The deep web, drug deals and distributed markets.

On Thursday a conglomeration of law enforcement agencies including the FBI, Homeland Security and Europol seized the deep web drug marketplace Silk Road 2.0, just over a year after the takedown of the original Silk Road site. San Franciscan Blake Benthall was arrested as site's alleged operator (under the alias ‘Defcon’), and charged with narcotics trafficking as well as conspiracy charges related to money laundering, computer hacking, and trafficking fraudulent documents. The authorities allege that Silk Road 2.0 had sales of $8million each month, around 150,000 active users, and had facilitated the distribution of hundreds of kilos of illegal drugs across the globe. The bust formed part of ‘Operation Onymous’, a ‘scorched-earth purge of the internet underground’ which led to the arrest of 17 people, the seizure of 414 hidden ‘.onion’ domains, and the shutdown of a number of other deep web markets. Law enforcement unsurprisingly refuse to reveal how they managed such a raid, leaving to some worry that they have been able to bypass the protections of the anonymizing software Tor, which is used to access deep web sites and to obscure users' identities and location.

Despite the success of Operation Onymous, many deep web markets remain online. Activists liken the shutdown of hidden marketplaces to a hydra: every time a site is taken down others spring up in their place, and thrive from the media publicity of busts. Indeed, the number of drug listings on hidden marketplaces has grown significantly following the takedown of the original Silk Road. Regardless, law enforcement is determined to stamp out the sites, with a representative from Europol warning “we’re a well-oiled machine. It won’t be risk-free to run services [like these] anymore’.

But what if there was no-one responsible for running such services? Sites like the Silk Roads met their demise because they have a centralized point of failure — get to the server and you can seize the site. Allegedly, cryptographic chunks of Silk Road 2.0’s source code had been pre-emptively distributed to 500 locations across the globe, to enable the site’s relaunch in the case of a takedown. Given the far-reaching impact of Operation Onymous, whether this happens or not remains to be seen.

To be truly immune to government takedown, a marketplace would have to have a decentralized, distributed structure, much like torrent networks and the bitcoin protocol. Enter OpenBazaar, which uses peer-to-peer technology to bring 'secure, decentralized markets to the masses.' In running the OpenBazaar program, each computer becomes a node in a distributed network where users can communicate directly with one another. A reputation system will allow even pseudonymous users to build up trust in their identity, and naturally, all transactions are done in bitcoin.

The biggest issues plaguing hidden marketplaces are those of trust and enforcement; if goods or payment fail to materialize, you can hardly just contact the authorities. Some sites get around this problem by offering an escrow service, with the money being centrally held until a buyer confirms their goods have arrived. The problem with this approach is that it leaves customer's money vulnerable to scams, hacks, and state seizure. With a decentralized system like OpenBazaar, no such central escrow system is possible. Instead, buyer and seller nominate a third party 'arbiter' (who could be another buyer, seller, or a professional arbiter for the site) to preside over the transaction. Payment is initially sent to a multi-signature bitcoin wallet, jointly controlled by the buyer, seller and arbiter. Funds can only be released from this account to the seller when 2 of the 3 signatories agree to it, allowing the arbiter to adjudicate any dispute.

In such a distributed system, there’s no central body to authorize posts and transactions. There’s also no central server to target. Law enforcement would have to go after all buyers, sellers and computers running the OpenBazaar software to bring the system down.

OpenBazaar is still in beta mode, with a full release expected in early 2015. Teething problems are likely and the design could prove problematic; even within highly decentralized systems there’s a tendency towards the concentration of power, and whilst robust, decentralized networks are often inefficient and expensive to maintain. There's no doubt the authorities are watching, though, and it will be interesting to see their reaction should OpenBazaar succeed.

The software is a re-work of the edgier DarkMarket concept developed at a Toronto hackathon earlier this year, and its developers are keen to highlight its use for selling things like outlawed books and unpasteurized milk over drugs and guns. Certainly, there's value in any global bitcoin marketplace which avoids punitive exchange rates and transfer fees, and like the Lex Mercatoria, can be relied on to provide a level of transactional security when state institutions can not. However, whatever its legitimate uses no state will be comfortable with the idea of a censorship-proof site. The problem for them is that they might just have to get used to it.

