A rousing defence of private property in The Guardian of all places

This is all rather Dr. Johnson in a way, as with seeing a woman preacher. It's that thing with a dog walking on its hind legs: not to see the thing being done so well but to see it being done at all. So it is with Aditya Chakrabortty and his tale of how some council house tenants in East London are being railroaded.

What is powerlessness? Try this for a definition: you stand to lose the home where you’ve lived for more than 20 years and raised two boys. And all your neighbours stand to lose theirs. None of you have any say in the matter. Play whatever card you like – loud protest, sound reason, an artillery of facts – you can’t change what will happen to your own lives.Imagine that, and you have some idea of what Sonia Mckenzie is going through. In one of the most powerful societies in human history – armed to the teeth and richer than ever before – she apparently counts for nothing. No one will listen to her, or the 230-odd neighbouring households who face being wrenched from their families and friends. All their arguments are swallowed up by silence. And the only reason I can come up with for why that might be is that they’ve committed the cardinal sin of being poor in a rich city.

It's as if the assembled plutocrats of the planet are descending to feast upon the bones of good honest working class Brits, isn't it? So, who are the villains here?

Sonia lives in one of the most famous landmarks in east London. The Fred Wigg and John Walsh towers are the first things you see getting off the train at Leytonstone High Road station; they hulk over every conversation on the surrounding streets and the football matches on Wanstead Flats. Since completion in the 1960s, they’ve provided affordable council homes with secure tenancies to thousands of families. Named after two local councillors, they are a testament in bricks and mortar to a time when the public sector felt more of a responsibility to the people it was meant to protect, and exercised it too.

And so they must go. Last month, Waltham Forest council agreed on a plan to strip back the two high-rises to their concrete shells, rebuild the flats, and in effect flog off one of the towers to the private sector. In between Fred and John, it will put up a third block.

Difficult to think of a more rousing argument in favour of private property and against council housing really, isn't it? If you owned the home you lived in, or if the tenants collectively owned the building (as is common enough in buildings of flats) then they, the people who lived in that housing, would be able to control what happened to that housing.

Given that they don't, that it is owned by the local council, they have no such rights. They are subject to the whims of whatever turnips in red rosettes the local Labour Party put up for election. This isn't an argument in favour of "democratic control" of housing or anything else, is it? It is however a very strong argument in favour of private ownership, that private ownership which protects property from such "democratic control".

Chakrabortty doesn't quite manage to spot that logical conclusion to his argument, so we cannot say that he's done it well. But it is still interesting to see this argument in The Guardian, as with the dog on two legs.

The dark threat of the Snooper's Charter

Just hours after marching alongside world leaders in Paris in the name of liberté, David Cameron backed the revival of the Snooper’s Charter in terms little short of terrifying. Free speech, it now seems, is only acceptable only when it can be accessed and reviewed by the state. Speaking to ITV, Cameron said:

…ever since we faced these terrorist threats it has always been possible, in extremis, with the signature of a warrant from the home secretary, to intercept your communications, my communications, or anyone else, if there is a threat of terrorism. That is applied whether you are sending a letter, whether you are making a phone call, whether you are using a mobile phone, or whether you are using the internet. I think we cannot allow modern forms of communication to be exempt from the ability, in extremis, with a warrant signed by the home secretary, to be exempt from being listened to.

The Independent claims that restricting communication to interceptable channels would not just hit typically ‘nefarious’ spaces like the dark web, but any service that encrypts user’s data in a way which shields it from security services. This could include billion-dollar chat service WhatsApp, along with others like Snapchat and Apple's iMessage. Such companies would have to acquiesce to government requests for data and re-writing their software if required, or risk outlaw and the persecution of their users.

This would not be the first time that a government surveillance programme closed down commercial ventures. In 2013 Edward Snowden’s email provider of choice Lavabit chose to close its doors rather than be forced to install surveillance equipment on their network and hand over private encryption keys to the US Government. Silent Circle suspended their email service shortly after.

