Why does everyone want to subsidise the stuff that no one wants any more?

Here's another one of those terribly silly ideas that people keep having. People aren't using the High Street as much as they used to. Therefore everyone must be taxed more in order to subsidise that High Street that no fewer people want to use any more:

The Labour Party is considering a new secret tax on the high street to try to boost ailing town centres across the UK if it wins next year's General Election.

An advisory group created by Labour to consider the future of the high street has recommended that it looks at introducing a new levy on residents to fund a major expansion of Business Improvement Districts, which manage local areas.

In its report, which has been seen by The Telegraph, the High Street Advisory Group recommends “diversifying the application of BIDs, including the ability to assess property owners and residents” and says that “new tools will need to be explored which diversify income streams”.

Sigh.

OK, so hands up everyone, why are people using the High Street less?

Yes, correct, because some 11 to 12% of retail sales now take place on the internet. We thus require some 11 to 12% less retail space on a High Street. Or, if you wish to be picky, we require 11 to 12% fewer High Streets. So the idea of taxing the people who don't want to use High Streets as much as they used to in order to preserve those High Streets they no longer want to use is, well, it's ridiculous, isn't it? Akin to taxing Ford and GM to keep buggy whip makers in business.

But sadly it's not just ridiculous. For what do we also have a shortage of? Yes, you're right again, batting 1.0 so far. We have a shortage of housing in the centre of towns, where people like to live (OK, some people like to live, but enough people do that the point still stands). And what else have we got? That 11 to 12% of former retail space that has gone bust and is standing empty. Walls, roof, utility connections: bish bosh with a bit of plasterboard and some Dulux and we can convert one to the other. You know, this structural change stuff, where we move an extant asset from a lower valued use to a higher and thereby make the nation and society richer as a result?

And what is the response to this? Quite seriously there are people campaigning to deny change of planning use from retail (most especially the pubs that no one is allowed to smoke in any more, and are thus going bust) to homes and houses. That's not ridiculous that's just crazed lunacy.

Sigh.

Tempus mutandis and the extant infrastructure of the nation occasionally needs to be repurposed. The idea that we should tax everyone to set it in aspic is so, so, well, it could really only have come from politicians, couldn't it?

Why Uber might be making a mistake in paying by the hour

There's a little technical detail about incentives that suggests that Uber might be making a mistake in their policy of paying minicab drivers by the hour. That mistake being not quite getting the difference between the income effect and the substitution effect as it affects pieceworkers (those two effects together being what gives us the Laffer Curve of course). The point is mentioned here:

I've been chatting to local minicab drivers about Uber's operation in Manchester. They don't feel threatened, or tempted. Prices here start at £1.50, and wages are hard for even those VC types to undercut. Uber have allegedly been trying to do this with the bogus guarantee technique: drivers around here are apparently on £10.00 an hour, anything above that gets kicked back to Big Minicab. They don't fancy the deal. Even in slack times, when they're not being robbed of their reward moments, there's always the hope that a fare to the airport will show up, and that's part of what keeps you ferrying people around all day. It means you can (XXXX) toddle off home a bit early, which you can't do if you're on Uber's clock.

Uber, Lyft, Hurnya and whatever don't seem to realise that there's such a thing as a minicab work culture, intensely local and adapted both to the people who work in it and their customers.

Re those incentives: the income effect is the idea that we have a mental model of how much we want to earn in a day (or week, whatever). If we achieve that then we'll go home: or if taxes rise then we'll work more hours to make that target, if taxes on incomes fall then we'll work fewer hours. The other is the substitution effect where if taxes fall we'll work more hours as work now becomes more valuable to us than leisure and vice versa when taxes rise.

In general, across the economy, neither applies to us all all the time and both apply to some of us at least some of the time. It's the mixture of both, according to personal preference, that gives us that Laffer Curve.

However, detailed empirical studies have shown that pieceworkers (and taxi and minicab drivers are one of the groups that have been studied) tend to be more subject to that income effect. There's a definite mental model of how much they want to earn in a day and they'll keep going until it is earned then toddle off to do something more interesting. This is why you can never get a cab when it's raining of course: higher demand for cab rides means they earn their target earlier in hte day and thus, amazingly, an increase in demand leads to a reduction in supply.

Uber has thought this through with their surge pricing: in bad weather they increase prices and thus earnings to overcome this effect. But offering drivers a flat rate per hour is precisely and exactly the opposite and almost certainly isn't the correct response to that known propensity to the income effect.

This isn't the most amazing observation about the world, obviously, but it's an interesting little application of the microeconomics we know to be correct. Piece workers are more subject to the income effect than the substitution: thus hourly pay for them might not be quite as effective in attracting them as one might originally think.

