Talkin' Bout a Revolution

Well, you know, if you say you want a revolution then you do need to understand what the others who might revolt with you are revolting against. And contrary to a popular misconception it isn't true that all who are willing to revolt against the current order are doing so for the same reasons you are. Or even trying to revolt in the same direction you are. We here at the ASI are of course in the vanguard of the neoliberal revolution, railing against the manner in which the State is captured by special interests, the way that regulatory capture depresses the economy, the way that civil liberties are whittled away in favour of a soft authoritarianism. I, Tim Worstall, am of course an extremist even by our local standards at Great Smith Street (one editor recently dismissed me from a publication on the grounds that I am a "hyperneoliberal" which by the genteel standards of American journalism I might well be). All of which is what makes this analysis in The Guardian so amusing to both I and us:

In the twilight of neoliberalism it's comics such as Russell Brand and Beppe Grillo who puncture establishment thinking.

It's entirely true that Beppe and Brand are railing against the current establishment.

Brand is not an isolated figure. In Italy the comedian Beppe Grillo has been the catalyst for the Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement), a populist, anti-corruption organisation which has tried to position itself outside of the traditional left-right paradigm.

Quite so. But to lump Brand and Grillo together is to entirely misunderstand what each is attempting to say. As far as Brand is concerned we seem to have the standard Teenage Trotskyism that most of us grow out of around our 16 th birhday and the discovery of the opposite sex. Beppe Grillo is a far more complex and interesting phenomenon.

For Beppe has been known to tweet on to his followers (the Movimento 5 Star operates largely through social media) pieces from myself, that hyperneoliberal. And anything more than a cursory glance at the movement's desires and policies show that they wish to move Italian society in a more neoliberal, or even just a more classically liberal, direction. They wish to cull parts of the State, kill off some of those special interests, revive civil liberties and reduce the regulatory capture that plagues Italy.

Just because some ponderous theorists decry neoliberalism it doesn't mean that all revolting against the current order share that analysis. It can be, indeed it is, true that some similarly decry the current state of affairs but are arguing for more of what the theorists decry. Grillo is outside the traditional left/right divide in Italian politics just as we here at the ASI are outside that traditional divide in British. We're both arguing that classical liberal polity, that set of policies that doesn't actually have a home in any of the traditional parties.

We might all be talkin' 'bout a revolution but it's not necessarily the same tables that we want to turn.

Gary Becker was right, part one: Crime

Gary Becker famously applied economic thinking to whole areas of activity that lie beyond the realm of narrow economic transactions. One such area is crime. The prevailing thinking of the day was that criminal activity derived from mental aberration or from social repression, and might be tackled by measures to improve mental health or to upgrade social conditions. In his paper "Crime and Punishment – An Economic Approach" (1968) and in subsequent publications, Becker advanced the alternative view that criminals were basically rent-seeking, trying to secure more of the resources that others produced instead of contributing to economic growth themselves. He posited that criminals are rational, performing a kind of cost-benefit analysis in which they set the gains they stand to make from a crime against the likelihood of being caught and facing a penalty.

Society can alter that cost-benefit equation in two ways, by increasing the likelihood of detection, or by increasing the penalties faced upon conviction. Increased police presence is by far the costlier of the two options, while jacking up the penalties can be relatively less costly to do.

Becker's insights have altered the way in which authorities tackle crime. Zero tolerance, for example, proposes that pursuit of minor offences ("broken windows") can create a climate in which potential criminals feel they are more likely to be caught. The use of CCTV to identify criminals by recording them in the act is similarly intended to raise the stakes of crime by making its detection seem more likely. On the other side of the equation the use of longer prison sentences also increases the costs that the potential criminal has to set against the benefits.

It was entirely typical of Becker, and part of his great contribution, that he took economics out from the economy itself and into the activities and relationships in society at large. Crime was one such area.

There's plenty of brownfield land but perhaps we don't want to build on it

A standard trope in the current arguments about planning permission is that we don't need or want to build on green belt land, or even unproductive agricultural land, because there's so much brownfield land lying around and available. Well, yes, this could be true but why would we want to poison people by sticking houses ontocontaminated land?

