Corbyn's economic policy: a critique

What should an economist make of the economic policy of Jeremy Corbyn, the new leader of the Labour Party in the United Kingdom? Among other things, Corbyn and his team have proposed not just a minimum wage but a "maximum wage" as well. That means, presumably, that firms will not be allowed to pay any employees over a certain amount. Unless that amount is set at some extremely high level – so high that it would not be considered a 'socialist' measure at all – the result is obvious. Talented people will leave in order to get higher pay elsewhere, and talented people who might have come to the UK from other places (like high-tax France, for example) won't. Likewise, companies whose business relies on world-class human resources will not be able to attract them in the UK, so will move abroad, or will not bother to come. So unless Corbyn can get the entire world to adopt the same "maximum wage", the policy won't work. And even if he could, there would then be a lot of talented people downing tools.

Another strand of Corbyn thinking is to nationalise (or is it re-nationalise) the energy companies. He might even re-open the coal mines, whose workers caused Margaret Thatcher so much annoyance. Unless the aim is to re-create a labour movement based around mining communities, the latter policy seems odd, for several reasons. First, the UK's coal resources are pretty poor. Thatcher may have had political reasons to close the mines, but the straightforward economic reasons were the low quality of the mineral resource in the UK, and the inefficiency of the UK coal-mining operations. At one point it was cheaper to land coal from Australia in the UK than to mine it ourselves. Were it feasible to mine coal efficiently in the UK, more people would be volunteering to do it. Also, deep-pit coal mining is not, and never will be, a particularly healthy occupation. In a country that is doing its best to stop people smoking cigarettes, it seems remarkable to wish to send more people into coal mines. Unless you figure the entire job can be done by robots, which on the basis of other countries' experience, seems unlikely.

As for nationalising energy companies, why bother? Will that really contribute more to the UK economy? How much more efficiently could the state run the energy sector, even on the most optimistic assumptions? Is the presumed benefit worth the upheaval?

And another point: would compensation be paid to the (millions of) shareholders of the energy companies? If so, that would be a big drain on the government budget: these are big companies so the bill would run to – who can be sure, but probably £200bn or more. What other government budgets are going to be cut to pay that bill? And if no compensation is paid, what signal does that send to potential investors in UK enterprises? Simple: the message that their money could be taken off them without notice. Better, many might think, to put their cash elsewhere. And better, many entrepreneurs might think, not to bother building up a business in Britain.

Corbyn has taken a robust anti-austerity stance. We should borrow to invest in our future prosperity, he insists. The proposition would be more widely accepted, were the UK government's borrowing not already at a record high (apart from war debts) and getting higher each year. Arguably we have not had austerity, we have just kept on borrowing, and spending, perhaps a bit slower than we might have done.

The plan is for 'People's Quantitative Easing'. The argument is, not entirely fallaciously, that the previous rounds of quantitative easing have gone into creating asset bubbles, which is fine for the people who own assets such as shares, but not for the ordinary workers whose firms are finding it hard to meet their wage bills. So how can we get new spending to do the business? Corbyn's answer is to spend it directly on things that matter, things that will improve our lives, things that will makes us prosper in the future – things like roads, housing, transport, green energy and digital projects. In other words, the Bank of England will be creating money that the government will spend on projects that the government decides fit – not to finance the projects that industry and business believe would deliver the best return. The policy certainly envisages a much larger role for the public sector in the economic life of the nation. But is public decision-making any better than private decision-making? Is Whitehall good at prioritising and managing investment projects? Probably not.

The anti-austerity call also comes at a time when the Bank of England is thinking much more about how to tighten things than to loosen them. The UK's growth is already well ahead of Europe's in general, and there are fears that this growth simply reflects the fact that interest rates have been held at 'emergency' levels for more than five years. An important job for a central bank is to dash away the punch bowl before the party gets too raucous and ends in people doing stupid things. Now might be a good time to stop pouring the punch.

How to fund all of the new expenditure envisaged by Corbyn and his team? There is talk about cutting tax reliefs and subsidies to the corporate sector, which the team estimates at £93bn. True, there are far too many little schemes to aid business, all of them squibs injected into the budget speeches of past Chancellors in order to get a cheer of approval from MPs. We would be better to scrap them and have generally lower taxes. But equally, cutting schemes such as grants for research and development might actually, in the immediate term, do more harm than good, forcing firms to cut back their research and investment activities. More thought is needed on that one. And even if the £93bn figure is accurate and not a wishfully high guess, how far does that take us towards paying for the ambitious economic programme that is envisaged?

