Introducing the climate deniers at the Renewable Energy Foundation

John Constable of the Renewable Energy Foundation finds that he gets attacked for being something he is not:

Work like this has caused a flurry of unease in certain circles. REF has been falsely accused of hiding its donors, while our new Energy Institute – established with the University of Buckingham – has been branded a “front” for climate sceptics. The Independent quoted one academic who called me a “doubt-monger”.

We feel the pain, we've been accused of similar things ourselves. So, what is it that Constable suggests?

But it also means that there has to be a clear economic signal, which I think is best provided by putting a consistent, economy-wide price on carbon, probably through a carbon tax with corresponding offsets in other taxation. This would be flexible, so economic harm could be kept under control, and it would be technology-neutral, allowing the economy to gravitate towards the cheapest ways of reducing emissions that human ingenuity can discover.

That is also what we have been suggesting this past decade. And it's extremely surprising to be told that we're climate deniers for doing so. For this was, of course, the major recommendation of the Stern Review itself. That source document that everyone is using to tell us that something must be done. Stick on a carbon tax at the social cost of carbon emissions, reduce other taxes to compensate and she'll be right. Perhaps sprinkle a bit of R&D fairy dust tax money around the place as well.

This is not an odd view, is not some denial, it's the straight up mainstream view. We could get everyone from Bjorn Lomborg through Nick Stern, Bill Nordhaus, Richard Tol all the way out to James Hansen to sign on to this. Yes, there's technical arguments about what the social cost is but the basic structure of what needs to be done is evident to everyone who has spent more than 30 seconds thinking about the economics of this.

But then, of course, it's when the economics profession is most united in their view of a matter that no one else takes a blind bit of notice, isn't it?

An interesting example of how politics works today

True, this example comes from the US, where one of us does some media work and is thus bombarded with press releases. But this really does quite take the cookie, as they might say over there:

NEW YORK – An open letter signed by over 130 faculty members was delivered this morning to NYU President John Sexton calling for fossil fuel divestment. The letter, which began to garner signatures in early February, calls on the university to divest its $3.4 billion endowment from the top 200 publicly traded oil, gas, and coal companies. The university currently has an estimated $139 million in fossil fuel investments.The letter was delivered in hard copy this morning by the Environmental Studies department chair, Dr. Peder Anker, who stated, "NYU needs to divest, because it’s the right thing to do."

Delivering it on paper? Isn't that going to kill trees? However, what interested us was, well, we know pretty much nothing about New York University. This is not a comment about the divestment campaign please note (a silly idea but it's not about that). It's a question about, well, is 130 members of faculty an interesting number or not?

We could imagine that NYU has 140 faculty members. In which case this is highly interesting, even if not important. So, we asked. And it should be noted that this list of 130 includes those at other campuses, associated study groups, remote locations and so on. The answer for the total faculty was:

The latest number I found from 2013 is for "Academic Staff" is 6,564.

We'll assume that Academic Staff is a rough proxy for Faculty shall we? And our rough, back of that fag packet with the cancer warnings on it, calculation is that 2% of the faculty have signed this petition.

From memory, so don't quote us on these numbers, some 11% of Americans are convinced the Moon landings were fake, 18% think that Obama was born in Kenya and, judging from legislative acts, more than 50% are sufficiently deluded to think that raising the minimum wage increases the number of people in employment.

But, this is how politics is done. Some papers will print this release without questioning the numbers and it will become a standard tale that "the faculty of NYU call for divestment". And thus is politics done in this modern age.

Aren't we all such lucky people?

There's gold in them thar sewage plants!

Quite the little story as it seems that the good old British sewage system could be a source of all sorts of lovely metals:

Although the prospect of digging through human excrement hunting for the gleam of gold may seem unpalatable, the figures show it could be a surprisingly lucrative enterprise.An eight year study by the US Geological Survey found that levels of precious metals in faeces was comparable with those found in some commercial mines.

In fact, mining all of Britain’s excretions could produce waste metals which are worth around £510 million a year.

All most interesting and proof that where there's muck there's brass. However, as usual in these sorts of things, that's not quite the whole story.

In the minerals and mining world the crucial distinction is between dirt and ore. Dirt is, well, you know, dirt. It's made up, like all dirt is, of different elements. Sometimes, and here's the crucial definitional difference, that mixture of elements is sufficiently lopsided in favour of one of more elements that it is commercially viable to process it. That makes it ore: dirt is not commercially viable to process, ore is.

