Somewhat ghoulish but interesting all the same

Another one of those reports telling us of the terrors of inequality:

The death rate among preschool children in the UK is almost double that of Sweden, with social inequalities being partly to blame, according to researchers.

We have to say that we're not convinced. We could imagine poverty contributing to such things, but simple inequality we have a hard time believing.

The researchers found there were 614 deaths per 100,000 of the under-fives population in the UK, compared with 328 in Sweden. The primary causes of death in the UK were problems associated with premature birth, congenital abnormalities, and infections, with the mortality rate for the first of these factors being 13 times higher than in Sweden.

The study’s co-author Imti Choonara, emeritus professor at Nottingham University’s academic unit of child health, said: “The major cause of death is prematurity, and social economic inequalities are one of the causes [of prematurity]. A society with large inequalities inevitably results in worse health outcomes.”

But they're adamant that it is that inequality. Which is interesting because other studies of premature birth and survival rates don't think that's it at all.

Rather, they think that the Swedish health care system, despite it costing about the same as the NHS, is rather better at dealing with all of this than the NHS is.

That is, the usual finding on this subject is that the NHS isn't very good. Bit of a surprise that, isn't it?

If you think for profit health care is expensive wait until you see not for profit...

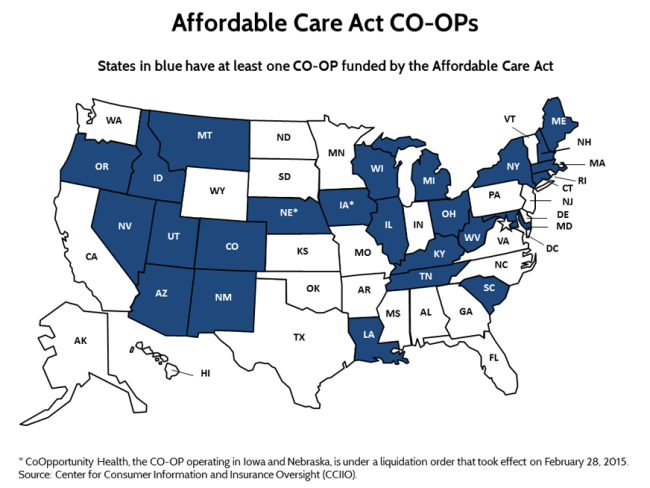

One of the battle cries during the set up of the ACA, aka Obamacare, was that for profit health insurers were way too expensive. Because, you know, profit. It's obvious to all that the profit must make things more expensive, innit? So, a series of cooperatives to provide that health care insurance were set up. There's two problems here. Much as we love cooperatives ourselves the obvious feature of hem is that they've not got any capital. They thus need to grow into a market position rather than just leap into trying to be a large player in a capital hungry industry like insurance. For their capital comes from retained earnings, rather than having some capitalists providing capital: that's rather the point of them. That these coops did try to leap in and become large players in a capital intensive market means they're all going bust.

Nonprofit co-ops, the health care law's public-spirited alternative to mega-insurers, are awash in red ink and many have fallen short of sign-up goals, a government audit has found.

Under President Barack Obama's overhaul, taxpayers provided $2.4 billion in loans to get the co-ops going, but only one out of 23 -- the one in Maine -- made money last year, said the report out Thursday. Another one, the Iowa/Nebraska co-op, was shut down by regulators over financial concerns.

The audit by the Health and Human Services inspector general's office also found that 13 of the 23 lagged far behind their 2014 enrollment projections.

The probe raised concerns about whether federal loans will be repaid, and recommended closer supervision by the administration as well as clear standards for recalling loans if a co-op is no longer viable. Just last week, the Louisiana Health Cooperative announced it would cease offering coverage next year, saying it's "not growing enough to maintain a healthy future." About 16,000 people are covered by that co-op.

Wise observers like Dennis the Peasant were predicting that this would happen. But they're also not cheap:

Separately, the AP used data from the audit to calculate per-enrollee administrative costs for the co-ops in 2014. It ranged from a high of nearly $10,900 per member in Massachusetts to $430 in Kentucky.

Wouldn't everyone prefer a few rapacious capitalists trying to rape the citizenry for profit than admin costs per scheme member of $10,900 a year? Further, can you actually imagine a for profit company allowing bureaucracy to balloon out to such an extent?

