Why we vote

It’s difficult to understand why people vote, let alone why they vote the way they vote. No individual can reasonably expect her vote to determine or even influence the outcome of an election. In America, the chance of a one-vote victory margin that would determine the 2008 presidential election was about 1 in 10 million in some swing states, and 1 in a billion in places like California or Texas.

As Sam Dumitriu notes, this might still make voting worthwhile if you’re an altruist and you expect one candidate to make the world better than the other by more than a few billion dollars. But most people don’t think like this, and that has led some people to assume that voting is “expressive” – people do it to signal their allegiance to a particular tribe or team, not because they think the party they are voting for is best for themselves or the country.

Truthfully telling people you have voted certainly does seem to be a reason for voting, although the study the Freakonomics guys cite is from Switzerland, where I’ve heard they’re much more concerned with neighbourliness and civic duty than, thankfully, we are in England.

But does expressive voting determine how we vote? If it tells us anything it must mean that people are supporting parties or policies that, on some level, they believe to be counterproductive. Certainly if many (or any) people who are planning to vote Labour secretly believe that the Tories are actually best for the country, this would be a mark in favour of the expressive view of things.

In The Myth of the Rational Voter, Bryan Caplan argues that this is unlikely – people rarely feel good about voting for policies or parties that they think are bad. Group loyalty may well be a factor in determining how people decide what’s good to vote for, but surely it rarely trumps what people think is good.

In fact, barely half of each party's voters during the current UK election say they're proud to vote for their party. That obviously includes 'expressive' voters and people who like their party because they think it's the best one on its non-identidy merits.

Another problem with this view is that it also assumes that people realise that their votes don’t matter, but when polled people vastly overestimate the power of a single vote – the median American estimates that “there is a 1 in 1000 chance that their vote could change the outcome of a Presidential election” – the reality is between one in 10 million and one in a billion, remember. Yougov finds that “the less likely you are to think your vote will actually matter, the more likely you are to vote.” (I’m guessing this is because you’re more highly educated.)

That supports the idea that people vote for reasons of civic duty primarily, and for some people because they think their vote will affect the outcome of the election. For many people, no doubt, it’s both.

All of this may help us to understand why people vote the way they vote: is it mostly self-interestedly, as many public choice economist believe, or altruistically, as most political scientists believe? I will try to answer that in my next post.

Are EU scared?

One of the greatest fallacies of the Scottish independence referendum was that Scotland was being offered “independence”. Yes, we would have been independent in many respects. But the undisputed plan was to immediately begin re-acceding to the European Union.

Whatever this meant - from fulfilling requirements to become a member again to no longer being one of the big players (usually meaning France, Germany and the UK) with a greater say than the other nations - we certainly weren’t going to be independent.

It was not only concerning to witness it seldom questioned by Scottish people that we would be rejoining the EU - despite expecting an in/out EU referendum as part of the UK - but it is concerning, too, that the majority of pro-EU politicians don’t want to reform it or even to achieve a better deal for Britain.

What is more, there is a lot of scaremongering going on as fans of the European project say we couldn’t survive without many of our decisions being taken in Strasbourg.

A new report authored by Ewen Stewart, Stuart Coster and Brian Monteith seeks to dispel the myths about the UK’s survival without the EU and explains why a Brexit would not bring economic isolation to the UK as scaremongering claims by politicians suggest.

The paper has five arguments to show why often-repeated political claims are intimidating the British electorate into shutting their minds to the possibility of change and preventing a rational debate taking place:

1. In reality, the EU is more dependent on being able to export to our significant market than we are on selling to the European Single Market.

2. There is a real threat to UK employment, influence and broader prosperity if we do decide to remain an EU member.

3. Our future economic well-being depends instead on gaining access and selling to the faster-expanding markets that lie beyond the EU.

4. Employment growth would be even stronger if Britain was free to adopt bilateral arrangements of its own, outside membership of the EU.

5. A growing percentage of cross-border issues and regulatory requirements are determined now by bodies at the global level.

A lot of research is looked into about the UK's performance in comparison to that of the European Union. And the conclusion reached is that British jobs are not dependent on the EU and so this is no reason to leave. Jobs would in fact be gained by leaving the EU.