The problem with wealth taxes is that they don't actually work very well

The bit of that recent Piketty magnum opus that had economists scratching their heads was his demand for a wealth tax. For it's a standard commonplace within the subject that you really don't want to tax capital. Doing so makes the future a great deal poorer than it could be. Just like that old windows tax made the future a lot darker than it needed to be. There's an opportunity to explain why in some numbers being attributed to the likely effect of Red Ed's mansion tax:

Mansion tax could wipe an average of 5pc off homes worth more than £2m should Labour win the next general election and make the proposals a reality.The plans touted by the shadow chancellor, Ed Balls, could mean a 10pc drop for properties valued at £10m or more, and an 8pc fall for homes valued above £5m according to a new report from Savills.

The property group has also estimated a 6pc decline for those homes worth more than £3m.

People who own homes with a price tag above the £2m threshold could see their property value fall 4pc following Mr Balls' announcement that they will face a monthly levy of £250, a sum which gets progressively larger for more expensive properties.

£250 a month on a £2 million property is 0.15%. This drops the capital value of the asset under discussion by 5% or so. But the sort of wealth tax being demanded by Piketty is 1-2% annually, ten times larger than this tax. Now no, straight line predictions aren't all that good, there's changes in elasticity to consider, but it would be reasonable enough to think that a ten times the tax would have ten times the effect as a first stab at a guess.

So, in Piketty's desired world we'll be taxing wealth, or capital (they're rather the same thing) at 1.5% a year and thus the value of that capital, those bonds, stock and shares, that are being taxed will fall 50%. And that's why wealth taxes don't work very well. For consider the effect upon investment of a fall of 50% in the value of having made a successful investment.

It's still just as difficult to come up with a good business idea. It's still just as difficult to make that idea work, still just as expensive to make it do so. But the payoff from being one of the one in five that do manage to get something real going has just halved. Obviously, fewer people are going to make the effort and take the risks. Meaning that the future will be poorer by the lack of the effects of those new businesses that never were started.

Wealth taxes don't work very well for the simple reason that they make all our children poorer than they would have been even if they do make our children more equal. It's not a good bargain, not a good trade off.

There is no such thing as a gender pay gap

Actually, there is a gender pay gap, but the entirety of it is determined by 'legitimate' factors—things which make men's and women's labour different. As well as women having jobs they rate as more pleasant, and jobs that are objectively less risky, as well as doing more part-time work, women leave the labour market during crucial years, setting them substantially back in labour market terms. That is, the gap comes down to women's choices.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, since childcare seems to contribute to mothers' well-being and happiness, and looking after children is certainly not an unimportant task. But it implies that, whether or not society as a whole, through schools, culture, upbringing and so on, is the reason women do most of the labour in the home and in child rearing, firms are not discriminating against women.

Two new papers add to the formidable base of evidence for this conclusion. In "The Gender Pay Gap Across Countries: A Human Capital Approach", authors Solomon W. Polachek and Jun Xiang take a lifetime labour supply approach. They find that the wage gap increases with women's fertility, the size of the average age gap between men and women at marriage, and the top marginal tax rate, all things which affect women's total labour supply over their lives and at crucial points. (It decreases with the prevalence of collective bargaining).

