President Obama: the ultimate poverty hypocrite

Americans are experiencing buyer's remorse. Last summer CNN found that 53% of those polled would choose Mitt Romney to be president today, over the 44% who chose Barack Obama. And with Obama’s approval ratings fixed these days below 50%, I suppose it’s only human to get a bit testy with those you're compared to:

President Obama poked fun at former rival Mitt Romney and leading Republicans on Thursday, saying the GOP’s rhetoric on the economy was “starting to sound pretty Democratic.”At the House Democratic Caucus retreat in Philadelphia, Obama noted that a "former Republican presidential candidate" was “suddenly, deeply concerned about poverty.”

“That's great! Let's go do something about it!” Obama added in a not-so-veiled jab at Romney.

What’s not particularly smart, however, is to frivolously attack someone’s track record on poverty when your own record looks abysmal:

A few ugly facts about the Obama Presidency:

- Median household income has slumped from $53,285 in 2009 to $51,017 in 2012 just up to $51,939 in 2013.

- In comparison to his three previous successors, this fall in median income looks even worse:

- Real median household income was 8.0% lower in 2013 than in 2007.

- Nearly 5.5 million more Americans have fallen into poverty since Obama took office.

- Obama oversaw the first time the poverty rate remained at or above 15% three years running since 1965.

- Home ownership fell from 67.3% in Q1 2009 to 64.8% in Q1 2014; black home ownership dropped from 46.1% to 43.3%.

- Labour force participation rate fell from 65.7% in January 2009 to 62.7% in December 2014.

- The federal debt owed to the public has more than doubled under Obama, rising by 103 percent.

- 13 million Americans have been added to the food stamp roll since Obama took office.

Obama has been very successful in painting a picture of himself and the Democrats as the 'Party of the Poor', and did an even more sensational job convincing 2012 voters that Romney's riches and successes put him out of touch with the middle-class America. But in reality, the president's policies have pushed millions more people into financial stress and poverty.

And he's still causing damage; even his latest State of the Union address called to raise taxes on university savings accounts and still cited fake unemployment numbers, as if this somehow helps the double-digit workers who have given up looking for jobs.

Perhaps the president really thinks his increased federal spending will pay off for the poor. Maybe he really believes that multi-millions more on food stamps is a saving grace instead of a tragedy. But regardless of intention, the facts speak for themselves.

Obama's talk on poverty is cheap. And his mockery of Romney cheaper.

A new ASI project: book reviews

One can never read too little of bad, or too much of good, books: bad books are intellectual poison; they destroy the mind.

~ Arthur Schopenhauer

The Adam Smith Institute is on the look out for young liberal thinkers to review political, philosophical and economic books! If you are a student and would like to review an important new book-length contribution to the humanities, get in touch.

After we've sent you the book, express your critique in 1000 words and submit it to sophie@old.adamsmith.org to be a part of a new ASI reviews publication we are launching.

We welcome reviews on recent works tackling everything from private schools for the poor to the causes of social mobility, to be edited and compiled together by the ASI research team.

Here are some books we think would be good choices—we are very open to any other suggestions:

- Superintelligence by Nick Bostrom

- Zero to One by Peter Thiel

- The Son also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility by Gregory Clark

- British Economic Growth, 1270 - 1870 by Stephen Broadberry, Bruce Campbell, Alexander Klein, Maark Overton and Bas van

- The Frackers: The Outrageous Inside Story of the New Energy Revolution by Gregory Zuckerman

- The English and Their History by Robert Tombs

- Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Dragon by Yong Zhao

- The Iron Cage of Liberalism by Daniel Ritter

- When the Facts Change: Essays 1995 - 2010 by Tony Judt

- Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy, 1453 to the Present: A History of the Continent Since 1500 by Brendan Simms

- Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood and the Prison of Belief by Lawrence Wright

- If A then B: How the World Discovered Logic by Michael Shenefelt

- The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew Mcafee

- Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race, and Human History by Nicholas Wade

- A World Restored: Matternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace, 1812-22 by Henry a. Kissinger

- The Tyranny of Experts: Economists, Dictators and the Forgotten Rights of the Poor by William Easterly

Logical Fallacies: 5. Equivocation

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x_8xKrKw19M

Madsen Pirie's series on logical fallacies continues with a look at equivocation.