The UK has performed much more strongly over the last 6 and 12 year time horizons that EU averages while 14 out of our 20 fastest growing markets are with non-EU nations.

We have global links with the Americas, Asia and Africa, as well as the Commonwealth, meaning it is perfectly possible that the UK could have good trading relationships with not just our European neighbours but the rest of the world by enabling trade policy to be determined at home.

The political stability of the UK, the English language and the rule of law coupled with secure property rights and a population that is by far and away the most diverse in Europe mean we will always continue to benefit from global growth.

If the Scottish independence referendum is anything to go by - scaremongering a population about change can make the positive arguments shine and usually backfires. Hopefully it does.

Miliband's zero hours contracts catastrophe

Ed Miliband's latest attempt to screw up a part of the economy is his proposal to legislate on zero hour contracts:

"If you work regular hours for three months, Labour will give you a legal right to a regular contract, not a zero-hours contract."

I have no doubt Ed Miliband isn't ignorant of the fact that such a policy will harm lots of people and help only a tiny few, yet he doesn't seem to care two hoots - he supports the policy because he knows most people will endorse it based on the help for the tiny few while at the same time being wholly oblivious to the wider harm it will do. If you happen to be one of those few to whom that applies, you'll be happy. But for the vast majority, the labour market of supply and demand involves an allocation of resources (work and wages) far beyond the scope of any top-down management, and with far more efficiency than state meddling can achieve. Telling employers they must offer a regular contact after three months (a figure seemingly plucked out of the air) can only harm the efficiency of mutually allocated resources. This isn't anything more than standard first year economics - something politicians seem to be happy to ignore to buy votes.

What Ed Miliband is missing is the most important point. Yes, some people struggle on zero hours - the part of the labour market that contains much of this kind of work is often insecure, unstable and volatile anyway - but the notion that this law will make things better is moonshine. Here's the key point. The labour market of supply and demand is dictated by numerous price signals that generate all kinds of information about the value of labour, the supply of services, length of contracts, and so forth. A dentist can work in the same place for 15 years doing a similar number of hours each day. A sub-contracted painter and decorator can work at dozens of places in that time, with varying lengths of contract. Selling labour is heterogeneous - and you're just not going to be able enforce better pay or more stability without damaging a whole sub-section of people in that labour market.

So it's not that I'm repudiating Ed Miliband's proposal because I've suddenly developed amnesia about the struggles of people's ability to live or the volatility of the market - I'm repudiating it because its implementation will simply alter the behaviour of employees and employers in the market because the vital price signals of information on which the economy runs will be distorted.

It's easy to think of zero hour contracts only in terms of employees, and to imagine most employers to be cold, uncaring exploiters. But it distorts the true reality. Economic policies affect employers as well as employees - and employers are the essential providers in this equation. Make a law that helps low earners and you hinder another group (usually low-skilled employers but also other low earners). Make a law that helps tenants and you hurt another group (usually landlords). Make a law that helps Brits and you hurt another group (usually anyone who isn't a Brit). Nothing comes without a cost.

Employers have lots to consider when they take on people. They have to make forecasts about the future; they have to consider market fluctuations; they have to consider what they should invest; and they have to consider which future state-interference will hamstring them. Zero hour contracts are sometimes opportunities to exploit, but they are mostly opportunities to reduce risk in a frequently unstable market, and create lots of short-term employment.

Think who the beneficiaries might be - students, single parents, those looking for additional employment to top up their main job, and those with multiple part time jobs. The ability to work flexibly as and when they want is a very beneficial thing for them. Ed Miliband's proposal to ruin theirs and their employers' flexibility is narrow and short-sighted.

What Ed Miliband also doesn't understand is that the economic growth is the main vehicle to reduce zero hour contracts for those not happy with them. The reason being job growth increases the necessity for employee stability, which will only diminish the allure of zero hour contracts for both employers and employees, because employers are going to want stability in their personnel. Moreover, as unemployment rates fall and job creation continues to take place, greater power is transferred to jobseekers, which places selection pressure on firmsoffering less desirable contracts. Ironically, Ed Miliband's proposal will uproot some of the stability in the market, which will more than likely go on to have a cobra effect type scenario whereby he contributes to an increase in zero hour contracts - the very opposite of what he's trying to do.

