Now that we've extended marriage to all let's not make it compulsory

Recent years have seen significant changes in marriage: it's now essentially available to all potential pair couplings of whatever gender definition one wants to use. That doesn't therefore mean that it should become compulsory though. And yet that is roughly what is being proposed:

In 2007, the Law Commission recommended reforming the laws that apply to cohabitants if they separate but no legislation followed. There are nearly 6 million unmarried people living together, many under the illusion that they have the same rights as married couples if they separate.

Resolution is calling for a legal framework of rights and responsibilities for unmarried, cohabiting couples to provide some legal protection and secure fairer outcomes at the time of a couple’s separation or on the death of one partner.

To which our answer is no. For we are believers in choice.

Believers in choice over who you might mingle genitalia with, as we always have been. And also choice over who you might share accommodation with. And even choice as to the economic arrangements that you might want to make surrounding who you mingle or share with. That choice is there in the law as it stands. One is entirely at liberty to live with someone without making formal economic arrangements. One is also able to take up that contract of marriage, something well defined in law. This current suggestion is that that first choice should no longer be available. And as a reduction in choice we're therefore against it.

There is the point of any children that might come from a relationship but their rights and the responsibilities of the parents are already well defined in law.

Essentially the proposal is to introduce common law marriage as a legal position. And English law (except in very odd circumstances involving being in foreign) simply has never recognised it. For the plain and simple reason that if yout want the protections of the contract of marriage then go and get married. Now that all can do so it really isn't the time to make it compulsory.

Hard-headed misunderstandings

Today I was on BBC World talking about obesity. My opposite number Tam Fry pointed out that the obese cost the rest of us while they are alive through their use of the NHS and other state services. I pointed out that they don't totalled up over the lifetime because the obese die earlier and take much less out in pensions and end-of-life care.

In saying this I was trying to make the point that this doesn't mean we shouldn't care about obesity, or that it's (heaven forbid!) a good thing because they cost the rest of us less. Are people so obsessed with the government's balance sheet that pointing out the obese cost the government less by dying earlier seems equivalent to saying I want them to die earlier?

My point was that most of the costs of obesity are to the individual, not to society. There is no harm principle argument here that we should intervene into their lives because they are hurting others. The case for intervening into the lives of the obese would be to make them better off, because say, obesity shortens their lives, makes them more likely to get diabetes, or makes them less happy.

Now I don't think there's never a case for paternalistic intervention (we can all think of crazy thought experiments) but I do think we should be very careful before we decide we can run someone's life for them. That's because usually the government gets things wrong when it tries to plan on other people's behalves.

Most people would not like to live in a society where people are not at least in some cases free to take the steps that lead to obesity—even if overall they'd prefer there were fewer obese people. Most people would find it rather chilling to have a society where the diets and exercise regimes of the obese were centrally managed and rigidly enforced.

By contrast, the Mexican 'squats for bus tickets' scheme, though very likely to be ineffectual, is probably not such a bad idea.

Make Britain safer: bring back pistols

We live in peaceful times – at least compared to the past thousand-ish years. Crime, especially personal violence, has been reduced significantly since the 13th century (though not always continuously). The drop looks something like this:

What explains the drastic decline in violent crime, specifically between 1500 and 1900? Why has crime spiked up (moderately) from 1900 – 2010? The widely preferred explanation for the fall in crime – particularly homicide – is referred to as the “civilizing process”, which claims that criminal breaking points can be attributed to the growth of centralised power (i.e. state power), which created more structure and stability in regional areas.

The conventional wisdom…attributes the decline in personal violence to the “civilizing process” first suggested by Elias (1939) who hypothesized that the primary cause was the transformation of Europe from a large number of fiefdoms in the Middle Ages to a small number of large, centralized nation states under a single monarch. The centralised state instituted and enforced a monopoly on violence, known as the king’s peace.

To this day, the ‘civilizing process’ remains the longest-running, widely accepted theory and continues to shape crime and policing policy. But, despite its acceptance, there are some very notable flaws in the theory, including the fact that much of the evidence shapes up to disprove the thesis:

Belgium and the Netherlands were at the forefront of the decline, yet they lacked strong centralized governments. When Sweden joined the trend, it wasn’t on the heels of an expansion in state power either. Conversely, the Italian states were in the rearguard of the decline in violence, yet their governments wielded an enormous bureaucracy and police force...

...the civilizing process theory is not consistent with the rise in violence between 1200 and 1500, it does not explain the sudden and precipitous decline and reversal of trend that occurred in the 16th and 17th centuries, and it is not consistent with the 1793 reversal of trend.