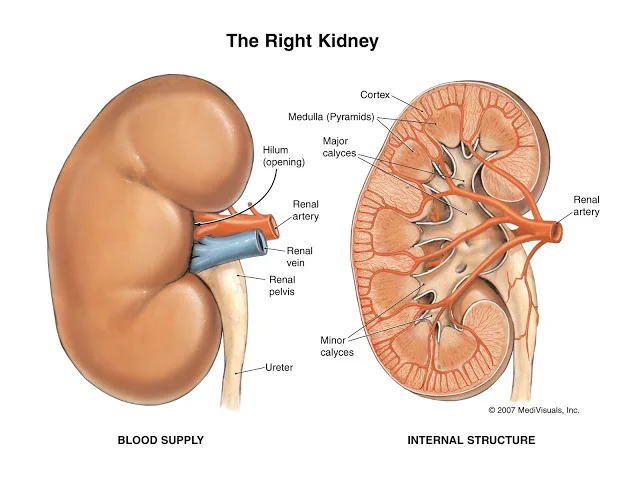

Yes, we really do need to start paying kidney donors

We have long been pointing out that the solution to the shortage of kidneys available for transplant is to offer to pay those donors who might be willing to donate one. Adter all, it's not exactly a new insight that increasing prices brings forth more supply. And the sort of levels of payment necessary are in fact cheaper than the cost to the NHS of dialysis. The New York Times has a nice piece on how this works elsewhere:

Iran’s system has many deficiencies — not least that the very idea clashes with ethical norms observed in many other countries — and the program varies greatly from region to region. But its chief advantage is this: People who need kidneys get them rapidly, rather than die on the waiting list.In the vast majority of cases, donors know in advance what they will be paid and receive appropriate screening and good medical care before and during the operation. And by getting patients new kidneys instead of keeping them on dialysis, the society saves a lot of money and avoids much misery.

Whatever anyone's doubts about whether people ought to be paid for organ donation there's no doubt that it does actually work.

“We should ask ourselves why some people find accepting money to donate a kidney and save a life repugnant, but accepting money for being a policeman or miner or soldier — all of which are statistically riskier than donating a kidney — is O.K.,” said Mohammad Akbarpour, a research fellow in the Becker-Friedman Institute of the University of Chicago. “Is there a fundamental difference?”

It could be that people simply don't understand how low that relative risk is.

Commercializing kidneys calls up images of a filthy, makeshift clinic, a rich traveler with a wad of cash, a desperately poor donor tricked into selling an organ, and a broker who keeps 90 percent of the money. India, Pakistan, the Philippines, South Africa and Indonesia, among other countries, are known for this type of trafficking in organs, and wealthy Americans, Israelis and Europeans are known for buying them.

But in Iran, the legal market pre-empts these abuses. To prevent kidney tourism, recipients in Iran have to share the nationality of their donors, and Iran recently banned kidneys for all foreigners except refugees in Iran from Afghanistan. “The rate of people who die in surgery is much, much lower in Iran than in other developing countries — all the transplants are under supervision,” said Farshad Fatemi, an assistant professor of economics at Sharif University of Technology in Tehran, who studies the kidney market. “If this regulated market weren’t in place, we might have organ trafficking here. We might be more like India or China and have illegal clinics, a black market where nobody looks after patients and donors.”

And there we have something that we have again been saying repeatedly. Markets are going to exist where human desire is great enough. It happens with sex, it happens with drugs, it is happening with organ transplants. In all three we argue that said market will be safer, will work better, if the activity itself is legal so that regulation, if that's necessary, is possible. Insisting that these things are illegal is part of what makes them so dangerous.

So, given that we've got the example of the one and only place in the world where people do not die waiting for a transplant, when are we going to institute our own paid market in them? For it really is true that people die, in great pain, each and every year simply because of some squeamishness about introducing filthy lucre into the proceedings.

As ever, there really are some thing so important that we must have markets in them.

To solve the organ donation problem

Once again we've got the medical trade telling us that more lives could be saved if only more people would donate their organs. We agree entirely that more lives could be saved (and significant sums of money saved too) if more organ transplants took place. But the solution is, at least in part, to purchase organs for transplant, not to continue to rely upon the gift economy.

