Getting educated - like it's the 21st century

Innovative independent institutions are for those who can afford it and the rest will make do with the stagnant state school system: a status quo forthcoming generations should accept no more. An education revolution is on the horizon and Scotland, following its anticlimactic devolution of education, could lead the change. Solutions to the present state have existed for decades and – if actualised – promise to reinvent the way schooling is viewed for good. The rise of ideas meriting attention must coincide with resolved political leadership to eliminate inertia impeding the education model's evolution.

Shuffling taxpayers’ money back and forth between priorities has left us at a dead-end off the path to progress. Free university tuition fees for the wealthiest in Scotland are funded by taxes from the pockets of school-leavers who have gone straight into the job market. College places - the stepping stone to higher education for many young people - have suffered drastic decline after a sudden culling of courses. The Scottish government now funds free school meals for every child, regardless of need, until Primary 3. Meanwhile the poorest are taxed on almost half their income.

Politicians with the guts to be radical in education are scarce but an alternative to spending more money is necessary. Improving the quality of state schools from the heart of government has failed, and when not completely, has failed to achieve anywhere near the success possible if the public had the freedom to choose their schools. This includes, most importantly, having the pick of the private sector’s offerings. The idea is straightforward: individuals choose the best educational options available to them with their own interests in mind. A demand for the best quality schools that inevitably ensues is met on the supply side by a multiplication of the best schools and practices. The poorest schools and outdated methods become null and void, unwanted, and die out faster.

Placing choice in the hands of those the decision affects generally does not fail to deliver the goods. Products, services and technology once only enjoyed by the wealthy are now widespread and accessible for the common man. But education has not evolved like everything else. So rare are independent schools that most of the existing tiny private sector is branded elitist. And so self-deprecating are we encouraged to react to our great educational institutions that the recurring “Should private schools be banned?” debate is taken seriously and considered the only radical option. One day, these leading independent schools, though it will require us to be radical in the opposite direction, could be accessible to the average person too.

School vouchers is the practical policy in which this school choice could take shape. The voucher would be a means of subsidising the child as the consumer; instead of subsidising the state’s provision as happens now. Accountability and efficiency have so far been lost while politicians spend other people’s money on other people’s education. Each voucher would represent the cost of the state educating the child. Of course there are then many ways the policy can be created to cater to various factors and income backgrounds. First proposed by Milton Friedman all the way back in the 1960s, school vouchers have featured in UK Party manifestos but have never come to fruition here.

The mantra of Scotland's current leadership advocates their goal of a fairer Scotland we are all supposed to be striving towards. These are mere words. True fairness is the enhancing of the freedom to choose on the part of everybody. And as it stands this process is not happening. Implementing choice in policy is absolutely imperative as it will not just be conducive to overall improvement of education but it is a tool to innovate and evolve - the key to advancement.

Government loans for master's students is a risky business

The chancellor announced a student loan system for postgraduate master's degrees in the Autumn Statement. Although many have praised the move, it risks doing more harm than good. There are the obvious unintended consequence of encouraging students to undertake courses that aren't in their (or taxpayers') best interest, but here I'll focus on risks to the nascent funding market for postgraduate loans.

It's certainly a popular policy. As the FT reports: "Universities, unions and business groups have reached rare agreement in welcoming new £10,000 loans intended to ‘revolutionise’ the support available for students taking postgraduate degrees." But the devil will be in the detail. Just consider the Student Loans Company, which MPs recently requested face an inquiry following the ‘persistent miscalculation’ of money paid out in loans that will not be repaid. But more important than the wasted money, the government’s intervention in the postgraduate student loan market risks crowding out private sector solutions.

The failure of the Professional and Career Development Loans (PCDL), which are already subsidised by the government through the Skills Funding Agency, is principally due to banks being ill-suited to lending to students (and one the main reasons for this is because of excessive banking regulation). The analogy with SME business lending is the right one – students, like SMEs, are risky and banks are no longer best placed to lend to them.