Hundreds of homeowners have been told their £400,000 properties could have been built on 'contaminated' land - and it's not safe for their children to play in the area. Environment officers at Tunbridge Wells Borough Council have warned residents of three streets in Paddock Wood, Kent, they may be at risk. They say 'potentially dangerous' chemicals including asbestos and creosote could have seeped in to the ground. The substances could have 'an impact on human health', they added.

This is land that used to be a timber treatment works. And a great deal of such brownfield land lying around the place is contaminated with one thing or another that we now think isn't all that wise to have lying around in a garden.

Fortunately, we do have a solution to this sort of problem. It involves that complex thing called "price". Along with the mystifying to many interactions of "markets".

We could, for example, have a rational and sensible system of planning to allow low density building where people actually want to live, as we outlined in Land Economy. There would then be that magical "price" stuff happening. Brownfield land that was, by virtue of location or ease of cleaning up, worth more than more rural land for building upon would get built upon. That which is not worth more than the costs of clean up would not. And so, by that miracle of "markets" we would be creating the most value possible by creating that valuable housing at the least cost. And, of course, the synonym for "creating the most value" is "making us all richer".

Plus we'd avoid the possibility of poisoning an entire generation of children by insisting that they live in houses built on polluted land.

Amazing what markets unconstrained by ridiculous regulation can achieve really.

What joy, it's Mariana Mazzucato again

We've pointed to Mariana Mazzucato's umm, interesting views on government aid to research before here. She seems not to have grasped the most basic concept underlying the very existence of such aid in the first place. But here she is wading in on what should be done about the Pfizer takeover offer for AstraZeneca:

Pfizer wants to buy AstroZeneca, a British firm, to cuts its high overheads and especially to pay the lower UK tax rate (20%) – the cheap way the UK attracts "capital"– rather than the 40% US tax rate

Given that the US rate is 35% we might assume that Ms. Mazzucato's command of the facts is somewhat lacking.

And what is happening to big pharma's research and development? In the name of "open innovation" – the admission that most of their knowledge comes from small biotech and large public labs – big pharma have been closing down their own R&D (reducing total numbers of researchers), as well as moving the remaining ones to be close to those labs. Big pharma is no longer in the innovation business, using its own resources to fund the high-risk ideas, most of which will fail. It has become more risk-averse and prefers to focus on the D of R&D and please shareholders. Mergers and acquisition strategies reduce expensive overheads and costs (of which research infrastructure is the highest).

And there is another, umm, mis-statement of the facts. It's the D in R&D that is the expensive and risky part of drug development. You'll not have much change out of $300 million (at the least!) for running a series of Phase II and Phase III trials of a new drug. And yes, drugs do indeed fail to get approved even after such tests, let alone during them. That's actually the function that big pharma performs in the current system: having the financial beef to be able to pay for this very expensive and high failure rate stage. She's simply got things the wrong way around here.

But we can and should go further for she's entirely garbling the whole point of having government contribute to the provision of public goods:

Government could also retain a golden share of the intellectual property rights (patents) which public research produces, and/or make sure that the prices of the new drugs reflect how the taxpayer paid for the most high-risk research.

Sigh. The entire point, the only point, to having government subsidise basic research is because basic research is a public good. That is, the results (ie, we know that heroin cures pain, Hurrah!) are non-rivalrous and non-excludable. This means that they are also extremely difficult to make any money out of. So, we assume that this difficulty with making a profit will lead to less innovation and research than we might like there to be. Great, so, government steps in to correct this possible market failure.

But you can't then go around demanding that government gets a cut of the profits when the only reason government is there in the first place is because it's dang hard to make profits out of this research. If it's easy to make profits then government doesn't need to fund it: the only reason for the government funding is that profits are hard to capture.

We can also think of this another way. The reason we have government is so that we can gain these public goods that we can only have through government. So to complain that government is producing public goods without any reward is near lunatic: that's just government doing what government is there to do. It's like complaining that your umbrella keeps the rain off you. Yes, what else do you want it to do for you, cook your tea or something?