A new paper from Carlisle E. Moody published last month provides an alternative theory last century’s decline in violence. The paper, “Firearms and the Decline of Violence in Europe: 1200-2010”, finds that the sudden historical drops in crime are consistent with the “invention and proliferation of compact, concealable, ready-to-use firearms” which “caused potential assailants to recalculate the probability of a successful assault and seek alternatives to violence.”

And unlike the civilizing process theory, Moody's firearms theory remains consistent with the evidence and breaks in violence. As concealed weapons became more available historically, crime rate dropped radically. (Bolded mine.)

Homicide was increasing before the invention of concealable firearms and decreasing after. While there may be many other theories, the sudden and spectacular decline in violence around 1505 and again around 1610-1621 is consistent with the theory that the invention and proliferation of concealable firearms was responsible, at least in part, for the decline in homicide. The landscape of personal violence was suddenly and permanently altered by the introduction of a new technology. The handgun was the ultimate equalizer. The physically strong could no longer feel confident of domination over the weak.

Some of these arguments may sound familiar; they're the ones those crazies over the States tend to go on about - guns 'equalize' the playing field regardless of physical strength and 'psyche out' violent perpetrators who might be more willing to attack their victims if they knew they were unarmed.

But according to the report, those crazies have some strong points. The report cites several studies which found that the possibility that a victim might be armed deters criminals from acting:

Even in the United States today, criminals are reluctant to encounter armed victims. In 1981 Wright and Rossi interviewed 1874 incarcerated felons in ten states. Eighty-one percent agreed with the statement, “A smart criminal always tries to find out if his potential victim is armed.” Thirty-four percent report being, “scared off, shot at, wounded or captured by an armed victim. (Wright and Rossi 1986, pp. 132-155) Using the same data, Kleck found that, among criminals who had committed violent crimes or burglaries, 42 percent had been deterred during an attack by an armed victim and 56 percent agreed that, “most criminals are more worried about meeting an armed victim than they are about running into the police.”(Kleck 1997, p. 180)

Perhaps, then, we might admit (based on evidence, consistency and lack of other credible theories) that firearms reduced violence historically; but in the modern era, guns cause more violence than they deter. But that's not the case either:

The government in England has been placing increasingly stringent controls on guns especially handguns, since 1920, reducing both the actual and the effective supply of firearms. (Malcolm 2002) The homicide rate in England in 1920 was 0.84 and the assault rate was 2.39. In 1999, the corresponding rates were 1.44 and 419.29. Thus both the homicide and assault rates increased as the effective supply of handguns declined.

That's a 17,544% increase in England's assault crime over the past 100 years. In truth, there is no explicit correlation between gun control laws and murder rates between countries (Switzerland and Israel “have rates of homicide that are low despite rates of home firearm ownership that are at least as high as those in the United States.”) It is the case that handguns used in crimes in the UK have doubled since they were banned in 1997. Guns can't account fully for the drop in crime throughout the 20th century, nor can they account fully for the rise in violent crime over the past 100 years, but there is no doubt that accessibility to firearms has worked as a successful deterrence against criminals in progressive societies and that bans have ensured that any handguns in England are only falling into criminal hands.

Should we proliferate handguns around England tomorrow? Probably not. (Obviously we should begin with firearm training sessions - safety first!) But liberalizing gun laws should not be off the table. Historically, they've earned it.

Watch Mark Bittman destroy his own argument

This is really most amusing from Mark Bittman over in the New York Times. For those who haven't heard of him he's supposed, really, to be a food writer. But every column seems to come out as a call for a revolution in society. Larded, of course, with references as to how this will make food better so as to justify his niche and position. But his latest column really rather manages to trip over itself:

The world of food and agriculture symbolizes most of what’s gone wrong in the United States. But because food is plentiful for most people, and the damage that conventional agriculture does isn’t readily evident to everyone, it’s important that we look deeper, beyond food, to the structure that underlies most decisions: the political economy.Progressives are not thinking broadly or creatively enough. By failing to pressure Democrats to take strong stands on everything from environmental protection to gun control to income inequality, progressives allow the party to use populist rhetoric while making America safer for business than it is for Americans.

You see what we mean, it's a bit of a leap from conventional agriculture to gun control really. And he ends with that call to revolution:

It’s been adequately demonstrated that more than minor tweaks are needed to improve life for most people. Let’s try to make sense of where the world is now instead of relying on outdated doctrines like “capitalism” and “socialism” created by people who had no idea what the 21st century would look like. Let’s ambitiously and publicly philosophize — as the conservatives do — and think about what shape a sensible political economy might take.

