So we're to have internal exile in the UK now, are we?

Welcome to the new land of freedom, liberty and human rights:

Terror suspects will be moved out of big cities and put into ‘external exile’ after a shock U-turn by Nick Clegg.The Deputy Prime Minister has agreed to re-instate the so-called power of relocation – which was scrapped in 2011 at the demand of his own Liberal Democrats.

At the time, one senior party figure labelled the measure ‘abhorrent’, ‘Stalinist’ and ‘authoritarian’.

But the abolition of the power has been blamed for two terror suspects absconding and, at a time of huge concern over jihadis returning from Syria, Mr Clegg has struck a deal with the Tories to allow its return.

Under legislation to be unveiled next week, the law will allow fanatics to be forcibly ordered to leave London, Birmingham, Manchester or other big cities to separate them from their extremist network.

They will then be made to live in more isolated rural towns identified by the Home Secretary, on the advice of MI5 and the security services.

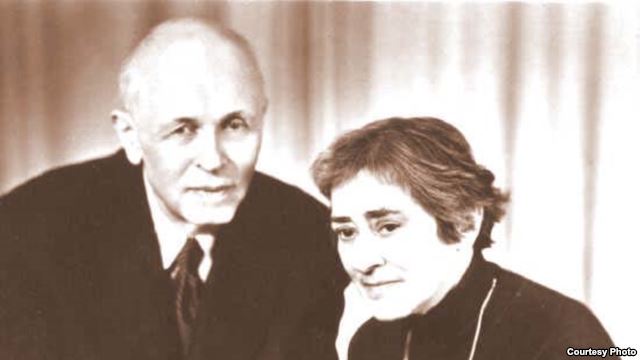

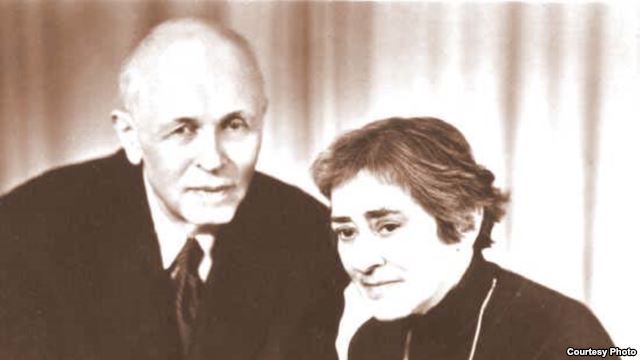

This is quite what the Soviets did and didn't we all complain when they did this to Andrei Sakharov and Yelena Bonner, sending them off to Gorky where they couldn't annoy the Muscovites any more. Various Fascist regimes, other communist regimes, had much the same sort of policy. Those who said things that the rulers didn't like got sent off to some rural backwater on the say so of the nomenklatura.

And the point about such systems is that they're meant to be examples of dystopias of various kinds, not a bloody handbook for how to run our own country.

It may well be that Abu Hookhand or whoever desires that we all be slaughtered in our beds until the Caliphate is established: but that still means that Hookhand or whoever should be, must be, accorded exactly the same rights a you or I have. Punishment can only come from having been charged, tried in an open court, with a jury, evidence, defence, a judge and the right of appeal right up through the system.

Do we individually and as a society face any danger from such extremists? Sure we do, they're opposed to almost all of the things that we think make up a decent society. But the danger from a few bearded nutters is as nothing to the risks of killing our own liberties in defence against them.

Either we have equal rights and liberties or we don't have rights and liberties at all, not ones that we'll be able to maintain.

Free Education? Don’t make the situation worse!