As Herb Stein said, if something cannot go on forever then it won't

It's the Daily Mail that brings us the news that property prices have been rising by 8.6% a year for many decades now. This is of course a nominal number, not a post-inflation one, but projecting it outwards we see that there's going to be something of a problem in the future:

Children born today looking to buy their first home in 2048 will be required to pay a staggering £3.4million, according to new research.The remarkable figure was revealed in a study showing how decades of property value rises will affect a baby born today should the price increases continue on their currently trajectory.

The study was based on average annual increases of 8.6 per cent a year since 1954 and then uses this to pinpoint a cost for those buying their first home at the average age of 35.

Obviously, unless there's rather more inflation than we currently think is going to happen, that's not going to happen. Herb Stein will be right, something will happen to make this not happen.

But what will happen is the interesting bit. We hope that the solution will be a change in the way we plan housing in this country. For it's worth noting that this house price inflation really only started as the effects of the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act started to bite. In effect the government said that no one should build houses where people would like to go and live.

No, really, the 1930s were a time of an almost laissez faire attitude to who could build what where. And where people wanted to be able to buy should not be a surprise, they wanted to live in the countryside surrounding the towns and cities. That's how towns and cities had grown in England for centuries. We ended up with those ribbon developments across the South East, suburban semis along the major roads, little estates added to villages and towns within reasonable distance of London.

That's what people actually wanted, something we can see from the way people flocked to purchase these speculatively built homes. So what did the government do? Banned building what people actually wanted to live in. For of course we can't let the ghastly proles actually enjoy their lives, can we?

The solution to housing becoming too expensive is of course to reverse course on what it is that makes housing so expensive. Allow people to build houses where people actually want to live: in short abolish the Town and Country Planning Acts.

We'll get there, of course we will, for Stein was and is right. The only question is how long will the Nimby's be able to frustrate the desires of their fellow citizens?

This train fare question isn't difficult you know

The Guardian rather jumps the shark here:

The Guardian view on rail fares: unfair Travelling by train produces benefits for everyone – less air pollution, lower greenhouse gas emissions, fewer traffic jams. Passengers should not have to pay two-thirds of the cost

Actually, a small engined car with four people in it has lower emissions, lower pollution, than four people traveling by train. So it simply isn't true that everyone benefits from more train travel.

There are indeed some truths there though. It simply would not be possible to fill and empty London each day purely by private transport: some amount of commuting public transport is going to be necessary. And there's no reason why those who benefit from that should not pay for it: as they largely do through the subsidy of London Transport paid for by Londoners.

But on the larger question of who should pay for the railways of course it should be those who use the railways that pay for it. Some City fund manager who commutes in from 50 miles outside London should not have his lifestyle choice subsidised by the rest of us. We should not be taxing the man who cycles to work at minimum wage in order to pay for wealthier people top travel longer distances.

The Guardian is, once again, forgetting that there is no magic money tree. If rail users do not pay for the railways then there is no unowned cash that can be diverted to doing so. Either the rest of us put our hands in our pockets or we don't. And why should the poor pay taxes so the middles classes can live in the greenbelt?

A simple point on railway nationalisation

One point people bring up when they advocate renationalising railways (or renationalising stuff in general) is that when private companies run something they take a chunk of the total surplus in profit, but if the government were in control, that could go to them. But there's a very basic reason why this isn't the case: opportunity cost. A firm, in doing business, puts capital to use. It uses a mix of physical and human capital and devotes it toward achieving tasks in order, usually, to turn a profit.

The best way to measure the amount of capital tied up in a project is the market's assessment thereof—the firm's market capitalisation—although of course we know that market prices are never perfectly accurate, since they are only on their way to an ever-changing equilibrium, and they may not have got there yet. And what's more, not all the relevant information will always be in the public domain.

For rail franchises—or TOCs (Train Operating Companies), as they seem to call themselves—it is relatively hard to pinpoint the exact amount of capital they are using, as they are usually subdivisions of a larger structure. But suffice to say, running trains involves tying up money on the order of billions, whoever does it (i.e. it includes Directly Operated Railways, the state body that is currently running the East Coast Mainline pretty well). You have to rent the rolling stock (trains), pay the staff, buy the fuel, pay to use the track and so on.

From this capital you get a return. TOC margins average about 4% over the last ten years. The average company got more like 10%. FTSE100 companies seem to enjoy higher returns. Of course, operating profits are not share returns, but they tell more or less the same story. The extra couple dozen billion the government would need to spend on trains could equally be spent on equities or anywhere else for more or less the same risk-adjusted return. The return they got here could be put into trains.

But even doing this makes no sense. If the government returns that couple dozen billion to the population at large, the government can tax the income that the private citizens make on the wealth, at a glance dealing with the problems of governments holding wealth—principally: they are not very good at picking winners. Or they could pay off debt and reduce their repayment costs—since the risk-adjusted return of gilts is priced in just the same way as other assets.