So, as an example, the North Sea contains some trillions of pounds worth of gold. And, last time anyone ran the numbers, it would cost some tens of trillions to process the North Sea. The North Sea is therefore dirt, not ore. And so it is with our human sewage. Yes, there would be a revenue stream from processing the metals out. And the cost of doing this would be higher than the revenue.

Meaning that sewage is in fact dirt. Which is roughly where we came in, isn't it?

What joy in The Guardian letters page

Mark Lynas exaggerates a little but is generally correct here:

Climate change is real, caused almost entirely by humans, and presents a potentially existential threat to human civilisation. Solving climate change does not mean rolling back capitalism, suspending the free market or stopping economic growth.

That "potentially existential" is the exaggeration. It's something between not a problem and a large problem. Meaning that yes, we probably would like to do something about it even if only on the grounds of insuring ourselves. Very much the Matt Ridley point in fact (not surprisingly, as the Good Viscount has informed us on the matter and we have been able to inform him on certain points).

Then we come to the Guardian letters page in response to Lynas. Much spluttering that of course capitalism must be defeated etc. And we're also set a challenge:

Immense changes to the economic system must be made over the next few years, and the blame game gets us nowhere. If Klein’s belief that “corporate capitalism must be dismantled’” is wrong, it is up to the right to show how the new measures required can work under the present system.

OK, how's this for a plan?

We carry on rather as we did in the 20th century. Roughly the same rate of economic growth, roughly the same demographics (we need the growth rate to reduce fertility and thus get the demographics), roughly the same rate of globalisation and increase in international trade, roughly the same rate of increases in energy efficiency, reduction in costs of solar and so on and on. There's also that insurance bit and as we've got to get tax revenue from somewhere let's have a carbon tax and reduce the taxes on a good thing. Say, increase the allowance before paying payroll taxes (national insurance for the UK, FICA for the US etc). This will in fact solve the problem. (Maybe we might try to miss out the communism and the two world wars bit though.)

No, really, it will. For what we've described there is A1T, one of the scenarios that the IPCC itself uses to forecast climate change. And A1T really is just a straight line projection of the trends of the last century across the next. The carbon tax is simply adding the major recommendation of the Stern Review to our mix as that insurance policy. Under A1T climate change is not an existential problem, it's not even a major problem. In fact, by the end of the century it's not even a problem at all.

Now, we're generally believed to be on the right so perhaps that answers the letter writer's question? Or perhaps, because this isn't actually an answer from the right but is one from the climate establishment it doesn't qualify?

Or, of course, there's the possibility that all of those shouting about climate change and the necessity of deconstructing capitalism and markets either have not read or have failed to understand the basic documents that lay out the concerns in the first place. That would be something of a pity, of course it would, but it wouldn't be the first time various lefties have decided to ignore reality.

Government grants always end up doing this: so let's not have government grants

We don't share the reason why these people are outraged but we do share the outrage:

Snack food and confectionery companies, including Nestlé and PepsiCo, are paid substantial government subsidies to help them make products that will damage the nation’s health, according to charities involved in heart attack prevention and obesity.

Mondelez, which split from Kraft and owns the Cadbury’s brand, was given nearly £638,000 by Innovate UK – formerly known as the Technology Strategy Board – from 2013 to 2015 to help the multinational giant develop a process to distribute nuts and raisins more regularly in its chocolate bars.

Nestlé received more than £487,000 to invent an energy-efficient machine for making chocolate, while PepsiCo was awarded £356,000 to help develop new ways of drying potatoes and vegetables to make crisps.

Given that people seem to like chacolate and crisps if taxpayers' money is going to be splurged on food companies then it might as well be on food that the taxpayers enjoy. So, to that particular criticism we offer a heartfelt "Meh".

Our outrage is concentrated upon the splurging and waste of taxpayers' money. Even, perhaps, the illogic of the attempt to defend it:

Innovate UK says the money is to make the companies’ food processes more energy-efficient and reduce their carbon footprint. In the case of Mondelez, for instance, a better way of distributing nuts in chocolate bars would mean that fewer nuts have to be bought by the company, reducing the amount of transportation used.

“The goal of the projects highlighted was to help reduce emissions and water usage in food processing,” said a spokesman. “These large firms produce a lot of food, which uses a lot of energy, so to make a difference we need to work with those large companies to help reduce their carbon footprints.”

The UK does now have a system that largely approxiamtes to a carbon tax. Therefore those carbon emissions are already internalised in the decision to transport or not transport more nuts. What this means is that the provision of a grant is in fact a complete waste of money, a reduction in the general wealth of the human species.