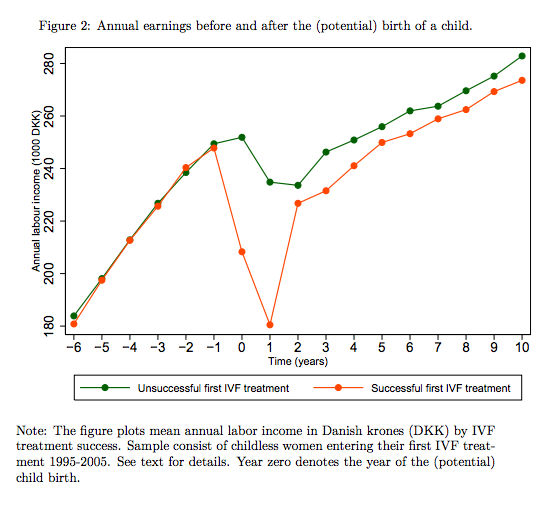

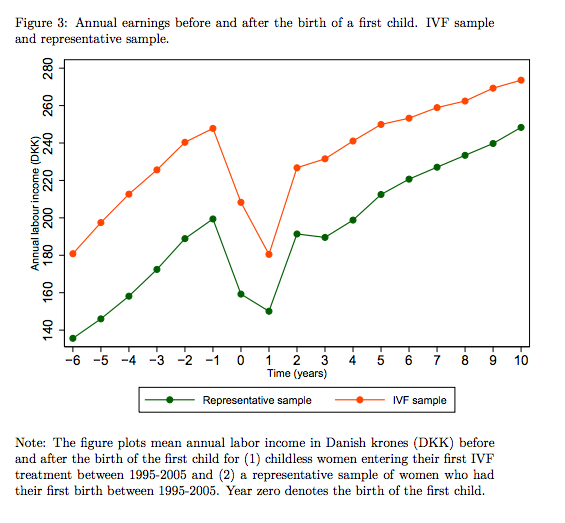

An even more interesting approach came in "Fertility Effects on Female Labor Supply: IV Evidence from IVF Treatments" by Petter Lundborg, Erik Plug and Astrid Würtz Rasmussen. To abstract from the possibility that women who decide to have kids have systematically different characteristics affecting what kind of career they'd have, they look at those who try to have children via In-Vitro Fertilisation (IVF):

This paper introduces a new IV strategy based on IVF induced fertility variation in childless families to estimate the causal effect of having children on female labor supply using IVF treated women in Denmark. Because observed chances of IVF success do not depend on labor market histories, IVF treatment success provides a plausible instrument for childbearing. Our IV estimates indicate that fertility effects are: (a) negative, large and long lasting; (b) much stronger at the extensive margin than at the intensive margin; and (c) similar for mothers, not treated with IVF, which suggests that IVF findings have a wider generalizability.

The results are pretty clear. Women are on a steady upward trajectory, likely in line with comparable men (as seen in previous studies). They then decide to take time out to have and raise children, and never make it back to their previous trend-line, perhaps moving to more flexible work or less demanding jobs. Even those who go back to similar careers are far behind in experience and have to catch up with movements they have missed.

So, while there might be such thing as a gender wage gap, the alternative is completely changing how children are raised in society, and while this would certainly have the potential to raise measured output, it may not necessarily raise total social welfare.

Social mobility is increasing but people are unhappy about this for some reason

This an extremely puzzling complaint:

More people are moving down, rather than up, the social ladder as the number of middle-class managerial and professional jobs shrinks, according to an Oxford University study.The experience of upward mobility – defined as a person ending up in an occupation of higher status than their father – has become less common in the past four decades, the study says, leaving children of those who benefited from it with worse prospects than their parents had.

Dr John Goldthorpe, a co-author of the study and Oxford sociologist, said: “For the first time in a long time, we have got a generation coming through education and into the jobs market whose chances of social advancement are not better than their parents, they are worse.”

Social class is not an absolute matter, it is a relative matter. Who is on top can change along with the structure of society: we've had versions where it's the very religious that are on top, where the good warriors are, where those with lots of land are and so on. But while which class it is has changed it's always been entirely obvious that they're of a "higher" class than the others. A relative matter rather than an absolute one.

Given this it is therefore also obviously true that if we've an increase in downward social mobility we must also be seeing an increase in upward social mobility. Because that social class thing is a relative, not an absolute, matter. And normally people cheer, or at least people like The Guardian cheer, when there's an increase in upward social mobility.

Can't think why they're not here.

We've actually tried negative income taxes, and they seem to work

The latest issue of Chicago magazine has a great piece on the 1970s experiments with the Negative Income Tax (NIT) including in the deprived city of Gary, Indiana (famous for being the birthplace of the Jacksons). Inspired by Milton Friedman, and in an effort to reduce time, effort and effort spent administering welfare as well as stigma in receiving it, some of the poorest residents of Gary and four other poor areas received cash in randomised controlled experiments.

