The Lord's Digital Agenda

On Tuesday the House of Lords Select Committee on Digital Skills released the 144-page report ‘Make or Break: The UK’s Digital Future’. It’s a typical government report, calling for ‘immediate and extensive action’ in something or other — and in this case, unifying government's current, disjointed digital initiatives with the launch of a grand ‘Digital Agenda’. (This masterplan includes such fabulous ideas as the middle-aged men in central government ‘future-proofing our young people’ through things like bolting-on a digital element to all apprenticeship schemes.) One of the report’s most newsworthy findings was London’s poor broadband speed, comparative to other European capitals. In a ranking of their average download speed London came 26th — nestled between Warsaw & Minsk —whilst the likes of Bucharest, Paris and Stockholm topped the chart. London also came 38th in a rating of the UK's cities’ speeds (although it's worth noting that Bolton, the UK’s fastest city, would make the European capital ranking’s Top 10). The Lord's report is also concerned with the persistence of internet ‘not spots’ in urban areas, universal internet coverage and the rollout of superfast broadband. In response, it calls on the government to classify the internet as a utility service, with the desirable goal of universal online access.

It goes without saying how vital digital connectivity is to the modern economy, as well as the importance of staying internationally competitive. However, a new, centrally-dictated ‘Digital Agenda’ is probably quite an ineffectual and expensive way of boosting the digital economy.

Despite the House of Lords' fears about the speed of superfast broadband rollout, coverage has increased from 55-60% of the UK in 2013, to 70-75% in 2014. And, whilst the report holds up Cape Town as an example of a city providing universal broadband, this won’t be ready until 2030. In the time it takes for the state to roll out the chosen digital infrastructure, it may already be out of date. Whilst many are still choosing between regular or fibre optic broadband, landline-free 4G home broadband is the latest offering to hit London. At the same time, eyes are already on 5G, and the new capabilities it can bring.

Treating the internet as a public utility is also problematic from a free-market standpoint. Doing so could, for example, lead to calls for more government involvement in the deployment and update of internet infrastructure. However, a study by the Mercatus Centre looked at American municipal government investment in broadband networks across 80 cities, and found that for the billions of dollars of public money spent, there was little community or economic benefit.

It’s also the type of thinking which has led to America's ‘Net Neutrality’ debate, where, on the behest of Obama, the Federal Communications Commission has proposed to regulate internet service providers as 'common carriers', and in doing so, subject the net to a 20th century public utility law originally devised to deal with the telephone monopoly. Ostensibly designed to protect consumers from the creation of ‘anti-competitive’ internet fast lanes for big content producers, Net Neutrality legislation threatens not only the speed, price and quality of internet provision, but the autonomy of ISPs and investment at the core of the net.

Whilst the Lord's proposed 'Digital Agenda' might seem far-removed from such heavy-handed state activity, a government who considers it their duty to take online and 'digitally educate' every single citizen risks heading down an increasingly interventionist and expensive path.

Remarkable what you can learn from bishops these days

The Anglican bishops have decided to tell us all something about how to achieve the good life. Amazing what you can learn from bishops these days really:

Adam Smith, the father of market economics, understood that, without a degree of shared morality which it neither creates nor sustains, the market is not protected against its in-built tendency to generate cartels and monopolies which undermine the principles of the market itself.

No, not really. Smith thought the market would do just fine. But that there will always be attempts to use the law and regulation in order to privilege certain producers into those cartels and monopolies. It was actually Karl Marx who insisted that markets inevitably led to monopolies, Smith who pointed out that not messing with markets with regulation was an aid to preventing monopolies.

But we are also a society of strangers in a more worrying sense. Consumption, rather than production, has come to define us, and individualism has tended to estrange people from one another. So has an excessive emphasis on competition regarded as a sort of social Darwinism. (This is a perverse consequence of allowing market rhetoric to creep into social policy. For an economist, competition is not the opposite of cooperation but of monopoly).

Yet that is extremely perceptive. We might go further (as we do) and argue that competition is actually how you decide to cooperate with, the first being the precursor to the second. The supplier to the steel mill is, after all, cooperating with the steel mill in being a supplier.

One important principle here is the idea of subsidiarity – the principle that decisions should be devolved to the lowest level consistent with effectiveness. Subsidiarity derives from Catholic social teaching, and it is a good principle for challenging the accumulation of power in fewer and fewer hands. It does not mean that everything must be devolved to the most local level. Nor is it about handing small matters downward whilst retaining all meaningful authority in the hands of the powerful.