Think it through this way. Reducing the number of nuts purchased and or transported might well reduce the costs to the chocolatier. Against which are the costs of reducing those purchases and transporting. Only if the benefits of less purchasing and transporting outweigh the costs of doing so is the process as a whole value generating and wealth enhancing. The company itself, as a profit making institution, looked at this and decided it was not. Thus the requirement for the subsidy to get them to do this. That is, the very fact that there is a subsidy proves that (because, as above, the emissions costs are already internalised) this is wealth destruction.

The point and purpose of our paying taxes in order to stimulate innovation in the UK is not for the orgainsation spending the money to make us poorer in aggregate. Therefore let us abolish this organisation which is making us all poorer through its actions.

Who knew? Property rights protect the environment?

Something to put into our "Cor, Blimey, I never knew that Guv'" files.

As the hunting industry has grown, so have the numbers of large game animals that populate South Africa’s grasslands. In other parts of Africa, including Kenya and Tanzania, the opposite has been true: Large mammal populations have been decimated as farms and other human activities encroached on wild areas. But South Africa is one of only two countries on the continent to allow ownership of wild animals, giving farmers such as York an incentive to switch from raising cattle to breeding big game. ‘‘My first priority is to generate an income from the animals on my land, but conservation is a by-product of what I do,” York says.

Or perhaps this should be in our file marked "Blindingly obvious things that everyone should know".

The way to make human beings preserve something is to make the preservation of that something valuable to said human beings. If people are allowed to own the big game on their property, and also to monetise that ownership, then there will be more big game in those places that allow such practices. Thus, if you desire that there should be more big game you should support private property and the hunting of it.

After all, the private ownership of cows by farmers has not created a shortage of cows, has it?

And this speaks to that problem over elephants too, does it not? Elephants are valued for their ivory. Currently it is not legal to trade in ivory: meaning that elephants have no value except to those who will and do flout the law on ivory trading. Allowing ivory to be bought and sold would lead to the farming of elephants for their ivory. And thus more elephants.

So, what do people want? The moral purity of not allowing ivory to be sold or more elephants?

George Monbiot does rather misunderstand things

The latest bright idea from George Monbiot is that we must, in order to beat climate change, force people to leave fossil fuels in the ground. On the basis that it is necessary to attack supply as well as demand:

Imagine trying to bring slavery to an end not by stopping the transatlantic trade, but by seeking only to discourage people from buying slaves once they had arrived in the Americas.

It's an interesting example of his faulty logic. Because of course the transatlantic trade was at first banned in 1803 and then gradually extended to non-British ships and so on. But slavery lasted in the US until 1865 and into the late 1880s in Brazil, long after that supply was both legally and effectively banned. The solutions were variously more and less bloody but they were actually that people were dissuaded from purchasing slaves rather than that people were dissuaded from supplying them anew from Africa.

So it is, we're sorry to have to say, with fossil fuels and their associated emissions. We are not all victims of the evil capitalists (and, given that governments actually own the vast majority of fossil fuel reserves and resources, it's definitely not the capitalists to blame) who are forcing us to use such fuels. Rather, we the people rather like what we can do with such fuels: travel, heat our homes, heat our food and so on. It is the demand that needs to be changed (assuming that you want to consider climate change to be a problem), not the supply.

After all, banning the production of psychedelic drugs has proved so successful hasn't it? So too the supply of prostitution services where such is illegal. It really is worth recalling that while Say's Law (that supply creates its own demand) might not be entirely true the opposite, that demand calls forth supply is.

The answer to climate change, as above assuming that you think it is a problem and one that needs a solution (we do, even if not as immediate and cataclysmic as Monbiot does), is as it always has been. Either cap and trade or a carbon tax, plus research into non-CO2 emitting forms of energy production, in order to curb demand. Just as Bjorn Lomborg, the Stern Review, William Nordhaus, Richard Tol and everyone else who has actually looked at the economics of the problem has concluded.

Two interesting little points about climate change

Two little snippets that caught our eye. The first:

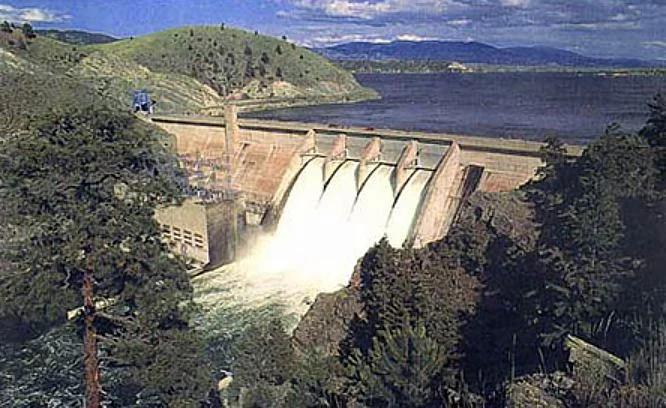

Percentage of annual net electricity generation by renewables in 1948: 32

Percentage of annual net electricity generation by renewables in 2005: 11

The main difference of course is the fall in the relative import of hydroelectric power.