The state's role is to reduce the tax burden for people on low incomes or in volatile parts of the market, and give them the financial help they require, leaving those vital price signals untouched.

Erm, this one is interesting

So Prof. Tim Besley of the London School of Economics, former All Souls Prize Fellow, ex-member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, the UK's third most respected economist, and all-round impressive smart guy, has a new paper with Marta Reynal-Querol at the Universtat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona. I mention these credentials to emphasise how respected and mainstream these guys are before I mention the finding of their paper, entitled "The Logic of Hereditary Rule: Theory and Evidence" (pdf, seems to be quite an early working paper), which is that hereditary rule/monarchy outperforms democracy but only when the hereditary ruler is subject to few constraints on their power.

Hereditary leadership has been an important feature of the political landscape throughout history. This paper argues that it can play a role in improving economic performance when it improves intertemporal incentives. We use a sample of leaders between 1848 and 2004 to show that economic growth is higher in polities with hereditary leaders but only when executive constraints are weak.

This finding is mirrored in policy outcomes which affect growth. There is also evidence that dynasties end when the economic performance of leaders is poor suggesting that hereditary rule is tolerated only where there are policy benefits. Finally, we focus on the case of monarchy where we find, using the gender of first-born children as instrument for monarchic succession, that monarchs increase growth.

That is: hereditary monarchs with lots of legal power choose better policy than other systems do, including democracies, non-hereditary dictators, and weak hereditary monarchs, and this is reflected in higher growth.

The size of the coefficient suggests that, in a country with weak executive constraints, going from a non-hereditary leader to an hereditary leader, increases the annual average economic growth of the country by 1.03 percentage points per year.

That's a really really big difference.

Of course, they're not saying they actually favour hereditary monarchy!

Although we have tried to understand the logic of hereditary rule, we do not regard the findings of the paper as supporting the institutions of hereditary rule. There are many arguments against, going back at least to Paine (1776), about the inherent injustice in such systems. Moreover, the fact that many polities around the world have put an end to hereditary rule and establish strong executive constraints is no accident since this is arguably a much more robust way to control leaders than relying on the chance that succession incentives will safe-guard the public interest.

It depends what you want government to do. If it's just there to guarantee a basic framework for society then as long as it worked, some sort of non-democratic system might be OK. Our having a stake in the electoral process hardly guarantees good governance (perhaps the opposite).

But lots of people value democracy not just because they think it gives us good policy: being part of a community; as an expression of human equality; an important type of positive freedom. These pragmatic arguments for and against different governance systems are not going to fully convince those types (and that's fair enough).

Of course the bigger issue is that the paper could easily be proved wrong in the review process, that's the point of interesting conjectures in working papers. And there's a whole lot of other literature out there, some of which goes against Besley and Reyna-Querol's work. But I tend to think that monarchy vs democracy is an empirical question. Whatever makes us freer, happier, richer is best.

The democratic cycle

Just as the business cycle seems to punctuate times of economic growth with periods of stagnation or recession, so there appears to be a political cycle in democratic countries, a cycle that features times of economic consolidation and progress with those of profligacy, deficit and debt. In some countries a centre right government coming into office institutes policies that rein in spending and encourage the growth of the private economy. Supply side policies aid business development and expansion, and tax cuts increase rewards and act as incentives to economic expansion.

The growth that often follows the policies can lead to the re-election of the government that implemented them. The feel-good factor of improving standards, higher wages and inflation under control can enable such a government to secure re-election.

Memories are short, however, in the democratic cycle, just as they are in the business cycle. People come to take wealth and growth for granted, and to be less prepared to continue with the policies that led to them. People grow careless and are more ready to take political risks.

Quite often a party that proposes to concentrate on distributing the new-found wealth rather than on continuing to grow it, appeals to the electorate more than the one whose policies helped bring it about.

The centre-right government is replaced by one that leans more to the left. It sets about expanding benefits and growing the public sector. It tries to exact more from private business by increasing taxes. It needs to fund new programmes and borrows money in order to do so. For a time its largesse is appreciated, but increasingly investment and business find it harder to flourish in the new environment it has created.

Growth slows down, the economy grows sluggish. People begin to feel less secure and less wealthy. They begin to question the competence of ministers who seem unable to manage the economy. The left-leaning government sometimes wins its first re-election after a term in office, but often with less enthusiasm than that which first put it there.