We would most certainly support that. We might insist that rather more things can and should be done at rather lower levels than some others but we're absolutely fine with the general principle.

As an example, “post code lottery” has become a term of disparagement for local variations in public services. But that implies that a single standard, determined and enforced nationally, is the only way to order every aspect of public life. It is certainly true that many services should be available as equally as possible to every citizen. But it is also true that different communities have different needs and may choose different priorities. If people feel part of the decision-making processes that affect their lives, there is no reason why, in many aspects of social policy, local diversity should not flourish.

Quite, who wants a monolithic drabness to the nation?

The desire for neatness, as much as the desire for control, is characteristic of how politicians tend to think – especially those in government or contemplating office. They are often backed up by bureaucracies which are allergic to messiness. But human life and creativity are inherently messy and rebel against the uniformity that accompanies systemic constraints and universal solutions.

By now we're rather wondering whether there hasn't been a revolution in the Anglican Church. Perhaps an influx of Austrians?

Whether on the political right or the political left, it is a long time since there has been a coherent policy programme which made a virtue of dispersing power and control as widely across the population as possible.

We have been chanting that lonely hymn for some time now.....

This document is much more interesting than the predictable ways that the various newspapers have been covering it. interesting in the sense of being something of a curate's egg: parts of it are excellent.

Economic Nonsense: 9. International agreement on tax rates would benefit everyone

International agreement on tax rates would hurt everyone except those who collect and spend taxes. Governments have little restraint on the degree to which they can take the money earned by their citizens and spend it on overblown projects designed ultimately to buy votes and secure their re-election. They meet some resistance as they increase their tax take, but people can do little except grumble. Very often there is little difference between the major political parties, or between the tax rates they levy while in office, so democratic restraints are minimal. The one effective restraint is the ability of people to move to another jurisdiction. This is especially true of modern economies which place considerable value on the talents of high-achieving individuals. Government is restrained on what it can tax them by their ability to move. When faced with punitive tax rates, they can relocate to somewhere more favourable. High earners in France, and those with aspirations to become so, began to leave the country in significant numbers when faced by government plans to levy a top income tax rate of 75%. Similar effects have been observed elsewhere.

What is true of individuals can be true of companies. They, too, can choose to relocate to areas where tax rates are friendlier. The Republic of Ireland found its low 12.5% rate of corporation tax attracted companies to base themselves within its borders. High rates of corporation tax elsewhere added to Ireland's attraction.

Those who support high taxes dislike this restraint and many of them call for international harmonization of tax rates. The aim of this is to make it pointless to relocate, and to remove the one curb on over-large and over-costly governments. They dislike what they call 'tax competition.' But relatively low taxes on high earners and business constitute a business-friendly environment and are conducive to economic growth. Those who call for harmonization are in effect saying they do not want any countries to be more business-friendly than others. Denied an escape to less oppressive tax regimes, people become the helpless prisoners of rapacious governments.

Logical Fallacies: 11. False precision

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hj5VcIASCDQ

The latest in Madsen Pirie's series on logical fallacies: 'False precision'.

You can pre-order the new edition of Dr. Madsen Pirie's How to Win Every Argument here

Keep Politicians out of the NHS

In the run-up to the election, politicians are trying to out-bribe us with our own money to pay for escalating NHS expectations. Democracy has a dark side. Doctors are telling politicians to: “stop messing with NHS to win votes.” (The Times, 17th February, p.15). Demand will always outstrip capacity for a free good such as health. The questions are simply two: how much money should be allocated to the NHS and how should those resources be best managed to maximise welfare? The former question is essentially political but the latter should not be. The budget should be set annually and not agonised over every day.

As every government IT project demonstrates, government does not do management well. One can blame either politicians or civil servants but it is the combination that is fatal. Apparently the present Secretary of State for Health assembles his entire team every Monday morning to micro-manage NHS issues in Darlington, Taunton or wherever. Or rather to attempt to micro-manage. This may improve media coverage but it builds confusion and disheartenment throughout the NHS.

All the best-run large businesses know that those at the top should lead, not manage. The first level of management should be empowered to deal with the micro-stuff and thereafter the next level of management should deal with matters the lower level cannot sensibly address. Because the NHS is so very large, that lesson is the more important.