We love to moan about the system – how it conditions our thought, places expectations upon us, is inflexible and ill-suited to the modern context etc. – and that moaning isn’t limited purely to students. Free education sounds wonderful but, in reality, a subsidised higher education sector works against students’ best interests. The increasing supply of universities, places, graduates, qualifications etc. continuously devalue educational qualifications. With the exception of courses that have a significant vocational content such as Medicine, Engineering, Nursing, Teaching and Natural Sciences, many graduates will find their course’s academic content mostly unnecessary for the line of work they plan to enter. Unfortunately, an oversupply of graduates means that many firms advertise relatively well-compensated occupations as being exclusively ‘grad jobs’. This serves to reinforce the perception that you actually need a degree to even be capable of doing these jobs when, in actuality, it’s just that so many people currently have degrees that it’s pointless applying if you don’t. The necessary skills are better taught outside of a university.

What about all those who would essentially be coerced into going to university because, with free education and the increased supply of graduates, they’d have even less of a chance out there without a degree than they do now? What about those who left education earlier and whose relatively meagre qualifications are further devalued because of more graduates in the labour market? Funnily enough, the income inequality that education subsidies purport to alleviate would only increase. The training required to get a ‘good job’ (and, therefore, to fill them) would simply be lengthened due to qualifications’ devaluation. Normative signposting for how best to spend time is a subtle deprivation of civil liberty.

What is education? Why do we value one form of learning over another? Why stop at higher education? Why not subsidise gap years to Southeast Asia where people ‘discover themselves’? Subsidising one form of education almost always forcefully elevates it to a normatively superior perceived status; this perpetuates social structures, labour market characteristics, outcomes etc. since this normative dimension of legal institutions works to resist our attempts to reinvent social structures and deviating from the accepted norm. Does society really need to pay to offer free behavioural conditioning and thereby limit its own evolution? Free education protests are (mostly) unintended expressions of backward, socially destructive and misery-perpetuating conservatism veiled in social liberalism via equal opportunities and rights rhetoric.

Is private currency history repeating itself?

As I and others have said before, free banking & competitive currency provision either completely ignored, or unfairly dismissed by opponents who really don't know too much about the system. A recent example came on the FT's Alphaville blog. By author Izabella Kaminska, and entitled "Private money vs totally-public money, plus some history", it purported to show how cryptocurrency was just a rerun of earlier monetary struggles, looking specifically at the formation of the Bank of England:

As the BoE’s historical timeline helpfully points out, the BoE came into being when a private syndicate decided to risk all in 1688 by providing the UK government with funding when no-one else was prepared to do so. This ultimately proved to be a very good decision. It turns out lending money to government on terms you can enforce and control can be very profitable, especially if it leads to wise public investments that improve the wealth of the nation and make it easier to collect taxes as a result.

Soon enough the Bank’s success meant it could raise financing for both the government and private interests from almost anyone, issuing notes and deposits to all those who were prepared to do so.

Before the Bank knew it, its notes had become the most liquid and trusted in the land.

Open and shut then—free banking evolves naturally into superior central banking! Or maybe not. As George Selgin pointed out in the comments.

Ms. Kaminska goes out of her way to dismiss the famously efficient and stable Scottish system as an "oligopoly" without even bothering to offer any evidence that the banks in that system colluded or otherwise behaved differently than they might have had entry into the industry been unrestricted. (For her information on the Scottish system Ms. Kaminska relies on a single blog post that in turn draws on some untrustworthy sources, happily ignoring the extensive literature on the other side of the question.)

Ms. Kaminska then imagines that the English system's only fault lay, not in the dangerous concentration of privileges in the Bank of England, awarded it not owing to any enlightened concern about stability but simply in return for its fiscal support of the English government, but to the fact that that monopoly was as yet not complete! In fact a currency monopoly is extremely dangerous because it immunizes the monopoly bank from the normal discipline of routine settlement, making it capable of acting as a sort of Pied Piper to less privileged banks. (Peel's Act itself, in turn, caused trouble by undermining the English system's ability to accommodate changes in the British public's demand for currency.)