You can pre-order the new edition of Dr. Madsen Pirie's How to Win Every Argument here

Reading Owen Jones at the moment is really rather amusing

His basic contention seems to be that Syriza's election victory in Greece is a rerun of the fight against the Nazis and this time the left must win. Very slightly overblown that comparison.

Syriza’s posters declared: “Hope is coming”. Its election must represent that everywhere, including in Britain, where YouGov polling reveals huge popularity for a stance against austerity and the power of big business. A game of high stakes indeed: one that, if lost, will mean countless more years of economic nightmare.This rerun of the 1930s can be ended – this time by the democratic left, rather than by the fascist and the genocidal right. The era of Merkel and the machine men can be ended – but it is up to all of us to act, and to act quickly.

Quite what style he would use to discuss anything actually important is difficult to imagine.

He has, of course, also got the economics of this entirely wrong. Greece's problems do not really stem from "austerity". They stem from membership of the euro. The harrowing internal deflation the country has been undergoing are the result of their not being able to conduct a devaluation of the currency. And far from it being us "neoliberals" arguing that such deflation is necessary we've all been shouting that the devaluation would have been a better idea. Indeed, the absolutely standard IMF (for which read, in Jones' language, neoliberal, Washington Consensus, right wing etc etc) solution to Greece's problems would have been a loan package, some modest budget constraints and a devaluation.

It's not going to work out well, of course it isn't. Partly because it's difficult to see who is going to win that argument over the debt and partly because the actual domestic economic policies of Syriza are so barkingly mad. But before Britain's leftists start cheering this victory over the forces of reaction they'd do well to understand exactly what we all have been saying these years. If the standard, orthodox, economic policies had been followed the Greek situation would never have arisen in the first place. Sure, they borrowed too much, that happens quite a lot. But the deflation would have been replaced by that devaluation and it would all just be a dim memory by now.