Two months after the floods, while delivering the final order on a long-running case against the 330 megawatt Srinagar hydropower project on the Alaknanda, the supreme court issued a moratorium on dam construction in the state. It wanted an expert committee to investigate if dams in the state caused environmental degradation and exacerbated flooding and review 24 hydel projects on the Alaknanda and Bhagirati rivers that the wildlife institute of India had vetoed for causing irreparable ecological damage. These dams, with a combined capacity of 2,900 megawatts, need nearly 10,000 hectares (24,710 acres) of land and will submerge 3,600 hectares of forests.

Renewable energy is good we are told these days. But we are also told that renewable energy is not good. There's a certain desire that these people make up their dam minds.

Either climate change is the most severe threat to us all, in which case build the dams, or it isn't, in which case we can worry about a few thousand acres of forest. But one of other of these concerns really does need to have primacy.

Anything else would simply be a conversation of the dammed.

Questions in The Telegraph to which the answer is no

Sometime we are asked question to which the answer is obvious:

Is the answer to Britain’s problem of how to revitalise the North Sea creating a new national oil company?

No.

The justification offered for this bizarre idea is as follows:

Given the harsh new realities of attracting the right kind of investment into the North Sea now could be the right time to revive the idea of a new British National Oil Company. This would help to fill the void that is left as companies like Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, BP and Total gradually start to moderate their investment in the region.

Well run, technologically superb, profit seeking companies are leaving the North Sea. Thus we should substitute a state managed (for which read "not well run"), technologically naive because it is new, and not necessarily profit seeking company to try to exploit the same assets.

It's not going to work, is it? Throwing the state and bureaucracy at something not deemed profitable does not suddenly make the state's activities profitable. And we really do want our tax money, if it is to be invested in industry at all, to be invested in things that make a profit. To do otherwise is to make us all poorer.

The correct action in the North Sea is to, as we have been all along, capture the resource rents through taxation and ten leave well alone. If the best people in the world think it's worth exploring or extracting oil under such circumstances then great. If they think it's not worth it then so be it. Having investment decisions made by the Treasury is not going to improve matters here.

If it's difficult to attract the "right sort of investment" then perhaps the right sort of investment is none?

The amazingly stupid way the government subsidises renewables

We've been complaining about this for a number of years now. In fact, we've been complaining about it ever since Ed Miliband lit upon this policy. The manner in which the government subsidises renewable energy projects is, quite frankly, insane:

Two offshore and 15 onshore wind farms have won subsidy contracts in the Government’s first competitive green energy auction, significantly undercutting the prices that have been handed to other projects.The results of the auction suggest consumers may be paying hundreds of millions of pounds a year too much on their energy bills because ministers previously allocated subsidies without competition, providing much higher returns to investors, critics said.

More generous subsidy schemes should now be reined in and excess subsidies clawed back, they added.

In total on Thursday ministers gave the go-ahead to 27 green energy projects, with estimated lifetime subsidy costs totalling £4bn.

Energy companies were forced to bid against each other in “reverse auctions” with the cheapest proposed projects in each category being awarded subsidies.

There's part of the insanity. For a decade and more they have not been insisting upon competitive bids. Instead, they've drawn up standards for certain technologies and then agreed a level of subsidy. That's madness.

But sadly, it gets worse. They are offering different levels of subsidy for different technologies. As we've long said that's where it tips over into insanity.

Start from where the government actually is: climate change is happening, we're causing it and we've got to do something about it. That something obviously being reducing emissions by having renewable power supplies. So, what's the best way of doing this? A series of committees deciding who gets to be the lucky recipient of a cheque? Different amounts of subsidy for different ways of achieving the same aim, reducing emissions by x tonnes?

No, of course not. The correct way to do it is to set just the one price (perhaps a subsidy, perhaps a carbon tax) and then see which technology can best achieve that goal, that reduction in emissions. If, for example, solar can meet the target better than wind then wind should have no subsidy and solar all of it. If onshore wind is better than offshore then no subsidy to offshore, all to onshore.

For we don't in fact want to have just competition among providers of one technology. We want to have competition among all providers of all potential technologies so as to find out which one solves the problem best.

Whatever one thinks about climate change itself the way that the government has been splashing around our money is simply mad. Yes, under both Labour and the Coalition.