How to Tie a Bow Tie - An Alternative Method

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RfuGYt5iPjQ

Noted bow tie wearer and President of the Adam Smith Institute Dr. Madsen Pirie is often asked how he manages to tie such neat bow ties. He made this video to demonstrate his alternative knot.

The second edition of Madsen's book on logic, How to Win Every Argument, is available to pre-order here

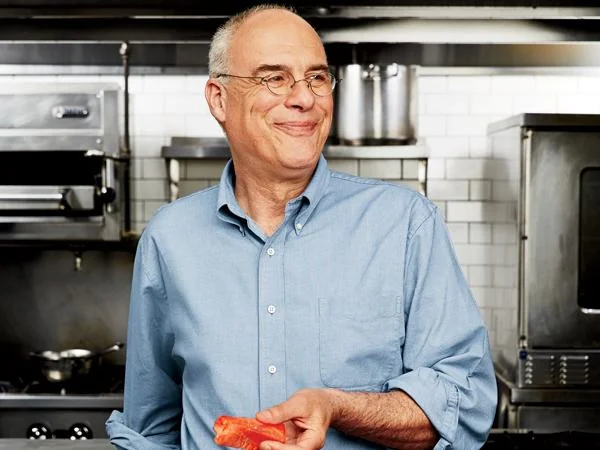

Watch Mark Bittman destroy his own argument

This is really most amusing from Mark Bittman over in the New York Times. For those who haven't heard of him he's supposed, really, to be a food writer. But every column seems to come out as a call for a revolution in society. Larded, of course, with references as to how this will make food better so as to justify his niche and position. But his latest column really rather manages to trip over itself:

The world of food and agriculture symbolizes most of what’s gone wrong in the United States. But because food is plentiful for most people, and the damage that conventional agriculture does isn’t readily evident to everyone, it’s important that we look deeper, beyond food, to the structure that underlies most decisions: the political economy.Progressives are not thinking broadly or creatively enough. By failing to pressure Democrats to take strong stands on everything from environmental protection to gun control to income inequality, progressives allow the party to use populist rhetoric while making America safer for business than it is for Americans.

You see what we mean, it's a bit of a leap from conventional agriculture to gun control really. And he ends with that call to revolution:

It’s been adequately demonstrated that more than minor tweaks are needed to improve life for most people. Let’s try to make sense of where the world is now instead of relying on outdated doctrines like “capitalism” and “socialism” created by people who had no idea what the 21st century would look like. Let’s ambitiously and publicly philosophize — as the conservatives do — and think about what shape a sensible political economy might take.

The big ideas and strategies for how we should manage society and thrive with the planet are not a set of rules handed down from on high. To develop them for now and the future is a major challenge, and we — progressives and our allies — have to work harder at it. No one is going to figure it out for us.

Well, there's a certain problem with those big ideas and strategies really. A problem that he himself mentions earlier:

We don’t all agree on goals, and we don’t agree on whether things are working or in need of repair.

So, if we don't agree on the goals then how can we have big ideas and strategies to get to wherever it is that we disagree about? The column's headline is:

What Is the Purpose of Society?

And that's where we really, really disagree. We don't believe that there can possibly be a goal for society. Not one that we all agree upon and then have big ideas and strategies to reach.

Except, of course, that the goal of society is for us all to be able to do whatever it is that we wish to so long as in our doing so we don't damage others' opportunities to do the same. And we're deeply unconvinced that this goal is going to be reached by anyone having big ideas and strategies: unless it's the one where we tell the people with the big ideas and the strategies to get out of our lives and go and do something more interesting with their own.

Enemy of the steak: what's wrong with government diet guidelines

As an amateur chef I have become increasingly interested in the government’s guidelines and regulations around food. For something so central to our lives, the advice and rules the government makes to do with what we eat are usually overlooked. Two developments this week suggest that this is a mistake. I have previously argued that government regulation is often bad because, if it turns out to be bad regulation, it imposes a single error across an entire group of people or firms. That view may explain the financial crisis, where banks were required to hold lots of mortgage debt by regulators who thought they were forcing banks to be sensible.

Now, it looks as if it might also apply to diet guidelines. This week a new paper has been published that argues quite convincingly that, not only does modern evidence show that government guidelines to reduce dietary fat intake were a bad idea, they were even against the bulk of the evidence available at the time.

