When science tells you something you've got to take the rough with the smooth

We've a lovely little example today of where so many environmentalists go wrong on this climate change thing. As always around here we'll take the IPCC seriously as a matter of exposition of logic. So, The Guardian's running a column in which sure, the IPCC is right about the dangers of climate change, about the way that they prove that something ought to be done. However, they're entirely wrong about what should be done (ie, get markets and private money involved in changing the world) because, well, you know, that's just neoliberal economics and that can't be right, can it?

The IPCC report has done a wonderful job at alerting the global public opinion about the urgency to prevent, or at least limit, climate change. Also, it has correctly identified the growing pressure climate change will put on public finances, thus worsening the crisis of the state. But when it comes to finding solutions, it has not escaped the neoliberal zeitgeist, and especially the tendency to see in financial markets an answer, rather than a source of social problems.

This is indeed a small example of a larger problem. People taking the IPCC seriously on climate change, the need to do something, but then insisting that this means the IPCC supports their own plan for whatever should be done. As, for example, we note around here often enough the Greenpeace and the like plan to move forward into the Middle Ages in response to it all.

Here's the problem with these projections. The very proof that the IPCC uses that something is worth doing, that doing something will be, in the end, less costly than doing nothing, is entirely based on that neoliberal economics. More specifically, that we use the most efficient methods of mitigating climate change (ie, a carbon tax, not any of this regulatory rubbish and most certainly not a retreat to feudalism).

Both William Nordhaus and Richard Tol have done a lot of work on this. Leaving out their differing numbers the logic is: it's worth spending $x to avoid damages of $x or more than $x. If $y is greater than $x then it's not worth spending $y to avoid damages of $x. They both go on to point out, at various times, that the most efficient method of spending to avoid damages is that carbon tax. Thus spending $x in a carbony tax sorta manner can be justified if we're reducing future damages by $x or more. However, because other methods (regulation, law, targets, micromanagement) are less efficient then that is akin to trying to insist that spending $y is worth avoiding damages of $x (where y is still larger than x).

Note that none of this depends upon whether the IPCC is correct in its science about climate change at all. This logic is internal to the system. The IPCC has only, using neoliberal economics, shown that responding to climate change in the most efficient manner possible (ie, using neoliberal economics) is worthwhile. This means that you cannot then project your own desired, less efficient, solutions onto the world using the IPCC as your justification.

So ideas like the one quoted above just don't fly. You can't reject the neoliberalism of the IPCC solutions because they are integral to the argument that anything at all should be done.

Rowan Williams falls into the old climate change logical trap

For someone who trained as a theologian and philosopher this is rather sad: Rowan Williams has, in his retirement, fallen into an all too common logical trap in discussing climate change and what we ought to do about it. His piece is here and that trap is that while it's entirely possible to prove that climate change is a problem that we should do something about (a view largely held here at the ASI) that is not the same thing as saying that because climate change is a problem we should do anything about it. Anything here meaning not that we should do nothing, but that we end up giving credence to the more ludicrous suggestions about what we should do. This is an extremely important point and it's one that is desperately misunderstood too.

OK, so climate change is a problem and we should do something about it. Please, no, let's just take that as a starting assumption for the rest of this discussion. Excellent, does that mean we should follow Greenpeace and abolish industrial capitalism? That would be to embrace the "do anything" option and it would be ludicrous. The costs in human tragedy of starving a few billion of us as we return to an agrarian feudalism would be worse than anything that climate change could possibly foist upon us.

That is, the merits of doing whatever to deal with climate change depend not upon the merits of beating climate change but upon the merits of doing that particular thing.

And that's where this pernicious logical error comes in. That some things might or should be done to deal with climate change is, in our opinion, entirely true. But this does not then mean that every brainspasm that issues from a politician or environmentalist is worth doing due to the threat of climate change. We have to go through each and every suggested action to see whether it does make sense, or not, given the costs and benefits of that action.

The past year has seen the obstacles blocking action on climate change beginning to crumble. Opposition on scientific grounds looks pretty unpersuasive in the light of what has come from the experts on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Their seven-year study states that they are now 95% certain that human activity is a significant and avoidable element in driving climate change around the world. Predicted changes in the climate are now being observed in the most vulnerable countries, confirming the predictive models that have been used.