The economy stagnates under the impact of inappropriate policies, and a centre-right government is sometimes then elected to clear up the mess. It implements the policies that encourage investment, applies fiscal responsibility, and makes it easier and less costly for firms to take on new employees. Gradually the economy recovers, and the democratic cycle begins once again.

It might be a feature of democratic societies that whenever wealth and growth are created, a popular party will eventually secure election on the basis of promises to redistribute that wealth. The less well-off can always outvote the more well-off. It means that instead of a steady continuation of policies that allow the economy to grow, there is more likely to be a staccato, with periods that help the economy alternating with those that stunt it. This is more about politics than it is about economics.

The Spending Plan, courage, and politicians

A ring-fenced National Health Service, a bill poised to commit future governments to spend 0.7% of GNI on international aid, a triple lock on pensions, senior military figures pushing for commitments to higher defence spending: these are inauspicious times in which to contemplate cutting the UK’s £77 billion structural budget deficit, but contemplate we must. Aside from the velleities and equivocations of the political parties when it comes to their respective deficit reduction plans (and most other things besides), the Taxpayers’ Alliance has today released their Spending Plan, which comes as a substantial contribution to the debate. The Spending Plan’s first goal is modest: to lay out a menu of cuts which would take public spending to 35.2% of GDP by 2019-20 – the level forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility – its second more radical, to outline further measures which would cut spending to 31.7% of GDP, a level at which a single income tax of 30% could be implemented.

Despite the reasonableness of its first end point, or perhaps because of it, the Plan makes for sobering reading. An implementation of the first, less stringent, programme would, among other things, see the abolition of no less than three government departments (the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills; for Culture, Media and Sport; and of Energy and Climate Change), an end to national pay bargaining in the public sector, and a sizeable cut to Scotland’s grant from the UK government.

While the numbers add up, the issue is likely to arise in finding a politician willing to implement the proposals. As the TPA’s Chief Executive, Jonathan Isaby, puts it:

Our Spending Plan honestly sets out the savings that need to be made by whichever party or parties take power after the election. Today we challenge our political leaders to accept our plan or to produce a similarly rigorous set of proposals of their own which explain where it is that they would reduce spending instead.

The report recognises that reduced spending and deregulation are of no importance if they don't lead to people being better off in the long run, and makes the welcome case that making the state leaner is desirable for reasons other than deficit reduction. David B. Smith sets out the case that market economies grow faster, while the ASI's Director, Dr. Eamonn Butler, makes the ethical argument for lower taxes.

Despite the size of the challenge that future governments face, that markets have confidence in the UK’s ability to get its debt under control might serve as good evidence that all is, in fact, not lost. However, politicians would do well to come to the realisation that, whether those set out in The Spending Plan or not, radical decisions about the role of the state must be made; we can only hope this research helps them do that.