The big ideas and strategies for how we should manage society and thrive with the planet are not a set of rules handed down from on high. To develop them for now and the future is a major challenge, and we — progressives and our allies — have to work harder at it. No one is going to figure it out for us.

Well, there's a certain problem with those big ideas and strategies really. A problem that he himself mentions earlier:

We don’t all agree on goals, and we don’t agree on whether things are working or in need of repair.

So, if we don't agree on the goals then how can we have big ideas and strategies to get to wherever it is that we disagree about? The column's headline is:

What Is the Purpose of Society?

And that's where we really, really disagree. We don't believe that there can possibly be a goal for society. Not one that we all agree upon and then have big ideas and strategies to reach.

Except, of course, that the goal of society is for us all to be able to do whatever it is that we wish to so long as in our doing so we don't damage others' opportunities to do the same. And we're deeply unconvinced that this goal is going to be reached by anyone having big ideas and strategies: unless it's the one where we tell the people with the big ideas and the strategies to get out of our lives and go and do something more interesting with their own.

The most frustrating Vox article ever

The internet has made everybody audible. And, as a result, anybody can become a victim of a pitchfork-wielding mob, if you happen to say something online that the mob wants silenced. Nowhere has this reality been clearer than in the backlash against nascent feminism on Twitter.

This is the opening premise of a new Vox article on the Men’s Rights Movement (MRM), which is the most quotable thing I’ve ever read. (That is not necessarily a compliment.)

The author, Emmett Rensin, ventures into Chicago suburbia to talk to ‘Max’ - a young mid-20's man who views himself as a Men’s Rights Activist. We are taken into his world and explore his views on feminism, religion, and the world as he perceives it. I found the whole experience very painful, for two reasons:

First, I am no defender of the “Men’s Rights Activists” (MRA), who often take serious issues - such as paternal rights and domestic violence against men - and use them as a jumping-off point to threaten women online or to justify sites like this as good for the movement.

Max is no villain, but rather an immature guy who is defined more by his struggle to discover his beliefs than by any particular belief he holds at the time: Max is an MRA, but kinda not (he prefers to think of himself as a ‘humanist’). Max agrees with the MRM philosophy, but not with the radicals. Max tweets mean things at feminists, but does not condone threats or violence. Max is wishy-washy and says silly things a lot. Max isn't likeable. He's a one-note caricature. And it's a long article...

The other problem with the article comes down to the author's narration; his narrow view of gender issues makes the article painfully ironic. Rensin gives the allusion of trying to get to the heart of what motivates men like Max to engage with the MRM, but quite obviously wants to make sure we hate Max. After all, Max lives in a ethnically homogenous area:

When I met him, Max lived in the River North neighbourhood of Chicago. River North is — at 70 percent white in a city where the white population is 32 percent and declining — one of the few places one can live in the Chicago where it is still possible to avoid even a vague awareness of the city's racial and cultural dynamics.

And he is privileged:

Max is remarkably unassuming in appearance, handsome enough and normally tall; equally imaginable in board shorts and a snapback as he is in the sort of graduation suit one wears to a first post-collegiate interview downtown.

And he is disconnected from reality:

For all his derision toward the "professional victimhood" of feminists, there's something a little less than sarcastic in Max's own sense of oppression. Hard-pressed as the social justice left is to admit any advantage, the West these last decades has seen the rhetorical value of victimized stance. The irresistible cudgel of "I am oppressed and this is my experience and you cannot speak to it because you do not know" is valid enough, of course, especially in those cases where ordinary enculturation does not provide natural empathy toward some suspect class. But it is a seductive cudgel, too, especially alluring when it can be claimed without any of the lived experience that makes marginalization a lonely-making sort of suffering. American Christians are "persecuted" now; men are the ones being "squelched" by feminism; white Americans are the victims of "reverse racism." The "victim card" is a child of the ‘70s, and 40 years out who wouldn't use it, no matter how disconnected from reality?

It’s this last paragraph that really gets me - "professional victimhood". A spot-on observation from Rensin, that stops short one step too soon.

It is indeed ridiculous to push the idea that men are oppressed in western society. While grievances over the role of the father, forced-masculinity and male-targeted abuse are all important and legitimate discussion points, they are part of a much wider discussion about how gender roles are dictated in society and don't add up to conclude that men's rights are the most vulnerable and abused rights in 2015.