The suggestion that action on this would have too great an economic cost is likewise looking increasingly shaky.

No, absolutely not. Proof that some action is required, proof even that some actions would be justifiable, is not proof that all actions are desirable or justified. It depends upon the economic cost of each action itself to determine that.

Or, to put it in a shorter and simpler manner. Just because climate change might be real it doesn't mean that the world of Caroline Lucas, George Monbiot or Bob Ward makes any sense. We're not entirely sure that a world that contains Bob Ward makes sense come to that.

David Attenborough has decided to nationalise your garden

Isn't this nice of David Attenborough? He has decided that your garden is no longer your property, for you to do as you wish with, he has decided that your garden, the one that you bought, you maintain and you pay the taxes upon, is now to be used as he wishes:

Nature reserves and national parks are not enough to prevent a catastrophic decline in nature, David Attenborough has told politicians, business leaders and conservationists, saying that every space in Britain from suburban gardens to road verges must be used to help wildlife.

Britain’s leading commentator on wildlife called for a radical new approach to conservation which did not bemoan the past but embraced the changes brought by climate change and a rapidly growing human population.

“Where in 1945 it was thought that the way to solve the problem was to create wildlife parks and nature reserves, that is no longer an option. They are not enough now. The whole countryside should be available for wildlife. The suburban garden, roadside verges ... all must be used”.

In other walks of life we call this theft.

If a wealthy octogenarian wishes to improve the life opportunities of hedgehogs then he can donate some portion of his substantial fortune to St. Tiggywinkles. This naked grab to nationalise (or Attenboroughize) our property for his purposes should not and cannot be allowed to stand.

The entire point of private property is that we get to use it and dispose of it as we wish. You do so with yours Sir David and we'll do so with ours.

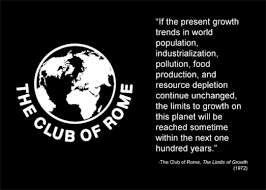

Yes, the Club of Rome and Limits to Growth is still piffle, why do you ask?

Perhaps because The Guardian seems to be giving the piffle another run for its money:

The 1972 book Limits to Growth, which predicted our civilisation would probably collapse some time this century, has been criticised as doomsday fantasy since it was published. Back in 2002, self-styled environmental expert Bjorn Lomborg consigned it to the “dustbin of history”.It doesn’t belong there. Research from the University of Melbourne has found the book’s forecasts are accurate, 40 years on. If we continue to track in line with the book’s scenario, expect the early stages of global collapse to start appearing soon.

Yeah, real soon now.

There's two very basic logical and or evidential flaws in the original study, ones that continue into the various updates that Graham Turner (a physicist, just the person you want to be pronouncing on things like resource availability, eh?) has spent the last few years turning out.

Firstly, they talk about the availability of minerals. And they manage to get this entirely wrong. They start by saying that mineral reserves are x. OK, that's cool enough. Then they compare reserves to annual usage, add a bit for growth in usage as the economy grows and that's fine enough too. They also (and here they're better than many that do this exercise) tell us that of course mineral reserves are not all that matters. There's mineral resources out there too, things we know about that we can convert to those reserves. All of this is fine so far.

Except they then assume (yes, this is a specific assumption they make, one they tell us they make) that mineral resources are ten times mineral reserves. So, if we've got mineral reserves of 30 years then we've got resources for 300: then we run out, civilisation collapses and AIEEE! We! All! Die!

This is complete and total piffle. There is absolutely no relationship whatsoever between reserves and resources. Running from memory here but mineral reserves of potassium are of the order of 60 years or so. Resources are 13,000 years' worth. Reserves of aluminium are around 30 years and resources will last us until the heat death of the universe. There are no reserves nor resources of tellurium anywhere on the planet. Yet we still manage to produce the 120 tonnes a year we use quite happily and can continue to do so for hundreds of thousands of years yet.

There simply is no connection at all between these two definitions of minerals available to us, not in the quantities that belong in each category.