Smaller and leaner companies can fill the gap where banks fear to tread. As we have seen with Santander’s partnership with Funding Circle in SME finance, the banks know that nimble companies have the skills to plug gaps in the market. In fact, entrepreneurial companies like Future Finance, StudentFunder and Prodigy Finance are already responding to the demand for loans for postgraduate studies.

Whether the bulk of the money comes from peer-to-peer (P2P) investors, alumni or universities themselves, the plurality of the private sector would trump the one-size-fits all approach that the government could take. We are on the verge of the equivalent of the funding revolution we are seeing in SME finance but this intervention risks stymieing it.

All is not lost. The government will consult on how to put the policy into practice and here they have the opportunity to do less harm than copying the PCDL model. As with SME finance, the government could funnel the loans through providers already in the marketplace. And, most importantly, government needs an exit strategy so that we don’t see mission creep and the destruction of a private sector solution.

Philip Salter is director of The Entrepreneurs Network.

Free Education? Don’t make the situation worse!

We love to moan about the system – how it conditions our thought, places expectations upon us, is inflexible and ill-suited to the modern context etc. – and that moaning isn’t limited purely to students. Free education sounds wonderful but, in reality, a subsidised higher education sector works against students’ best interests. The increasing supply of universities, places, graduates, qualifications etc. continuously devalue educational qualifications. With the exception of courses that have a significant vocational content such as Medicine, Engineering, Nursing, Teaching and Natural Sciences, many graduates will find their course’s academic content mostly unnecessary for the line of work they plan to enter. Unfortunately, an oversupply of graduates means that many firms advertise relatively well-compensated occupations as being exclusively ‘grad jobs’. This serves to reinforce the perception that you actually need a degree to even be capable of doing these jobs when, in actuality, it’s just that so many people currently have degrees that it’s pointless applying if you don’t. The necessary skills are better taught outside of a university.

What about all those who would essentially be coerced into going to university because, with free education and the increased supply of graduates, they’d have even less of a chance out there without a degree than they do now? What about those who left education earlier and whose relatively meagre qualifications are further devalued because of more graduates in the labour market? Funnily enough, the income inequality that education subsidies purport to alleviate would only increase. The training required to get a ‘good job’ (and, therefore, to fill them) would simply be lengthened due to qualifications’ devaluation. Normative signposting for how best to spend time is a subtle deprivation of civil liberty.

What is education? Why do we value one form of learning over another? Why stop at higher education? Why not subsidise gap years to Southeast Asia where people ‘discover themselves’? Subsidising one form of education almost always forcefully elevates it to a normatively superior perceived status; this perpetuates social structures, labour market characteristics, outcomes etc. since this normative dimension of legal institutions works to resist our attempts to reinvent social structures and deviating from the accepted norm. Does society really need to pay to offer free behavioural conditioning and thereby limit its own evolution? Free education protests are (mostly) unintended expressions of backward, socially destructive and misery-perpetuating conservatism veiled in social liberalism via equal opportunities and rights rhetoric.

