George just doesn't quite get it, does he?

A quite wonderful rant from George Monbiot. Apparently all those firms that pay their employees lots of money are in fact just vampires sucking the lifeblood and all that is good and holy out of said employees:

To seek enlightenment, intellectual or spiritual; to do good; to love and be loved; to create and to teach: these are the highest purposes of humankind. If there is meaning in life, it lies here.

Those who graduate from the leading universities have more opportunity than most to find such purpose. So why do so many end up in pointless and destructive jobs? Finance, management consultancy, advertising, public relations, lobbying: these and other useless occupations consume thousands of the brightest students. To take such jobs at graduation, as many will in the next few weeks, is to amputate life close to its base.

I watched it happen to my peers. People who had spent the preceding years laying out exultant visions of a better world, of the grand creative projects they planned, of adventure and discovery, were suddenly sucked into the mouths of corporations dangling money like angler fish.

It is just ever so slightly odd to hear a man reputedly of the left complaining that the workers are receiving too much money. We did rather think that was the point of said left, to ensure that the workers by hand and brain received their just allocation of the moolah.

Other than that it's the arrogance on display here from Monbiot that is so breathtaking. It may be that he thinks that the meaning of a good life is to teach, to create. But that's his view of life, one he's entirely welcome to of course, but he's not welcome to impose it on others. Others can, and do, have entirely different conceptions of what that good life is. Perhaps to be able to raise and take care of a family: something that a decent income does make rather easier. Heck, some people even enjoy being bankers.

Or to be more serious about it, what on earth is anyone doing calling finance "useless"? Or indeed lobbying? Finance is the mobilisation of the savings of this generation into the building blocks of the better world of tomorrow. This is useless? Or badgering a minister into dropping one or other of their foolish and ill thought out plans as a lobbyist does not add value to all our lives?

So it's not just that he's wrong in trying to impose his own view of life upon others, it's that he's not even got a reasonable view of what those others are in fact doing.

So, situation normal on the Guardian comment pages then.

The FCA meddles with investment banks

In June 2014, the Chancellor created a Fair and Effective Markets Review (FEMR) of financial services, co-chaired by the Bank of England, FCA and HM Treasury. The report is due next month but has been widely trailed. Before we see that review, and in an effort to keep itself busy, the FCA has announced a further review covering some of the same ground, the Investment and Corporate Banking Market Study (ICBMS): “We are examining issues around choice of banks and advisers for clients, transparency of the services provided by banks, and bundling and cross-subsidisation of services.” Each of these reviews takes a year and costs you and me hundreds of millions of pounds. The FCA spends around £480m, growing at 6% p.a., and this is their biggest single project. It must cost the industry a similar amount in dealing with the FCA’s 3,000 staff. We consumers pick up the costs: every bill from my stockbroker has a £20 “Compliance charge.” That is hardly a key issue for most electors as they vote on the government every five years, so this unrestrained incubus feeds itself.

This second review is not just duplication: neither should be necessary at all. Both arise from Treasury and FCA failure to understand how markets do and should work – and we now have the Competition and Markets Authority. It was launched only last year and could perfectly well cover financial as well as other services. I would even go so far as to allege that the financial services regulators’ adversarial approach is in part responsible for the scandals. The FSA, and now the FCA, have forced banks to close ranks to deal with what must seem to them a common enemy. As Adam Smith pointed out two and a half centuries ago, putting competitors in the same room is likely to be bad for competition.

The Bank of England, by contrast, used to preside over the sector in the manner of a kindly uncle, nudging potential miscreants away from their misdoing, but not taking on the sector as a whole. Maybe the BoE can recover that role.

The terms of reference of the ICBMS seem to indicate that the FCA suspects clients do not choose their banks and advisers in the way they should, that things are not fully transparent and that cross-subsidy of services is a malpractice.

The first of these is a remarkable suggestion: that the FCA knows how clients should make decisions better than the clients do. Enough said.

On the second, in any market, the products should indeed be fully and accurately described, as the law requires. In the case of manufactured foods, for instance, the labeling requirements are extensive. But the FCA’s brand of “transparency” implies more than just product description: it means revealing everything about the product. If it were applied to oranges, it would require not just the variety, country of origin and the terms of trade proposed, but also the name of the supplier, the date purchased and the price paid by the retailer. Markets do not work this way: competition, along with proper product description, protect buyers by enabling them to compare.