It’s difficult to predict the impact to the UK’s digital economy should Cameron press on in this vein. Compromising on privacy is something which WhatsApp in particular is unlikely to do. In November, it switched on end-to-end encryption for Android devices, with plans to extend this all 600m+ of its users. Growing up in communist Ukraine, for co-founder Jan Koum user’s privacy is not just a feature, but a defining characteristic of the product:

I grew up in a society where everything you did was eavesdropped on, recorded, snitched on….Nobody should have the right to eavesdrop, or you become a totalitarian state -- the kind of state I escaped as a kid to come to this country where you have democracy and freedom of speech. Our goal is to protect it.

Cameron’s newly- resurrected charter not only challenges a service used by hundreds of millions across the globe, but stands as a barrier to the very value of free expression western politicians profess to uphold. It is more than just a tool to listen in on ‘the bad guys’. And it doesn’t just affect the criminals and extremists, for it strikes right at the heart of our digital infrastructure and dictates exactly what channels of (monitored) communication British citizens are permitted to use to exercise our apparently hallowed right to free speech.

However, whilst the world’s typical, centralized communication industries are at risk from the government’s surveillance fetish, new forms of decentralized, distributed software and communication channels – which have no centralized store of user information or cryptographic keys to raid– would be near impossible to bring to heel.

As ASI Fellow and COO of Eris Industries Preston Byrne explains:

David Cameron has said he wants to 'modernise' the law. I think he fails to understand just how out of date his worldview is. The only way you can shut down encrypted distributed networks today is to either arrest every person running a node and ensure that the data store containing a copy of that database is destroyed, or shut down the internet. Curtailing free association and private communications in the manner proposed is a battle the government is going to lose.

Banning end-to-end encryption will do nothing to prevent the technology from falling into the wrong hands - as any encryption technology worth a damn is open-source, and freely available to all - but will do a great deal to criminalise entirely reasonable measures taken by ordinary people to protect what private lives they have left.

To hang the case for a significantly reduced private sphere off the back of last week’s attacks is opportunistic, unpleasant, and distasteful. The tragedy in France has far more to do with issues of free speech, toleration and extremism than national security. The perpetrators of the French attacks were already known to intelligence officials, as was also the case in the 7/7 bombings and Lee Rigby’s murder. Hardly any acts of terrorism are by relative unknowns, who might have been identified were surveillance laws just that bit wider-ranging. Granting further powers and bigger budgets to security forces might show how ‘serious’ we are that ‘something must be done’, but arguably let agencies off the hook in terms of actually following up on already acquired intelligence.

No doubt Cameron has underestimated the scale, if not the significance, of what he proclaimed yesterday, and his attempt to create a surveillance-friendly communications ecosystem will be futile. But his words represent a threat in many ways much larger and darker than the terror he pledges to protect us from.

Farmers are milking it through state subsidies

Milk is now cheaper than bottled water in some UK supermarkets. So of course there is much wailing that our dairy industry is in terminal trouble and needs subsidy and protection from foreign imports. Wrong. One reason why milk is so cheap right now is that supermarkets are using it as a loss leader. They hope that while customers are buying cheap milk, they might be tempted by less cheap other stuff. They are not actually paying farmers any less.

The dairy industry is indeed in a sorry state, but not because of the lack of state support. Rather, the problem is too much of it. When you protect industries from foreign competition through tariffs (as EU countries like the UK do), and then go on to subsidise them, you kill off competition, both international and domestic. Subsidies and protections allow production to carry on in old, outdated, inefficient, expensive ways. The result is higher prices, lower quality and less choice for customers.

Cold, rainy Britain is not a good place to raise cattle. It's fine in the summer, but in the winter the cattle have to be brought into shelters and given heat, silage and hay, all of which adds to the cost. So other, warmer countries, inevitably have the competitive edge on us.

Dairy producers can compensate for this a bit by creating much larger farms, which can be sited in the sunnier parts of the country, and where large-scale winter housing can be run much more efficiently than countless small-farm cattle sheds. In large, modern facilities, new technology can be employed, such as dry bedding, using other farm by-products for feed, recycling heat, and recapturing methane. And while we are on the subject of greenhouse gases, how much more energy-efficient is it to collect milk from one 8,000-cow farm than from 100 with 80 cows?

But planning policy, that great UK obstacle to progress, is making it hard to build such facilities – a plan for one in Lincolnshire has recently been scrapped. And the existence of subsidies makes it less urgent for inefficient dairy farmers to leave the business, and for more efficient ones to replace them.