Another ambition is to 'end' tax evasion and avoidance. A pressure group that the Corbyn team rely on puts the loss to the Exchequer of avoidance and evasion at £120bn. There is no justification for this figure. Surveys generally agree that the UK has one of the world's smallest shadow economies. Certainly, there is a fair bit of back-pocket trading, and when VAT is 20% it is not surprising that many people would prefer to pay in cash than have their transaction go through the books and suddenly grow one-fifth larger in cost. If it were possible to prevent cash transactions (and France has recently lowered the size of transactions where you are actually forbidden from paying in cash), it is entirely possible that a lot of fledgling businesses would be killed off by the tax, and perhaps by the extra regulation of doing everything by the book. But for small transactions, how can the back-pocket method ever be totally policed? The idea that there are £120bn of savings waiting there to be picked off is – well, optimistic.

Likewise with avoidance. True, the Treasury can take action against schemes whereby people are paid in rare metals or some other ruse to avoid national insurance and the like. But the point about avoidance schemes is that they are legal. They work within the existing rules. The more complex the rules are, the more possibility is there of moving money, quite legitimately, from one column to another in order to benefit from the different treatment of it and lower your tax bill. There is really only one solution to this – to have taxes that are low enough that they are not worth avoiding. But that does not seem to be on the Corbyn agenda.

So much for what is in the Corbyn economic programme. Just as revealing is what is not in it. There has been precious little mention of encouraging new start ups, helping growing companies with easier rules and regulations, and promoting entrepreneurship. There has even been ever little talked about improving the conditions for new kinds of company to grow, such as social enterprises, cooperatives or mutuals. The solution to our ills is seen as greater spending led by the state, not a revival of growth, enterprise, trade and entrepreneurship led by ordinary individuals and groups. Given the competition which the UK faces from other, dynamic, economies, this seems a worrying oversight.

In which we praise Jeremy Corbyn for doing the right thing

We do have to admit, this could be the only thing Jezza gets right in his time at the top of the Labour Party but let us praise people doing the right thing when they do it all the same. It is entirely right, just and proper, that the Corbyn for Leader t-shirts were purchased from malodorous sweatshops in Nicaragua and Haiti.

Jeremy Corbyn swept to victory backed by cash raised from the sale of T-shirts made by factory workers earning just 49p an hour. The Socialist firebrand’s fighting fund got a £100,000 boost from the ‘Team Corbyn’ garments, which sold out on his official website. Moments after taking over the Labour leadership, Corbyn spoke of his determination to combat poverty and inequality in an impassioned victory speech.

We too believe in the combat against poverty. And so we do indeed praise Corbyn and his team for doing their bit against such poverty. Their buying their t shirts, and we apologise for our cynicism here, from the global poor will almost certainly do more for said global poor than any political policy they start to mutter about in the months and years to come.

The factories are run by Canadian clothing giant Gildan. In Nicaragua, workers are paid £101 a month for shifts that keep some workers on the factory site for more than 12 hours a day, with breaks. Based on information from workers and their union officials that most employees work 48 hours a week, that works out at 48.5p an hour.

In Haiti, workers are paid a piece rate depending on how many shirts they make – some earning as little as 39p an hour. One woman told us she earns about £20 for a six-day week.

And that's why this alleviates poverty. Because, if people are willing to work in such conditions for such pitiful wages what must the alternative jobs be like in those same economies? Quite, obviously, worse.

As Madsen Pirie of this parish has been known to point out, the best method of global poverty alleviation is for us all to purchase goods made by poor people in poor countries. And thus the purchase of some 1000 or so t shirts from those factories staffed by said global poor in poor countries contributes to the alleviation of poverty.

And so we applaud this action: more people should buy more things from sweatshops after all.

We would also note that in terms of poverty alleviation this might well be the only time that the Corbynistas and Jezzbollah will actually put their own money where their mouths are. But to point that out really would be cynical, wouldn't it?

In which Ha Joon Chang finally jumps the shark

Our attention was drawn to this quite wondrous piece by Ha Joon Chang in the Financial Times:

Bolivia isn’t the only country in Latin America that has defied the Washington Consensus and improved its economic performance. Argentina, Ecuador, Uruguay and Venezuela have all ditched Washington Consensus policies and have seen both accelerated economic growth and reduced income inequality. I am not saying everything is peachy in those Latin American countries. In particular, Venezuela has serious macroeconomic imbalances, although they have improved recently, while Argentina is haunted by its past debt crisis. More worryingly, much of their economic growth has been due to the commodity price boom — fuelled by China’s super-growth, which is coming to an end — rather than industrial development. So there is a serious question about the sustainability of their growth.