Mervyn King on Thomas Piketty

In the Sunday Telegraph former Bank of England Governor, Mervyn King, reviews Thomas Piketty's book, "Capital in the Twenty-First Century," and carefully shows where and why it is wrong.

He points out that technology and globalization "have raised the demand for special talent and lowered it for unskilled labour." The Wimbledon prize money is 33 times what it was (in real terms) forty years ago, whereas manufacturing wages have merely doubled over the same period.

Returns go to the winners of the tournament, whether in tennis, finance, law, computing, advertising or other occupations. The “winner takes all” mentality has invaded many walks of life, although the identity of the winner changes over time.

King takes on Piketty's central claim that the rate of return on capital (r) exceeds the rate of economic growth (g), and his assumption that this will lead to ever greater concentration of wealth. King questions the idea that "the owners of capital reinvest all their profits and the spendthrift workers consume all their wages." Where, he asks, are the families that have pensions and own houses? And what about the sovereign wealth funds that are important forms of collective ownership?

A key issue King identifies in Piketty is his failure to take into account risk in investment. "Adjusting for risk," he says, "average rates of return have historically been much closer to growth rates." Indeed, King notes that the current risk-adjusted rate of interest is below the growth rate. Where Piketty claims that the period 1910-1970 was exceptional because of major shocks, King suggests that the risk premium "which constitutes a large part of the rate of return on capital," reflects the possibility that major shocks could happen again.

King tells us that the share owned by the top one percent has fluctuated up and down, but is lower today than it was 200 years ago, and "a similar story can be told for Britain and Sweden. In Europe, the concentration of wealth among the elite remains far below what it was in the 19th century."

Although Piketty concentrates on capitalism's alleged failings, King says one should not ignore the achievements of a market economy in creating growth and reducing poverty. Quite so. No-one has found a better way to raise living standards for billions of people. The wealth of a market economy has funded education, healthcare, sanitation, the arts and scientific research as well as raising material prosperity. Piketty's attack on it is but the latest in a series emanating from the Left, and King has done us all a service by undermining it.

Twelve problems with Piketty's capital

Piketty’s thesis is that the rate of return on capital exceeds the general rate of growth (r > g). So, barring wars, capital owners accumulate a larger and larger share of the world’s wealth. 1. This theory does not fit the facts. In the modern economy, it is not the rich who are getting richer, but the poor. The failure of communism and the spread of trade has lifted perhaps 2 billion people off dollar-a-day- poverty.

2. Capital is not like a tree that drops fruit into the owner’s lap. Capital has to be created, accumulated, applied, managed and safeguarded if it is to produce any income at all. Capital owners can and do fail at any one of those points.

3. Capital is certainly destroyed by war from time to time. But it is destroyed every day by folly, misfortune, miscalculation or being outperformed by competitors. The difficult thing is keeping wealth. Losing it is easy.

4. Capital carries risk, not a word that features much in Piketty. Utility-type capital with more predictable returns produces higher returns, entrepreneurs making risky investments demand higher returns. There is no one ‘r’.

5. Even a small amount of risk undermines Piketty’s belief that capital owners will get richer for ever. Stuff happens: it is hard to predict what returns will be next year, never mind in ten years or a hundred.

6. The risk-adjusted rate of return on capital is modest, and falling, as it has been doing for decades. Adjusted for risk, Piketty’s thesis does not fit the facts.

7. Capital is only one factor of production. You need labour and brains too. If capital took a larger and larger share, wages would soon be bid up. The 19th Century saw huge capital accumulation – but huge rises in living standards too.

8. The most important form of capital in our service economy is human capital. That’s not confined to a few rich people, but owned by all of us. Investing in it delivers a far bigger payback than the returns on financial or physical capital.

9. The success and rapid rise of poor immigrant groups, from Ellis Island to modern Europe, shows that you do not need to own financial or physical capital to generate income and accumulate wealth fast.

10. Capital-owning societies are actually more equal. Pre-tax, not greatly; but post-tax, with their health, education and welfare programmes, they are very much more equal. And it’s better to be poor in a rich capitalist country.