Some people argue that we should subsidise UK agriculture to cut down on 'food miles'. Tosh. 80% of food-related emissions are from production, only 4% from transport. So it is 20 times more important to make efficiencies in production. That means super-farms here, or importing products from countries where the climate is more suitable. We do that with wine, why not with other agricultural products? And in any case, domestic production is an environmental nightmare, what with the fertilisers, pesticides and heating that have to be used. DEFRA figured that the carbon footprint of Spanish-grown tomatoes is probably smaller than that of UK tomatoes grown under glass. Remember too that food is transported, efficiently, in bulk. Most 'food miles' are getting small quantities of the stuff from the supermarket to your fridge, which is not going to change even if it is grown locally.

If we scrapped the subsidies and protections, the market could do its stuff, weeding out inefficient production and diverting investment into something better. That would be good for the industry, good for customers in terms of lower prices, good for taxpayers in terms of lower taxes, and good for the planet.

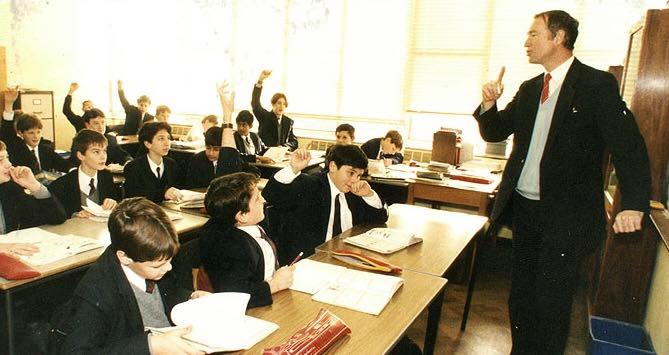

Getting educated - like it's the 21st century

Innovative independent institutions are for those who can afford it and the rest will make do with the stagnant state school system: a status quo forthcoming generations should accept no more. An education revolution is on the horizon and Scotland, following its anticlimactic devolution of education, could lead the change. Solutions to the present state have existed for decades and – if actualised – promise to reinvent the way schooling is viewed for good. The rise of ideas meriting attention must coincide with resolved political leadership to eliminate inertia impeding the education model's evolution.

Shuffling taxpayers’ money back and forth between priorities has left us at a dead-end off the path to progress. Free university tuition fees for the wealthiest in Scotland are funded by taxes from the pockets of school-leavers who have gone straight into the job market. College places - the stepping stone to higher education for many young people - have suffered drastic decline after a sudden culling of courses. The Scottish government now funds free school meals for every child, regardless of need, until Primary 3. Meanwhile the poorest are taxed on almost half their income.

Politicians with the guts to be radical in education are scarce but an alternative to spending more money is necessary. Improving the quality of state schools from the heart of government has failed, and when not completely, has failed to achieve anywhere near the success possible if the public had the freedom to choose their schools. This includes, most importantly, having the pick of the private sector’s offerings. The idea is straightforward: individuals choose the best educational options available to them with their own interests in mind. A demand for the best quality schools that inevitably ensues is met on the supply side by a multiplication of the best schools and practices. The poorest schools and outdated methods become null and void, unwanted, and die out faster.

Placing choice in the hands of those the decision affects generally does not fail to deliver the goods. Products, services and technology once only enjoyed by the wealthy are now widespread and accessible for the common man. But education has not evolved like everything else. So rare are independent schools that most of the existing tiny private sector is branded elitist. And so self-deprecating are we encouraged to react to our great educational institutions that the recurring “Should private schools be banned?” debate is taken seriously and considered the only radical option. One day, these leading independent schools, though it will require us to be radical in the opposite direction, could be accessible to the average person too.

School vouchers is the practical policy in which this school choice could take shape. The voucher would be a means of subsidising the child as the consumer; instead of subsidising the state’s provision as happens now. Accountability and efficiency have so far been lost while politicians spend other people’s money on other people’s education. Each voucher would represent the cost of the state educating the child. Of course there are then many ways the policy can be created to cater to various factors and income backgrounds. First proposed by Milton Friedman all the way back in the 1960s, school vouchers have featured in UK Party manifestos but have never come to fruition here.