However, these countries’ experiences show how the Washington Consensus policies have failed developing countries. That most of the fastest-growing developing countries outside Latin America, such as China, Vietnam, Myanmar, Ethiopia and Uzbekistan, haven’t even adopted Washington Consensus policies in the first place corroborates this observation.

The first point to note is that there's a certain confusion there about what the Washington Consensus actually is. It is, in fact, just a list of stupid things that governments should not do. Although phrased in a positive manner, the real point is don't do the opposite:

The consensus as originally stated by Williamson included ten broad sets of relatively specific policy recommendations:[1] Fiscal policy discipline, with avoidance of large fiscal deficits relative to GDP; Redirection of public spending from subsidies ("especially indiscriminate subsidies") toward broad-based provision of key pro-growth, pro-poor services like primary education, primary health care and infrastructure investment; Tax reform, broadening the tax base and adopting moderate marginal tax rates; Interest rates that are market determined and positive (but moderate) in real terms; Competitive exchange rates; Trade liberalization: liberalization of imports, with particular emphasis on elimination of quantitative restrictions (licensing, etc.); any trade protection to be provided by low and relatively uniform tariffs; Liberalization of inward foreign direct investment; Privatization of state enterprises; Deregulation: abolition of regulations that impede market entry or restrict competition, except for those justified on safety, environmental and consumer protection grounds, and prudential oversight of financial institutions; Legal security for property rights.

The idea that China hasn't followed at least most of that is ludicrous.

As is the idea that Venezuela has been doing well quite frankly.

Yes, we know, Chang has a horror of the idea that markets undirected by the bureaucracy might actually work but really, this is too much.

The real problem with Corbynomics and Peoples' QE

There's a number of problems with this idea central to Corbynomics, this Peoples' Quantitative Easing. It's illegal for a start, being simply monetisation of fiscal policy. It won't work as planned simply because any independent central bank would alter other monetary policy so as to accommodate the change. It's not possible to remove central bank independence because that is again illegal under EU law. And of course there's the killer blow, which is that it was designed by Richard Murphy. We therefore know that it is wrong, we just have to work out why in this particular instance. Allister Heath points to another problem, one that has been occurring to us too:

... financed by “People’s QE”, another of Corbyn’s idiotic schemes. The Bank of England would restart its quantitative easing (QE) programme but instead of buying gilts, newly-minted money would be spent on government infrastructure programmes.

Down that road lies catastrophe: monetising public spending, by eliminating the Government’s budget constraint, frees politicians from the restraints of reality. But the escapism is only ever temporary. If enough money was printed, inflation would make a comeback.

Murphy's answer to this idea that simple monetisation of fiscal policy would increase inflation is to insist that we are all missing the importance of taxation. Yes, true, increasing the money supply would, ceteris paribus, increase inflation. But government could then reduce aggregate demand by increasing taxation. So, there, you see, it all works!

At which point we wonder why the use of the magic money tree in the first place. The end result will be that, to erase the effect upon inflation of the increase in money, taxes will rise. That is, there's no difference here between PQE and the more traditional tax the heck out of the population and get to spend it all on lovely things.

We also have another worry. Which is that we all know that politicians like spending our money like those drunken sailors on shore leave. But the insistence that there's at least some, occasional, relationship between how much they gouge out of us and how much they spend does produce some limit on their profligacy. Remove that limit and let them print whatever they like and, then ask them to raise taxes to stop the resultant inflation. Well, who does believe that inflation will be a sufficient reason for them to raise taxes sufficiently? It's not exactly what has happened anywhere else government has resorted to the magic money tree, is it?

A brief endorsement of 'Markets for Managers'

I'm often asked by people who are just getting interested in economics what they should read. There is no shortage of good 'pop economics' books to recommend to them: Freakonomics is the most famous and The Armchair Economist is enjoyably contrarian, but for my money The Undercover Economist is the most interesting. But none of these teach you the sort of economics you'd learn if you studied economics at a university. And that's where Anthony J Evans's Markets for Managers comes in. It's aimed at 'managers', by which Evans means people who make strategic decisions for their firm, and makes the case that managers who understand the principles of economics will have an advantage over their rivals. But in explaining those principles Evans inadvertently gives an introduction to anyone who wants to learn about them.

