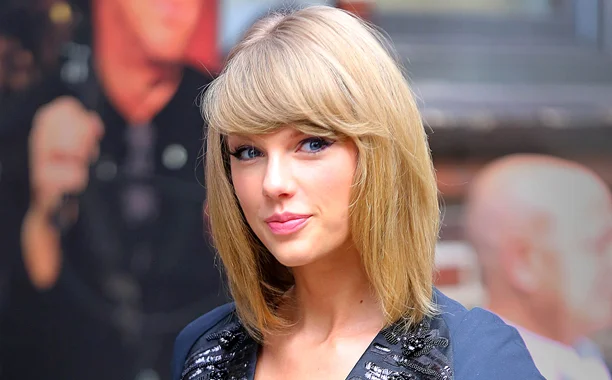

There is something of interest to be gleaned from this little story about Taylor Swift and her interaction with Apple's new music streaming service:

Apple has apparently changed its policy and pledged to pay musicians for the use of their work during a free trial of the Apple Music service following an open letter from US pop star Taylor Swift.

We'll admit that which young lady warbles away at the front of the latest popular beat combo is not normally our thing. [Speak for yourself! – Sam] But it's worth noting who has the economic power here. On the one hand, the most valuable publicly listed corporation on the planet, one that makes a Bill Gates sized fortune in profits each and every year, with cash reserves measured in the hundreds of billions. On the other one young lady in her 20s.

Yet when the two clash over the division of revenues it is that young lady who wins. The interesting economic lesson being that it is not size, or the corporations, or wealth, that wins. It is who controls the scarce resource that does.

Swift's music is (oddly to us but there we go) extremely popular. It is a must have for any music streaming service. Thus she being the one hold out will make that giant corporation change the terms it offers to everyone.

It is not size, or who has the most lawyers, or the most money, which wins in a market economy. It is scarcity that rules. Which is, of course, just how we like it, for our task in an economy is to decide how scarce resources are allocated.

Will HM Treasury learn lessons from HSBC?

HSBC executives have done stupid and illegal things for which they should be penalised but mostly the bank itself has carried the can: that’s you and me and the other customers, shareholders and employees. The reality is that HSBC is far weaker than it was 10 years ago due to management folly but fines and punitive taxation makes the corporate entity weaker still. We are the losers from that cycle, not the miscreants.

The big banks have wrongly been blamed for the 2008 financial crash. Governments, notably the US government, and poor performance by the regulators were far more responsible. UK financial services were indeed silly to get involved in the game of “pass the parcel” with the massive dodgy debts but that problem was secondary. UK management was hooked by the algebra which they pretended to understand when more sensible bankers, like the Rothschilds and the Canadians, did not join in.

Mark Carney assured the City this month that the bad old days are over and banks are cleaning up their act. Management is better than it was but it has a long way to go. Unfortunately they are impeded by government in the two ways that HSBC cites as reasons to leave London: excess taxes and regulation. Banks no longer make huge profits and even if they were, that is no reason to tax them more than any other profitable company. A better solution is greater competition. New banks are trying to break in but the regulators, contrary to what they say, make than difficult.

The Chancellor may lighten the banks’ tax load next month but, in any case, excess regulation is the bigger problem. One of the new homes HSBC is contemplating is Luxembourg. That is interesting: they would then have to meet all the EU financial regulations but not the extra burden dreamt up by London’s regulators.

It is baffling that the Chancellor, in calling for a single EU market for financial services with less regulation, does the very opposite himself. A single market needs a single set of regulations and yet the British insist on having our own which can only be additional to the EU rules. This form of jingoism is suicidal: ultimately it will lead to the demise of the City of London as Europe’s financial capital.

Compliance with these London regulations loads costs on financial services and their customers at least twice over. The costs of the regulatory agencies have to be more than matched by the compliance teams in the sector. The competitiveness undermined in the City will be taken up elsewhere in the EU and the global markets. HSBC are not the only company considering departing these shores. When they are gone, it will be next to impossible to get them back.

But is anyone in HM Treasury listening?

The Bank of England’s non-convincing non-response to yesterday’s ASI report on its stress tests

The Bank of England declined to comment on the ASI report “No Stress: The flaws in the Bank of England’s stress testing programme,” released yesterday. They did however point to evidence given by Bank of England official Alex Brazier to the Treasury Committee, in which he described the stress tests as “really tough”.

Oh yeah?

Well, the stress assumes that GDP growth falls to -3.2 percent before bouncing back, inflation rises to peak at a little over 6.5 percent, long-term gilts peak just below 6 percent and unemployment peaks at 12 percent.