The mantra of Scotland's current leadership advocates their goal of a fairer Scotland we are all supposed to be striving towards. These are mere words. True fairness is the enhancing of the freedom to choose on the part of everybody. And as it stands this process is not happening. Implementing choice in policy is absolutely imperative as it will not just be conducive to overall improvement of education but it is a tool to innovate and evolve - the key to advancement.

It takes time to grow a General you know

The latest wafflery on the subject of gender equality is over the in German armed forces.

The Germany army must introduce quotas to boost the number of female officers, the country’s Defence minister said.Ursula von der Leyen said she was embarrassed that the army currently only has one female general.

“She is the only one in the history of the Bundeswehr. This is a lousy proportion. So we have to consider quotas with clear timelines,” she said, to Spiegel magazine.

This is simply nonsense. Other than the medical service and army bands women have only been able to serve in the German military since 2001. So, anyone who did join up as an officer would, possibly, be something around and about a Major by now. For it takes time to grow a General.

Yes, of course, this is just politics, a female politician playing to the gallery. But there's an important point behind it.

There's no doubt that women were discriminated against in the past in certain ways. The same is true of, over different timescales, various religions and ethnicities. But it is not possible to look at society and shout that because we do not have members of those formerly discriminated against groups at the top of society, or an organisation, therefore we must still be discriminating against them. Getting to the top, whether of society or an organisation, is something that takes a lifetime. The question is whether the lower levels of society are discriminating against members of such a group: if not then we've done the reforms that are necessary and will simply have to wait to see careers mature.

For example, the gender pay gap in the UK is in favour of women in the very early years of working life, doesn't really exist until the average age of first childbirth. That is radically different from how the situation was when women now in their 50s first entered the workforce. We can't thus measure the gender pay gap of those women in their 50s as a method of working out whether reform is necessary to produce equality for young women. It is the same with the German army's lack of female generals. Given that women have only been able to be officers for 14 years what does anyone expect? A 34 year old General or something?

Another way to put this is that evidence of discrimination against one generation of people is not, and should not be used as, evidence that there is still discrimination against the next.

Two cheers for Paul Krugman

Paul Krugman says that this (from this Branco Milanovic paper) gives you recent history in one chart, and it's hard to disagree:

Everyone got richer in real terms, although some a lot more than others – and this doesn't fully include technological developments that make pocket supercomputers cheap enough that even people on quite low incomes (for rich countries) can afford them. Like Scott I am more interested in the bottom 80 percent than the top 20 percent, so this is broadly good news. The bottom 10 percent do seem to be left behind to some extent, but African poverty has still fallen by 38% during this period, and most health-related metrics have improved. Maybe issuing more unskilled work visas to poor Africans and Indians would help to boost the incomes of the bottom 10 percent even more.

In another post, Krugman points out that the left's "econoheroes" tend to be of a pretty good academic calibre (he cites himself and Joe Stiglitz, both Nobel Prize winners), whereas the most popular economists on the right tend to be slightly less impressive supply-siders. I think that's fair, and it's a pity. When's the last time you heard a right-wing pundit citing Nobel Prize winner (and not-so-secret free marketeer) Eugene Fama's work on the efficiency of financial markets? Or, indeed, Milton Friedman's monetary prescription for stagnant economies like Japan or, now, the Eurozone?

Well, we try to here at the Adam Smith Institute, and a very honourable mention goes to the excellent James Pethokoukis at the American Enterprise Institute. There are others, but in general I think Krugman's point is pretty fair. For example, I often meet right-wingers who think using monetary policy to generate extra inflation during demand-side recessions is somehow a left-wing idea. This would come as a surprise to Milton Friedman!

I have a theory about why: the post-Cold War consensus has been so good for us – that is, the "Overton Window" of debate has shifted so far rightwards — that the best ideas have been absorbed by the 'centre' and the less compelling ones are all that's left over. That seems unsatisfactory to me, but it does leave me wondering what it means to be a free marketeer, if not a strong preoccupation with the supply side. Maybe Hayek has an answer.

Fiscal austerity might not have hurt growth in the Great Recession

I say 'might', but of course I don't think there's any evidence it did. Anyway, a new NBER paper (gated up to date version, full working paper pdf) from Alberto Alesina, Omar Barbiero, Carlo Favero, Francesco Giavazzi and Matteo Paradisi finds that it did not.