Today, it’s being reported that the US will stop advising people to avoid dietary cholesterol, because of a change in nutritionists’ view of how our diet affects our bodily cholesterol levels.

The Verge says that ‘The DGAC is more concerned about the chronic under-consumption of good nutrients, noting that Vitamin D, Vitamin E, potassium, calcium, and fiber are under-consumed across the entire US population.’ Interestingly, high-cholesterol foods like eggs, offal and seafood are very high in some of those vitamins.

It’s tempting to suggest a connection there – that vitamin deficiencies may be a direct cause of misguided government diet advice. And this may be the case. But, having looked around and spoken to the British Nutrition Foundation, I can’t find any work by either the government or independent academics on how much impact these guidelines have on what we eat, let alone on our health. (The exception is the five-a-day campaign, which has been fairly successful.)

If it turns out that diet guidelines have been wrong on things like fat and cholesterol, and maybe things like salt as well, what are the costs? I see there being two potential downsides to bad advice. The first is that the advice is actually dead wrong and drives people to eat in ways that ends up being worse for their health. Perhaps this is true of the cholesterol advice.

The second, which is more ambiguous, is the welfare cost. We eat not just for sustenance but because it gives us pleasure – a steak done well is much better for me than a well-done steak, because, even though the nutritional content is basically the same, it makes me happier. If government guidelines have been mistakenly putting people off eating foods they enjoy then they have been costly in welfare terms even if the health impact is not significant.

Of course people may need to get advice from somewhere, and I don’t see any reason to believe that government advice is worse than, say, the stuff you get in the Femail section of the Mail Online website. But if government diet regulations are still likely to be mistaken, and they influence people much more than any single bit of diet advice from an independent source, then they may end up holding back a process of private trial and error that would give us better information about what’s good to eat over time.

Economic Nonsense: 4. Population growth will involve malnourishment & starvation

Malthus made this mistake. He thought that food supply could only increase arithmetically, whereas population must increase geometrically. He thought the result would always be more people than could be fed, with mass starvation and misery resulting. He was wrong about both the food supply and the population, as are present-day alarmists who speak of the future world "drowning in people" and call for urgent steps to limit population.

Humankind's ability to produce food has increased beyond anything Malthus could have envisaged. Improvements in agriculture, in developing higher yield grains and in better animal husbandry have all enabled more food to be produced per acre. The Green Revolution saw new crop strains combined with better agricultural management produce a huge increase in yields. Genetically modified crops now offer the prospect of crops bred to be drought tolerant, salt-water tolerant, pest resistant and self-fertilizing, and offer a second Green Revolution with not only higher yields per acre, but crops that can prosper on previously infertile land.

Far from increasing out of control, population growth is levelling off. As countries become richer, families do not need as many children to augment the family budget through their work. As people are able to fund social services, they no longer need children to support them when they grow old. The emancipation and education of women has played a significant role in this change. Population growth in rich countries levels off. In most European countries it is now negative, offset in some like the UK only by immigration.

The world's future population, predicted by some to reach 50 billion within a century, now is on course to level off at about 10 billion, and then to decline. The combination of more abundant food and a significant reduction in population growth suggests that the latter-day Malthusians and doomsayers are wrong. Population seems to be levelling off within a limit that modern day technology can provide adequate food for.

More of Will Hutton's whatabouttery

What joy, apparently we're to be treated to another volume of whatabouttery from Will Hutton. Containing such gems as this:

Five million wait to be housed – yet over the last generation, five million council flats have been sold and not replaced.

So? Does Hutton think that council houses are destroyed when they are sold? Or perhaps people actually buy them to live in? Meaning that the existence of one ex-council house means one household that does not require a council house? Well, quite, it's the latter, obviously.

The other of his suggestions that caught our eye was this:

The cornerstone of a new approach to ownership should be a Companies Act for the 21st century. Unlike the existing act, passed in 2006, this would set out unambiguously what society expects from companies in exchange for the privileges they are afforded. The aim is to create purposeful companies with a more just relationship between themselves and the wider society, capable of fostering the trust relationships that are at the heart of high-innovation and high-performance workplaces. Companies would be required to declare their business purpose on incorporation: they should incorporate to deliver particular goods and services that serve a societal or economic need and will need particular capabilities and skills. It is through delivery of their purpose that they should seek to make profits. Most great companies have this purpose at their heart already, even if informally. Unilever famously exists to make the best everyday things for everyday folk – Boeing to build planes that fly furthest safest. This should become the rule, not the exception.