Their misunderstanding gets worse too. It costs a lot of money to convert a resource (something we know where it is, what it's made of, that we can process it using current technology at current prices and make a profit doing so) into a reserve (exactly the same except that we have proven all of these points to certain technical and legal standards). There's a nickel mine out there that is currently producing large amounts of nickel. But it's not making a profit: so the ore that it is mining is still a resource, because it's not been proven yet that the new extraction method is profitable. It's just not a reserve yet even though it is producing. And it's taken $4 billion to get to this point too.

So, if converting a resource into a reserve costs these sorts of sums then people only do it when they're about to start actually mining it. Which means that reserves, for obvious economic reasons, tend at any one point to be some 20-50 years' worth of usage. Why spend $4 billion *proving* something now when you're not going to dig it up for half a century?

Now we can see the piffleness of their assumption. If, for economic reasons, reserves are only say 30 years' worth of minerals then assuming that resources are ten times reserves means that whenever and whatever else you do with your calculations then we run out of minerals in 300 years' time and AIEE! We! All! Die!

The basic assumption that the Club of Rome started with means that, inaccurately, the answer to Limits to Growth is always going to be that we run out of minerals in a couple of hundred years. It's simply not true and it's not true because one of their basic assumptions is piffle of the highest, almost Boris-like, pifflyness.

Turner then makes another hilariously piffly assumption. It's detailed here but essentially he says that we cannot substitute for fossil fuels. We'll not be able to use aluminium, or steel, or silicon, instead of coal and oil:

To account for substitutability between resources a simple and robust position has been taken. First, it is assumed here that metals and minerals will not substitute for bulk energy resources such as fossil fuels.

This is piffle of such magnitude that it ascends nonsense and rises to the level of argle bargle. Consider what is a windmill: it's the use of aluminium, rare earths, steel, concrete, as a substitute for fossil fuels. Solar cells are the substitution of silicon and gallium for fossil fuels. Tidal power is the substitution of concrete and turbines for fossil fuels.

In fact, all renewable energy technologies are the substitution of metals and minerals for fossil fuels.

So, he's telling us that we can't have energy because we can't use renewables and he's also telling us that we don't have enough minerals anyway. But both of these statements are wrong. No, not just mistaken, not arguably a bit extreme, not even well meaning errors. They're out and out fabrications stemming from the piffle nature of the original assumptions. Those two, entirely incorrect, assumptions make the Limits to Growth calculations always turn out this way. That in 300 years' time AIEE! We! All! Die!

Start again with the correct, non-piffle, assumptions, that we've plenty of minerals and we can use metals and minerals to substitute for fossil fuels and all the problems fade away. For if we have metals, minerals and energy then we don't all end up dying (AIEE! etc.) in 300 years' time from a lack of energy, metals and minerals, do we?

I've the notes around to do an entire book on this point but I've never actually bothered to sit down and scribble it out. Surely no one actually believes this piffle anyway so why bother refuting it? I might have to reconsider that.....

And Zoe Williams proceeds to get renewable energy wrong

One of the saddest things in this whole debate about climate change is that people simply manage to get, even assuming that the predictions are correct, the right course of action for the future so wildly wrong. As with Zoe Williams here:

The interesting thing about energy policy, as it comes into focus for the start of manifesto season, is that it gives each party the chance to be dreadful in its own unique way. The Conservatives are going with the line that bills are too high (they are), this is because of Labour’s high taxes (it isn’t), and can be rectified by “slashing green levies”. This is their offer: it makes very little financial difference (an average of £50 a year) and no demands on energy companies except to simplify their bills. It looks like a lot of bluster about the “mess they inherited” paired with some ineffectual flapping.

In fact it isn’t, it’s an extremely bold statement; by casting green levies as expendable, they show they are not serious about transforming the energy market. They’re not serious about renewables. They’re not worried about carbon targets. They’re not going to prioritise investment in green infrastructure. They’re not 100% convinced that climate change is even happening, and – this bit is crucial – they’re not going to do anything to undermine the market dominance of existing companies selling fossil fuels. Only alternatives will challenge the energy oligopoly, and alternatives need investment.

It's that last line that is wrong. But so wrong that it undermines everything else that is being said.

So, let us start from our usual position around here, whether or not you believe it just, for the sake of the argument, work with this for the moment. That the IPCC, the Stern Review, they're all correct. Climate change is a problem, one we're causing and one that we should do something about.