The 'applied economics' method that Evans uses is extremely readable. If, like me, you prefer to learn by applying abstract ideas to reality, Evans's approach is ideal. And for British audiences there is something quite nice about reading examples applied to Fernando Torres rather than basketball players I've never heard of. What's most impressive about the book is that Evans even covers the drier parts of economics, like international trade and macroeconomic policy, that the 'pop economics' books don't bother with.

Evans is a Senior Fellow of the ASI and can claim to be one of the UK's only "Austrian school" economists, and these perspectives do shine through, though not to the detriment of the economics being discussed. What he's done with Markets for Managers is to give a clear, interesting and comprehensive primer in economics as it's taught in the classroom. No doubt many managers would benefit from reading it but even more so I find myself recommending it to university students who are not studying economics. For historians and political science students especially, the boot-camp in economics it gives might well give a surprising new way of understanding their own fields.

Economic development can have some old, old, roots

An interesting little piece of research showing just quite how old some of the roots of economic prosperity can be. And shown using the most modern technology as well. For some years now economists have been measuring economic development by the amount of light that can be seen in satellite photographs of an area. For one of the very first things people seem to do, as soon as they can, is to light up that bulb rather than curse against the darkness. The technique has been used to estimate African GDP growth for example, coming to much more cheering results than the official figures would have us believe. And here it's used to measure quite how old some of the roots of successful development might be:

In ancient times, the area of contemporary Germany was divided into a Roman and non-Roman part. The study uses this division to test whether the formerly Roman part of Germany show a higher nightlight luminosity than the non-Roman part. This is done by using the Limes wall as geographical discontinuity in a regression discontinuity design framework. The results indicate that economic development—as measured by luminosity—is indeed significantly and robustly larger in the formerly Roman parts of Germany. The study identifies the persistence of the Roman road network until the present as an important factor causing this development advantage of the formerly Roman part of Germany both by fostering city growth and by allowing for a denser road network.

It's a very interesting little piece of work.

Why are corporations 'socially responsible'

In a 1970 piece in the New York Times magazine Milton Friedman argued that 'the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits'. They should make as much cash as possible for their shareholders, and shareholders should give directly to charity. It is hard enough to be an efficient firm, without needing to be an effective charity at the same time. But it is popularly believed that corporations' role in society does include various other responsibilities rather than simply maximising long term shareholder value. And in real life we note that firms often run charity events, match their employees' charitable donations and so on. Why would firms spend money on charity when they don't have to?

At first you might expect that managers are exploiting the firm to selfishly gain themselves prestige. There is some evidence, for example, that more narcissistic chief executives do more corporate social responsibility.

But the bulk of evidence suggests that firms do better financially when their 'corporate social performance' is higher. A 2003 meta-analysis of 52 papers and 33,878 firms found a positive association—though this was stronger when you measured financial performance by accounting measures rather than investor measures. A 2007 meta-analysis looked at 167 studies and found a similar result: corporate social responsibility is associated with higher financial performance, though quite weakly.

Various different types of study confirm this point from different angles. For example, a 1997 paper looked only at 27 event studies of share prices when firms revealed socially irresponsible behaviour and found the converse of the other results: bad behaviour cut firm value. Event studies on financial markets are quite a good way of isolating causality; with a short enough timescale the change in question is very likely to be the one driving price changes.

But why exactly does CSR help firm performance? Recent work provides some clues. For one, it seems to cut a firm's financial risk. It seems to raise a firm's access to capital. This might be why market analysts tend to recommend firms more in their notes after they engage in CSR. And it explains why firms with more shareholder-driven corporate governance give more incentives to CEOs to engage in CSR—not what you'd predict if it was an agency cost.

This probably comes from reputational improvements, and reputational insurance. Customers prefer to buy from firms who do more and better social programmes, and engaging in CSR seems to cushion stock declines after ethics in business become popularly salient (e.g. after the 1999 Seattle protests against the WTO).

Intriguingly, the reputational advantages may also extend to the government. Davis et al. (2015) discovers that firms who do more nice stuff also lobby more and pay less tax; i.e. that corporate social responsibility and tax are substitutes. This suggests that CSR overall is not driven simply by some measure of manager altruism or empathy or quality—the sort of thing we might usually wonder about. (Though some evidence disagrees.)