Anti-slavery laws don't help many sex workers, and may end up harming them

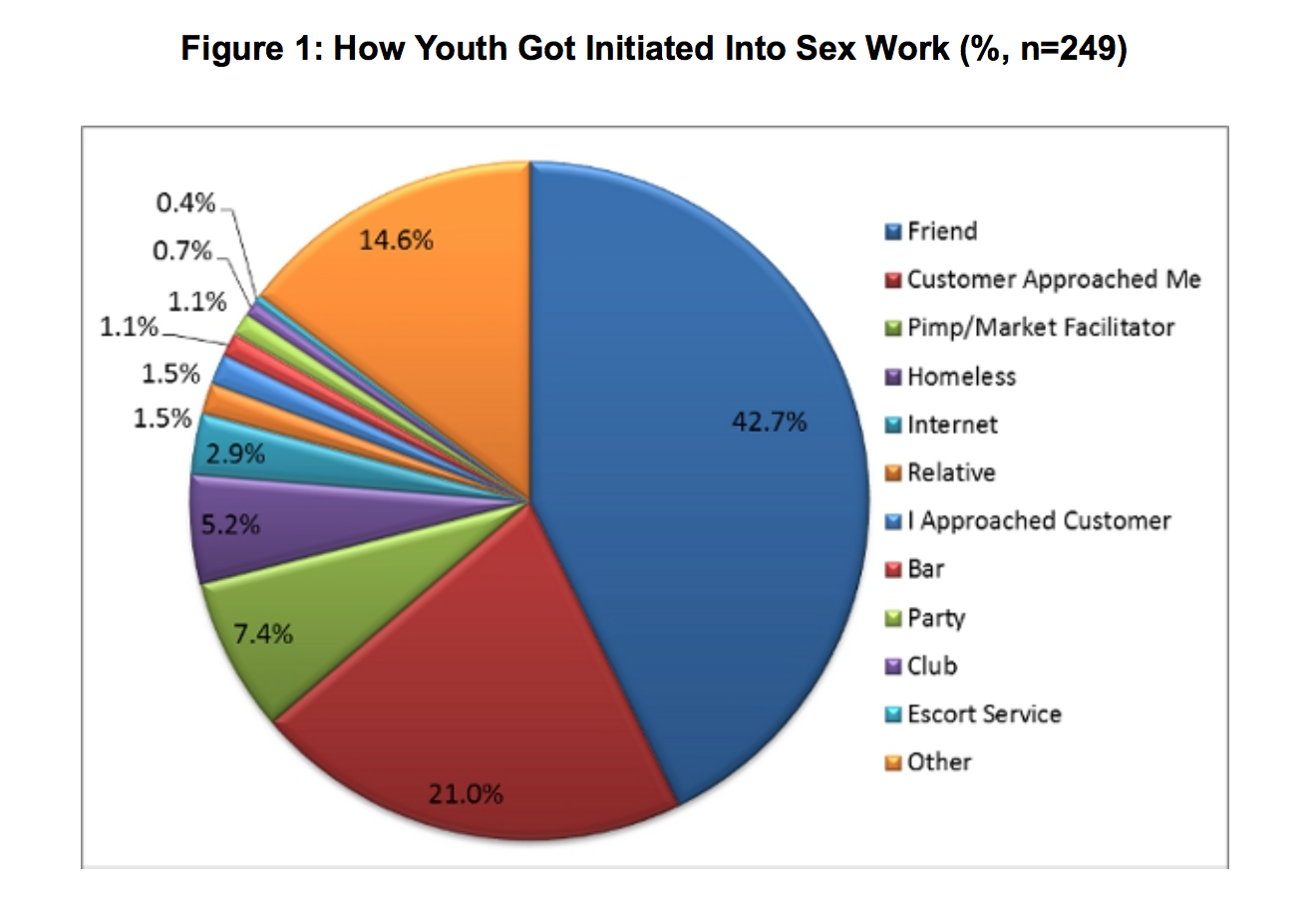

Some people blame sex slavery, or trafficking, driven by pimps for keeping young girls in prostitution. Young girls are drawn in and brutalised by pimps, the conventional wisdom goes, and tackling this is the best way to reduce the number of girls trapped in prostitution. The Modern Slavery Bill in the UK is motivated by this kind of assumption. A new study of underaged sex workers in New York City and Atlantic City seems to suggest that this is actually very rare. Using the largest data set ever gathered in this kind of work in the US, researchers surveyed pimps and sex workers to find out how common pimping was. Figures 1 and 2 below show how few underaged girls are introduced to sex work by pimps and how few actually have pimps on an ongoing basis:

In fact, poverty and lack of access to work, housing or education seem to be what keep girls in prostitution:

None of this tells us that anti-slavery legislation is bad, but it does seem to miss the point somewhat. However, one fact cited by the authors does mean we should think twice about anti-slavery laws: only 2 percent of underaged sex workers said that they would go to a 'service organisation' if they were in trouble, because 'the anti-trafficking discourses and practices they would encounter in these organizations threaten to criminalize their adult support networks, imprison friends and loved ones, prevent them from earning a living, and return them to the dependencies of childhood.'

If only a small number of sex workers count as being trafficked, and anti-trafficking laws alienate others from the services set up to protect them, then anti-slavery legislation may end up having very perverse consequences indeed.

Markets vs. Mandate: the American energy dilemma

New York State’s fracking ban has evoked strong polarising sentiment. Local anti-fracking supporters welcomed the ban as a necessary intervention against corporations pursuing profits at the expense of local safety. The fracking industry on the other hand, saw it as a political move; an example of political interference in the markets at the expense of jobs, energy security and the principles of enterprise and free markets that America stands for. This dynamic is symptomatic of a bigger tension between markets and mandate within the US energy industry; one that that lies at the heart of hotly contested issues like the Keystone pipeline and the proposed TTIP EU-US free trade agreement.

And against the backdrop of a President carving out climate action as a top priority, historic US commitments to reducing emissions, a Republican House majority that views Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency as big-government interventionism, and America’s emergence as a global energy producer, how this tension is resolved affects not just the future of American energy, but has wider global ramifications.