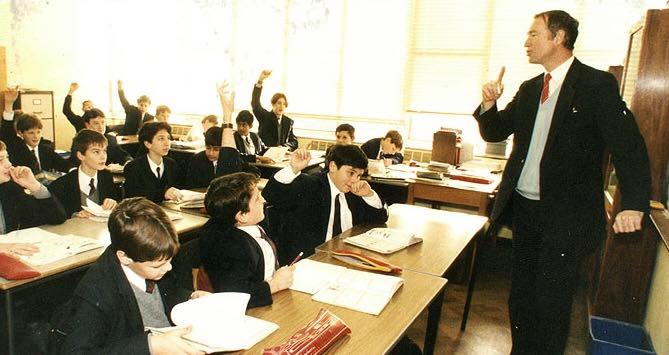

Independent Seminar on the Open Society

Yesterday saw the Autumn instalment of our Independent Seminar on the Open Society 6th-form conference series. Over 260 students from afar afield as Newcastle and Devon descended upon the Emmanuel Centre in Westminster for a day of talks and debate from leading think tankers, politicians and academics. Kicking off the day was the ASI’s own Madsen Pirie, delivering ‘Economics in 2 Lessons.’ Asking students to rank the priority of achieving objectives like clean drinking water, sustainable lifestyles, economic growth in poor countries and an end to ebola, Madsen brought alive the concept of opportunity cost. Moving onto the zero sum fallacy, Madsen explained how so many fail to realise that the economy is not a fixed ‘pie’ to be carved up, and value is created as a result of mutual exchange. The talk provided a solid grounding in how unhindered free trade between individuals makes everyone better off.

Next up was Emma Carr, Director of Big Brother Watch on ‘Civil Liberties in a Digital Age’. Her talk was wide-ranging, highlighting the true extent of state surveillance of individuals, and the actions taken by campaign bodies in response. She also considered the health of the digital economy, looking not only at the impact of surveillance on UK-based tech firms, but the extent to which these companies can manipulate and benefit from our personal data. Considering whether privacy as we know it is dead, Emma argued that it is up to us as members of the public to define the new boundaries, and stressed the importance of good digital hygiene and the use of encryption.

The debate topic for the day was ‘This House Believes That the Living Wage should be mandatory’. Proposing the motion was Deputy Leader of the Green Party Amelia Womack, and opposing it Professor Len Shackleton from the University of Buckingham. Amelia’s argument, peppered with quotes from Churchill and Roosevelt, focused upon the benefits a living wage would bring to local communities and business, and a higher wage floor’s place in a wider re-imagining of society. Len adopted a no-nonsense approach, and laid into the Living Wage’s failings as an anti-poverty measure. The question of age discrimination and equal work for equal pay was also part of a heated discussion. From the floor we saw questions on inflationary pressures, worker productivity and the cost of a Living Wage on small businesses, and despite a passionate performance from Amelia the crowd sided heavily against the motion.

The afternoon saw James Zuccollo, Senior Economist at Reform, ask the fascinating question ‘can fiscal policy make us happy?’ The answer, he argued, is yes. The state can’t really help in areas like family life, but it can help when it comes to issues like unemployment – which causes great unhappiness and declines in perceive self worth – and alleviating economic hardship. James then argued that the government has performed relatively badly on these fronts recently- targeting cuts at the least well-off, whilst protecting comparatively wealthy pensioners. He implored the audience to consider a career in economics, to add balance to the not-so long term economic plans enacted by politicians of all stripes.

To round off the day, Steve Baker MP (bravely!) questioned whether politics was the problem, or the solution. Nobody is satisfied with politics nowadays, but why is that? The problem is not that all politicians are actually lazy, greedy, and corrupt, he argued, but that we expect politics to ‘fix’ so many issues that we’re best placed to solve ourselves. Instead of turning to a distant, central government for guidance on how to live our lives, we should use our own knowledge and compassion to a far greater degree.

Throughout the day the audience was highly engaged, with brilliant questions on subjects from the regulation of bitcoin and foreign policy to reducing the deficit and the rise of UKIP. We also handed over 700 copies of educational, free-market primers to students. ISOS is designed to engage and challenge 6th-form students in a way which compliments the A-level syllabi, and it was fantastic to see such a diverse range of students get involved.

A huge thanks to all our speakers, and the schools and students in attendance who made it such a wonderful event!

There's bad ideas and then there's really bad ideas

And this idea of a Royal College of Teaching falls into the category of really bad ideas:

This time it is from Labour’s Tristram Hunt, in his plan to introduce teacher licensing. The implication is that teachers cannot look after their own standards so the state will have to set them, and police them.

Increasing centralisation: no, that's not what we think the economy needs.