The third implication, that bundling and cross-subsidies are wrong, is the most revealing. When I buy a car, I do not expect to buy all the parts and then have to put them together. I could do that, but bundling the components is far more convenient, and cost efficient, for both parties. And if I make £1 on a dozen oranges but £2 on a dozen pineapples, are my pineapples cross-subsidising the oranges? But then if the oranges sell for 50p each and the pineapples for £2, my margin on oranges is 17% and on pineapples is only 8%. Now the oranges are cross-subsidising the pineapples. Which is the more wicked?

The reality is that every market allows the seller a maximum price whittled down by competition, every seller has different costs, and some things are therefore more profitable than others. The notion of “cross-subsidies” is fantasy.

The FCA’s meddling with financial services adds cost to the sector as a whole, in addition to the growing burden of EU regulation. And it damages competition through a failure to understand how markets work. And its antagonistic approach may even be creating a climate where malpractice is more likely. In short, it is counter-productive.

Ring fencing banks

Apparently “City leaders” are now “in secret talks with Treasury on weakening the ‘ring-fence’ scheme after fears global lenders will abandon Britain” (Sunday Times, 17th May). This has been precipitated by the threatened departure from these shores of HSBC. The only surprising thing about this news is that it has taken so long. My blog on the topic in December 2012 concluded “It is truly astonishing that this [Vickers] Commission should choose to focus its entire attention on the area that matters least [ring-fencing the banks’ retail activities]. The consequence of adopting their suggestions, as Vickers himself seems to be pointing out, can only be that we will hobble our own financial sector at great cost to the economy and the British taxpayer.”

The Treasury has to this day claimed that the public were demanding ring-fencing but that is nonsense. Hardly anyone understands what it involves. Invite the general public to sign a ring-fencing petition and see how many sign up. The only reason they might is because the big banks do not like it. Those few denizens of the City and Westminster who do understand what it involves fall into two camps: fantasists and realists.

The fantasists believe that investment bankers brought down their retail siblings and that, in turn, created the 2008 crash. Actually it was caused by the retail sector giving mortgages, largely under US government instruction, to poor people who could not pay their debts. Much the same happened in the UK: remember those building societies which turned themselves into retail banks? They went to the wall first.

The realists know that however the regulators write the rules, those working for the same global corporation will find ways of cooperating. That is what global corporations do. Chinese walls are not even paper thin.

One, rather more practical, option was completely to separate retail from wholesale as the US used to do. That was abandoned by the Vickers Commission for good reasons.

The new government has better things to do with its time and attention than fiddle around with this, starting with resolving a deal with the EU. There is zero chance that the rest of the EU is going to ring-fence their banks. The Treasury should announce that, to be consistent with other EU banks, the whole topic will be postponed until after the EU referendum.

No, let's not try to abolish cash

There's an idea being floated that we should abolish cash, move over entirely to electronic money, so as to be able to control boom and bust in the economy. There's three reasons (at least) why we think this is a bad idea:

In this futuristic world, all payments are made by contactless card, mobile phone apps or other electronic means, while notes and coins are abolished. Your current account will no longer be held with a bank, but with the government or the central bank. Banks still exist, and still lend money, but they get their funds from the central bank, not from depositors.Having everyone’s account at a single, central institution allows the authorities to either encourage or discourage people to spend. To boost spending, the bank imposes a negative interest rate on the money in everyone’s account – in effect, a tax on saving.

Faced with seeing their money slowly confiscated, people are more likely to spend it on goods and services. When this change in behaviour takes place across the country, the economy gets a significant fillip.

The recipient of cash responds in the same way, and also spends. Money circulates more quickly – or, as economists say, the “velocity of money” increases.

What about the opposite situation – when the economy is overheating? The central bank or government will certainly drop any negative interest on credit balances, but it could go further and impose a tax on transactions.

So whenever you use the money in your account to buy something, you pay a small penalty. That makes people less inclined to spend and more inclined to save, so reducing economic activity.