Six years ago I wrote in the Financial Times about the need for less interference in European energy markets to enhance competitiveness; a perspective I still find myself inclined towards today, and for good reason.

Take energy security for example. Shifting responsibility for energy security from suppliers to government would reduce, not increase, security. A liberalised market provides strong incentives for producers to diversify supply and respond to consumer demand. OPEC’s current oil price war might even eventually strengthen a fracking industry forced to become more technically innovative and cost efficient to survive, despite the shorter-term challenges.

Then there is the danger of vested interests influencing a wide government mandate and effectively using government as a proxy for their own interests as illustrated by recent alleged links between energy company Devon Energy and Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt.

And of course there is the notion that climate change justifies state intervention to make cleaner renewables more competitive against oil and gas. But while this is a logical argument, its worth noting that government intervention is at least partly to blame for renewables having less market share in the first place. Federal research for US oil and gas as well as tax credits and subsidies totalling $10 billion between 1980 and 2002 dwarfed state support for renewables, ensuring there was never a level playing field to begin with. And modern-day fracking could not have developed without federal research and demonstration efforts in the 1960s and ’70s.

But as valid as all this is, it fails to tell the whole story.

What makes the energy industry unfortunately unique is the speed with which it could environmentally impact our planet; a factor so exceptional it justifies exceptional action in addressing it, including, if need be, some level of market intervention.

The real problem with the US energy debate is its deep ideological polarisation. Energy discourse is too often pulled towards dogmatic extremes; between those who believe strong government intervention is necessary to further centralise and regulate energy markets, sometimes to the point of protectionism, or conversely those who, as economist Paul Krugman put it when describing the GOP, “believe climate change is a hoax concocted by liberal scientists to justify Big Government, who refuse to acknowledge that government intervention to correct market failures can ever be justified”.

A healthy balance is probably somewhere in-between with sound market based interventions that do not plan energy markets or pick winners through polices like the ethanol blending mandate, but instead couple responsibility for environmental damage and carbon emissions with individual companies and consumers. A carbon tax could help achieve this by using market incentives to strengthen cleaner energies and encourage efficient consumption. After all, why should the burden of carbon emissions, which have a cost, not be factored into a transaction?

And just as timely market adjustments within the financial sector could have averted the worst of the 2008 financial crash and subsequent government bailouts, a carbon tax today would prevent a more drastic future government response to disasters that rising CO2 emissions would undoubtedly cause if left unchecked.

Yet with the looming 2016 Presidential elections, the potential for politicised narratives and populist slogans to take priority over any meaningful measured balance in the US energy discourse is all too real and present.

Somewhere between climate deniers, including prominent GOP members, refusing to acknowledge the need for any climate action, and those attempting to address the problem in a vacuum without considering how sweeping interventionist solutions undermine economic competitiveness (an approach that creates an inevitable political, business and electoral backlash), lie more sustainable, effective solutions. It is vital moderates across the political aisle work together to reach them.

Vicente Lopez Ibor Mayor is currently Chairman of one of Europe’s largest solar energy companies – Lightsource Ltd. He is former General Secretary of Spain’s National Energy Commission between 1995-1999 and was previously a member of the Organizing Committee of the World Solar Summit and Special Advisor of the Energy Program of UNESCO (1989-1994).

Unproductive patents

Patents are a state-granted property rights, designed to promote innovation and the transfer of knowledge. They grant the holder a time-limited, exclusive right to make, use and sell the patented work, in exchange for the public disclosure of the invention. This, so the theory goes, allows creators to utilise and commercially exploit their invention, whilst disclosing its technical details allows for the effective public dissemination of knowledge. However, complaints that the patent system is broken and fails to deliver are common.

Patent Assertion Entities (or ‘Patent Trolls’) buy up patents simply to threaten accused infringers with (often dubious) lawsuits, and are estimated to cost American consumers alone $29bn annually. Another scourge are the 'patent thickets' made up of overlapping intellectual property rights which companies must 'hack' through in order to commercialize new technology. These have been found to impede competition and create barriers to entry, particularly in technological sectors.