11. Piketty’s savage global redistribution would destroy capital, and sacrifice its productive power for society. Massive capital taxes create instability (Cyprus) or ruin (Zaire). High taxes also cut people’s investment in their own human capital.

12. If you want to make the world more equal, try open immigration. The world’s poorest live where capital is sparse and unprotected by the rule of law. Let them become participants in the productive, capitalist, wealth-creating process.

But George, it matters what people do, not what they feel guilty about

Sadly, George Monbiot has gone off on one again. Decrying the fact that we neoliberals in the Anglo Saxon capitalist style world don't feel guilty enough about despoiling Gaia. The poor in other places, being as they are not Anglo Saxon and also sanctified by their being poor, care a lot more.

We are sinners as a result.

The problem with this is that what matters rather more than how guilty any of us might feel is what we actually do.

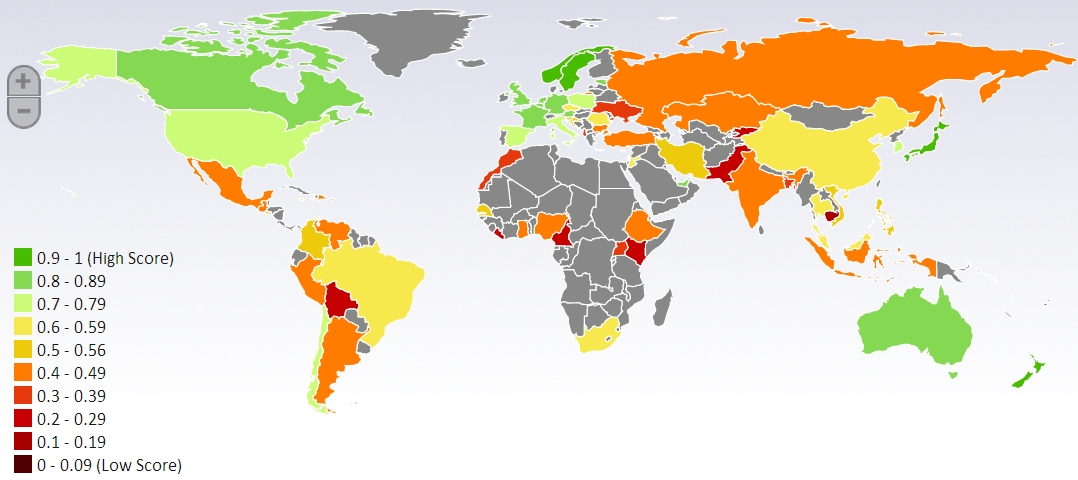

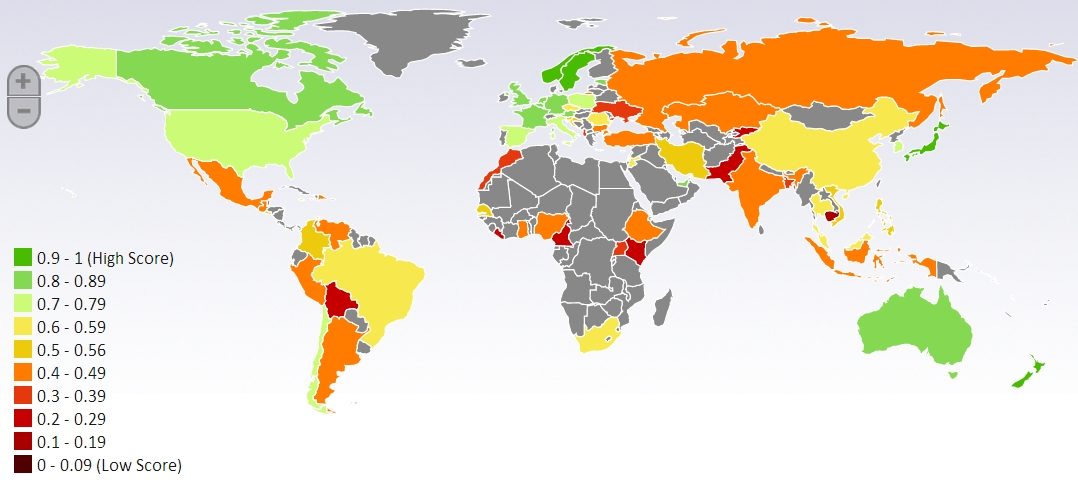

For years we've been told that people cannot afford to care about the natural world until they become rich; that only economic growth can save the biosphere, that civilisation marches towards enlightenment about our impacts on the living planet. The results suggest the opposite. As you can see from the following graph, the people consulted in poorer countries feel, on average, much guiltier about their impacts on the natural world than people in rich countries, even though those impacts tend to be smaller. Of the nations surveyed, the people of Germany, the US, Australia and Britain feel the least consumer guilt; the people of India, China, Mexico and Brazil the most. The more we consume, the less we feel. And maybe that doesn't just apply to guilt. Perhaps that's the point of our otherwise-pointless hyperconsumption: it smothers feeling. It might also be the effect of the constant bombardment of advertising and marketing. They seek to replace our attachments to people and place with attachments to objects: attachments which the next round of advertising then breaks in the hope of attaching us to a different set of objects. The richer we are and the more we consume, the more self-centred and careless of the lives of others we appear to become. Even if you somehow put aside the direct, physical impacts of rising consumption, it's hard to understand how anyone could imagine that economic growth is a formula for protecting the planet.

The problems with all of this are myriad. For a start, the impact of the poor upon the environment is much greater than that of we rich. The Amazon isn't being cut down to grow beef for McDonald's, it's being burnt down by poor peasants so they can grow runty corn for a year or two until the soil is exhausted. And the proof that we richer people do care more about the environment is all around us. Britain is cleaner than it has been for 500 years as a result of our increased wealth.