Either way, and whether or not rail re-nationalisation makes sense from any other perspective, it is simply not the case that government, by nationalising rail, could get a bit of extra cash to put into our network.

What would we consider a successful railway system?

Under many measures, the railways have performed remarkably since privatisation. It is not surprising that the British public would nevertheless like to renationalise them, given how ignorant we know they are, but it's at least slightly surprising that large sections of the intelligentsia seem to agree.

Last year I wrote a very short piece on the issue, pointing out the basic facts: the UK has had two eras of private railways, both extremely successful, and a long period of extremely unsuccessful state control. Franchising probably isn't the ideal way of running the rail system privately, but it seems like even a relatively bad private system outperforms the state.

Short history: approximately free market in rail until 1913, built mainly with private capital. Government control/direction during the war. Government decides the railways aren't making enough profit in 1923 and reorganises them into bigger regional monopolies. These aren't very successful (in a very difficult macro environment) so it nationalises them—along with everything else—in the late 1940s.

By the 1960s the government runs railways into the ground to the point it essentially needs to destroy or mothball half the network. Government re-privatises the railways in 1995—at this point passenger journeys have reached half the level they were at in 1913. Within 15 years they've made back the ground lost in the previous eighty.

But maybe it's not privatisation that led to this growth. Let's consider some alternative hypotheses:

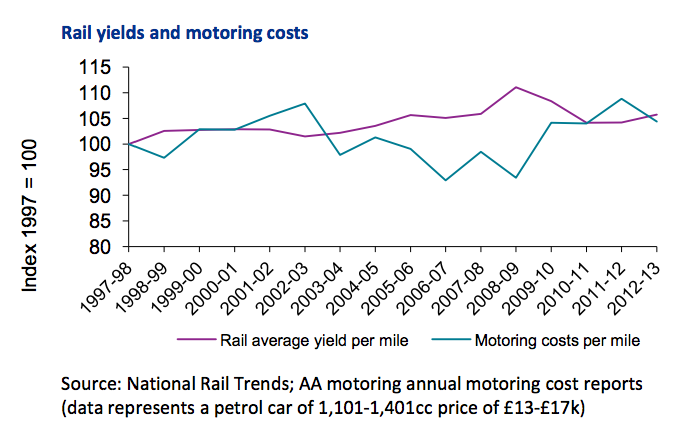

Was it a big rise in the cost of driving?

Was it the big rise in GDP over the period that did it?

Was it just something that was happening around the developed world?

Was it purely down to extra cash injections from the state?

Has it come at the expense of safety?

Has it come at the expense of customer satisfaction?

Has it come at the expense of freight?

Is it all driven by London?

Yes, planning regulations really have driven up house prices

Not that we ever suspected differently of course. But there are those who do insist that it's not planning regulations, who may build what and where, that increases the cost of housing in the UK. It's just some combination of rising population and perhaps not enough council houses or summat. Definitely not, it couldn't be, State restrictions on housing that make housing so expensive. So it's nice to see news of a paper that addresses exactly this question. What actually is it that has contributed to the sky high house prices of today?

What about the physical restrictions? In a hypothetical world where they could be magicked away, prices would be 15pc today lower than they would otherwise have been. The majority of these constraints can be felt in highly urbanised areas, for obvious reasons: there is not as much space available in city centres and lots in the countryside. Some parts of the country are easier to build on than others.

Everyone wanting to live in the South East, where all the jobs and money are, obviously has some effect. Housing is, at least in part, a positional good in that we can't all actually live in Central London. But that's not the only effect:

They find that house prices in England would have risen by about 100 percentage points fewer, after adjusting for consumer price inflation, from 1974 to 2008, in the absence of regulatory constraints to housebuilding. In other words, they would have shot up from £79,000 to £147,000, instead of £226,000. Another way of putting this is that prices would have been 35pc cheaper.

Had the south-east of England, in practice the most regulated English region, been as liberal as the North East, the least regulated over the past 40 years, house prices would still have been roughly 25pc lower. As it happens, the authors aren’t necessarily advocating deregulation: they are trying to calculate, using sophisticated econometric techniques and a wealth of detailed data, the effect of constraints.

The authors aren't advocating deregulation but of course we are. For example, those greenbelts where it's almost impossible to build houses cover rather more land than we have actually already covered with houses. Relax those restrictions and housing will become cheaper. To put the blame where it really lies, the reason British housing is so expensive is because the Town and Country Planning Act exists.