Even thickets and trolls aside, using the patent system can carry high transaction costs and legal risks. Litan and Singer argue that this prevents many small and medium businesses from utilizing the system, with over 95% of current US patents unlicensed and failing to be put to productive use. This represents a huge amount of potentially useful 'dead' capital, which is effectively locked up until a patent's expiry.

There are plenty of ways we can tinker with the patent system to make it more robust and less expensive. However, they all assume that patents do actually foster innovation, and are societally beneficial tool.

A number argue that even on a theoretical level this is false; the control rights a patent grant actually hamper innovation instead of promoting it. Patents create an artificial monopoly, which results, as with other monopolies, in higher prices, the misallocation of resources, and welfare loss. Economists Boldrin and Levine advocate the abolition of patents entirely on grounds the that there is no empirical evidence that they increase innovation and productivity, and in fact have negative effects on innovation and growth.

A new paper by Laboratoire d'Economie Appliquee de Grenoble, authored by Brueggemann, Crosetto, Meub and Bizer backs this claim, by offering experimental evidence that patents harm follow-on innovation.

Test subjects were given a Scrabble-like word creation task. Players could either make three-letter words from tiles they had purchased, or extend existing words one letter at the time. Those who extended a word were rewarded with the full 'value' of that word, creating a higher payoff to sequential innovation. In ‘no-IP’ (Intellectual Property) game groups, words created were available to all at no cost. In the IP game groups, players could charge others a license fee for access to their words.

The results are striking:

We find intellectual property to have an adverse effect on welfare as innovations become less frequent and less sophisticated…Introducing intellectual property results in more basic innovations and subjects fail to exploit the most valuable sequential innovation paths. Subjects act more self-reliant and non-optimally in order to avoid paying license fees. Our results suggest that granting intellectual property rights hinders innovations, especially for sectors characterized by a strong sequentiality in innovation processes.

In fact, the presence of a license fee within the game reduced total welfare by 20-30%, as a result of less sophisticated innovation. Players in these games used shorter, less valuable words, and in order to avoid paying license fees would miss innovation opportunities which were seized upon in no-IP games.

The authors suggest that patents could be harmful in all highly sequential industries. These range from bioengineering to software, where the use of patents has been strongly criticized, through to pharmaceuticals, where the use of patents is much more widely accepted. If patents really do restrict follow-on innovation even remotely near as much as suggested, the implications could be huge.

Of course, the study is only experimental and far less complex than real life, but it’s a useful contribution to the claim that patents do more to hinder than to help.

You should be very careful what you wish for

An interesting little observation from Ed Lazear:

There are basically two ways that the average economywide wage can fall. There might be a shift in employment away from high-paying to lower-paying industries; in other words, the economy is producing more “bad jobs.” The other way is that the overall composition of work might be the same, but wages for the typical job in most sectors have fallen.

Normally, economywide wage changes reflect what happens to the wage of the typical job. But between 2010 and 2014 there were also significant declines in the proportion of the workforce employed in two high-paying industries. Those declines contributed to overall wage declines—and they may have been caused by policy mistakes.

The share of the private workforce employed in the BLS-defined industries “financial activities” and “hospitals” decreased by about 5% between 2010 and 2014. Jobs in these industries pay 29% and 24%, respectively, above the economy mean. Because a smaller share of labor is working those high-wage industries, the typical job in the economy is now lower-paying than in 2010.

What has been happening here in the UK?

Well, our highest paying industry by a long way is wholesale finance, The City. And for several years that industry was shrinking. And average wages were declining. The City is now expanding again and average wages are rising. It would not do to insist that all of both the rise and fall depends upon the hiring practices of The City. But certainly some of it does.

Which leaves us in a state of some amusement. For of course it is those who have been whingeing most about the domination of the financial markets who have been complaining loudest about the fall in wages. Be careful what you wish for for you might well get it.

Tough on the causes of crime

Let's be very reductionist and say that the prevalence of crime is affected by people's biology, their upbringings, social environment and finally the crime and punishment system. In many ways the hardest things to change are their biology, so let's just ignore these for the time being (although see 1 2). Then what we have are upbringings/society and the crime and punishment system. Being very broad brushed we could say that before 1800 people put little faith in the former and lots in the latter. Nowadays people tend to be split between whether they place their faith in being tough on crime or tough on the causes of crime (can't resist dropping this link here).