New statistics released today in the annual Organ Donation and Transplantation Activity Report shows the number of transplants has decreased from 4,655 last year to 4,431 in 2014/15. This is a five per cent decrease on last year and means that 224 fewer people received an organ transplant. At the end of March 2015, there were 6,943 patients on the transplant waiting list with a further 3,375 temporarily suspended from the list, because they were too ill to survive the operation. The NHS Blood and Transplant service is calling for everyone in the UK to discuss organ donation with their family so that they are aware of their wishes.

Of that four and a half thousand transplants, some 3,000 were kidney transplants. And obviously there's not much chance of a live donor offering a heart transplant, but both kidney and liver (and obviously bone marrow) can be done from a live donor. And the obvious way to encourage more people to offer organs while they are still alive is to pay them to do so.

This would save the NHS considerable amounts of money too: a kidney transplant is expensive, yes, but it's cheaper than dialysis over any significant period of time and those with those transplanted kidneys tend to survive a decade or so.

It's worth noting that there's only one country in the world that doesn't have a backlog of people on f#dialysis, dying as they wait for a scarce kidney. That's Iran. It's also worth noting that there's only one country that has paid live donation of kidneys. That's Iran again.

No, there's not a line of people hawking their bodies outside the clinic: the government pays a set fee for a donation on the grounds that, as above, it's cheaper to do that than pay for the years of dialysis. So, given that this is a system that works, saves lives and money, we should be doing it.

And as we so often point out around here, there are some things that are simply too important for us not to have markets in them.

From the Annals Of Really Bad Science Journal

This is simply terrible:

Imposing a minimum unit price for alcohol leads to a dramatic fall in drink-related crime, including murders, sexual assaults and drink-driving, a new study shows.

Crimes perpetrated against people, including violent assaults, fell by 9.17% when the price of alcohol was increased by 10% over nine years in the Canadian province of British Columbia. Motoring offences linked to alcohol, such as killing or injuring someone with a vehicle and refusing to take a breath test, fell even more – by 18.8% – the study found.

An interesting finding but how good is the science?

Method: A time-series cross-sectional panel study was conducted using mixed model regression analysis to explore associations between minimum alcohol prices, densities of liquor outlets, and crime outcomes across 89 local health areas of British Columbia between 2002 and 2010. Archival data on minimum alcohol prices, per capita alcohol outlet densities, and ecological demographic characteristics were related to measures of crimes against persons, alcohol-related traffic violations, and non–alcohol-related traffic violations. Analyses were adjusted for temporal and regional autocorrelation.

Results: A 10% increase in provincial minimum alcohol prices was associated with an 18.81% (95% CI: ±17.99%, p < .05) reduction in alcohol-related traffic violations, a 9.17% (95% CI: ±5.95%, p < .01) reduction in crimes against persons, and a 9.39% (95% CI: ±3.80%, p .05). Densities of private liquor stores were not significantly associated with alcohol-involved traffic violations or crimes against persons, though they were with non–alcohol-related traffic violations.

So, they examined minimum alcohol prices and traffic violations in British Columbia. What did they not measure? Changes in traffic violations in Canadian society in general. In, perhaps, areas that did not have the rise in minimum pricing.

For all the ordure that it thrown at economists and their models these days at least this would never be published in an economics journal. Because the first reviewer, heck, even the editor pondering whether to send it out for review, would first ask, well, what was that general change so that we can measure the effects of this specific change against it?

Not that we're about to do that detailed analysis, we'll leave that to the excellent Chris Snowdon over at the IEA. But an indication from Canada's 2010 crime statistics:

In 2010, police reported about 84,400 incidents of impaired driving (Table 4). The number of impaired driving offences reported by police can be influenced by many factors including legislative changes, enforcement practices (e.g. increased use of roadside checks) and changing attitudes on drinking and driving.

The 2010 rate of impaired driving was down 6% from the previous year, representing the first decrease in this offence since 2006 (Chart 14). The rate of impaired driving has been generally declining since peaking in 1981.