The conventional wisdom is (i) that fiscal austerity was the main culprit for the recessions experienced by many countries, especially in Europe, since 2010 and (ii) that this round of fiscal consolidation was much more costly than past ones.The contribution of this paper is a clarification of the first point and, if not a clear rejection, at least it raises doubts on the second. In order to obtain these results we construct a new detailed "narrative" data set which documents the actual size and composition of the fiscal plans implemented by several countries in the period 2009-2013. Out of sample simulations, that project output growth conditional only upon the fiscal plans implemented since 2009 do reasonably well in predicting the total output fluctuations of the countries in our sample over the years 2010-13 and are also capable of explaining some of the cross-country heterogeneity in this variable.

Fiscal adjustments based upon cuts in spending appear to have been much less costly, in terms of output losses, than those based upon tax increases. The difference between the two types of adjustment is very large. Our results, however, are mute on the question whether the countries we have studied did the right thing implementing fiscal austerity at the time they did, that is 2009-13.

Finally we examine whether this round of fiscal adjustments, which occurred after a financial and banking crisis, has had different effects on the economy compared to earlier fiscal consolidations carried out in "normal" times. When we test this hypothesis we do not reject the null, although in some cases failure to reject is marginal. In other words, we don't find sufficient evidence to claim that the recent rounds of fiscal adjustment, when compared with those occurred before the crisis, have been especially costly for the economy.

The paper comes with a whole load of interesting charts, showing how much newspapers started talking about austerity in 2010, the evolution of Eurozone fiscal policy, the correspondence between different measures of governments' fiscal policy stances, and how much better cutting spending is as a means of belt tightening than raising taxes (contrary to what Keynesian intermediate macro textbooks tell you).

Interestingly, they don't make much mention of monetary policy whether conventional or unconventional. Of course, I believe that fiscal austerity would hurt growth if monetary policymakers weren't willing and able to steady aggregate demand. But so would a particular large firm, for example, reducing investment if this was also coupled with the central bank deciding to cut its nominal target for some reason.

Interestingly, they don't make much mention of monetary policy whether conventional or unconventional. Of course, I believe that fiscal austerity would hurt growth if monetary policymakers weren't willing and able to steady aggregate demand. But so would a particular large firm, for example, reducing investment if this was also coupled with the central bank deciding to cut its nominal target for some reason.

Freedom of speech in a free society

Some people might be deeply shocked by the words, images, arguments and ideas that are sometimes put forward in a free society. But in a free society, we have no right to prevent free speech and block other people’s opinions, even if we all disagree with what is said or find it offensive or immoral. There is certainly a case for curbing language that incites people to violence against others, or that recklessly endangers life and limb – like shouting ‘Fire!’ in a theatre. And there is a case that children need special protection too, which is why we have age classifications on movies and games.

That is very different from preventing particular words, images, arguments and ideas from being aired at all. There can be no such censorship in society of free individuals – for then they would not be free.

There is a practical case for free speech too. People must understand the options available to them if they are to choose rationally and try new ideas – ideas that might well improve everyone’s future. Censorship closes off those choices and thereby denies us progress.

Nor can we trust the censors. Truth and authority are different things. Those in power may have their own reasons–such as self-preservation–to forbid certain ideas being broadcast. But even if the censors have the public’s best interests at heart, they are not infallible. They have no monopoly of wisdom, no special knowledge of what is true and what is not – only debate, argument and experience determines that. And censors may suppress the truth simply by mistake: they can never be sure if they are stifling ideas that will, eventually, prove to be correct. Some ideas may be mostly wrong, and yet contain a measure of truth, which argument can eke out, while the truth of other ideas may become obvious only over time.

The way to ensure that we do not stifle true and useful ideas is to allow all ideas to be aired, confident that their merits or shortcomings will be revealed through debate. That means allowing people to argue their case, even on matters that the majority regard as unquestionable. Truth can only be strengthened by such a contest. It was for this reason that, from 1587 until 1983, the Roman Catholic church appointed a ‘devil’s advocate’ to put the case against a person being nominated for sainthood. It is useful to expose our convictions to questioning. If we believe others are mistaken in their views, those views should be taken on and refuted – not silenced.