But are women oppressed? Just as the author questions whether men are really being "squelched" by feminists or whether American Christians are really being "persecuted" by atheists or non-believers, isn't it also time to ask whether women should still be able to claim professional victimhood in the western world?

I'd say they can, when it comes to violence - particularly domestic abuse and rape. But that isn't what 'professional feminists' are talking about. They seem much more concerned with the gender pay gap (which doesn't actually exist for young women working in the UK) and iconic t-shirts (which are...iconic) than they are with issues that actually harm and oppress women. Too often, feminists are relying on victimhood to promote their policies, making little-to-no effort to address the real, forced victimhood created through violence.

It's hard to embrace modern feminism when it's leaders are defining it as pro-victimisation. Many men and women want nothing to do with that.

As our least-favourite caricature notes:

My mom says she's a feminist. And I guess in the way my mom means it, I still am. But she doesn't know how it is now. For her, feminism means ‘everybody is equal', but if you said that now, these social justice warriors on Tumblr would call you a sexist and garbage and tell you to die. But I didn't realize that at first. I thought feminist meant ‘women should be able to vote and have jobs', which I'm obviously cool with.

I'm cool with that too, Max. I'm cool with that too.

The real problem of three-parent families

In a world first, MPs recently voted to permit IVF babies created using biological material from three different people, in order to prevent serious genetic diseases caused by faulty mitochondria passed on by the mother. This looks set to benefit around 2,500 UK families. Much has been made of the creation of ‘three parent babies’. That term is misleading; whilst the biological material of three people is involved, less than 0.02% of the child’s DNA will come from the anonymous female mitochondrial donor. However, there is another form of ‘three parent’ baby-making, the rules for which are long overdue reform: surrogacy.

The use of surrogacy is on the rise, no doubt in part fuelled by same-sex partnerships. However, the process is fraught with difficulties, from the assignment of parental rights to the non-enforceability of surrogacy agreements, and, crucially, the fact that ‘commercial’ surrogacy is illegal in the UK.

First of all, the parental rights assigned at a surrogate child’s birth fail to reflect who will actually care for the child. Under UK law, the carrier of the child is considered the legal mother, no matter if they are genetically related or not. If the carrier is married or in a civil partnership, her partner becomes the child’s second parent. A genetically-related commissioning father will be considered the second parent if the surrogate doesn’t have a partner, but a commissioning mother will never automatically receive parenting rights to the child.

To obtain proper legal parenthood, commissioning parents must apply for a Parental Order no more than six months after the birth of their child. Only couples may apply for an order and they can take months to process, leaving a child’s main carers in legal limbo.

Another interconnected and significant issue is that surrogacy agreements are only considered informal arrangements, and cannot be legally enforced. This means that no matter how careful or extensive arrangements are made, there is no guarantee that they will be honoured. In the UK where the surrogate is considered the legal mother, they are able to refuse to hand over the child, even if it is genetically unrelated to them.

Surrogacy agreements with legal weight would alleviate both these problems. An obvious solution would be the recognition of some kind of ‘surrogacy pre-nup’, outlining what compensation or fees will be given to the surrogate, as well as establishing the ‘correct’ parental rights from the moment of birth.

However, another significant barrier to the use of surrogacy is the fact that commercial surrogacy is strictly prohibited in the UK (as it is in a large number of other countries). Currently surrogacy can only take place on ‘purely altruistic’ grounds, with compensation limited to ‘reasonable expense’ only. Prospective parents are banned from advertising their interest in surrogacy, as are potential surrogates. If no suitable surrogates can be found in the UK, commissioning parents often look to certain US states (such as California) or the 'baby factories' of India, Thailand and Ukraine to find a willing surrogate.

The foundations of the legal status of surrogacy stem from The Warnock Report into IVF in 1984, which stated “it is inconsistent with human dignity that a woman should use her uterus for financial profit”. But what exactly is so demeaning about offering gestational services for financial compensation or gain?

It’s often argued that commercial surrogacy substitutes the norms of parental love with market norms. It encourages us to think of parental rights as more like property rights than a fiduciary relationship, and the ‘selling' of children, especially for profit, is wrong. However, what’s taking place with commercial surrogacy is the purchase of gestational services and the delivery of a child, not the child itself. The property rights involved are those of the surrogate's, who has rights of control and exclusion over her body and (most liberals will argue) may use her uterus as she sees fit.

Another related idea is that there are some things - like votes- which are simply too fundamental and valuable to sell, and that the bringing about of a child is one of these things. This type of argument is made by Michael Sandel, who claims that putting a price on some of the ‘good things’ in life corrupts them, and that their commodification results in their degradation.