Ed Miliband's TV debates law

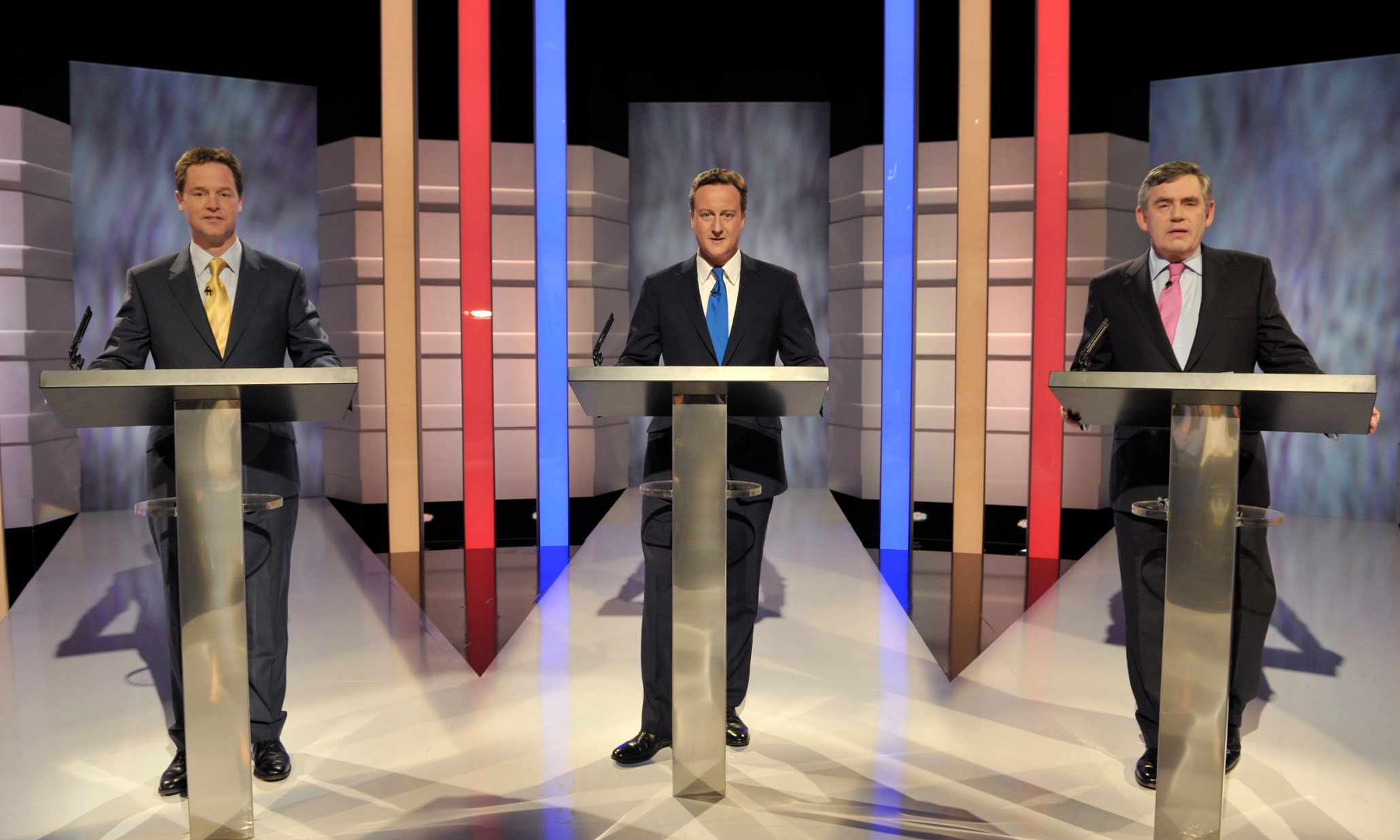

Following the TV debate row in the UK, Labour Party leader Ed Miliband says a future Labour government would pass a law to ensure that live television debates become permanent features of general election campaigns. The law would establish a trust to establish the dates, format, volume and participants. I was once shocked by the alacrity with which politicians proposed new laws as the answer to any problem. Then I came to see it more as an interesting fact of anthropology. Now I see it more as an art form. The invention that goes into making new, pointless or counterproductive laws is truly a pinnacle of human achievement.

It is sublime that a politician who cannot get other people to debate with him should propose a law to force them. Exquisite that this new law should be backed up and overseen by a new quango. Uplifting that the law's proponents should think that the process would be fair, democratic, and easy.

It won't, of course. As I have mentioned here before, it is by no means clear that TV debates have any place in the constitution of the UK. After all, we do not live under a presidential system, and we do not elect presidents at general elections. Rather, we elect individual Members of Parliament in our local constituencies, and it is those MPs, or at least their parties, who decide who goes into 10 Downing Street. TV debates, by contrast, suggest that we are in fact electing a head of government. They suggest that individual MPs are of no account, mere members of that person's Establishment. They suggest that we are electing an executive, not a legislature that can hold the executive to account. Already, the executive in the UK has far too much power over Parliament, and Parliament has too little control over the executive. TV debates can only make that imbalance more profound.

As for timing, who knows if the five-year fixed election cycle, introduced in 2010, will last? If parties split on key issues, for example, the country might find itself without a coherent government. The calls for a fresh election would be overwhelming. And how to decide who should debate anyway? Is it decided on the basis of current representation in Parliament (in which case UKIP, though polling 15%, would be nowhere)? Or on the basis of the polls (in which case the Lib Dems, currently part of the government, would be nowhere)? Should parties that stand in only part of the UK (the Scot Nats or the Ulster Unionists, for example) be represented in the national debate? If so, how deeply?