None of this really answers whether CSR is good for society at large. If it does enhance reputation, leading consumers to like it more, then this is basically a transfer from consumers to charities. Either way we probably shouldn't lionise firms when they do it—they're just trying to maximise profits, as usual.

Out today: The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics

Released today, The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics (edited by Peter J. Boettke and Christopher J. Coyne) contains contributions from two of our Senior Fellows: Kevin Dowd and Anthony J. Evans. In his chapter, Evans takes an Austrian look back at the causes of – and the lessons we can draw from – the UK's 2007 Financial Crisis. Focusing on regime uncertainty, he rejects both the idea that the crisis was "caused by greedy bankers, complicit politicians, or capitalism itself" and the prominence of analysis that overstates the role of incentives in the run-up to the crisis. Instead, he takes the view (with reference to the work of Jeffrey Friedman, among others) that

There is far more evidence to suggest that it was ignorance and error that caused the crisis and that theoretical issues such as regime uncertainty, big players, recalculation, price naiveté, trading strategies, and corporate governance deserve closer attention.

And that

Allowing insider trading (to improve market efficiency) and reducing barriers to entry and exit (so that foreign banks can provide additional competition) help to thaw the economy and to solve the knowledge problem.

That "ignorance, not omniscience, is the norm" (and a well-functioning price mechanism is the only feasible method by which to ameliorate that problem) is a point too rarely made in reference to the crisis, which is most often blamed on the greed of bankers or the laxity of financial regulations.

As well as being a Senior Fellow of the ASI, Anthony J. Evans is Associate Professor of Economics at ESCP Europe Business School in London and a member of the IEA's Shadow Monetary Policy Committee.

You can buy The Oxford Handbook of Austrian Economics here, visit Anthony J. Evans website here, and download Dr. Eamonn Butler's (excellent) ASI primer on Austrian Economics here.