How can politicians be removed from NHS management? Simple. We have a relatively new, well experienced, NHS England Chief Executive. He seems excellent and a great improvement on his predecessor. NHS England and the other national NHSs should be converted into public corporations, like the BBC, i.e. a stand alone operations funded and responsible to government but managed, day to day, independently. Whether to close, say, a cottage hospital would be a matter for NHS England. Politicians will still, rightly, lobby but they should not be making the decision.

Our political leaders should lead, not second guess local NHS doctors and managers. In addition to setting the budget, politicians should agree the budget and the strategy, i.e. what, overall, we should expect for our money. Then they should get out of the operating theatre.

A neat solution to the vaccine problem

A bit of free riding is inevitable in a free society. But sometimes you get so much that it ruins things for everyone. To stop the spread of infectious diseases, you need a certain number of the 'herd' to be immune to protect unvaccinated people from the disease's spread. In some parts of the US, after years of (baseless) scaremongering about the MMR vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella, so many parents have now chosen not to vaccinate their children that this herd immunity no longer exists. Until recently they were able to free ride on vaccinated children and avoid the disease, but now measles is staging a comeback.

If it were only the children of these parents who were at risk, we might judge that risking their lives was a price worth paying for parental autonomy, depending on how lethal the disease was. But some children (and adults) cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons or because they are too young, so there is a clear external cost to others.

Because of that, depending on the lethalness of the disease, there is a case for government intervention, but it would still be nice to minimise coercion if possible. KCL academic Nick Cowen suggested one elegant way of doing that:

Modest proposal: pay parents of new borns about £2,000 ($3,000) on completion of all vaccines on a standard schedule, or on submission of a medical exemption certificate (just to be fair to children with genuine vulnerabilities to vaccines).

That should get everyone enrolled apart from the truly rich and stupid, and bring herd immunity (the public good we are looking for) up to scratch. If that doesn't do it, double it. It functions as a good excuse to channel more money to families with young children - think of it as an upfront capital grant. The distribution is so broad that it will have few dead weight losses.

I imagine this would probably work, and it avoids having to put anyone in jail or take anyone's children away from them.

If only the people who rule us actually knew anything

Hayek pointed out that it's impossible for the centre to have enough information to be able to plan the economy. In one sense therefore, to find that our rulers are ill informed is consoling: Hayek was in fact right. In another it's not so good, for they will insist on gabbling on about things they really don't understand. Today's example is Tim Yeo:

Yeo believes fossil fuel companies must prepare themselves for a different kind of low carbon world.

“There may well be national [carbon] performance standards. There may well be caps everywhere. We now have a nuclear non-proliferation treaty, we may have then a coa-fired power station non-proliferation treaty and you can monitor these things externally.

“Or we may have a carbon price at $50 and investors think ahead so they think the world will have to be a low carbon one in the 2030s and pension funds with 25 year time horizons must take this into account. So the oil companies and the gas companies have to recognise this.”

OK. And here is the head of Shell indicating that they know this.

There’s much to do if we are to build a lower-carbon, higher-energy future. For Shell’s part, we wholeheartedly support the World Bank’s recent call for a carbon price to be applied throughout the global economy. Carbon pricing is one vital step, but there’s a long road ahead. To build the energy future we need, government, business and civil society must work together. With the right approach, one characterized by pragmatism, it can be within our reach. And, as CEO, I am determined that through our production of natural gas and our efforts to advance CCS, for example, Shell will continue to play our part.

Further, Shell has made it very clear that they already apply a carbon price in their evaluations of future investments (the only place that it's of any importance, sa projects currently producing are of course sunk costs).

So that Yeo ill informed in the specifics. But he's also ill informed in theory as well. He's getting very het up about the idea of "stranded reserves". This is the idea that the reserves that the oil companies are thinking about pumping up in 30 years' time never will be pumped up because of those climate change worries. Therefore those oil companies must recognise that risk on their balance sheets today. Write down the future value of those reserves perhaps. Which is simply an idiot thing to say.

Because we've had that whole dang report from Lord Stern discussing exactly this point. In which he goes on for several chapters pointing out that we shouldn't use market interest rates to measure the costs of something far in the future. OK, so, great, we don't when we talk about the costs of climate change. For if we did then those future costs would be, in he money of today, so small that we'd never do anything about it all. OK, make up your own minds on what you want to think about that.