The first and most obvious failing here is that of privacy, liberty even. Who really wants the government (whether the political one or the State or the central bank) having a record of each and every transaction in the economy? The nothing to hide, nothing to fear line isn't actually true we're sorry, but it isn't. That amount of information: that amount of control even. You can imagine the sort of horrors that would result. Seriously, how long before someone starts demanding that only 3 units of alcohol, 6 grammes of salt, a day and no more than one hamburger a week can be bought with that one, single, electronic account?

The second is that it is getting the point and purpose of the economy the wrong way around. We, us people, the citizenry, we're not here to make the economy hum along. Having an economy that hums along is nice of course but it is to serve us, not the other way around. Thus imposing radical change upon us for the sake of the economy is simply nonsensical. It is to have the logic of the matter completely arse over tip.

And the third is that it almost certainly wouldn't work to control the economy in the manner described. Because the usual cause of booms and busts is the authorities themselves getting those economic levers set to the wrong levels. We might argue this from Hayek's point, that no one can ever know enough to set them to the right positions, we might borrow from Mancur Olson and point out that the State is, in reality (at least the people controlling it are) a stationary bandit. Much more interested in maintaining control through re-election than they are in the long term of the economy. This is why we always have a relaxation of monetary and fiscal conditions in the run up to an election: that's just the way that it works.

In this reading the boom and the bust is caused by political control of those levers of the economy: strengthening that control really isn't going to solve that problem.

As usual around here our objections are a mixture of concerns over liberty, morality and plain flat out cynicism about the political process. You can apply your own weights to these things but we worry most about the first and third.

Memo to the EU: markets work, capisce?

We've another of those stunning misunderstandings from Brussels about how this economy thing works. It's not so much the European Union itself, it's the mindset of the people that actually make the rules within it that matters. They've not got the idea that markets really do actually work. They've decided to set the fees that debit and credit cards can charge:

Consumers face cuts to the air miles, cash bonuses and other rewards they collect from credit cards because of a law passed in Brussels last month.Capital One, one of Britain's biggest card providers, has become the first firm to scrap the perks following new EU restrictions on the profits it can make.

In a statement the company said its cards, which paid customers up to 5p for every £1 spent, were "no longer sustainable".

If you look at the fees in isolation then you might well think, hey, they're making a lot, stop them! But to look at the fees in isolation is to be more than a bit of an idiot because markets really do work.

So, there's those fees. And then those consumers who think they're a bit high and would like to claw back some of that money get to do so. Because competition to gain those high fees means that card issuers start to offer cash back, air miles, discounts, freebies and other goodies. And what selection of freebies, discounts and other goodies people value most will influence their choice of card. Thus consumers get what they value most.

And now we fix the fees, to what in isolation might be regarded as "fair" and all those consumers then lose all of those compensating benefits. Because the people making these rules have looked at this in isolation, without noting that markets really do work and that card holders are already being compensated, in the manner they value most, for those seemingly high fees.

As we say, to look at such things in isolation is to be more than just a bit of an idiot.

Note that the profits that a card company can make are not being regulated. What is being regulated is the revenues one can have: and limiting the revenues that can be made also, inevitably, reduces the revenue that is rebated, leaving profits quite possibly unchanged. No overall benefit to consumers therefore but the tax leeches regulators feel they've achieved something.

This isn't, despite the well known views of at least one of us here, a complaint about the European Union. It's a complaint about the tax leeches regulators failing to understand that markets already achieve, without intervention, the things that the tax leeches regulators think that only they can bring about. The answer to which is, of course, more markets and fewer tax leeches.

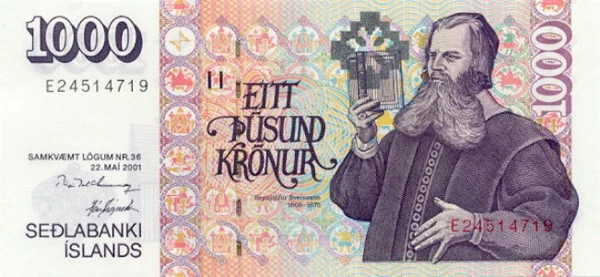

Iceland's new money and banking proposal. Yes, why not?

Iceland is considering a new report which would rather radically change the banking system of that country:

Iceland's government is considering a revolutionary monetary proposal - removing the power of commercial banks to create money and handing it to the central bank.The proposal, which would be a turnaround in the history of modern finance, was part of a report written by a lawmaker from the ruling centrist Progress Party, Frosti Sigurjonsson, entitled "A better monetary system for Iceland".