OK, great, what? Well, firstly, as a matter of public policy we've an externality, those carbon emissions, and we should be getting them included into market prices. This is the great lesson from Stern (and he's backed by all other economists who look at the subject, Nordhaus and Tol for example). Super: so, by a fairly inefficient kludge of the ETS, the minimum carbon price and the rest we've managed that. So, on that point we're done. We don't need to be stomping around the country shouting "Invest!" for we've already changed prices to take account of that externality. We're done and dusted: we just need to wait for the effect of that price change to work through peoples' investment decisions over the next few decades.

The second is that point that all of the solar PV boosters keep telling us. That solar power is, if not right now then definitely within the next couple of years going to be, price competitive with fossil fuel derived energy. And as a matter of public policy of course our carbon price has aided in this. So, do we now need to point a wall of "investment" at this technology?

Well, no, no we don't. If, after the carbon tax, solar PV is not price competitive then we don't want to install it. For that tax already includes the future damages the use of fossil might cause. And if it is price competitive then we don't need to "invest" (when someone in The Guardian says invest of course they mean public subsidy) because as it's already price competitive then people will install it anyway as the cheapest option.

Which brings us to a point we've made repeatedly around here. According to the standard works on the economics of climate change we in the UK have already done everything that it is necessary to do. That combination of technological advance in solar plus the public policy of pricing carbon is it: we're done. We simply don't need to do anything else but wait.

The Puritans still don't understand the meaning of the word "waste"

Apparently households are "wasting" as much as £18 a year by continuing to use tumble driers even in the summer months. We're told that we should all be out there hanging the stuff up from a washing line instead. Quite apart from the fact that a British summer is not a period of guaranteed dryness this is showing a depressing ignorance of the meaning of the word "waste" in an economic sense. There is one indication of how much richer we all are now though:

Official statistics show that more than 16.5m UK households own either a washer-dryer or a tumble dryer.

Sales of tumble dryers in particular have soared in the past decade. Almost 12.5m households in the UK owned a tumble dryer as of 2013, an increase of 3m since 2003. By contrast, in 1970 just 138,000 homes owned one.

This is all part of that great economic emancipation of women that has been the signal change of the past two generations. As running a household becomes ever more mechanised then both the gender division of labour and the restriction of women to largely household duties simply fade away. But about that waste:

The declining popularity of the traditional washing line is costing British families at least £120m a year, as tumble dryers are routinely used throughout warm summer months.

More than half of all households who own a tumble dryer use it at least once a week during the summer, according to the Energy Saving Trust.

The organisation, a charitable foundation which offers advice on cutting energy bills, said that a typical household could save £18 from their annual electricity bills “by line drying clothes instead of tumble drying” during June, July and August.

It would be rare to find a household that had a budget constraint that bit harshly on £18. And as to whether the spending of that £18 is waste or not is really up to those spending it rather than some bunch of puritan prodnoses. The actual budget constraint that none of us is ever free from is that on our time. And so the question becomes whether, in the minds of those doing it, the time spent with a tumble drier is worth the £18 as against the longer period of time used with the washing line. We've good authority as to how to measure this in a theoretical sense too. The Sarkozy Commission (including the laureates Stiglitz and Sen) pointed out that such household labour should be valued at the rate for "undifferentiated labour" or, in more understandable terms, minimum wage. That £18 is 3 hours of minimum wage labour. If using a tumble drier saves three hours over an entire summer as opposed to the alternative washing line then it's an entirely rational allocation of time and money. It's simply not waste at all.

Why Roger contradicts himself

Most of us know someone like Roger. His speciality is that he opposes policies that would achieve his objectives, and supports policies that achieve their opposite. Roger supports what he calls 'clean' energy, yet is adamantly opposed to nuclear power which is among the energy sources with lowest environmental impact. He is also among those who protest against fracking, even though the gas it produces enable us to phase out the coal-fired power stations that are more than twice as dirty as gas-powered ones. He argues that fracked gas is a non-renewable fossil fuel, which it is, and is therefore fast running out, which it isn't. Roger feels passionately about the plight of the world's poor, and is concerned that they should not go hungry. Yet he campaigns to ban the genetically modified crops that can aid their farmers with crops that are more resistant to pesticides, drought and salt water, and can produce increased yields with less chemical fertilizers. He expresses his sympathy with children in poorer countries, yet opposes the 'golden' rice modified with vitamin A that can save hundreds of thousands of third world children from death or blindness every year. He supports using food crops to make ethanol, a renewable fuel.