A lot of research was done into the treatment groups in Gary and across the other NIT experiments.

One study found that kids born to mothers in the treatment group had birth weights 0.3-1.2lb higher. Another found significant and substantial improvements in reading scores for children in treated families. And what's more, kids whose families had been in the programme for a number of years performed significantly better than those in it for a shorter time. School performance also increased significantly across a wide variety of metrics for early-grade students in a rural experiment in North Carolina, although the effect did not appear in the other major experiment, in rural Iowa.

It's not clear exactly where this effect came from, but the most plausible source is probably better nutrition and spending the extra money on housing in better areas. Most of the evidence suggests that recipients did not spend their windfall on expensive consumption goods.

There were no overall robust effects on marital stability, but this was misreported, and the mistaken belief that the NIT had led to black families breaking up was a significant factor in killing the proposal as a political possibility under Richard Nixon.

However, as well as the effects seen, the experiments seemed to find that the income effect—having more money overall—outweighed the substitution effect—lower and more predictable effective marginal tax rates making it more attractive to work—especially when it came to women. A glance at the table below makes this clear.

But it's possible to conclude that the fall in the amount of labour those getting the NIT supply (something like 5% for the poor groups studied, and around 2% estimated for the population as a whole) is quite small, and within the bounds of what we'd be willing to accept to substantially reduce poverty.

What's more, there are countervailing factors. One issue is the level of the guaranteed income. Some of the families received were guaranteed an income 150% of the poverty line. With a benefit level closer to the existing system, merely structured more clearly and predictably, we might expect a weaker or even positive response (although we alleviate less poverty).

A second issue is the long-term response. If the negative income can counteract large environmental problems, allowing families to move away from pollution and feed their kids better and achieve more in school, we might see these people enjoy improved long-term life outcomes. Even looking at things from a narrow labour supply perspective, we know that more educated and more intelligent people supply more labour over their lives, so the long-term effect may be neutral.

(Tables sourced from Widerquist (2005))

Foundations of a Free Society wins 2014 Sir Antony Fisher International Memorial Award

I am quite chuffed. My short book Foundations of a Free Society has just won the 2014 Sir Antony Fisher International Memorial Award. Named after the late business and think-tank entrepreneur, goes annually to the think-tank that publishes the study that has made the greatest understanding to public understanding of the free society. That means the $10,000 prize goes to our good friends at the Institute of Economic Affairs, who published it, rather than to the author (sob!), but all power to them. The book was only published last November but has already gone into nine translations plus one overseas English edition.

Previous winners have included the bodies that published such books as How China Became Capitalist, by the Nobel economist Ronald Coase, and Prof James Tooley's hugely influential book about private-enterprise education in poor countries, The Beautiful Tree. So I am in excellent company.

It is a fine example of what can be done when think-tanks collaborate, each doing what they do best in a productive partnership. And I will be there in New York next week, collecting the silverware along with my friends and colleagues from the IEA.

Foundations of a Free Society is designed to explain what a free society is, for people who do not live in one (which is most of the planet, really) and cannot understand how a free society can be made to work. It is written in very straightforward, non-academic language, with no big footnotes and references and all that jazz – the sort of stuff that even a politician could understand.

It talks about rights and freedom and representative government, and toleration and justice and free speech and all the other principles of social and economic freedom. And it explains how and why a free society can run itself, without needing top-down control from some strong, dictatorial government. I hope therefore that it will help get these principles lodged in the mind of the upcoming generation, and give them the confidence to build genuinely free societies in their own countries around the planet.

Download a free copy of Foundations of a Free Society here.

Yes, of course Mariana Mazzucato is wrong, why do you ask?