We might change out minds a little bit about this if we are to talk of climate change: for it is true that emissions from people living in the rich world are higher than of those living in the poor. But do also note what is happening: we rich world people are putting in place the expensive plans required to lower those emissions. Feed in tariffs, cap and trade, carbon taxes: whether you want to "take climate change seriously" or not is entirely up to you. But there's absolutely no doubt that it is us in the places that apparently don't care about it that are actually doing things about it.

Which brings us to the much more important basic point. The 20th century rather tells us that what people think about things, their guilt at the state of the world, is less important than their actions. Many communists and socialists really did believe that communism and socialism would be better for human beings than the terrors of capitalism and free markets. But their motives pale beside their actual works, slaughtering a hundred million and more in assuaging their guilt.

Actions George, not motives.

Repeat after us: the Treasury is not the economy and the economy is not the Treasury

We've another instance of that desperately sad confusion over the economy and the government, the difference between the Treasury and the nation. There are most assuredly people who go around paying and earning in cash and not, very naughtily, paying the requisite taxation on such sums. This will cost the Treasury tax revenue, this is entirely true. But it does not cost the nation or the economy anything:

For homeowners eager to save money on repairs, it’s a tempting proposition – you pay a tradesman cash-in-hand, he knocks a bit off the bill, and no questions are asked. With the builder or plumber failing to declare their earnings and pay any tax, such secret payments are said to cost the economy £2billion a year. Now a survey suggests the black economy is booming, with more than four in five homeowners admitting they have paid a workman cash-in-hand.

This simply is not a cost to the economy as a whole. For that money is still circulating, the economic activity is still happening, therefore it cannot be a cost to the economy. We might take it a little further too. We know very well that the levying of a tax reduces economic activity purely by being levied. The marginal deadweight cost at current levels of taxation is put at around one third or so. The corollary of that is that some one third of currently untaxed activity would simply not happen if it were taxed. The grey economy (intrinsically legal but untaxed) is thus in part an addition to the size of the economy we would have if all transactions were taxed.

But more important than that we have to insist on killing the pernicious idea that the economy is the Treasury, or that the Treasury is the economy. Economic activity that doesn't pay the tithe to the Treasury is still economic activity and thus is not a cost to the economy as a whole.

HMRC and the rule of law

Plans to allow Britain's tax authorities, HMRC, to take money directly from the accounts of tax delinquents have been criticised by a Committee of MPs on the grounds that HMRC 'sometimes makes mistakes'.