But look at what that means about the values of those future reserves. We are discounting them to their present value at market interest rates. Because, obviously, we're valuing Shell's shares not at the value of those reserves in 30 years time but at the net present value discounted by market interest rates. Thus the value of those future reserves as contained in today's Shell price is piffle. Near nothing, because as Stern pointed out, discounting at 30 years and more at market rates makes something worth near nothing.

Thank goodness we don't have a planned economy, eh, given then knowledge held by those who would be doing the planning.

Economic Nonsense: 8. The world is running out of scarce resources

Curiously, the opposite is true: so-called 'scarce' resources are actually becoming more plentiful. Our technical ability to extract resources, including things like copper, zinc, chromium and manganese, is increasing faster than the rate at which we are using up existing 'reserves.' We use the term 'reserves' to denote the supply which can be extracted economically with current technology. For most of these resources our reserves are increasing. We can measure the relative availability of these resources by looking at their price. For many of them it has been going down over several decades, indicating a relative excess of the supply of them over the demand for them. Julian Simon won a famous public wager with Paul Erlich, predicting lower prices for an agreed basket of resources, and Erlich duly paid up when he lost.

If any resource does become genuinely scarce, the price rises, and this signals to people that they should use less of it, turning to substitutes where they have become more economic to develop. It also tells people to produce more of the scarce resource, with the higher price making previously marginal sources now more economic to develop. The price mechanism thus acts to counter their scarcity by reducing demand and augmenting supply.

Oil and gas were long thought to be exceptions to this trend, but even here technology has given us access to new supplies. Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has made available sources of oil and gas from places less volatile politically than those we previously depended upon. Prices have tumbled, and cheap shale gas is enabling us to shut down coal-fired power stations and switch to much cleaner gas-powered ones. Some estimates put the supply of shale gas as sufficient to supply projected needs for the next 200 years. Long before then, however, photovoltaic technology will have allowed solar power to overtake gas in its cheapness. Contrary to what doomsayers claim, we are running out of neither resources nor energy.

Hard-headed misunderstandings

Today I was on BBC World talking about obesity. My opposite number Tam Fry pointed out that the obese cost the rest of us while they are alive through their use of the NHS and other state services. I pointed out that they don't totalled up over the lifetime because the obese die earlier and take much less out in pensions and end-of-life care.

In saying this I was trying to make the point that this doesn't mean we shouldn't care about obesity, or that it's (heaven forbid!) a good thing because they cost the rest of us less. Are people so obsessed with the government's balance sheet that pointing out the obese cost the government less by dying earlier seems equivalent to saying I want them to die earlier?

My point was that most of the costs of obesity are to the individual, not to society. There is no harm principle argument here that we should intervene into their lives because they are hurting others. The case for intervening into the lives of the obese would be to make them better off, because say, obesity shortens their lives, makes them more likely to get diabetes, or makes them less happy.

Now I don't think there's never a case for paternalistic intervention (we can all think of crazy thought experiments) but I do think we should be very careful before we decide we can run someone's life for them. That's because usually the government gets things wrong when it tries to plan on other people's behalves.

Most people would not like to live in a society where people are not at least in some cases free to take the steps that lead to obesity—even if overall they'd prefer there were fewer obese people. Most people would find it rather chilling to have a society where the diets and exercise regimes of the obese were centrally managed and rigidly enforced.

By contrast, the Mexican 'squats for bus tickets' scheme, though very likely to be ineffectual, is probably not such a bad idea.