No, we don't know but we've got at least a definite impression. Booze related driving incidents have been declining in general for 30 years. To the point that in the final year alone of this paper's measurements they actually declined nationwide by 6%. And they're trying to pin an 18% decline over a decade on a minimum price change that only happened in one province?

And they don't compare the declines in that one province with other provinces?

This might be all sorts of things but it ain't science, is it?

These people are insane

Yet more from the anti-smoking fanatics:

Smoking costs the NHS at least £2bn a year and a further £10.8bn in wider costs to society, including social-care costs of more than £1bn, says the document. With the public health budget now set to lose £200m a year, the group says that the tobacco industry should pay an annual levy to offset those costs and assist with the effort of stopping young people picking up the habit as well as helping smokers to quit.

Peter Kellner, chair of the report’s editorial board and president of YouGov, said: “The NHS is facing an acute funding shortage and any serious strategy to address this must tackle the causes of preventable ill health.

“The tobacco companies, which last year made over £1bn in profit, are responsible for the premature deaths of 80,000 people in England each year, and should be forced to pay for the harm they cause,” he said.

Sigh, the tobacco companies do not cause that harm. Smokers, voluntarily, cause that harm to themselves and pay taxes through the nose for having done so. And yes, this is a liberal issue. We get to ingest as we wish, we get to kill ourselves with our habits if we so wish because we are free people.

But what raises this to insanity is that the most successful smoking cessation product anyone has ever come out with is the e-cigarette, or vaping. And those very same public health bodies are behind the move to ban the use of such things in Wales. Our apologies, but that really is insane.

We look forward to the next two NHS efficiency reports

Lord Carter's report that the NHS is not in fact as efficient as we would like that august organisation to be. This has led to the predictable cries from the left that it must be the nascent market in said NHS that is to blame:

The aim is, apparently to save up to £400 million for the NHS by making more effective buying decisions that will reduce the product range used by NHS hospitals from more than 500,000 items to just 10,000.

Three thoughts follow. The first is that it is very obvious that Lord Carter is saying that splitting the NHS into hundreds of trusts each making their own buying decisions is hopelessly inefficient, as was always obvious.

Second, he is saying that if you create an inefficient system where cooperation is not allowed because that is contrary to the dogmatically imposed idea that competition produces optimal outcomes you will end up with excess cost.

And third, he is saying that imposing centralisation on the system could save a great deal, as I argued on this blog only last week.

At which point we think we'd like to see proof of the contention.

NHS Scotland and NHS Wales work under very different levels of competition and market outsourcing than NHS England does. There are two possibilities in the Carter report. The first is that the 22 trusts chosen to be examined were from all three systems. At which point it should be possible to pull out the evidence that less market based systems are more efficient, as is alleged. Or, alternatively, the 22 trusts were only from NHS England in which case everyone is, no doubt eagerly, preparing for similar investigations, under the same terms, to be undertaken into NHS Wales and NHS Scotland so as to prove the contention.

For of course those making such a claim would actually like to have solid evidence of said claim, wouldn't they? We'd not want to be deciding something of such public importance merely on the grounds of pure prejudice, would we?

Would we?

So, err, could anyone point us to those calls for or that store of comparative evidence? Because we can't see them anywhere.....

Yes, we've said 'competition' and 'NHS' in the same sentence

There are certain ‘danger words’ you’re not supposed to use when talking about the NHS. These include ‘privatisation’ and ‘competition’. Usually it doesn’t really matter if you’re prescribing something or not; the mere use of the word leads to total destruction (i.e. a lot of yelling and inaccurate statistics thrown around about America). Perhaps the usual absence of these words explains why the NHS continues to fall short in international rankings, and received a below-average DEA score from the OECD, even when compared to similar, publicly funded and run healthcare systems.

But a new report from the Economic and Social Research Council has dared to mention the unmentionable – and as it turns out, competition is key to bettering public hospitals, from management practices to patient outcomes, including mortality rates:

The report The Impact of Competition on Management Quality: Evidence from Public Hospitals, building on ESRC-funded research, shows that hospital competition can improve healthcare by improving the quality of management practices. The research measured the management quality of 100 public hospitals through a management survey of clinicians and managers, and used data published by the government to assess the performance of NHS hospitals in England.