Mariana Mazzucato is on a mission to persuade us all that as government provides all the lovely new technology and shiny shiny gadgetry we so enjoy then therefore we should all be coughing up a fee to said government for said shiny tech. There's a number of problems with this idea: one being the boring detail that government hasn't in fact been the source of all of that lovely research into tech:

I don't know about the CADC, but Tim Jackson's excellent book "Inside Intel" is very clear that the 4004 was a joint Intel-Busicom innovation, DARPA wasn't anywhere to be seen, TI's TMS 1000 was similarly an internal evolutionary development targeted at a range of industry products.Looking at a preview of Mazzucato's book via Amazon, it seems that her claims about state money being behind the microprocessor are because the US government funded the SEMATECH semiconductor technology consortium with $100 million per year. Note that SEMATECH was founded in 1986 by which point we already had the early 68000 microprocessors, and the first ARM designs (from the UK!) appeared in 1985. Both of these were recognisable predecessors of the various CPUs that have appeared in the iPhone - indeed up to the late iPhone 4 models they used an ARM design.

However, there's two logical errors with her claim which are much more important than the technical details of what she's claiming.

The first is that she doesn't seem to understand the economics of government spending on research very well. There's certain things that the markets, entirely unadorned, don't do very well. While much too much of this is made in general it's at least arguable that the provision of the public good of basic research is one of these things. And given that one of the reasons we have government in the first place is to provide those things, like public goods, that markets don't deal with well then her argument falls into something of a trap. For she's arguing that government should get a slice of the returns (through ownership of patents, of shares in companies that use government funded research) from the provision of that research.

But why? The very idea of government doing this work is that without government intervention we'll not get this public good. We pay our taxes, government provides the public good and we're done. There's nothing extra that should be done about it: assuming that government has done the research, the research is indeed valuable, we've now got here an example of government doing what it has already been paid to do. Hurrah, celebrations and bring out the marching bands etc. There is no logic at all to the idea that government should get two bites of the same cherry.

The second logical problem is that she's arguing that (and this is the real point of her work) the EU research budgets should end up owning a chunk of whatever it is that turns up of value from EU funded research. There must be commercial arrangements for Brussels to recoup some of the profits from the use of the results. And her clinching argument is that Darpa, the US military research budget, produces huge value from the research that it funds. Therefore we should do as they do.

The problem with this is that Darpa deliberately doesn't try to retain an ownership interest in technology derived from research that it funds. On the grounds that it just wants to produce the public goods of the results of that research and when it's done that its job is done. And it's also a great deal easier and more productive to give scientists grants to do research than it is to have arguments with them over ownership, in advance of any actual findings, of whatever the results might be.

That is, we're being advised to a) do as Darpa and b) not do as Darpa in the same sentence.

It's nonsense sadly, but influential nonsense.

Objectivism and modern society

Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged is polled to be the second most influential book in Americans' lives, coming in second only to the Bible. Whether this statistic is skewed or not, there is no doubt that Rand’s longest work has had a lasting impact on the hearts and minds of its readers since its publication in 1957. It may be too soon to know if it stands the test of time, but it has certainly persevered with power and passion. It’s hard to understand how Atlas Shrugged has remained so popular while the views of its author remain so controversial. Forget the left-wing masses—many self-proclaimed libertarians avoid being associated with her last name. In most circles (even sympathetic ones), the Randian badge is not worn openly.

Furthermore, she is consistently attacked by critics who paint her philosophy of objectivism as radical, rudely selfish and dangerous to modern society. When most people today—even on the right—recognise the need for some form of welfare or safety net, how can one include Rand’s voice in modern discourse?

At the ASI’s annual Ayn Rand Lecture on Monday night, guest speaker David Sokol addressed an audience of almost 300 attendees and reminded all of them why Atlas Shrugged transcends the criticisms and attacks on objectivism.

Unlike most philosophers and economists, Rand was able to connect philosophy and fiction in a way that inspired people to observe and revere the power of individualism. As Sokol pointed out, the right to have hope for yourself and whatever you choose to build is going to win against any promise a government can make.

Even in the 1950’s, Rand could see what direction governments was heading—that entrapments were disguised as promises, as governments increasingly encroached on individual's rights and property:

(Bureaucrat) Floyd Ferris:"You honest men are such a problem and such a headache. But we knew you'd slip sooner or later . . . [and break one of our regulations] . . . this is just what we wanted."

Rearden: "You seem to be pleased about it."

Ferris: "Don't I have good reason to be?"