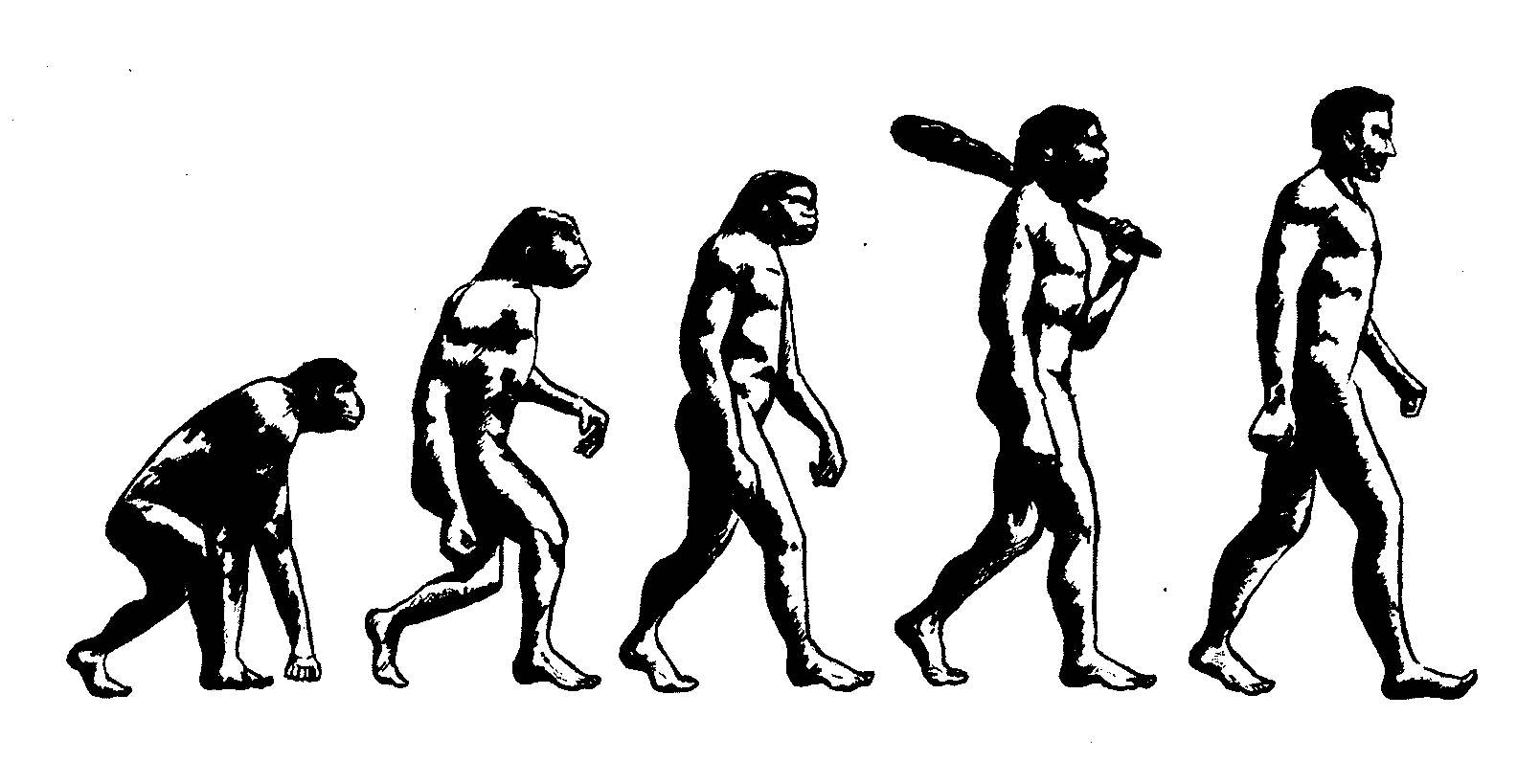

Turning points

There have been turning points in the development of humankind. Some would point to the ability to make fire and the effect it had on people's diet and survival chances. Undoubtedly the development of agriculture about 12,000 years ago and the domestication of grains and livestock enabled humans to become a settled species and to store value against adversity.

For most of the time men and women have been on this planet they have lived a meagre existence at subsistence level, vulnerable to storms, drought and crop failure. Something happened about three centuries ago that changed that for an increasing proportion of Earth's population. It was undoubtedly a turning point when people began to use some of their resources as capital to generate wealth.

Social and intellectual changes played their part in fostering a culture of experiment, innovation and investment. Led by Britain, the Industrial Revolution set humankind on an upward course of wealth creation that has lifted large and increasing portions of humankind out of starvation and misery. The wealth generated by the use of capital has made possible a secure and adequate diet as well as modern medicine and sanitation. It has enabled widespread access to education and healthcare. It has profoundly altered the conditions of life along with the other major turning points.

Capitalism has spread and is spreading its benefits across the world. It is not to Socialism that we owe lifestyles replete with opportunities as well as comforts. By concentrating on the creation of new wealth instead of the mere redistribution of existing wealth, capitalism has set humankind on an upward path of limitless development. In place of envy of those who have more, it provides space or what Adam Smith called "the uniform, constant and uninterrupted effort of every man to better his condition," and of course it applies equally to women.

It seeks not a fairer world but a better one, not equality but opportunity. It works with the grain of the real world rather than attempting to impose a preconceived mental pattern upon it. It works by improvement and evolution, not by revolution. Even though this seems obvious, it is worth repeating from time to time to people for whom this is not so. When people are tempted by the fantasy world of Socialism, it is worth reminding them of the real-world achievements that Capitalism has brought about and Socialism never has and never can.

Taking Corbynomics seriously...and stop giggling at the back there

One of the joys of Corbynomics is that it's all largely the invention of Richard Murphy. We therefore know that it is wrong on any specific subject, we've just got to work out how it is wrong on any specific subject. Which leads us to the idea that this peoples' quantitative easing will be able to replace the private finance initiative. The idea being that if the Bank of England just prints money with which we can do nice things then we won't have to go off and borrow expensively from the hated bankers and kittens will ride sunbeams once again. The problem with this being that PFI really has very little to do with the price of the finance used to build these lovely things. Sure, bankers get their cut of the interest, as do investors, but that's really just not the point of it all. Instead, the point of PFI is to get some people into state run projects who are worried about losing all of their money. That is, it's really about getting equity partners in.

The point of that being that we all know how projects work out if they are funded by the magic money tree. They come in late, vastly over budget and thus waste vast amounts of real resources. And the only way we've ever figured out how to introduce some rigour into the management of these sorts of projects is to make sure that someone is indeed sweating over the idea that they could lose all their money. PFI is thus far more about bringing the strictures of value for money, completion on time and to budget, into public procurement than it is about either gaining the finance to build something or the price that is paid for that finance.

Thus, changing the price paid for the finance doesn't change the argument in favour of PFI at all. Yes, it's superficially appealing to pay nothing to the Bank of England for the finance rather than 5% to hte City, but compared with things like the 276% cost over run of the Humber Bridge it's not the point at all.