However, paying for gestation does not diminish the innumerable other ways in which it has value. Placing a market value on something is not to say that it has no value over and above its price - ‘priceless’ paintings are still bought and sold for sums of money. The gift of a child to a couple, and the gratitude felt towards a surrogate can indeed be priceless, even if money is exchanged.

The real question is what informed and consenting adults may do with their bodies and its functions. Arguments defending prostitution form an obvious parallel here. But even prostitution aside, there are a number of ways we profit from using our bodies and its products. We allow hair, blood, and tissue to be sold, so why not the uterus? People use their hands and brains for profit, and ‘sell’ their bodies to medical science and to sporting contracts — what then, is so immoral about gestating someone’s child for a fee? Sperm donation is not particularly morally troubling to us, even though this too separates the genetic and biological elements of baby-making, allows the donor to give up parental rights, and to profit from their act.

Admittedly, many may feel uneasy about the entire surrogacy process; it uses our bodies in ways which are somewhat unnatural, and uproots our usual intuitions about motherhood, pregnancy and prenatal bonding. Whilst we may accept it in extreme, altruistic cases, perhaps 'normalizing' the process with a commercial market leaves an unpleasant taste in our collective mouths. However, a feeling of unease shouldn’t be justification alone for prohibition.

Our comfort zones and thoughts on what are acceptable change over time. Single parenting loses its stigma, and the acceptability of same sex couples grows. When first introduced the contraceptive pill was considered an aberration of nature. Today it is considered one of the biggest feminist breakthroughs of the 20th century. Perhaps with time the position of ‘the gestator’ will come to be viewed as a honourable and respectable profession, bringing joy to families and worthy of commercial recognition. Science lets us wage war on biological conventions and constraints, and it is time for us to tackle the social and legal barriers, too.