The only people who would win every time are the lawyers. I sometimes wonder if, like the mice in Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, it is actually for their benefit that the world is currently configured.

President Cameron and the TV debates

David Cameron's decision on the TV debates was one of the worst of his life. No, not yesterday's 'final offer' to the broadcasters of only one 90-minute debate with seven (or eight) parties represented, and held well before the start of the 'short campaign' prior to the General Election of 7 May. Rather, it was his decision to push for TV debates five years ago, when he was Leader of the Opposition, that caused the damage. In purely 'political' terms, that decision quickly back to bite him. It gave an opportunity to the Liberal Democrat leader, Nick Clegg, to come forward as the 'Anti-Westminster' candidate, boosting that party's standing and forcing the Conservatives into coalition.

TV debates of course always help the underdog and damage the government. So now that Cameron is Prime Minister, he is facing the same calls for debates from Labour and the smaller parties, and is having to take the same criticism he launched at PM Gordon Brown last time, that he is 'frit' of defending his record.

But there are two, more fundamental problems. The first is that there is no logical way to decide which parties should be represented in TV debates. The debates are, after all, seen as a 'national event', rather than some throw-away entertainment, so it is important that they should be fairly structured. But it is impossible to include all of the dozens of parties, including pop-up parties, who contest seats in the General Election. So where does one draw the line? The Liberal Democrats may be sharing power, but they are polling little better than the Greens. UKIP has come from almost nowhere, but now out-poll the Liberal Democrats, so should they be included at the expense of the LibDems? And the Democratic Unionist Party (and Sinn Fein for that matter) may well stand only in Northern Ireland, but they are key forces there, so should they be on the platform too?

There simply is no objective way to decide. And no answer is going to suit every party. (And it is for this same reason that taxpayer funding of political parties can never work either – unless the two biggest parties simply divide the funding up between them and resist any claims from 'upstarts').

The most serious problem, though, is a constitutional issue. Britain's governmental system is not supposed to be a Presidential one. True, the Prime Minister has many of the powers that a US President has, powers that once belonged to the monarch (like initiating wars and signing treaties, without troubling Parliament overmuch). But the Prime Minister is not just an executive, but still a member of the legislature - a Member of Parliament. When British voters go to the polls, they are supposed to be electing their local MP - someone who will actually hold the government to account. They might take into account what that might mean in terms of who moves in to 10 Downing Street, but in all but one constituency, that is not who they are electing.

There is an argument that the executive in Britain has too much power, precisely because it also controls the legislature. Of 650 MPs, a hundred are on the payroll, a hundred would like to be, and two hundred on the other side are lining themselves up with the same in mind. So party leaders and offers have enormous power, and Parliament has very little restraint on them. Maybe we should be separating the executive and legislative branches. Certainly, the last thing we should be doing is deepening the power of the executive further. But this is precisely the effect of TV debates. They focus attention on just one person, boosting centralism and central power. That is not healthy for any nation. Frankly, there should be no TV debates at all.

The BBC and the Election

It will be interesting to see how the Conservatives bear up under the relentlessly hostile BBC campaign coverage. It is not that the BBC openly praises Labour and its policies. What the BBC does do is to follow the Labour agenda of the stories they wish to focus upon. One week it is continuous coverage for several days of alleged failings and deficiencies in the NHS, perceived as a Labour issue. The next it highlights for several days allegations of "tax dodging" – a phrase they use to conceal the distinction between paying tax in accordance with the law, and criminal dishonesty in concealing earnings. Tax avoidance means organizing your affairs to lower your tax exposure in ways that the law allows and sometimes encourages. Tax evasion means not paying the tax you are required by law to pay. The words "tax dodging" and "tax dodgers" are used to conceal that distinction. Multi-millionaire Margaret Hodge wants people to pay what she thinks they ought to pay, rather than what the law requires them to pay. The BBC has given massive coverage to another area seen as a Labour issue.