From Socrates onward, history is littered with examples of people who have been persecuted for their views. Such persecution often cowers people into staying silent, even though their ideas are subsequently vindicated. Fearing the wrath of the Roman Catholic Church, Nicolaus Copernicus did not publish his revolutionary theory that the planets rotated about the sun until just before his death in 1543. His follower Galileo Galilei was tried by the Inquisition and spent his remaining days under house arrest. Subsequent scientific endeavour and progress in Europe moved to the Protestant north.

Ideas that cannot be challenged rest on a very insecure foundation. They become platitudes rather than meaningful truths. Their acceptance is uncritical. And when new ideas eventually do break through, it is likely to be violently and disruptively.

Certainly, it can be unsettling when people say things with which we fundamentally disagree, express ideas we believe are profoundly wrong, do things we regard as deeply shocking, or even scorn our moral and religious beliefs. And in a free society we are at liberty to disagree with them and to say so publicly. But that is not the same as using the law, or violence, to silence them. Our toleration of other people’s ideas shows our commitment to freedom, and our belief that we make more progress, and discover new truths faster, by allowing different ideas to be debated rather than suppressed.

Adapted from Foundations of a Free Society.

[gview file="http://www.old.adamsmith.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Foundations-of-a-Free-Society.pdf"]

It's terribly difficult to argue that markets are too short term

There's lovely little essay talking about how difficult it is to believe that financial markets are too short term in their outlook. To do so demands that said markets are entirely inefficient in their processing of information. And as this is something that no one but would be commissars still believes then it isn't really possible to insist that markets are short term in their outlook. Here's a part of said essay:

Basically, if capital markets price things well (with few ex ante errors, or put differently, the market is close to “efficient”) then maximizing shareholder value is a very good idea. Believing that markets make common and giant predictable errors is the only legitimate beef one can have with maximizing shareholder value, and it’s absolutely fair to debate this tenet.

But instead of confining the debate to this central point, or even realizing that this is the central point, critics attack shareholder value for many ancillary reasons. For instance, they laugh off the concept as vacuous, the absence of a strategy. They attack share‑based and particularly options‑based compensation. They attack markets and managers for being too “short-term."

The obvious point is that if markets are anywhere near efficient (and just about everybody agrees with the weak version and some more with the semi-strong) in the processing of information then the current market valuation is the value of that company from now into the indefinite future. And, given that we are measuring that flow of funds from that company off into that indefinite future then how on earth can this be short term thinking?

Sure, if you are a would be commissar then you can argue that markets aren't efficient at processing information. At which point you're going to have to explain the difference in food supply in London in 1990 and in Moscow in 1990. When that famous question got asked, "Who is in charge of the bread supply for London?".

Quite, markets are, observably, somewhat efficient at processing information. Thus they are forward looking and as such cannot possibly be short term. QED.

So how does this work then?

It would appear that someone, somewhere, is confused. It could be us that is confused but we're a bit, umm, confused about that. For the claim is that if retailers are providing a subsidy to the consumption of milk then this could devastate the milk producing industry. Which is confusing:

The price of milk has fallen to just 22p a pint thanks to a fierce war between supermarkets. Farmers have warned the UK dairy industry faces extinction if retailers continue to drive down the price – now at its lowest level in seven years. Asda, Aldi, Lidl and Iceland are selling four pints of milk for just 89p, while Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Waitrose are not far behind at £1. Pint for pint, milk is now cheaper than mineral water in most supermarkets. Retailers insist they are funding the cost of the price reduction from their own profits, rather than paying farmers less. Many supermarkets have guaranteed the price farms receive will stay above the cost of production. But farmers say the price war is also devaluing milk as a product at a time when they are under unprecedented pressure.

It doesn't get any less confusing on consideration, does it? The retail price of milk is lower, given the supermarket subsidy to it, leading to higher consumption, while the producer price is "guaranteed" to be above production costs. And this is going to devastate the industry? We don't think it is us getting confused here. Of course, the real background to this is that, as has been happening for the past couple of centuries as farming techniques improve, milk has been getting cheaper and cheaper to produce. And as has been happening over that time the higher cost producers have been pushed out of the market by the lower cost ones. This is, after all, the universe's way of telling you to go do something else, when the price of what you produce is lower than the cost of producing it. That's what is devastating farming, we're in general becoming more efficient at it. And the supermarkets are, through their subsidy, restricting this process which is the very opposite of devastation, isn't it?