Key findings • Hospital competition is useful for improving management practices and outcomes in healthcare. • More hospital competition leads to improved hospital management and higher hospital performance in terms of quality, productivity and staff satisfaction. • Management quality is linked to improved indicators of hospital performance including clinical quality, mortality rates and staff turnover rates. • Hospitals with higher management scores also had shorter waiting times, lower MRSA infection rates and performed better financially.

This report will probably come as a surprise to many, but only because competition is not allowed to be part of the debate.

The DEA scores I mentioned above: when comparing publicly funded, publicly run systems, some countries actually do quite well. Norway and Italy have high DEA scores, and Poland ranks above average; but in all three cases, there is more choice among providers. (The OECD actually flags up how restricted choice is in the UK.)

I’m not crying ‘correlation equals causation’ here (Sam and Ben would kill me) – but this new research only adds to the evidence that competition in the healthcare sector – public or private – might not be such a terrible thing to bring up after all.

A blanket ban on psychoactive substances makes UK drugs policy even worse

It is a truth under-acknowledged that a drug user denied possession of their poison is in want of an alternative. The current 'explosion' in varied and easily-accessible 'legal highs' (also know as 'new psychoactive substances') are a clear example of this.

In June 2008 33 tonnes of sassafras oil - a key ingredient in the production of MDMA - were seized in Cambodia; enough to produce an estimated 245 million ecstasy tablets. The following year real ecstasy pills 'almost vanished' from Britain's clubs. At the same time the purity of street cocaine had also been steadily falling, from over 60% in 2002 to 22% in 2009.

Enter mephedrone: a legal high with similar effects to MDMA but readily available and for less than a quarter of the price. As the quality of ecstasy plummeted (as shown by the blue line on this graph) and substituted with things like piperazines, (the orange line) mephedrone usage soared (purple line). The 2010 (self-selecting, online) Global Drug Survey found that 51% of regular clubbers had used mephedrone that year, and official figures from the 2010/11 British Crime Survey estimate that around 4.4% 16 to 24 year olds had tried it in the past year.

Similarly, law changes and clampdowns in India resulted in a UK ketamine drought, leading to dabblers (both knowingly and unknowingly) taking things like (the once legal, now Class B) methoxetamine. And indeed, the majority of legal highs on offer are 'synthetic cannabinoids' which claim to mimic the effect of cannabis. In all, it's fairly safe to claim that were recreational drugs like ecstasy, cannabis and cocaine not so stringently prohibited, these 'legal highs' (about which we know very little) probably wouldn't be knocking about.

Still, governments tend to be of the view that any use of drugs is simply objectively bad, so the above is rather a moot point. But what anxious states can do, of course, is ban new legal highs as they crop up. However, even this apparently obvious solution has a few problems— the first being that there seems to be a near-limitless supply of cheap, experimental compounds to bring to market. When mephedrone was made a Class B controlled substance in 2010, alternative legal highs such NRG-1 and 'Benzo Fury' started to appear. In fact, over 550 NPS have been controlled since 2009. Generally less is known about each concoction than the last, presenting potentially far greater health risks to users.

At the same time, restricting a drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 requires evidence of the harm they cause (not that harm levels always bear much relation to a drug's legality), demanding actual research as opposed to sensationalist headlines. Even though temporary class drug orders were introduced in 2011 to speed up the process, a full-out ban still requires study, time and resources. Many have claimed the battle with the chemists in China is one lawmakers are unlikely to win.

And so with all of this in mind, the Queen's Speech on Wednesday confirmed that Conservatives will take the next rational step in drug enforcement, namely, to simply ban ALL OF THE THINGS.

In order to automatically outlaw anything which can make people's heads go a bit funny, their proposed blanket ban (modelled on a similar Irish policy) will prohibit the trade of 'any substance intended for human consumption that is capable of producing a psychoactive effect', and will carry up to a 7-year prison sentence.

Somewhat ironically for a party so concerned with preserving the UK's legal identity it wants to replace the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights, this represents a break from centuries of British common law, under which we are free to do something unless the law expressly forbids it. This law enshrines the opposite. In fact, so heavy-handed and far-reaching is the definition of what it is prohibited to supply that special exemptions have to be granted for those everyday psychoactive drugs like caffeine, alcohol and tobacco. Whilst on first glance the ban might sound like sensible-enough tinkering at the edges of our already nonsensical drug policy, it really is rather sinister, setting a worrying precedent for the state to bestow upon citizens permission to behave in certain ways.