The BBC also pursues a relentless anti-business campaign, highlighting what it sees as abuses by businesses, even where these, too, are within the law. Energy companies are castigated for not passing on falling wholesale prices, with never a mention of the time lag between energy companies buying wholesale and the delivery of that energy to customers. Stories focus not on the role of companies in creating jobs and wealth, but on their alleged abuse of their market position. Again, since the Conservatives are perceived to be more pro-business than Labour, the BBC is following the Labour agenda.

It is unlikely that the BBC is taking orders to highlight Labour issues every day, and much more likely that the BBC programme planners and presenters think like Labour does, and regard these issues as the important ones. There could just be some self-interest, too, with BBC planners thinking that a Labour government would probably give the BBC a more advantageous licence fee renewal deal than would a Conservative one. It will be interesting to see how effective their campaign is.

The nanny state's children

Scotland is seeing a hasty transfer of power from the people to the state. And a few components, including the SNP's unfaltering support from pro-independence voters that they expect to rely on for the near future, are making the transition happen with ease. Even in the face of a growing number of universally free things to adjust people to the state making our financial decisions, nothing of late has quite managed to reach the blatant level of state intrusion and awaken in people such fervent objection as the “named person” law.

This “service” means named persons will be assigned by the state to every child in the country until the age of 18. It is now set to be enforced in 2016 after the Children and Young People (Scotland) Act 2014 passed its final stages as a bill in the Scottish Parliament last year. Social workers, health workers and school teachers acting in a dual capacity of both their profession and as state informants, will have legal responsibilities that can rival those of the parent, while powers to intervene in private life and share personal information with government agencies will be handed to the state.

Educational charities and parents have joined forces under the banner of the NO2NP campaign and last week sought judicial review of the decision to enforce this law. By its opponents, the move is believed to be outwith the government’s legislative competence and to be incompatible with data protection rights and rights afforded to every citizen by the European Convention of Human Rights. In the judgement Lord Pentland said that the challenge brought before the Outer House of the Court of Session “failed on all points”, and approved the legislation. The campaigners expected there would be more than one hearing and so are not defeated as they consider their next legal steps to be heard by at least three judges in the Inner House.

It is important this policy is universal, proponents tell us, because children with additional support needs are not always immediately obvious to services and so this can ensure that intervention happens earlier to prevent crises at later stages in children's lives. A justification that has failed to quieten or satisfy parents’ concerns. But the creators of the legislation want to see it implemented at any expense. Even if it means creating bitter resentment among the vast majority of parents who are getting things right and do not want a named person overseeing everything they are doing.

State-dictated outcomes are presupposed to be superior to all else by the legislation. But parents do not necessarily agree. The one-size-fits-all approach neglects to consider the fact that parenting is unique to each family. Should "named persons", who don’t know children well, be given the authority to have a greater say than parents - in the eyes of the law - as to what their children ought to be doing then circumstances and behaviours may be misconstrued, leading to unwarranted consequences. It is understandable that more and more parents are viewing the legislation as a breach of their human rights. Their children are being assigned an informant to the state without the option to opt out.

The impact on parents is one thing. But teachers, too, who are required to be instrumental in this new dynamic, have no say nor even a choice in the matter. It has not been made clear when an educator stops being an educator and assumes the roles and responsibilities of the named person.

So when parents become suspicious of who they reveal information to, for fear that they are confiding in a middle-man between them and some investigator higher in the chain, more harm than good will be done. An environment of mistrust conducive to relationship breakdowns will be created. Not to mention the added time pressures and weight on teachers’ shoulders that the extra duties carry.

Early signs of the ostracising effects it will have are already visible in the Highlands where people were surprised to find it had been prematurely implemented as part of a pilot scheme. We are also seeing the wasted expenditure that this will entail, as referrals to services have risen.

To make social workers responsible for a population’s children is a costly blanket bureaucracy. And at a time when public services are under severe strain, it is ill-conceived that scarce resources should be drawn from the most vulnerable and urgent cases in order to pry on the 95% of families this legislation will never be necessary for. The case may have failed on all points thus far, but it is in the lack of justification by those behind it where we discover the greatest weaknesses.

Most strikingly important, though, is that every parent from the offset is being treated as potentially guilty of something until proven innocent. And they have to keep on proving their innocence until their child is an adult. It is a sinister state of affairs, indeed, when the onus lies on the general public to prove why we do not want legislation imposed on us.