In light of these facts, Ms. Kaminska's claim that English banking crises were caused by smaller joint-stock note issuing rivals, which were at last allowed to compete with it, albeit only outside of the main, metropolitan market, beginning in 1833, is utterly--I was going to write "laughably" except there's nothing fun about it--mistaken, as she might have discovered had she bothered to read, say, Walter Bagehot's Lombard Street, say, instead of copying and pasting from the Bank of England's own self-serving web pages. She would there have come across Bagehot's careful account of how England's artificially centralized "one reserve" system, dominated by the Bank of England in consequences of its accumulated privileges, exposed it to financial crises to which Scotland and other less centralized ('"natural") banking systems were immune.

The winds of political change

UK by-elections (like last week's in Rochester and Strood, where the UK Independence Party gained its second MP) have always been an opportunity for electors to vent their contempt for the national politicians, before things return to normality at the general election. By-elections generally do not matter; general elections do. So voters' actions are perfectly rational. But few people, even the pollsters, are predicting that things will return to normal at the general election in May 2015. Though Scotland did not vote 'Yes' to independence in its recent referendum campaign, the performance of Labour, the main 'No' campaigners, was humiliatingly poor. But the Scottish National Party is now piling on support. It now has 90,000 members – roughly half the number that the Conservative and Labour parties are able to achieve, even though their UK-wide base is twelve times larger than Scotland alone. Again, the SNP has often done well in by-elections, but never managed to break through in UK national elections. But now there is a real feeling that normality will not return this time, and that the SNP will steal anything up to 40 Westminster seats from Labour.

The Liberal Democrats, the Conservatives' coalition partners in government, are meanwhile being humiliated just about everywhere. In the Rochester and Strood by-election, they lost their deposit for the eleventh time running, polling just a few hundred votes. Their core supporters think they have sold out to the Conservatives, while voters who want to send a rude message to Westminster have thought UKIP a much better way to do that. In the past they voted for the LibDems, but now the LibDems are part of the Westminster establishment that they despise.

The main parties, then, find themselves no longer leading the agenda; what will decide the election is how these minor parties fare in May 2015. But this phenomenon is not unique to Britain. All over Europe, minority parties are shaking the political class and winning footholds in the legislature.

What is going on, and why? Perhaps we have to look outside the political process to understand. In commerce, for example, traditional business models have been fundamentally disrupted by the internet. Retailing in particular has been rocked by new suppliers, new ways of shopping and new delivery systems. With things like Amazon Click & Collect, why do we need a Royal Mail – even a private one, as it is now. And much the same is happening in politics too. Small communities can find each other, and organise and mobilise, and cause real problems for the traditional parties.

Given today's technology, there is no reason for people to settle for off-the-peg goods and services. They can be made to your specification, and shipped direct to your door. Barriers to entry have been swept away, as new suppliers with new ideas and not much more than a website can suddenly enter the market and challenge the incumbents.

It is the same in politics. When people have a choice of umpteen different TV or phone or utility packages, they become increasingly contemptuous of national and local government 'take it or leave it' services. When Air B&B or Über enables people to access services in an instant, they wonder why they have to fill in forms and queue up in council offices. What is the point of a Met Office when you can get the weather on your phone from countless other providers?

And national parties find it harder to dominate the national debate, as newspaper sales have been falling, because more and more people get their news from online channels – and not necessarily from the traditional media companies, but from a huge number of new media channels, plus (increasingly) social media and other sources. Activist groups can find each other and mobilise. The domination of traditional media and traditional parties is being eroded by people power.

Through internet and communications technology, we can also bypass government services more easily. Telephones were a nationalised industry thirty years ago, but nobody even thinks about re-nationalising them today. And given the new multiplicity of information and entertainment channels, more and more people are asking why we really need the BBC – that one-time flagship of the British establishment – as a state broadcaster.

The internet also makes it easier to find a private doctor or a private tutor, or indeed to find a job and an apartment. Self-help groups provide help to patients or parents that the lumbering government systems simply cannot provide. Who needs government?

Not many of us, any more. Nearly as many people in the UK (176,632) told the census that their religion was Jedi than there are currently members of the Conservative Party. With falling memberships, party candidates are becoming increasingly irrelevant to most people. They are chosen by a dwindling core of of grey-haired Conservative activists or hard-line-socialist Labour ones, with outdated, intolerant or patronising policies to match.