Oh great. We can never remember whether it was Nokia or Ericsson that used to make rubber boots but then switched to mobile phones but this would ban that idea. And Apple moving from computers to smartphones would also be illegal. And this is quite separate from the basic fact that whatever you set up a company to do usually isn't what the company ends up doing. Simply because no business plan ever survives contact with the market.

Hutton's deliberately insisting that we should hobble the flexibility and adaptability of the market system. Said adaptability and flexibility being one of the great points about having a market system in the first place. It fits with his own ideas about how the economy works, this is true. That some small number of the Great and the Good (naturally including one W. Hutton) sit around and plan how the rest of us do everything. But that his actual suggestions are also insane is why we should pay him no heed.

Just to rub the point in, one of the examples of a great company that he uses is Rolls Royce. Which started out to make cars and only later moved into jet engines. A declaration that they only existed to make great cars would have been a bit of a problem for that later development, would it not?

Logical Fallacies: 9. In denial

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0uSCkvRchBw

Madsen Pirie latest video on logical fallacies. This one is called 'In Denial'.

You can pre-order the new edition of Dr. Madsen Pirie's How to Win Every Argument here

Liberty League Freedom Forum 2015

Tickets to this year's Liberty League Freedom Forum are now on sale. Now in its fifth year, LLFF is the UK's largest gathering of the next generation of pro-liberty enthusiasts. 2015's Freedom Forum takes place between Friday 27th - Sunday 29th March, at Guy's Campus, KCL, London.

The weekend will feature seminars with leading academics, activists and professionals, including the ASI's Sam Bowman on What's wrong with social democracy. Other sessions include:

- Introductions to classical liberal, objectivist, anarchist and left-libertarian thought,

- Panels on free-market feminism, current threats to liberty, and digital surveillance,

- Magna Carta: Birth of democracy or historical fantasy?

- Laissez-faire monetary economics, Bioethics, Bitcoin and much, much more.

Practical workshops will cover skills from campaign training to journalism, with evening socials to share many a drink with like-minded attendees.

A ticket to Freedom Forum covers speaker sessions, food, drink, and evening socials, with a limited number of hostel accommodation spaces available. Tickets start at just £25, but book before 8pm tonight (Weds, 11th Feb) to get 25% off the standard price.

Full information about the conference, speakers and the schedule can be found on the LLFF15 website, and on the Liberty League Facebook and Twitter. Liberty League is a network for pro-freedom students and young professionals, but all ages are welcome at Freedom Forum.

Economic Nonsense: 3. There has to be a winner in every bargain

This is not true, and is based on the false zero sum game fallacy. The assumption behind it is that value is fixed, so that if someone gains more of it, someone else will obtain less. People commonly ask who gets the best of a bargain, wrongly assuming that one party gains at the expense of the other. In fact, value is not a fixed property of objects, but something in the mind of those who think about them. People are different and they value things differently; and value is not fixed or in limited supply. When a voluntary exchange takes place it is because each party puts greater value on what the other party has than they put upon what they are ready to trade for it. When the trade takes place, each party acquires something they value more than what they already had. Both gain in value; this is how wealth is created.

It is not a case of one party winning and the other losing. Rather is it a win-win situation in which both parties have added value to their lives.

Just as both usually gain in a voluntary bargain between people, so do both sides usually gain in a freely-entered exchange between nations. People in one country trade what they have in return for what they value more from the other country. Both become wealthier as a result. It is trade and exchange that makes countries wealthier, not trying to accumulate precious metals or plundering wealth from others. When countries abandoned the idea that they could grow rich at the expense of others, the world's wealth began to grow dramatically. Trade has made everyone winners.