"The findings will be an important contribution to the upcoming discussion, here and elsewhere, on money creation and monetary policy," Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson said.

The report, commissioned by the premier, is aimed at putting an end to a monetary system in place through a slew of financial crises, including the latest one in 2008.

To be honest, the report (which can be read at that link) is little more than a rehash of the proposals of Positive Money. And worth about as much as such a rehash is going to be. It's worth pointing out that Julian Simon was actually correct, human ingenuity, and the knowledge it produces, is the ultimate resource. And given that Iceland's population is some 300,000 people there's not a great deal of it natively. We have noted around here more than once the problems that stem from trying to extract decent economic ideas from the rather larger population of Norfolk as an example.

The basic idea is that as banks create credit, credit creation is behind boom and bust, put credit creation into the hands of the government and abolish boom and bust. We don't think that that's how it will work out. Rather more likely is that politicians will follow the incentives of being able to spend this newly created money without having to tax to gain it and the result will be high and persistent inflation.

However, we're absolutely delighted that someone undertakes the experiment. Actually, we're delighted that someone else undertakes this experiment. Good luck to them say we. And we'll come back in 20 years, see whether there's been that abolition of boom and bust, been that persistent inflation or not, and then we can make a decision about whether to follow or not.

An interesting view of what bankers actually do

It's a commonplace in the public square these days that bankers are the evil ones, designing odd products like a CDS or CDO, to trap the unwary investor into parting with all their worldly wealth. and then there's the occasional expression of a more obviously sensible view, as in this one about Islamic banking:

Many of the instruments Irfan discusses were sold by major banks that saw them as just another opportunity. This is not surprising: Governments and wealthy individuals wanted financing that complied with their religious requirements, and banks gave it to them. Irfan, by contrast, longs for an Islamic finance industry that caters to “small and medium-sized enterprises, retail customers, the man in the street” and offers something “beneficial to everyone, irrespective of creed.”

The actual book is about Islamic financing, a subject we find quite fascinating. For of course the basis of said Islamic financing is an outright denial of something that we hold to be an obvious truth: there's a time value to money. That there is is what leads to there being an interest rate and also to all those other techniques like discounting to get to net present values and so on. We take these to be simply obvious truths about the universe that we humans inhabit and one can, as experiments have, derive the existence of that time value by studying small children. A baby doesn't get the idea of delayed gratification for greater gratification, a three year old will usually grasp the idea of two sweeties tomorrow instead of one now and a 6 year old might go for two in a week for one now. This is an interest rate and it does seem to be innate in human beings.

So, obviously, it could be seen as a little odd that we not only enjoy but thoroughly approve of these various Islamic alternatives. For they all (things like Sukuk bonds and so on) depend upon the absolute rejection of interest, that very thing that we insist is part of the fabric of our reality. The reason we so like Islamic finance is because all of he successful forms of it are actually constructs that, in the face of the religious insistence that there should be no interest, actually operate in a manner to ensure that there is a time value to money and that there is an interest rate, interest which has to be paid.

Which brings us back to what we liked about that description of banking: they bankers are simply providing what their customers want. Seems a more honest trade than many to us, enabling someone to meet their religious obligations while still saving for their old age and the like.

The problem with the bank levy and other Pigou taxes

This is both extremely disappointing and also par for the course:

The Liberal Democrats plan to hit the UK banking industry with an additional £1bn tax bill, which the party says will help eliminate the country’s deficit.

The supplementary charge will be in addition to the existing bank levy, which is on track to raise £8bn in this parliament, said Danny Alexander, the Liberal Democrat chief secretary to the Treasury.

The annual levy on banks, which was introduced in 2010, currently brings in around £2.5bn a year. Mr Alexander’s proposals are expected to take that up to £3.5bn a year.

The point is that the bank levy is a Pigou tax. There's an externality in the market which is not being included in prices. The tax is there to make sure that that externality is included in prices.

The externality is that the "too big to fail" banks receive, as they are too big for the government to allow them to fail, implicit deposit insurance over and above that on offer through the normal regulatory schemes to all deposit taking institutions. This means that they can finance themselves at lower than free market rates and it's the taxpayer that picks up the risk.