The politicians' response has not been to understand these new trends (their attempted use of social media is, as we have seen recently, usually disastrous) but to insulate themselves. Politics is no longer something that successful people in other fields did for a few years as a service to their country, but a full-time career, carefully preserved as such.

No wonder people are upsetting their applecart. And no wonder that they cannot understand why.

Are our children safe with Children’s Services?

The great majority of those who work in local authority children’s services do the very best they can in very difficult conditions. They suffer abuse from the parents with whom they deal and the media, poor management, criticism from Ofsted and, from their perspective, inadequate resources. What’s more, neither they nor anyone else know how well they are performing. In 2003, the Laming Report made a huge number of recommendations. The body of their report made it clear that there was too much process (bureaucracy) and too little time with the problem families. Performance was assessed by activity (paperwork) and not by outcomes; the body of the report called for that to be reversed. But outcomes did not feature in the actual recommendations which, ironically, focused on increasing the bureaucracy and made matters worse.

In the eleven years since, government has recognised that performance should be measured by outcomes and some limited progress has been made, e.g. for adoption services. But where child protection is concerned, we simply get lip service. No outcome measures have been suggested, nor the specific metrics, nor how they should be gathered. In short we have no idea what “success” in child protection would look like or which local authorities are doing better than others.

When, last month, I asked the Children’s Department Minister, Edward Timpson MP, about performance measurement in this area, the answer was that they had turned the whole matter over to Ofsted. The rest of his letter discussed the bureaucracy involved but there was not a word about how performance should be assessed.

This is, of course, a cop out: Ofsted should measure performance against standards set by government, as it does for schools. Government is responsible for specifying what it wants in return for our money. How else can they know whether to spend more or less?

Both Ofted’s “Framework and evaluation schedule” (published this June) and Rotherham inspection (published last week) have many references to the importance of measuring outcomes but nothing about what outcomes should be desired, what the metrics should be nor how they could or should be collected. One has to feel some sympathy for the Rotherham local authority for being chastised for failing to do something that no-one has explained, not even the Department responsible.

Our children may or may not be safe with Children’s Services. The bigger question is whether they are safe with this government.

Well, yes Sir Simon, but how do we calculate this?

Simon Jenkins is reviving the notion that clever people like himself, those Great and the Good, can tell all of the rest of us how to live our lives. His particular example is supermarkets but it could be anything at all really, given the proclivities of some to tell other people what to do. We went from that High Street thing, to supermarkets, to out of town supermarkets and perhaps now to online sales:

Land is Britain’s most precious resource. The point of planning is to economise its usefulness.

We'd argue a bit there, Britain's most precious resource is Britons. Their, our, accumulated knowledge, labour and the accumulated labour (also known as capital) handed down from our forefathers. But that aside, yes, of course, we wish to create the maximum economic benefit from whatever resources we have (and that does not mean just money, of course not, we're talking utility here).

At which point we've got to ponder, well, how do we do that maximisation? And the truth is no one knows. That's why we cannot plan. Should someone, in the 1980s, when considering a planning application for a supermarket have predicted the rise of the internet, Amazon and Ocado? Could they have done so? In the 1990s?

Yes? No?

If not, then it couldn't have been planned for, could it?

At present, smart planning ought to be thinking ahead of the boom in online shopping. What mistakes might there be in pandering to its gargantuan appetites? What are the implications of every street jammed with home delivery lorries? What of every suburb blighted with distribution centres, supplied by giant hangars littering every motorway?

The correct answer here is "we dunno". Nor do you and nor does anyone else. We're all just going to have to suck it and see. Or, as we might put that a little more formally, allow the market to sort it all out. We consumers will work out which of the various options we ourselves prefer, those who cater to our desires will prosper and we'll end up with a system that might not exult entirely everyone but which does the best to provide aggregate human utility that can be managed at this stage of technological progress.