This is not a particularly severe stress when judged historically or by contemporary experience in the parts of the Eurozone, where we have much larger falls in economic activity and much higher unemployment rates.

The impact on this supposedly severe test on the banking system is also very mild. The unweighted average of capital to risk-weighted assets falls from 10 percent to a low of 7.3 percent before bouncing back a bit, and there is a similarly mild dip in aggregate profits. One gets no sense of large losses on banks’ bond or interest-sensitive collateral and loan positions, and the Bank’s scenario is notable for the absence of any major institutional failure: the scenario omits the severe knock-on effects one would expect from a severe downturn.

This suggests to me that the modelling of the banks’ response to the external shocks assumed in the stress is, well, not particularly stressful.

One would like to stress that the whole point of a stress test is to actually stress.

Kevin Dowd is the author of our new publication 'No Stress', which you can read here

Compass come up with the most wonderful ideas

Compass is that little gabfest that wants to pull Labour in a more lefty direction. Which is lovely of course, the more Corbyn-like it becomes the less anyone else ever has to worry about it winning an election ever again. But it also does have to be said that the folks at Compass aren't really all that au fait with reality. Which is rather part of their charm in fact:

Sales offer a one-off windfall – the family silver can only be sold once. They mean the permanent loss of collectively owned public assets, and the income that they deliver over time, both built up over many decades. Although such sales can reduce the cash debt at a given moment, they aggravate the problem of public indebtedness as the asset base which helps to balance the debt shrinks away. This is simple short-termism that will be paid for by subsequent generations.Yet there is an alternative approach that would limit the long term impact of persistent privatisation. The sell-off of what remains of the family silver is set to continue, but at least the proceeds should not be passed lock, stock and barrel to the Treasury.

Instead of disappearing into the Treasury black hole, the proceeds from privatisation could instead be paid into a newly created Public Investment Fund, a collectively owned, social wealth fund. In this way, the benefits of historically accumulated public assets could be used to fund a range of public projects that benefit society as a whole, including investment in economic and social infrastructure. There would also be much greater transparency in the way the revenue is used.

Strangely, we find that we agree with them. Yes, instead of privatisation receipts being frittered away on whatever the government of the day think will buy it votes, why not have a fund that's all about investment? Which is where reality raises its ugly head. We've already got one of those, it's called the national debt. For that national debt is the accumulated balance of public "investment" in all these lovely things that are being sold off. And we're OK with the idea that the lovely profits that we're all making from selling off those public assets be reinvested in creating the next generation of them that can be sold off in the future.

But do note what profit means: it means that there will be an excess left in that national debt, that there will be a national surplus, after we've done our privatising. For it's only if that is true that we can say that those past public investments have been profitable. So, when Compass manage to identify those assets that can be sold off to pay off the entirety of that national debt, that national debt which is the result of all of those past public investments, we'll be right there with them calling for not only the sales but also of the proceeds of those sales to that special fund. And then, once they've shown that public investment is indeed profitable then we'll let them do some more, shall we?