The solution, as we noted and praised when the levy was introduced, is to charge an insurance premium on those deposits that are insured in this manner. And that's how it does work: it's only on the deposits of the too big to fail banks, it's only on those deposits which are not insured through other schemes and it takes account of the riskiness of a run in said deposits (thus long term bond finance pays a lower rate than at sight deposits). That's all how it should be.

And the point about Pigou taxes is that it doesn't matter what happens to the revenue. Sure, it's nice to have 'n'all that, but the point is to correct the market, not to raise revenue.

Thus the idea that the rate should be changed in order to increase the revenue raised is nonsense. It's violating the very point and rationale for having the levy in the first place.

It's also entirely par for the course. No politician can see a potential revenue source without wanting to bathe in it. And that, sadly, is the problem with Pigou taxes. They're economically efficient, rational and make the world a better place. Until we come to the politicians who implement them when, over time, they will inevitably lose their original justification and simply become another method of gouging someone or other so as to bribe the electorate.

What's economically efficient, rational and making the world a better place when a Minister's seat is at risk at a looming election, eh?

Better to reverse QE than raise interest rates

That is, of course, a chart of the American, rather than UK, money supply. But much the same has happened to our own money supply under the same QE program. And it's also telling us that it would be better to reverse QE than it would be to raise interest rates. So the idea that that debt could just be cancelled doesn't fly we're afraid. We all know that at some point we're going to have decent economic growth again, unemployment will fall to a minimum (that frictional unemployment that reflects people changing jobs, not involuntary unemployment) and that then inflation will start to rise again. We all also know, because Milton Friedman told us so, that inflation is always a monetary phenomenon. And, finally, we all also know that base money creation is more inflationary than credit creation: or boosting M1 leads to more inflation than the same boosting of M4 would cause.

It's putting those all together that tells us that we should reverse QE. Think through the future: so, we get out of this liquidity trap, this zero lower bound. The velocity of money returns to something like normal. At which point we've got two choices as to how to reduce the accompanying inflation. One is to raise interest rates, the standard response. But that works on M4, it slows credit creation. We could also reduce that money supply by reducing M1: reversing QE. And as above, we think that shrinking M1 would have more effect on reducing inflation than reducing M4 would.

Another way of saying the same thing is that the amount we'd have to raise interest rates to choke off inflation will be higher if we don't reverse QE than if we do. And this will be true for decades to come as we gradually get back to the right sort of relationship in size between M1 and M4. Or, not reversing QE means that we have to accept more economic pain to reduce inflation than if we reverse QE. For decades.

Which rather puts the kibosh on that idea so trendy over on hte left. Which is that as one part of the government owns the debt of the government we could just cancel that debt and reduce the debt burden. But doing that permanently increases that base money supply and thus permanently increases the interest rates we'll need to slay inflation in the future.

So, reverse QE before raising interest rates.

You should be very careful what you wish for

An interesting little observation from Ed Lazear:

There are basically two ways that the average economywide wage can fall. There might be a shift in employment away from high-paying to lower-paying industries; in other words, the economy is producing more “bad jobs.” The other way is that the overall composition of work might be the same, but wages for the typical job in most sectors have fallen.

Normally, economywide wage changes reflect what happens to the wage of the typical job. But between 2010 and 2014 there were also significant declines in the proportion of the workforce employed in two high-paying industries. Those declines contributed to overall wage declines—and they may have been caused by policy mistakes.

The share of the private workforce employed in the BLS-defined industries “financial activities” and “hospitals” decreased by about 5% between 2010 and 2014. Jobs in these industries pay 29% and 24%, respectively, above the economy mean. Because a smaller share of labor is working those high-wage industries, the typical job in the economy is now lower-paying than in 2010.

What has been happening here in the UK?

Well, our highest paying industry by a long way is wholesale finance, The City. And for several years that industry was shrinking. And average wages were declining. The City is now expanding again and average wages are rising. It would not do to insist that all of both the rise and fall depends upon the hiring practices of The City. But certainly some of it does.

Which leaves us in a state of some amusement. For of course it is those who have been whingeing most about the domination of the financial markets who have been complaining loudest about the fall in wages. Be careful what you wish for for you might well get it.