And yes, that does mean that Sir Simon and his ilk don't get to plan it all for us. Exactly what annoys them all so much of course.

Firms can pay us to recycle

Recycling comes more instinctively for those on low incomes and who live in low-income countries compared to their respective high-income counterparts. To increase the amount that we recycle and conserve, we must privatise the process and enable private companies to people for recyclable goods. In many areas, if people put out more goods for recycling than their allotted quota, the local authorities refuse to collect it. Private companies, however, have incentives to collect as much as they can and would do otherwise. By further incentivising households via fair compensation, we could significantly increase the rate of recycling. Furthermore, why should we, as suppliers of recyclable goods, be expected to hand over our products for free?

Also, given the tough socioeconomic climate, extra income derived by providing an additional, monetary reward to households that recycle whilst cutting government expenditure would be helpful.

People who recycle out of necessity are aware of the economic value of those goods; in India, consumers are paid to hand over their recyclable goods such as glass bottles, plastics, newspapers, etc. by various private companies and this initiative is practiced voluntarily across society due to the mutual financial benefits it incurs. In the UK, there are some places where we can ‘cash in’ our bottles, cans and newspapers but they are few and far between – it is also inconvenient for us as suppliers. Furthermore, if firms in India are able to collect from peoples’ houses and also pay for those goods, why are our firms unable to do the same? One reason could be that India has a relatively flexible labour market and lower wages. However, even though higher wages are prevalent in Britain, relatively advanced technology can still make this feasible by keeping costs down and financially rewarding those whom they procure goods from. Alternatively, and preferably, we could ease up on immigration restrictions a bit more, remove the minimum wage and instantly make this business model feasible.

In the UK, the financial benefits of recycling are neither directly felt by the consumer nor properly managed by the collection authority. Instead, it is squandered by inefficient management and stunted by unfair outcomes. If government continues to subsidise and undertake this activity then this inefficiency and its corresponding sub-potential recycling volume will continue.

Can we stop talking about the alleged 'gender wage gap' now?

Many are boasting good news on the ‘gender wage gap’—I agree, it’s great news: the Office for National Statistics’ findings offer more proof that wage gaps have very little to do with gender, and much more to do with choices each gender is prone to make. From the BBC:

The average full-time pay gap between men and women is at its narrowest since comparative records began in 1997, official figures show.

The difference stood at 9.4% in April compared with 10% a year earlier, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said, a gap of about £100 a week.

This as well:

Hourly earnings figures reveal that, in April 2014, women working for more than 30 hours a week were actually paid 1.1% more than men in the 22 to 29 age bracket and, for the first time were also paid more in the 30 to 39 age bracket…

…The government said that, from next year, it was extending the rights for shared parental leave. It had also invested in training and mentoring for women to move into higher skilled, higher paid jobs, and guidance to women looking to compare their salaries with male counterparts.

Women, from the start of their careers, are now earning a higher salary than men; and, if they choose to make the decision to stay in the work force, they are more likely to be promoted than their male counterparts as well.The real gap, it seems, is not between women and men, but between mothers and child-less women. Leaving a job early on in one's career or for an extended period of time to have children will impact a women’s salary when she returns to the work force.

As this is the case, I think the government is probably right to extend rights for shared parental leave (though the money put into training will surely be a waste; women who are ambitious and attracted to careers in science, business, and formerly male-dominated sectors aren’t having much trouble pursuing them). But anything legislated from the top-down can only go so far to change cultural opinions that have been in place for centuries about the role of women and the household.

In reality, women’s choice in their private and home lives will be the greatest determinate as to what further changes we see in wage gaps. It seems there's evidence that good economic climates actually lead more women to stay at home with their kids rather to go out and get jobs - at the same time, we are witnessing an increase in stay-at-home-dads, which, most likely, has multiple reasoning to it: more women are demanding to work, and more men feel comfortable making the choice to stay home.