He supports buying locally and campaigns against the 'food miles' that use energy to transport, even though it is by having us buy their products and crops that poorer countries can lift their populations out of poverty.

Roger is worried that greenhouse gases might be heating up the Earth, yet opposes all proposals that might offer technical solutions to this. He is against even an experiment to seed areas of ocean with iron to generate algae blooms, increase fish stocks and sequester carbon. He opposes all proposed ways to sequester carbon, saying it is more important not to emit it in the first place. He wants experiments banned that would spray fine salt water mist into the lower cloud layers to increase their reflectiveness to incident solar radiation.

Roger's argument in the above examples is that they act against 'behavioural change,' which he says is the only solution to our problems. Ways that enable us to solve those problems and carry on as we have, growing richer, miss the point in his eyes because he does not want us to be doing that.

If we were to take the objectives at face value, it would be illogical systematically to oppose the means of achieving them. In the case of Roger, and maybe some others like him, however, I think I detect signs of a deeper, more fundamental motive. At heart Roger is conservative. He dislikes the pace and complexity of modern life, and yearns for the measured rhythm of a simpler life. He has constructed a somewhat fanciful picture of the past which overlooks some of the disease and squalor that accompanied it. Roger wants us all to live more simply because at heart he dislikes change and the unsettling effect it has on people like himself. Those of us who are comfortable with change and the benefits it brings will beg to differ…

Will fracking lead to a UK energy renaissance?

Jared Meyer, policy analyst for Economics21 at the Manhattan Institute, wrote an op-ed for City AM detailing the barriers that still prevent the UK from taking full advantage of fracking:

For the first time in six years companies are able to bid for natural gas exploration licenses in the United Kingdom. The UK became a net importer of petroleum and natural gas last year and domestically-produced natural gas now accounts for only a third of consumption. Prime Minister Cameron’s decision to go “all out for shale” is a welcome sign and will aid in reversing the trend away from energy independence. If done correctly, increased energy exploration will also help the economic recovery gain strength.Three problems still inhibit the UK from taking full advantage of potential gains from fracking. First, the energy exploration permitting process is far too time-consuming. Second, private landowners do not own the mineral rights beneath their lands, leaving them with little incentive to support energy exploration in their backyards. Addressing both these issues will help overcome strong environmentalist opposition, the third obstacle.

This article was originally published in City AM. Read the full article here.

Climate change is three times worse than we thought, apparently

A new paper tells us that climate change is actually three times worse than we thought. For there may be tipping points, catastrophic changes, that cannot be worked back from and this shows that the carbon price should actually be three times higher than it is:

Climate policy aims to internalise the social cost of carbon by means of a carbon tax or a system of tradable permits such as the Emissions Trading System set up in the EU. But how do we determine the social cost of carbon? Do we take everything into account that should be taken into account? Most integrated assessment models (Nordhaus 2008, Stern 2007) calculate the net present value of estimated marginal damages to economic production from emitting one extra ton of carbon caused by burning fossil fuel.

However, global warming has many non-marginal effects on both the economy and on the carbon cycle. Climate catastrophes can occur that lead to sudden flooding, hurricanes, desertification, water shortages, etc. Many of such changes may be irreversible. Other catastrophes such as reversal of the Gulf Stream or sudden release of greenhouse gases from the permafrost lead to a sudden and long-lasting change in the system dynamics of the carbon cycle. Such changes in the system dynamics of the economy and/or the carbon cycle are called regime shifts. When such a shift takes place, this is called a tipping point. Scientists predict that at some point, structural changes will occur with effects that are very difficult or even impossible to reverse. The usual marginal cost-benefit analysis of existing integrated assessment models then puts us on the wrong track. The problem is much more serious than we think.