A sharper criticism would be that the plan is a fundamental assault on the rule of law.

Next year is the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, but the basic civil protections it gave citizens against arbitrary power are being systematically eroded. Governments have become elected dictatorships.

Magna Carta laid down that there could be no taxation without the 'common consent' of the people. It also insisted that no official can take anything from a person – nor fine them, nor imprison them, nor 'in any way destroy' them – without due process of law. Right now, the tax authorities would have to apply to the courts before they could take cash or other assets from a citizen.

But the new HMRC plans flout both these Magna Carta principles. HMRC can already decide that someone owes tax that they have deliberately 'avoided' – even if they have complied with every tax law. This is arbitrary power that we cannot safely entrust to any official. Reinforcing that power with further powers of confiscation – in the absence of any magistrate or court decision – is even more dangerous.

The MPs are right that even fair-minded officials make mistakes. Worse, the new plan passes the burden of proof – and the costs of proving it – from the authorities to the citizen. That again is contrary to the fundamental principle that people are innocent until proven guilty.

HMRC says that the new powers would be used only in extremis. But then they say that they expect perhaps 17,000 people will be affected each year. Many of them will, of course, be people who are completely innocent and the subject of official mistakes. Some will see their businesses ruined, and their employees losing their jobs, because of officials arbitrarily raiding their accounts. Others, worryingly will be people who the authorities decide to bully and make an 'example' of just because they are well known.

Recent history – like people being arrested under terrorism legislation for heckling the Home Secretary or walking down a cycle path – shows that when you give officials sweeping powers, they will be used. And when you exempt them from the rule of law, those powers will be abused.

Simon Jenkins is absolutely correct, the problem with the NHS is the national part

Glory be, something sensible said in The Guardian at last. Admittedly, it is being said by Simon Jenkins who does sometimes get things gloriously correct. His point is that the NHS simply cannot be run as one single monolithic bloc, it's just too large for that:

Yet one subject that is unmentionable – and therefore untouchable – is the size of the NHS itself. A public service that, for a generation, has successfully nationalised its virtues finds it has now nationalised blame for its vices. Where glory once shone down on the Commons dispatch box, now there is only scandal. It must make sense that, when every conceivable reform – devolution, centralisation, purchaser-provider split, internal markets, fundholders, commissioners – has been tried and seen to fail, someone should challenge the very concept of a central service. It might be worth looking at how others do it, and not smugly concluding that the public likes the NHS the way it is. The health service is not useless or uncaring or that bad at making people better. It is just too big. Aneurin Bevan was wrong to nationalise it back in 1948 – and his great foe, Herbert Morrison, was right in wanting a new service based on charitable and municipal hospitals, as remains the case almost everywhere in the world.

The NHS is some 11% of our entire economy. We might think that only running 11% of the economy as a Stalinist style top down and planned organisation isn't so bad. But this is an organisation the same size as the total economies of Finland, Greece or Portugal. And other than Seumas Milne there's no one at all left who thinks that rigid state planning of any organisation that size is likely to work or be efficient.

So, to localism and small scale management it is then. Jenkins mentions Denmark as a reasonable example, where it is the commune (as small as 10,000 people but usually substantially larger) that both raises the tax money for health care and also allocates its spending. Sweden does much the same but at the county level. And when the basis of the system is that fine grained then it's obvious that not all treatments can be provided by all outlets. There's therefore a considerable market in who provides what to whom.

And yes, that is the other side of pushing decision making and planning down to that level. We still want a coordination method for the whole. But we've just agreed that it cannot be central government nor planning. The answer is, thus, the other method of coordination that we know of: markets. For that is what markets are a method of, coordination, cooperation. The competition part of them is a terribly minor part: that's the bit where people work out who they are going to cooperate with.

A decentralised NHS would be, as Jenkins says, a better one. And we'd therefore need to use market mechanisms to provide the coordination across the different providers. It can still all be tax funded if that's how we decide we'd like to do it. But whether we do that or not it is still true that currently we've Stalnist central planning in an organisation that ios the economic size of entire countries. And the interesting lesson of the second half of the 20th century was that central planning on that scale just doesn't work.