I favour both approaches, but outside of the fact that being just selected into a better school makes you a bit less likely to commit crimes, most social interventions we know don't seem to have much effect. It might be a dead end. Start with the fact that 65% of UK boys with a father in prison will go on to offend. That's easy to understand on the social-upbringing account: these people probably lack nurturing environments, live in bad neighbourhoods and so on.

The problem is that these just-so explanations don't seem to fit the data.

- Parenting: here's a 2015 US paper showing "very little evidence of parental socialization effects on criminal behavior before controlling for genetic confounding and no evidence of parental socialization effects on criminal involvement after controlling for genetic confounding".

- Family income: here's a 2014 Swedish paper showing "here were no associations between childhood family income and subsequent violent criminality and substance misuse once we had adjusted for unobserved familial risk factors".

- Bad neighbourhood: here's a 2013 Swedish paper finding "the adverse effect of neighbourhood deprivation on adolescent violent criminality and substance misuse in Sweden was not consistent with a causal inference. Instead, our findings highlight the need to control for familial confounding in multilevel studies of criminality and substance misuse". (In fact, this weird 2015 US paper found that low-income boys surrounded by affluent neighbours committed more crimes).

I realise there are other studies saying different things—I don't want to sci-jack or be the Man of One Study—but many of these use caveman methodologies that don't even attempt to account for the potential that some people are born different to others (e.g. some have more testosterone). And I think we can be cautiously confident in these findings because they fit with other things we know.

So we're left with enforcement. Can that make a difference? Today black Americans commit many more crimes per capita than whites, despite committing fewer than them in the late 19th Century. It's possible that the results above are only true for a narrow range of environments, and thus that social-familial affects are driving this.

But in any case do we really think that blacks in today's USA live in worse environments than the blacks of the post-bellum USA? If environments are improving and people are pretty much the same genetically, then the criminal justice system may be the big changing factor.

I think the criminal justice system looks like the area where research could most plausibly lead to improved outcomes. Consider the imposition and enforcement of restrictive drug laws, which coincided with the crime wave, and which may increase violent crime (e.g. by inducting people into the criminal life, or by providing a lucrative trade to fight over).

Some way of changing improper or inadequate enforcement—e.g. liberalising drug laws—may be a can opener to assume but it's nothing like the assuming the can opener of changing genetics or magic social interventions that actually work.

Of all the idiot suggestions

Of the idiot policies that politicians have tried to bake over the years this one rather takes the cake:

Scottish Labour MP Thomas Docherty is calling for a national debate on whether the sale of Adolf Hitler’s “repulsive” manifesto Mein Kampf should be prohibited in the UK.Docherty has written to culture secretary Sajid Javid about the text, pointing out that it is currently “rated as an Amazon bestseller” and asking the cabinet member to consider leading a debate on the issue. An edition of Mein Kampf is currently in fifth place on Amazon’s “history of Germany” chart, in fourth place in its “history references” chart, and in 665th place overall.

“Of course Amazon – and indeed any other bookseller – is doing nothing wrong in selling the book. However, I think that there is a compelling case for a national debate on whether there should be limits on the freedom of expression,” writes Docherty to Javid.

Excellent, let us have that debate.

The answer is no.

On the simple grounds that freedom of speech really does mean what it says. People, even dead people, are free to spout their opinions however absurd, racist, hateful, jejeune or potentially damaging they may be. They may not libel and they may not incite to violence but within those constraints freedom really does mean freedom.

“This is not a debate around political books or manifestos or books which cause offence … What Mein Kampf and books like it do is specifically set out to incite hatred. It is literally the manifesto for Nazism.”

And that is why this is so important for this specific book. Yes, Hitler really did write down what he was going to do and when he gained power he went and did it. Which is why this specific book must remain available. So that we all remember that people often do have their little plans and it's wise to make sure that certain people don't get to enact them. As with that other little book that contributed so much to the tragedies of the 20 th century. Sometimes those who talk about the elimination of the bourgeoisie as a class really do mean it. Better to be warned and avoid, no?