This argument seems, superficially, to have some legs. However, it doesn't really hold up for their conclusion is:

If the potential tipping point is ignored, our calibration yields, in steady state, a social cost of carbon of $15 per ton of CO2, which is about the same as in well-known integrated assessment models. If the potential tipping point is not ignored, the social cost of carbon increases to $55 or $71 per ton of CO2, depending on whether we take a constant or an increasing marginal hazard rate as a function of the stock of atmospheric carbon. These are big potatoes, we would say. The precautionary returns are 0.6% per year and 0.5% per year, respectively. The need for precaution indeed decreases when emissions are reduced more with a higher tax on carbon.

Splitting the social cost of carbon into the three components provides additional insights. For example, the $71 per ton of CO2 is split into $6 for the marginal damages, $52 for the risk-averting component, and $14 for the raising-the-stakes component. The risk-averting component is by far the largest, and it is clear that ignoring potential tipping points is putting us on the wrong track when discussing climate policy to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

The problem here is that public policy is not based upon a carbon cost of $15. Rather, it's based on the Stern Review result of $80. Which means that we're already doing enough to cover the new findings of this paper.

In fact, we're actually doing too much. The fuel duty escalator has led to us taxing petrol as if the correct carbon price is $160 a tonne CO2-e. The truth is we're doing too much to avert or mitigate climate change even if (or perhaps especially if) we take all of the scientific consensus about the subject entirely seriously.

The solution to climate change killing all the little fishies

News today that climate change is going to kill off all the little fishies off Alaska. The rise in atmospheric CO2 leads to a similar rise in the ocean where it forms carbonic acid and thus reduces the alkalinity of the water making it hard for various species to operate. This ending up with a reduction in fish as the lower parts of the food chain suffer. The part of all of this that we might have difficulty getting our heads around is that there's a known technique to deal with this problem: it's just that the UN insists that we don't use it. Odd that we're not actually allowed to do something that will mitigate both climate change itself and also alleviate one of the effects of it. The story about the fishies is here:

Alaska’s fishing industry could soon be threatened by increasing ocean acidity, says an NOAA-led study to be published in the journal Progress in Oceanography. The acidification is due to increasing carbon dioxide release, which is absorbed by the ocean

Molluscs, such as the aforementioned Red King crab may struggle in acidic water, and find it difficult to maintain their shells and skeletons. As well as this, it has previously been shown in studies that Red King crabs die in highly acidic water, and both it and the Tanner crab grow more slowly in acidic water.

Alaska is particularly threatened by ocean acidification for a number of reasons: cold water will absorb more carbon dioxide than warm water, communities in certain parts of Alaska, namely the South-East and the South-West are reliant on fishing, and there are fewer other job opportunities in these areas than other parts of the state.

OK, is there anything we can do to deal with this?

When a chartered fishing boat strewed 100 tonnes of iron sulphate into the ocean off western Canada last July, the goal was to supercharge the marine ecosystem. The iron was meant to fertilize plankton, boost salmon populations and sequester carbon. Whether the ocean responded as hoped is not clear, but the project has touched off an explosion on land, angering scientists, embarrassing a village of indigenous people and enraging opponents of geoengineering.

The iron did fertilise plankton, there was an algal bloom, fish numbers increased and at least some of that carbonic acid was removed from the local waters, all at the same time. There was even some amount of the CO2 being deposited as nascent rock on the ocean floor and thus it being sequestrated for geologic periods of time. All in all it sounds like a most wonderful technology really, doesn't it?

The project was also on uncertain legal grounds. Ocean fertilization is restricted by a voluntary international moratorium on geoengineering, as well as a treaty on ocean pollution. Both agreements include exemptions for research, and the treaty calls on national environment agencies to regulate experiments. Officials from Environment Canada say that the agency warned project leaders in May that ocean fertilization would require a permit.

Other than this, probably illegal, experiment the last official one was done 10 years ago. It's just great that everyone's working so hard to find even a partial solution to what we're generally told is the greatest problem of our times, isn't it?

We've spoken to one of those who studied, in detail, that last official experiment and there's no doubt that it works, would be extremely cheap and is capable of not only increasing fish numbers but also of sequestering some 1 gigatonne a year of CO2 into rock. But the powers that be won't let anyone actually do it and there are no further officially approved experiments in the pipeline either. It's almost as if people don't want solutions to climate change, isn't it?