Either way, it seems there is no obvious discrimination between men and women when they enter the work place; as far the element of motherhood is concerned, we should be less focused on the numbers and far more focused on ensuring that women are not being socially pressured, either way, to make any decision that is not completely their own.

As we've said before there's something a little odd about UK inequality

We're often told that the UK is one of the most unequal countries in Europe. We're also often told that this is bad, very bad, and something must be done. We've pointed out a number of times that there's another difference in the UK economy, something that makes us rather different from other European economies. And that's the massive importance of London in our economy. In the latest release of figures from the ONS we can see this quite clearly too:

The UK's highest earners live in Wandsworth, Westminster, and Richmond upon Thames - all in London.The weekly wage of the average worker in those areas was £660.90, £655.70 and £655 respectively in April 2014.

At the other end of the spectrum, the average weekly earnings of someone in West Somerset were just £287.30.

The ONS prefers to use the median as its measure of average earnings “as it is less affected by a relatively small number of very high earners and the skewed distribution of earnings”.

Because we're using the median we're not just recording those bankers in the City there. This is the number which 50% of the people earn more than and 50% less than in each area. And a goodly part of that recorded UK inequality is because of these regional differences in income.

It's also true that living costs vary wildly across the country. Most especially housing costs of course although that's not all. London prices for a pint would choke a fellow from West Somerset just as much as rents or house prices would do.

Given that this is all so then actual inequality is rather lower than we're always told it it. For, of course, we should, if we're going to be concerned about inequality at all, be concerned about inequality of consumption. And if people in one part of the country have higher wages but also face higher living costs then that's an inequality that shouldn't be concerning us.

In no other European country is the capital such a dominant force or influence in the economy,. Thus our inequality is different from their: and arguably our inequality is lower than it is elsewhere, given this specific difference.

Why we should cut alcohol and tobacco taxes and why we can’t

The socioeconomic profile of drinkers and smokers across countries are similar. Smoking and drinking is more prevalent amongst the less fortunate, the disadvantaged and the uneducated. In the UK, it is no different. Hiscock, Bauld, Amos & Platt (2012) found that smoking rates were four times higher amongst the disadvantaged versus the more affluent (60.7% versus 15.3% - the factors that determined disadvantage included unemployment, income, housing tenure, car availability, lone parenting and an index of multiple deprivation). Fone, Farewell, White, Lyons & Dunstan (2013) found that “respondents in the most deprived neighbourhoods were more likely to binge drink than in the least deprived (adjusted estimates: 17.5% versus 10.6%...)”. Clearly, the incidence of these taxes falls disproportionately on the disadvantaged.

People often smoke and drink for pleasure; this means that these taxes stifle those with fewer resources from attaining pleasure. Conversely, affluent people generally have less trouble substituting consumption goods or in quitting substance use altogether. This prevention of stress alleviation and pleasure attainment will be reflected in sub-potential labour productivity.

The Biopsychosocial model of health suggests that any biological health benefits could be offset by the emotional and financial strain that these taxes induce. The situation is worse for those who are both addicted and poor since they substitute consumption even less than their poor, non-addicted counterparts (thereby reducing their consumption of other important goods). This simultaneously deprives their dependents (quite often children).

A primary concern is that the increase in smoking and drinking will cause several negative externalities (especially in the form of increased healthcare costs). One should consider that, if a drinker or a smoker is aware of the threat of liver failure or lung cancer and yet they choose to ignore it, it is ultimately their choice, their body and their health. A certain degree of respect must be afforded to choice especially since we cannot fully empathise with others.

However, one’s disregard for one’s own health often incurs costs for taxpayers whilst, personally, there are negligible financial costs. In this sense, many may feel disinclined to take care of their health as they might have if treatments weren’t free. So whilst the NHS is still around in its current form, it makes (some, albeit limited) sense to heavily tax alcohol and tobacco. Alternatively, a healthcare system that is at least partially privatised (e.g healthcare vouchers) would enable lower taxation of the disadvantaged and impoverished.