These people are mad you know

Sad to have to say it but this is a most startling claim:

Private landlords are benefiting from subsidies worth the equivalent of £1,000 for every household in the UK, the campaign group Generation Rent has claimed, with tax breaks and housing benefit bolstering their gains from house price increases.Figures shared with the Guardian by the group suggest landlords could be gaining as much as £26.7bn a year from the taxpayer, equal to £1,011 each for the country’s 26.4m households.

So, how have they calculated this figure?

The group’s figure is made up of £9.3bn of housing benefit paid on behalf of low-income tenants, £1.69bn through the “wear-and-tear” tax relief landlords can claim on their properties, £6.63bn of tax that landlords do not have to pay on mortgage interest payments and £9.06bn of tax landlords do not pay on their annual average capital gains.

Oh dear. Capital gains, capital gains on anything at all, are only taxed when a transaction takes place. Thus the not taxing of a capital gain when a transaction does not take place is not a tax break. Similarly, the paying of interest for the purchase of a business asset is tax allowable. This is true of buying a JCB for a building firm, buying a house to rent out and buying a mobile phone mast to provide service to said house. This is not a tax break therefore. It's simply a cost of doing business that must be included before calculating the profit which will be taxed. Wear and tear relief is very much the same thing.

Housing benefit is a little more complex. We can indeed view it as a subsidy to landlords. For without housing benefit being paid we might expect rental prices in general to be lower. We might also view it as a subsidy to low income tenants of course. That's what it's intended as. The way to decide between who is getting that subsidy is to ask, well, what would happen to prices in the absence of it? If we think that removing that £9.3 billion subsidy would mean that rents in general would fall by £9.3 billion then it is indeed a subsidy to landlords. If we think that prices would stay largely where they are but that poor people wouldn't have anywhere to live then it's a subsidy to those poor people. And, of course, if it's the first then we should simply abolish that subsidy immediately.

Which is rather the point of that thought exercise: those who claim that it is a subsidy to landlords should be campaigning for the immediate abolishment of that subsidy. They ain't, so they don't really think it is, do they?

Rare disasters and the efficient markets hypothesis

One common strand in financial economics research is that financial markets are not perfectly efficient, i.e. they do not immediately and consistently incorporate all facts about the world in prices. I have several feeds set up for new papers in the area and at least five new papers come out each week finding that while markets are far more efficient than random, there are a number of departures from perfect efficiency.

I had always wondered why this was true: surely if there really are all these easily-exploitable bets then there would be at least some market participants who would exploit the hell out of them. Markets do not come to rest at the median view of everyone, but the position where no one wants to trade—so it doesn't matter if most people are 'behavioural'.

If the inefficiencies—i.e. prices that differ from fundamental values—cannot be bet on then there's a question of why: if it's down to regulation then that's hardly surprising and doesn't really tell us anything about markets; if it's down to the (non-regulatory) cost of trading then it's not an inefficiency. It's more socially efficient all things considered to not trade on those inefficiencies—i.e. the social benefits of getting to the true price are outweighed by the social costs needed to get there.

Well a new paper seems to give a strong undergirding to my thoughts here. Entitled "Disaster risk and its implications for asset pricing" (pdf) and authored by Jerry Tsai and Jessica Wachter (hat tip to Robin Hanson), it says that most of these inconsistencies are parsimoniously accounted for by the risks of catastrophic disasters like the Great Depression.

These make certain sorts of assets (like stocks) less attractive by dint of the fact there is a very small chance that they might tank a huge amount. Otherwise there seems to be a big puzzle why stocks return so much more than bonds.

After laying dormant for more than two decades, the rare disaster framework has emerged as a leading contender to explain facts about the aggregate market, interest rates, and financial derivatives. In this paper we survey recent models of disaster risk that provide explanations for the equity premium puzzle, the volatility puzzle, return predictability and other features of the aggregate stock market. We show how these models can also explain violations of the expectations hypothesis in bond pricing, and the implied volatility skew in option pricing. We review both modeling techniques and results and consider both endowment and production economies. We show that these models provide a parsimonious and unifying framework for understanding puzzles in asset pricing.

This probably leaves a few market puzzles unexplained—perhaps many—but I expect these may eventually yield simple, plausible and efficiency-preserving explanations. As Eugene Fama points out in a brilliantly clear introduction to and history of the EMH it is very hard to test market efficiency since you must always make assumptions about risk at the same time.