The most bizarre complaint yet about rising train fares

We've all, at some time or another, stood aghast when listening to one or another outbreak of lefty intemperance. The stamping of the foot as they insist upon absurdities like all people are born equal in every possible skill and talent, it's only society that makes us turn out different. Or to move from one of Danny Dorling's misconceptions of the world, how about Thomas Piketty's insistence on an 80% income tax plus an annual wealth tax in order to avoid the fate of France which is a country with a 75% income tax and an annual wealth tax. Or today's example, that it really is outrageous that rail fares should rise as subsidies to railways fall:

In reality, fare increases aren't really paying for infrastructure but are instead covering the gradual withdrawal of government subsidies, which have fallen by 9% in real terms since 2010-11.

Well, yes, and?

Agreed, we here think that privately run railroads are a wonderful idea, that's why we campaigned for that privatisation. We're aware that there's some people who don't agree with us on that too. But look at that specific reason that's being given. That it's right and proper that people be taxed in order to make middle class commuting cheaper. That the dustman must pay to subsidise the stockbrokers' travel in from Surrey. It's an absurdity when put that way but that is the argument being made. That it is somehow wrong that those who wish to live a long way from their work should pay their own costs of doing so.

How about that for an absurd insistence?

Goodbye, Green Belt!

Last night BBC London News aired a short film I took part in about the Green Belt. As part of a series of ‘authored’ pieces about various solutions to London’s housing crisis, I suggested that we should allow construction on the Green Belt around London to increase the supply of developable land.

Land, as Paul Cheshire likes to point out, is the key. The graph above shows how closely house price rises have tracked land price rises. Land-use restrictions on the Green Belt are quite strict: under the National Planning Policy Framework, local councils face a very high burden of proof to approve new developments on Green Belt land. If they were made less strict, then the supply of land and housing would increase and the price of both would fall.

Land, as Paul Cheshire likes to point out, is the key. The graph above shows how closely house price rises have tracked land price rises. Land-use restrictions on the Green Belt are quite strict: under the National Planning Policy Framework, local councils face a very high burden of proof to approve new developments on Green Belt land. If they were made less strict, then the supply of land and housing would increase and the price of both would fall.

I usually think of people who want to preserve the Green Belt as being motivated by financial considerations. If you own your house, you don’t want its value to fall, so you have a strong incentive to oppose any measure that will increase supply. Perhaps a large proportion of people involved in campaigns to ‘protect the Green Belt’ own their own homes. (And if not, that would certainly falsify this view.)

But filming with the BBC made me realize that this explanation is too neat and too unfair. The preservationist I interviewed, Dr Ann Goddard, was not preoccupied with preserving the value of her home – she believed, as many do, that relatively unspoiled natural areas are valuable and important to protect from development. The meadow she took us to was very pretty and I would regret losing places like it as well. Throughout our conversation Ann made it clear that her idea of England was entwined with its image as a ‘green and pleasant land’, not just somewhere for endless suburban sprawl.

Much of that greenery is worth keeping, but I suggest that the question is not ‘what’ but ‘where’. Since Green Belt land rings cities, it is much more difficult for city slickers to access than, say, gardens or parks. And lots of London already is covered in gardens or parks – more than half, according to one estimate. Allowing London to expand outwards would eat away at the Green Belt, but also allow more people to have gardens and for more (and bigger) parks to be built.

I also realized how important symbols can be: to Ann the meadow we went to WAS the Green Belt. If we’d taken her to a piece of intensive farmland (34% of the Green Belt around London) maybe she would have cared less about the prospect of that being turned into a village. And I wonder if focusing on intensive farmland is the key to changing people’s minds. In the end, if the battle over the Green Belt is about ideas and symbols rather than pocketbooks, a change of language might help us.

Why golf is a rubbish sport

The LSE's Paul Cheshire has a good post up on the Spatial Economics Research Centre blog today on green- and brown-field development. Among other things, he explains why there are so many golf courses on the green belt:

Nothing wrong with golf or horsey culture but what we have to understand is that Greenbelt designation gives those land uses a massive subsidy. House building cannot compete for agricultural land but golf and horses can. I recently discovered another reason why we have so many golf courses around our cities: they are substitutes for landfill sites. It costs £80 a ton to dispose of ‘inert material’ in registered landfill sites but nothing if it goes into building bunkers! To quote Paul Robinson, Derby Council’s Strategic Director for Neighbourhoods, in defending the potential to capitalise on the value of the sites of the Councils two golf courses: "Effectively you go out to the waste industry and you say we will allow you to put your inert waste in our golf course…So you create mounds and bunker areas using the waste and at the core of those is inert waste." .This is one factor which underlies the proliferation of golf courses close to sources of builders’ waste and on land where there is no competition from houses. As noted in The Economist there is a serious oversupply of them. So the combination of Greenbelt designation and landfill costs means we can build as many golf courses as the market demands at their subsidised price but we cannot build houses. It is time to start turning some of our excess supply of golf courses into gardens; with houses on them!

The whole thing is a good read, particular the estimate of how much greenfield land is currently available to build on within a ten minute walk of a train station. (Quite a lot.)