But a solution to this gradual erosion of teacher autonomy, dignity and professionalism may be at hand. For the last two years, teachers and educationalists have been looking at how they might set up a ‘Royal College of Teaching’.

And that's worse. For what it does is centralise how things are taught into the control of the one group of people we don't in fact want to have control of that. That is, the educationalists who have messed up the system already.

As Hayek pointed out, knowledge is local. Yes, that foes mean that we don't want the politicians telling teachers how to do their jobs in detail. We want headteachers, people with actual experience of teaching, to be telling teachers how to do teaching. But not only don't we want politicians describing the details, we also don't want the so-called experts in educational methodologies telling teachers how to teach. Nor the sort of bureaucrats and educationalists who would flock to a centralised body like a Royal College of Teaching. What we want is as above: headteachers working with their teachers to work out what works best in their particular circumstances.

Another way to put this is that centralised control under the politicians would be undesirable: but centralised control under the "experts" with no outside influences would be even worse. After all, who do you think is responsible for the current mess in British teaching? Teachers, or those who have been educating teachers for the past 50 years and who would inevitably be those running the new College?

No, a very bad idea indeed.

The John Blundell Studentships

We are pleased to announce the creation of the John Blundell Studentships. Named after the former Director General of the Institute of Economic Affairs, who died earlier this year, the Studentships are designed to help talented pro-freedom students who are unable to fund themselves for postgraduate work. We aim that this support will help create intellectual ambassadors for freedom among the rising generation.

John was a tireless promoter of the free society and the free economy. An incalculable number of teachers, students, activists, professionals and even politicians were first brought to an understanding of these ideas, and to their own commitment to them, through the work of John Blundell.

This initiative will continue his life's work, of developing minds and ideas, into the future. There is no more fitting memorial. His wife, Christine Blundell, says "John would have been delighted."

More details will be announced soon. In the meantime, we welcome your suggestions, pledges of support and memories of John. Just drop me a line at eamonn.butler@old.adamsmith.org.

Social mobility is increasing but people are unhappy about this for some reason

This an extremely puzzling complaint:

More people are moving down, rather than up, the social ladder as the number of middle-class managerial and professional jobs shrinks, according to an Oxford University study.The experience of upward mobility – defined as a person ending up in an occupation of higher status than their father – has become less common in the past four decades, the study says, leaving children of those who benefited from it with worse prospects than their parents had.

Dr John Goldthorpe, a co-author of the study and Oxford sociologist, said: “For the first time in a long time, we have got a generation coming through education and into the jobs market whose chances of social advancement are not better than their parents, they are worse.”

Social class is not an absolute matter, it is a relative matter. Who is on top can change along with the structure of society: we've had versions where it's the very religious that are on top, where the good warriors are, where those with lots of land are and so on. But while which class it is has changed it's always been entirely obvious that they're of a "higher" class than the others. A relative matter rather than an absolute one.

Given this it is therefore also obviously true that if we've an increase in downward social mobility we must also be seeing an increase in upward social mobility. Because that social class thing is a relative, not an absolute, matter. And normally people cheer, or at least people like The Guardian cheer, when there's an increase in upward social mobility.

Can't think why they're not here.

Foundations of a Free Society wins 2014 Sir Antony Fisher International Memorial Award

I am quite chuffed. My short book Foundations of a Free Society has just won the 2014 Sir Antony Fisher International Memorial Award. Named after the late business and think-tank entrepreneur, goes annually to the think-tank that publishes the study that has made the greatest understanding to public understanding of the free society. That means the $10,000 prize goes to our good friends at the Institute of Economic Affairs, who published it, rather than to the author (sob!), but all power to them. The book was only published last November but has already gone into nine translations plus one overseas English edition.

Previous winners have included the bodies that published such books as How China Became Capitalist, by the Nobel economist Ronald Coase, and Prof James Tooley's hugely influential book about private-enterprise education in poor countries, The Beautiful Tree. So I am in excellent company.