Rearden: "But, after all, I did break one of your laws."

Ferris: "Well, what do you think they're there for?"

Ferris: "Did you really think that we want those laws to be observed? We want them broken.”

Today, some of the world’s most important leaders are looking to snare businesses, paint them as the enemy, and project the idea that the state is responsible for the success of business, job growth, and any individual achievement. It's an uncomfortable and deeply flawed narrative—and fortunately, not a particularly successful one. Regardless of bureaucratic narrative, Atlas Shrugged continues to inspire individuals in a way that collectivist approaches can't come close to; as such, Rand and her philosophy have secured their place in modern society.

To see photos of the ASI's Ayn Rand Lecture, click here.

Gordon Tullock: a great economist with no degree in economics

Following this approach, Tullock, Buchanan and fellow thinkers in the 'Virginia School', which focused on real world political institutions, realised that democratic processes were too often a very messy, exploitative and irrational way to make choices. They concluded that we should not be dewy-eyed about government decision making, and that we should limit it only to the things that are both crucial to do and simply cannot be done any other way.

Buchanan, in particular, emphasised the need for constitutional restraints so as to curb the exploitation of minorities by majorities, or of the silent majority by activist interest groups. On that front, Tullock will be particularly remembered for his delineation of the concept of Rent Seeking. The concept, and even the term, predated that work, but his contribution was to show how the cost of lobbying for government perks and privileges was economically inefficient and politically corrupt. He observed – the 'Tullock Paradox' – that the cost of rent seeking was often very low in proportion to the potential payoffs. A little lobbying can win potentially massive privileges (such as 'quality' regulation that effectively keeps out the competition). So it is no surprise that the lobbying industry has grown so large. And the more that government's range, power and tax take expands, the larger are the potential gains.

Many of Tullock's friends and colleagues were disappointed that he did not share in James M Buchanan's 1986 Nobel Prize. He never complained about it; and he will still be remembered with respect and affection.

Why not let rich people fund drug development directly?

That is, why not let ill rich people fund directly the research into a treatment that might cure them? That's the premise of this fascinating plutocratic proposal. That piece is very long, very detailed and walks you through almost all aspects of what is being offered. The essential idea is that, especially with cancers, there's a lot of weird ones that affect very few people. But there's quite a lot of rich people about and there's enough of them that, statistically, at least a few, a handful, of such rich people will get each and every one of those weird cancers.

This helps us to solve a certain problem that we've got with funding research into disease cures. We should, obviously, as a society be working on the low hanging fruit. A cure for something that kills 20,000 out of 100,000 people is worth a very great deal more in terms of human utility than a cure for something that kills 5 out of 100,000 people is. Tax funding of such research should therefore, again obviously, be concentrated on trying to find the cures for those widely suffered from diseases, not the weird and rare ones.

However, when we move from societal benefit to private benefit the numbers rather change. Someone suffering from one of those weird cancers is very interested indeed in a cure for that weird cancer. And some of those very interested people will be rich enough to fund the next step in the research. The step being talked about here is the movement of a likely looking treatment out of the lab and into Phase I clinical trials.

Those Phase I trials are where the first 10 or 50 people get given the treatment to see what it actually does to human beings. And there's a number of problems at this point. Neither tax money nor standard pharma investment cash is going to be very interested. One on the grounds that societal benefit will be greater with efforts made elsewhere, the other on the grounds that the final market simply isn't large enough to make it worthwhile. But of course rich people dying of the weird cancer face a different calculus.

The proposal is, at its simplest, just to allow said rich and ill people to pay for the Phase I trials (or some portion of them) in return for a guaranteed place on that very trial. They get this treatment that may cure them, 9 to 49 people get that same treatment without having had to pay anything and we all get the benefit of the advance in human knowledge.

Predictably this will cause howls of outrage in certain quarters. But we think that it's a fascinating idea: at the very least it's something that should be widely discussed and also in detail. No one is claiming that this is a perfect and final plan. Only that it's a very interesting one.

If we can harness the desire of rich people not to die to our goal of treating non-rich people dying of the same diseases then why the heck not?