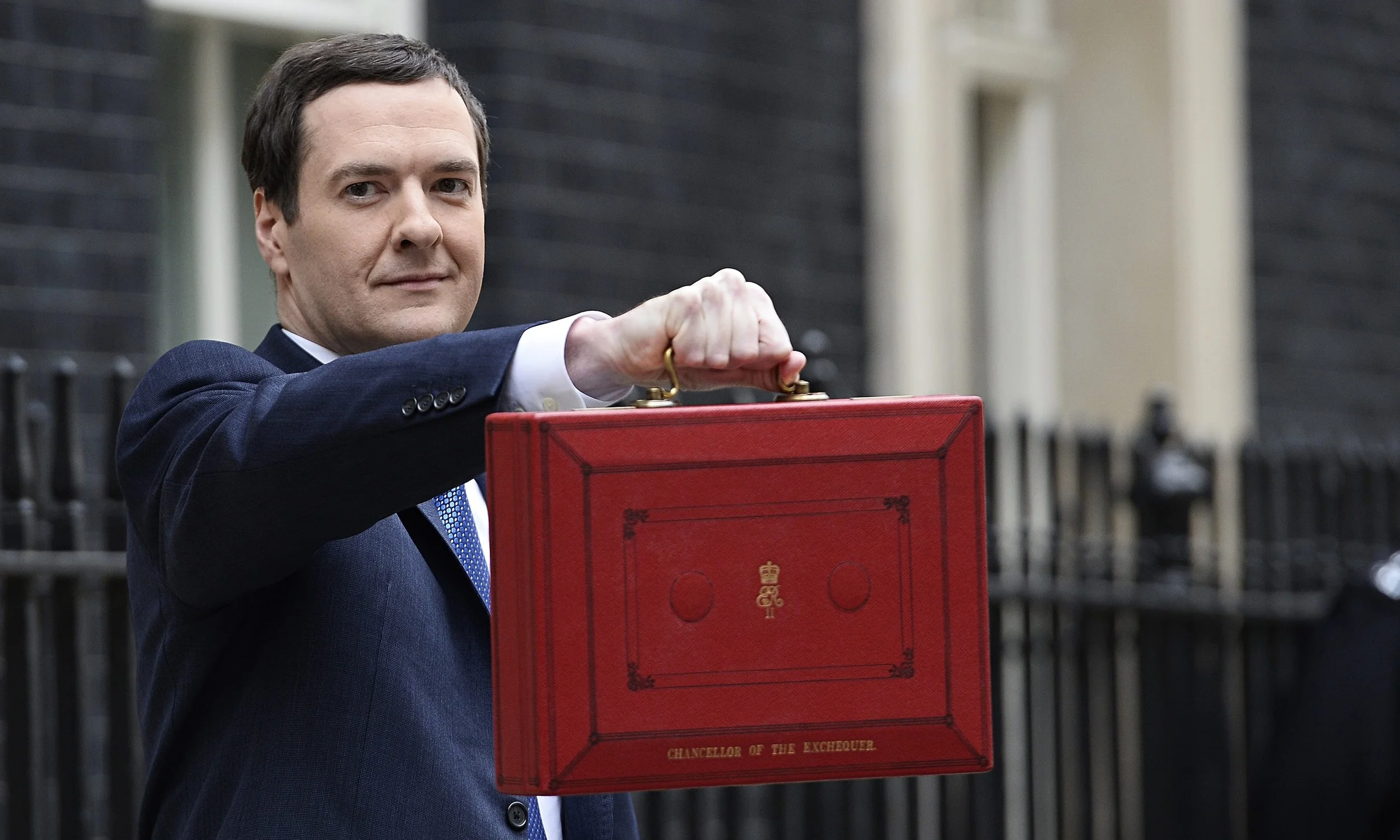

The Chancellor should unleash his inner self

As Chancellor of the Exchequer Nigel Lawson made it a feature that in every one of his budgets he would simplify taxes and abolish at least one tax altogether. George Osborne has been dealt a difficult hand, but has played it reasonably well, achieving the highest growth rate in Western Europe, and helping the UK economy create more jobs than the rest of the EU combined, more than 1,000 each day.

One senses that he is at heart a believer in simplifying taxes and lowering them wherever possible. He wants to emulate Nigel Lawson, perhaps, but is constrained by the need to bring down the deficit and the debt. Nevertheless, he could take his first steps down Lawson Street in his July budget.

First the abolition. He should end stamp duty on shares. This tax diminishes the capital available to companies for investment and expansion. It takes money from pension funds and decreases both the size of people's pensions and the incentives to save for them. Its abolition would immediately increase the value of listed companies, augmenting their capital, and, as Tim Worstall points out, extra capital allied to labour increases productivity and the potential for wage increases. Abolition would thus be a gain for both pensioners and workers, and the growth generated would soon repay its Treasury shortfall.

For simplification, National Insurance must be a prime candidate. It is a tax in all but name, and a complex one at that with its various classes and sub-classes. It is calculated differently from income tax and with different thresholds. It is a huge burden on employees, especially on the low-paid. Even the so-called "employer" contribution in fact comes from the wage pool that would otherwise have gone direct to the employee. Many business leaders and economists have called for NI to be merged with income tax. The Chancellor could make a start in his July budget by having NI calculated in the same way as income tax, and subject to the same thresholds. This would avoid many of the costs that the present duplication entails, as well as making life simpler for employers calculating deductions for their workers. It would also make it more transparent.

The call, therefore, is for lower taxes and simpler taxes. Over to you, Chancellor.

There's some serious idiots out there

So, another one of these attempts to make clothes only from local ingredients. Rather ignoring much of the human history of trade which has seen extensive trade in textiles and clothing pretty much ever since human beings started wearing them. But sure, why not experiment?

In December, just under 2,000 limited-edition oatmeal-colored cotton hoodies cropped up at The North Face’s online and brick-and-mortar stores, commanding a premium price of $125 each. By January, the hoodies were sold out.These shirts spun an interesting tale. They were an experiment by the sports clothing company to see if everything it needed to produce the hoodie — from the cotton to the finished garment — could be found within 150 miles of its headquarters in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Well, they couldn't do it but so what. A market economy is that continual succession of experiments, we cast off the ones that fail. However, here's where the ignorance of what is staring one in the face comes in:

The North Face hoodie was part of its Backyard Project, which is part of the company’s effort to work closely with the US textile industry, from farmers to factories, to use sustainably grown materials and reduce waste.