It is a fine example of what can be done when think-tanks collaborate, each doing what they do best in a productive partnership. And I will be there in New York next week, collecting the silverware along with my friends and colleagues from the IEA.

Foundations of a Free Society is designed to explain what a free society is, for people who do not live in one (which is most of the planet, really) and cannot understand how a free society can be made to work. It is written in very straightforward, non-academic language, with no big footnotes and references and all that jazz – the sort of stuff that even a politician could understand.

It talks about rights and freedom and representative government, and toleration and justice and free speech and all the other principles of social and economic freedom. And it explains how and why a free society can run itself, without needing top-down control from some strong, dictatorial government. I hope therefore that it will help get these principles lodged in the mind of the upcoming generation, and give them the confidence to build genuinely free societies in their own countries around the planet.

Download a free copy of Foundations of a Free Society here.

We would rather expect the children with degrees of people with degrees to earn more than the children with degrees of people without degrees

A finding that people who have degrees, and who are the children of people who had degrees, earn more than people with degrees but who are the children of people without degrees, seems to be worrying some people. We rather think that it's a likely, obvious even, outcome of how the country has developed over the decades.

British men earn more if they have a parent who went to university, a study has found.In contrast, men born to lowly educated parents earn 20 per cent less that those with the same qualifications but from a better background.

Researchers at the Institute of Education, part of the University of London, said it proved the wage inequality could be transmitted from one generation to the next.

They studied the salaries and backgrounds of 40,000 men between 25 and 59 across 24 countries, including Britain.

Think through what happened to higher education in the past. From 1950 to 1980 or so it really was only the bright (some 10% of the age cohort) and the rich who went to university. The poor and bright could indeed get there through the grammar school system. After that the floodgates were opened and we now have some 50% of the age cohort going into higher education. We might not immediately think that that should imply a wage premium to those in the current workforce as a result of their parents having a university education but look again. We do know that inheritance is inheritable (it couldn't have risen up out of the primordial slime it it were not) and it's really not a surprise to anyone at all that in the UK wealth and social status are in part also inheritable.

So what we're seeing is that the children of the rich and or bright have higher incomes than the children of the not rich and not bright. And put that way it's not really all that surprising, is it? Whether we want it to be this way is entirely another matter, but it's not actually surprising.

Trying to explain the American academic jobs market

Something's clearly not right about the academic jobs market in the US. The actual process of applying for a job seems to take forever and as one of the more recent Nobel Prizes pointed out such search frictions and inefficiencies do prevent markets from clearing. This is, you know, a bad thing. Further, we've got the fact that American academia is pumping out huge numbers of Ph.Ds who then can't find jobs as tenured professors: but also can't find them elsewhere in the economy as the only thing they've really been trained to do is to try and become tenured professors. They thus end up trying to survive on less than minimum wage as adjunct professors.

So this isn't what we might want to hold up as an example of a successful part of the jobs market. But the question then becomes, well, why is it like this? What's gone wrong?

One possible answer being that this is what happens when you let the left wingers try to run a market. It's not actually much of a surprise to anyone, or at least it shouldn't be, that the US professoriate runs largely leftish. 90% to 10 D to R is the usual number bandied about. It also wouldn't be a surprise to find out that those who do the academic administration tend further left than that: there does have to be an explanation for the various diversity policies around the place.

The end result being extraordinarily strong union protections (that tenure means that, roughly, absent raping the Dean in his office no professor can get fired), vast overtraining of would be market entrants and the majority not actually being able, they being excluded from those union protections, to gain a living. Oh, and the end product becoming ever more expensive as the providers layer themselves with ever more orgies of bureaucracy.

Sounds just wonderful really: or perhaps we might want to use it as a warning. This probably isn't the way that we want the entire jobs market to work so let's not attempt to add more of those job protections, unionisation and so on.