Anti-slavery laws don't help many sex workers, and may end up harming them

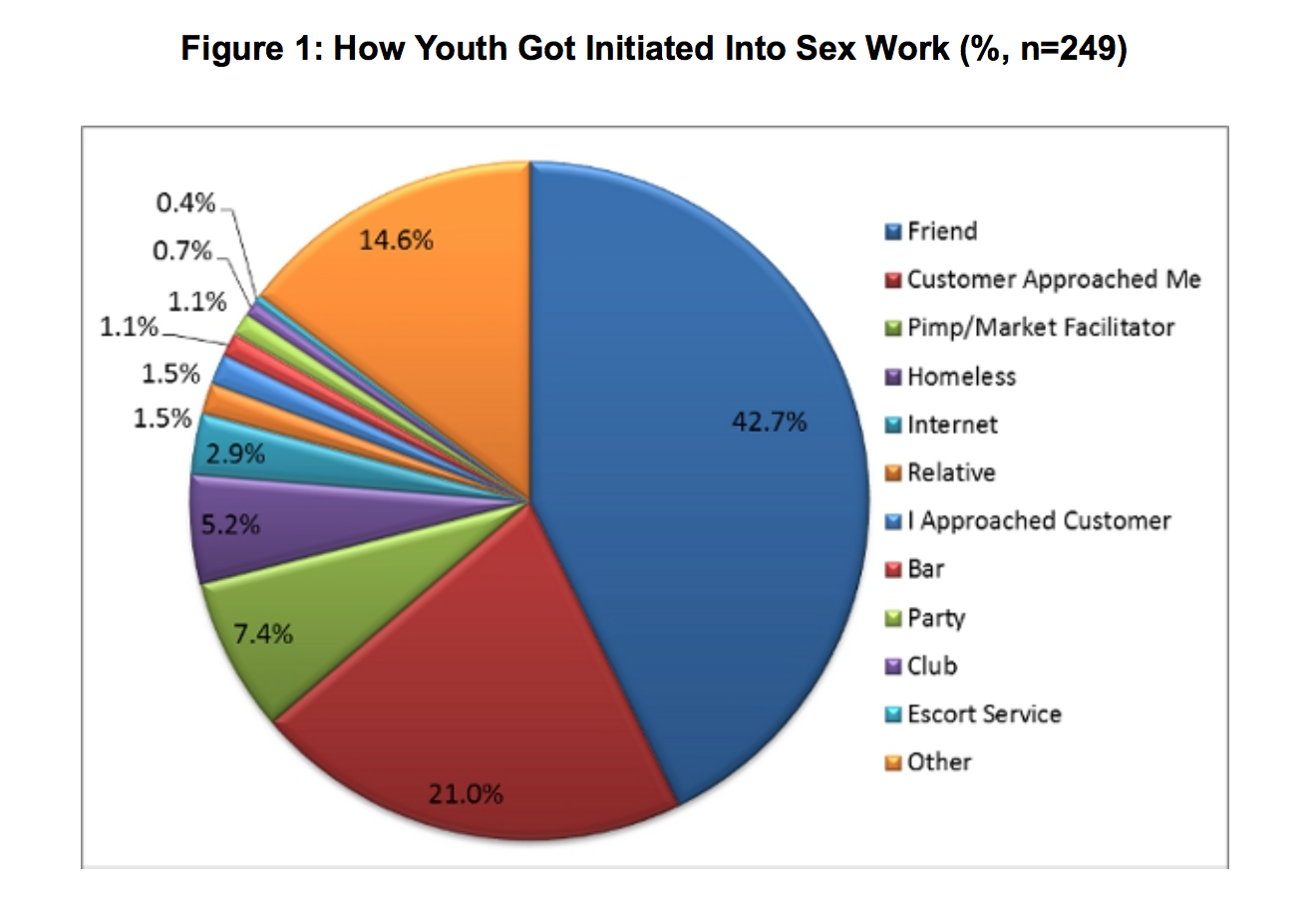

Some people blame sex slavery, or trafficking, driven by pimps for keeping young girls in prostitution. Young girls are drawn in and brutalised by pimps, the conventional wisdom goes, and tackling this is the best way to reduce the number of girls trapped in prostitution. The Modern Slavery Bill in the UK is motivated by this kind of assumption. A new study of underaged sex workers in New York City and Atlantic City seems to suggest that this is actually very rare. Using the largest data set ever gathered in this kind of work in the US, researchers surveyed pimps and sex workers to find out how common pimping was. Figures 1 and 2 below show how few underaged girls are introduced to sex work by pimps and how few actually have pimps on an ongoing basis:

In fact, poverty and lack of access to work, housing or education seem to be what keep girls in prostitution:

None of this tells us that anti-slavery legislation is bad, but it does seem to miss the point somewhat. However, one fact cited by the authors does mean we should think twice about anti-slavery laws: only 2 percent of underaged sex workers said that they would go to a 'service organisation' if they were in trouble, because 'the anti-trafficking discourses and practices they would encounter in these organizations threaten to criminalize their adult support networks, imprison friends and loved ones, prevent them from earning a living, and return them to the dependencies of childhood.'

If only a small number of sex workers count as being trafficked, and anti-trafficking laws alienate others from the services set up to protect them, then anti-slavery legislation may end up having very perverse consequences indeed.

Tough on the causes of crime

Let's be very reductionist and say that the prevalence of crime is affected by people's biology, their upbringings, social environment and finally the crime and punishment system. In many ways the hardest things to change are their biology, so let's just ignore these for the time being (although see 1 2). Then what we have are upbringings/society and the crime and punishment system. Being very broad brushed we could say that before 1800 people put little faith in the former and lots in the latter. Nowadays people tend to be split between whether they place their faith in being tough on crime or tough on the causes of crime (can't resist dropping this link here).

I favour both approaches, but outside of the fact that being just selected into a better school makes you a bit less likely to commit crimes, most social interventions we know don't seem to have much effect. It might be a dead end. Start with the fact that 65% of UK boys with a father in prison will go on to offend. That's easy to understand on the social-upbringing account: these people probably lack nurturing environments, live in bad neighbourhoods and so on.

The problem is that these just-so explanations don't seem to fit the data.

- Parenting: here's a 2015 US paper showing "very little evidence of parental socialization effects on criminal behavior before controlling for genetic confounding and no evidence of parental socialization effects on criminal involvement after controlling for genetic confounding".

- Family income: here's a 2014 Swedish paper showing "here were no associations between childhood family income and subsequent violent criminality and substance misuse once we had adjusted for unobserved familial risk factors".

- Bad neighbourhood: here's a 2013 Swedish paper finding "the adverse effect of neighbourhood deprivation on adolescent violent criminality and substance misuse in Sweden was not consistent with a causal inference. Instead, our findings highlight the need to control for familial confounding in multilevel studies of criminality and substance misuse". (In fact, this weird 2015 US paper found that low-income boys surrounded by affluent neighbours committed more crimes).

I realise there are other studies saying different things—I don't want to sci-jack or be the Man of One Study—but many of these use caveman methodologies that don't even attempt to account for the potential that some people are born different to others (e.g. some have more testosterone). And I think we can be cautiously confident in these findings because they fit with other things we know.