Reduce waste is a synonym for using fewer resources to create a particular output. And we've already got a system to do this: it's called that market and those prices. At which point it's terribly simple to work out whether such localism reduces resource consumption.

These "local" hoodies cost that $125. The standard, non-local hoodies by the same company cost $45 to $55. Making the entirely reasonable assumption that they're applying the same standard mark up to both products this means that the local version consumes more than twice as many resources as the non-local one.

We can work out resource use just by looking at prices.

Intellectual property: in search of real evidence

There are many problems with economic research on the costs and benefits of intellectual property protections. For one, the most common measure of research output is the rate of patenting; but changing the strength of patents both changes the incentives over doing research and the incentives over patenting that research, introducing a huge bias.

For another, a lot of what you want to measure is pure counterfactual: what would have happened under a different (i.e. stronger or weaker) intellectual property system—but how can we track research that might have happened but didn't actually? There is little info kept on, for example, promising drug compounds that pharmaceutical firms never followed up on.

A third is that patent laws are fairly uniform within countries. Where they vary in practice across areas the industries are often too variegated to accurately compare. There are some variations across the developed world, but aside from the fact that countries systematically vary in relevant ways, small changes in individual countries' policies are rarely big enough to matter. If Denmark changes its standard term length from 17 to 20 years this has very little impact on the incentives international firms face.

Canny researchers have tried to get around some of these problems. For example Lerner (2009) looks at the impact tighter patent protection in Austria has on patenting by Austrians who live in the UK. Though stricter patent provisions did lead to more patenting within a country, it was not associated with extra patenting by nationals abroad.

Other research has attempted to measure total Research & Development spending, total scientific papers published, total citations to scientific papers, or even clinical trials and drug approvals, in order to get a better grip on the actual pace of innovation.

A highly interesting new NBER paper by Heidi L. Williams at MIT, entitled "Intellectual Property Rights and Innovation: Evidence from Healthcare Markets" (pdf) lucidly explains these problems and the standard framework for economic research on intellectual property. Viz: does the free market under-provide research without IP? Do the benefits IP rights generate in terms of extra innovation outweigh the costs of restricting an idea's use for 20 years or more?

Williams manages to identify a variation between the delay in commercialising early-stage and late-stage cancer treatments, and hence the effective length of the patent (even though the statutory length is the same). Firms patent when they discover things, not when they commercialise them, and this means that the length of Federal Drug Agency trials and other hold-ups influence how long they actually get a monopoly on a drug's sale. In this context, late-stage cancer drugs are often rushed to market, whereas early-stage cancer drugs take longer to approve (and hence firms get a shorter effective patent).

Williams finds that shorter commercialisation lags lead to more investment in innovation in that area.

Taking advantage of our surrogate endpoint variation, we estimate counterfactual R&D allocations and induced improvements in cancer survival rates that would have been observed if commercialization lags were reduced. Our back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that the distortion of private research dollars away from long-term projects has quantitatively important implications for the survival outcomes of US cancer patients: we estimate that among one cohort of patients - US cancer patients diagnosed in 2003 - longer commercialization lags generated around 890,000 lost life-years. Valued at $100,000 per life-year lost (Cutler, 2004), the estimated value of these lost life-years is on the order of $89 billion for this single cohort of patients.

Pretty strong results for IP advocates, but more importantly a very promising avenue for further research.

The problem with identities in economics

Obviously, George Osborne's plan to make budget deficits illegal is just a piece of politicking. For it's only "illegal in certain circumstances" and being in a recession is a special circumstance. So, actually, it's really just a restatement of the Keynesian orthodoxy, that there should (can be if you prefer) be fiscal stimulus in a recession and there should also be fiscal austerity in the boom so as to reduce the white hot heat of that technological revolution. Shrug. But it's got all the right people het up as this letter to The Guardian tells us:

Economies rely on the principle of sectoral balancing, which states that sectors of the economy borrow and lend from and to each other, and their surpluses and debts must arithmetically balance out in monetary terms, because every credit has a corresponding debit. In other words, if one sector of the economy lends to another, it must be in debt by the same amount as the borrower is in credit. The economy is always in balance as a result, if just not at the right place. The government’s budget position is not independent of the rest of the economy, and if it chooses to try to inflexibly run surpluses, and therefore no longer borrow, the knock-on effect to the rest of the economy will be significant. Households, consumers and businesses may have to borrow more overall, and the risk of a personal debt crisis to rival 2008 could be very real indeed.