This law will probably (at least initially) wipe out the high street 'head shops' which the Daily Mail and Centre for Social Justice are so concerned about. However, banning something has never yet simply made a drug disappear. An expert panel commissioned by the government to investigate legal highs acknowledged that a 50% increase in seizures of Class B drugs between 2011/12 and 2013/14 was driven by the continued sale of mephedrone and other once-legal highs like it. Usage has fallen from pre-ban levels, but so has its purity whilst the street price has doubled. Perhaps the most damning evidence, however, comes from the Home Office's own report into different national drug control strategies, which failed to find “any obvious relationship between the toughness of a country’s enforcement against drug possession, and levels of drug use in that country”.

The best that can be hoped for with this ridiculous plan is that with the banning of absolutely everything, dealers stick to pushing the tried and tested (and what seems to be safer) stuff. Sadly, this doesn't seem to be the case - mephedrone and and other legal and once-legal highs have been turning up in batches of drugs like MDMA and cocaine as adulterants, and even being passed off as the real things. Funnily enough, the best chance of new psychoactive substances disappearing from use comes from a resurgence of super-strong ecstasy, thanks to the discovery of a way to make MDMA using less heavily-controlled ingredients.

The ASI has pointed out so. many. times. that the best way to reduce the harms associated with drug use is to decriminalise, license and tax recreational drugs. Sadly, it doesn't look like the Conservatives will see sense in the course of this parliament. However, at least the mischievous can entertain themselves with the prospect that home-grown opiates could soon be on the horizon thanks to genetically modified wheat. And what a moral panic-cum-legislative nightmare that will be...

We're not going to believe this report, sorry, we're not

We have the latest salvo in the barrage about how bad foods, those ones that we enjoy, must be taxed and those good foods, the ones we don't so much, must be subsidised. That is, tax sugar and carbohydrates, subsidise fruit and veg. The argument today being that the bad foods have fallen relative in price to the good ones sand that this is very bad, not good.

The report’s authors found that fruit and vegetables had risen in price by up to 91 per cent in real terms between 1990 and 2012, a bigger increase than for other any other food group. “In high income countries over the last 30 years it seems that the cost of healthy items in the diet has risen more than that of less healthy options, thereby encouraging diets that lead to excess weight,” said Steve Wiggins, one of the authors of the report.

The report itself is here.

There's a few things being missed. Weight is a function of calories in, calories expended. We don't gain weight simply because we eat cheaper calories. So this cannot be an explanation for rising obesity levels. Further, all food has become cheaper relative to incomes, so if price really is determining what we eat then we might expect the diet to have become healthier. Whatever budget constraints we had on eating that "good" food have still been relaxed, whatever has happened to relative prices.

But perhaps more importantly than this we're not sure that we believe the price indices themselves. They appear to be looking at the prices that people actually pay for the goods, not at prices for a constant form or type or quantity. Thus it's "prices of fruit" or "prices of vegetables" as they appear in the average consumer basket. And there's a few changes in the composition of that consumer basket over those 30 years.

1) Around the year availability of alomst all fruits and vegetables. This is going to make the average price rather more than what it was when we relied upon the local and seasonal gluts. We also get very much more choice of very much more exotic fruits and vegetables and these are, not surprisingly, more expensive as well.

2) The rise of prepared foods. 30 years ago you could not wander into a supermarket and purchase a prepared salad, not a punnet of sliced fruit etc. Now one can and many do. This is obviously more expensive per unit of salad or fruit but we all seem happy enough to pay it.

3) The rise of organic and fair trade. These are both, by design, premium products at premium prices. And while they're not a vast portion of the food market they are significant enough to influence a price index composed in the manner this report seems to.

So, the price index seems to be composed not of what we actually want to know (are apples more expensive than they used to be?) but of what we actually buy (are we buying more expensive foods, of greater variety and exotica, all year rather than seasonally, in a more prepared state?). So we're afraid that we don't actually believe the stated statistic, whatever problems we've got with the theory that they're trying to push.