So we're left with enforcement. Can that make a difference? Today black Americans commit many more crimes per capita than whites, despite committing fewer than them in the late 19th Century. It's possible that the results above are only true for a narrow range of environments, and thus that social-familial affects are driving this.

But in any case do we really think that blacks in today's USA live in worse environments than the blacks of the post-bellum USA? If environments are improving and people are pretty much the same genetically, then the criminal justice system may be the big changing factor.

I think the criminal justice system looks like the area where research could most plausibly lead to improved outcomes. Consider the imposition and enforcement of restrictive drug laws, which coincided with the crime wave, and which may increase violent crime (e.g. by inducting people into the criminal life, or by providing a lucrative trade to fight over).

Some way of changing improper or inadequate enforcement—e.g. liberalising drug laws—may be a can opener to assume but it's nothing like the assuming the can opener of changing genetics or magic social interventions that actually work.

Of all the idiot suggestions

Of the idiot policies that politicians have tried to bake over the years this one rather takes the cake:

Scottish Labour MP Thomas Docherty is calling for a national debate on whether the sale of Adolf Hitler’s “repulsive” manifesto Mein Kampf should be prohibited in the UK.Docherty has written to culture secretary Sajid Javid about the text, pointing out that it is currently “rated as an Amazon bestseller” and asking the cabinet member to consider leading a debate on the issue. An edition of Mein Kampf is currently in fifth place on Amazon’s “history of Germany” chart, in fourth place in its “history references” chart, and in 665th place overall.

“Of course Amazon – and indeed any other bookseller – is doing nothing wrong in selling the book. However, I think that there is a compelling case for a national debate on whether there should be limits on the freedom of expression,” writes Docherty to Javid.

Excellent, let us have that debate.

The answer is no.

On the simple grounds that freedom of speech really does mean what it says. People, even dead people, are free to spout their opinions however absurd, racist, hateful, jejeune or potentially damaging they may be. They may not libel and they may not incite to violence but within those constraints freedom really does mean freedom.

“This is not a debate around political books or manifestos or books which cause offence … What Mein Kampf and books like it do is specifically set out to incite hatred. It is literally the manifesto for Nazism.”

And that is why this is so important for this specific book. Yes, Hitler really did write down what he was going to do and when he gained power he went and did it. Which is why this specific book must remain available. So that we all remember that people often do have their little plans and it's wise to make sure that certain people don't get to enact them. As with that other little book that contributed so much to the tragedies of the 20 th century. Sometimes those who talk about the elimination of the bourgeoisie as a class really do mean it. Better to be warned and avoid, no?