This is true, in one model, because that's how we set that one model up. Indeed, it's how we define that model. But we must not confuse the model with the economy, nor the map with the territory. For there's no particular reason why there has to be inter-sectoral lending or borrowing at all. There can, obviously, be intra-sectoral such. Some companies are cash rich at present. Some households are at that stage of life where they have significant savings and or assets. Some companies desire borrowing, as do some households. There's no reason at all why there must be lending or borrowing across those sectoral boundaries, nor why government should be taking any part in any that does happen. It's simply a construct of our model that we think it must. And, again, models are not reality.

Our economists are getting rather carried away by the constraints of the models they're using. But then, a group letter to The Guardian signed by Andrew Simms, Richard Murphy and Howard Reed. We knew it was going to be wrong, didn't we?

The public wealth of nations

In 2013's Cash in the Attic ASI fellow Nigel Hawkins detailed £600bn of assets the government owned, but had never subjected to a market test. The paper recommended selling 10% of the assets off to begin with, in order to subject them to the market test and see if they were being best used, as well as giving the government money to reduce the national debt A new book, The Public Wealth of Nations, written by Dag Detter and Stefan Fölster, argues a lot of the same points—although with a much broader scope and deeper focus. The book's blurb runs:

When you look around the world it's almost as if Thatcher/Reagan economic revolution never happened. The largest pool of wealth in the world – a global total that is twice the world's total pension savings, and ten times the total of all the sovereign wealth funds on the planet – is still comprised of commercial assets that are held in public ownership.

And yet, while this is the largest pool of assets in the world, is also one of the murkiest – what goes on inside them is often not even properly known by the governments who own them. In most countries this vast portfolio is both a fiscal and political burden on society. If professionally managed it could generate an annual yield of 2.7 trillion dollars, more than current global spending on infrastructure: transport, power, water and communications.

Is there any reason why hospitals should own their buildings rather than rent them with long-term contracts? Outside of some historically-significant places couldn't the same be said for most public property. And how do we know whether an army barracks is well-placed if the army doesn't compete with other users over it?

The authors recapitulate their argument in a Citigroup note (pdf), with an introduction by Willem Buiter, going over their case for turning over government property to a properly-managed sovereign wealth fund.

As ever, the ASI is ahead of the curve!

Backing the 1%

I spoke last Thursday in the Cambridge Union on the motion, "This House Believes We Need the Richest 1%." I spoke in favour, giving 6 reasons for my support.

1. The richest 1% feature many people who have provided things to improve our lives.

These include Google, Amazon, Facebook, Paypal, YouTube, etc. We use them regularly and have propelled their developers into the top 1%. They made life easier, more interesting & more rewarding by providing services of value to others. Even the much-derided bankers have made capital work more effectively and made it more available.

2. The richest 1% act as an example to others.

People look at the careers of Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, & Mark Zuckerberg, and are themselves inspired to develop goods and services that will similarly be of use and value to others.

3. The top 1% pay taxes.

In the UK the 1% pay nearly 30% of all income tax. The top 3,000 UK earners pay more between them than the bottom 9 million. Their taxes support schools, hospitals and essential public services.

4. They give to charitable causes.

They are the mainstay of many medical & cultural charities. They fund art galleries, museums & symphony orchestras. They are helping to conquer disease and suffering. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is funding the eventual conquest of malaria, a disease that kills an estimated 2m people annually, including 500,000 children. Warren Buffet has issued the Giving Pledge, for rich people who pledge to give or leave half their fortunes to charity. Hundreds, including Bill Gates, have signed it.

5. The top 1% are early adopters.

They can afford to buy the new gadgets and try out the new processes. The ones that fall short of expectations drop by the wayside, but successful ones go into mass production, fall in price and become generally available. It was the 1% who bought the first large flat screen plasma and LCD TVs that are now commonplace and within reach of most people.

6. The top 1% include those who accelerate the pace of technological advance by putting their money behind adventurous developments.

Paul Allen made his fortune with Microsoft, and put $25m to back SpaceShipOne, winner of the X-Prize for the first private vehicle to carry people into space. Elon Musk made his fortune from Paypal, and used it to fund Tesla because he believes that electric cars can enable a cleaner world. He funded SpaceX, which sends Dragon capsules to the Space Station and is testing ways of landing and refueling its boosters. He does this to speed up accessible spaceflight.

With more time I could have added more reasons, such as the fact that the 1% help create most of the new jobs that replace ones automated or outsourced. I concluded by saying that the 1% help make the world a better, more colourful and more interesting place, and that the goods and services they make available enrich our lives.