Restating the case for freedom of speech

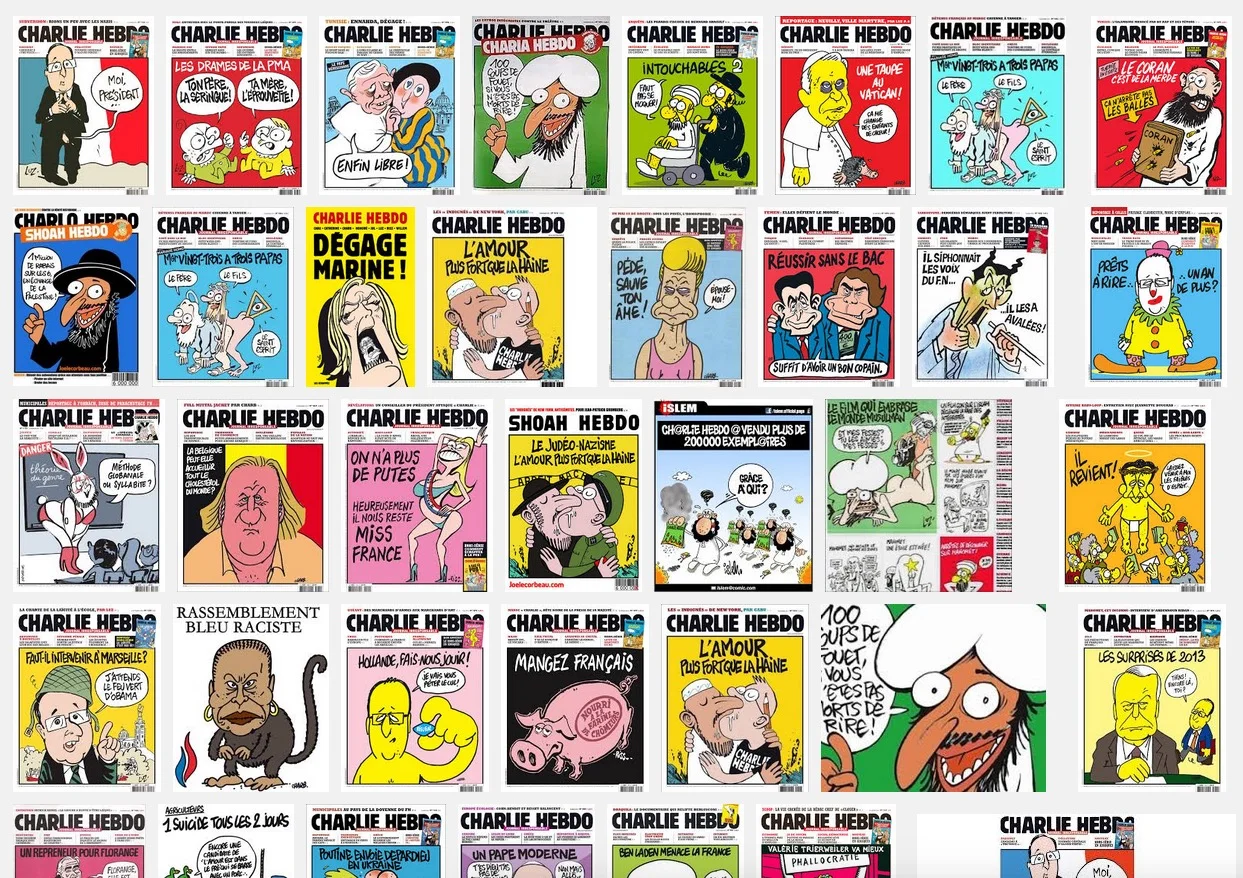

One thing that’s becoming clear in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo tragedy is that when it comes to mockery, a lot of politicians and spokespeople have the backbone of a paramecium. All these people trying to defend us against the insensitivity of mockery have missed something vitally important: Not only is there usually nothing wrong with mockery, there is, in actual fact, often something very good about it – because mockery is frequently a powerful tool for highlighting the absurd and the inane. In such instances the reason mockery usually cuts so deep to offend is that it is exposing some absurdity or inanity in the belief held. To silence mockery is to be in danger of suppressing the wit that exposes the kind of beliefs that can only be held by surrendering the mind to reject evidence and rational enquiry. If we rightly endorse free speech as one of the great human necessities, we should insist the same kind of endorsement for mockery too. Free speech is one of those issues about which it is difficult to say anything original. It has been written about so well by people like John Milton, Voltaire, John Stuart Mill, Thomas Paine and George Orwell. John Milton's Areopagitica is perhaps the best of all works on this - being acutely perceptive not just about free speech but about the need for a free press too.

Alas, even though these great men make it difficult to say anything original on free speech, if what they've said has been forgotten by modern politicians to the extent that the qualities they propounded are gradually being eroded away by our ever-increasing nanny state authorities, there will always be the need for a reminder.

The general wisdom that has been distilled from these great writers on our liberty of free expression is that we will not agree with every opinion being proffered, but we should defend everyone's freedom to proffer those opinions. We should do this not just to protect the right of the person with the opinion, but also to protect our right to hear opinions too. In other words, in denying someone the right to voice an opinion, we at the same time deny ourselves access to that opinion, so we decline the opportunity to hear something that may differ from the consensus or challenge widely held viewpoints.

We may not agree with everything we hear, and some of the things we hear may be vile, controversial or damn stupid, but we do ourselves an injustice if we fail to hear the dissenting voices, because even the most discordant and discrepant opinions may contain within them at least a grain of truth. Therefore we should be impelled to consider them carefully, for in doing so we force ourselves to question how we know what we do and whether the sources from whence our knowledge came were reliable and verifiable.

When it comes to free speech and mockery, then, so long as no threat is being made, or slanderous or libellous lie about a person being told, or employer/employer protocols breached, it is in our best interests to have complete freedom to say/write/draw whatever we wish, however controversial or repugnant.

Sadly, it becomes ever more apparent nowadays that these important principles regarding free speech are being gradually forgotten, or in some cases deliberately eroded away, by the kind of charmless busybodies who would call for the arrest of a Tweeter or the sacking of an MP or journalist or the condemnation of a satirist who says, writes or draws something they don't like. As is evident to anyone with even the sketchiest understanding of human nature and basic philosophical familiarity, the more censorious we become the more we become prisoners of our interference.