Economic Nonsense: 7. New technology destroys jobs

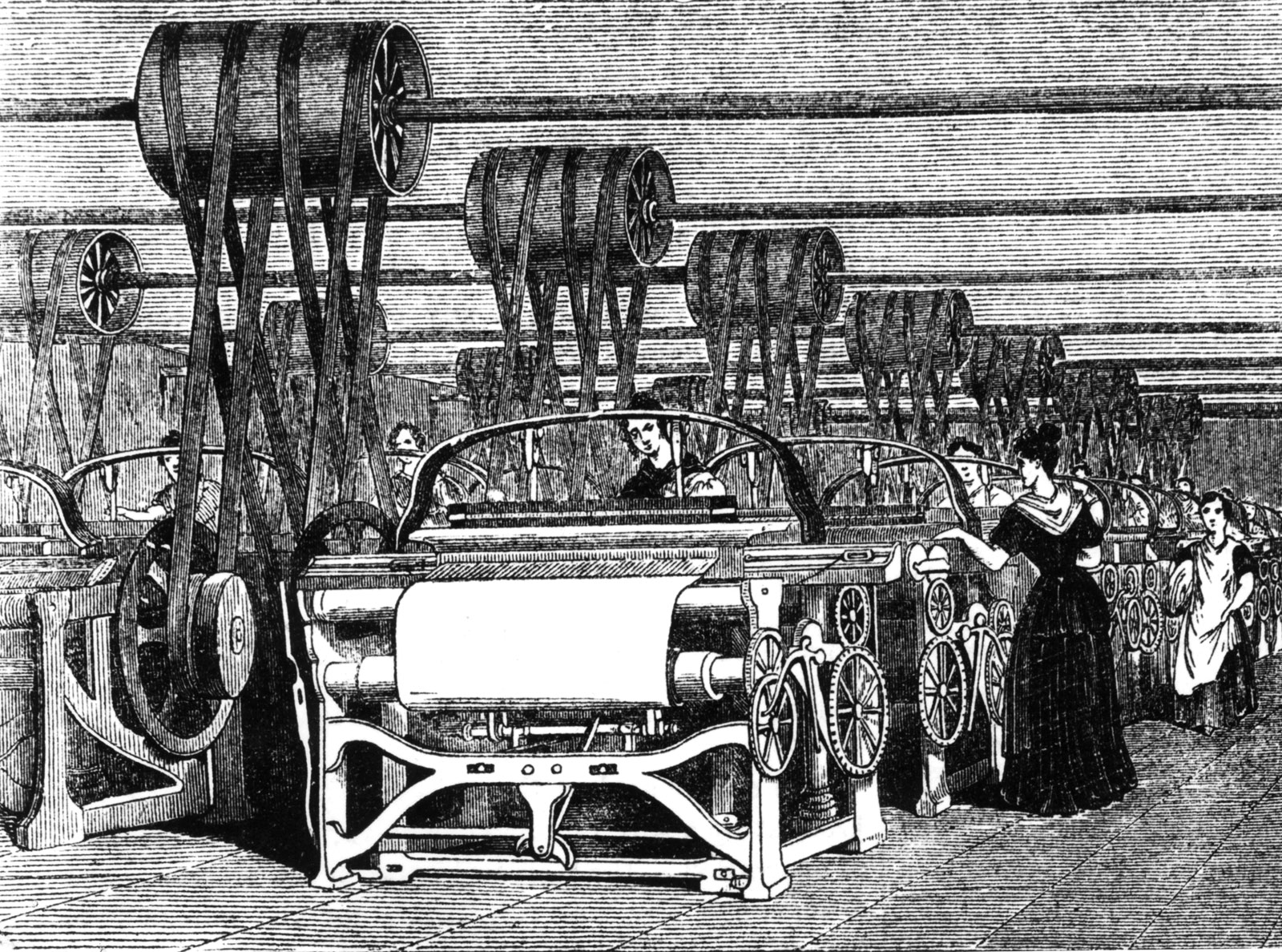

This is partly true, but in a misleading way. New technology has often displaced people from their traditional occupations, but in doing so it has created the wealth that has enabled vastly more jobs to be created than were lost. Agricultural technology meant far fewer jobs for farm workers, but it also meant cheaper, more abundant food that left people able to afford things sustained by newer jobs. A similar effect occurred with early textile technology. Spinners and weavers were displaced, but cheaper, mass-produced textiles enabled people to afford other things that led to other jobs. This is how economic progress is made. People develop new products and new processes that people prefer over what they were doing before. Jobs are lost and more are created as part of that churn.

Voices are often raised against the change, especially by those affected, with calls for restrictions to be imposed on new technology in the name of protecting jobs. Sometimes it has led to violence. The Luddites smashed machinery, while the Saboteurs were named from throwing their wooden shoes (sabots) into the machines to wreck them. This was done in a vain attempt to halt the march of progress.

New technology can bring hardship upon those affected by it, and some of those displaced can find it hard to secure alternative employment. Governments, rather than attempting to stop new technology, sometimes try to ameliorate some of its effects by funding schemes that help retrain and if necessary relocate those most affected by it.

Sometimes people will ask where the new jobs will come from if technology displaces traditional ones. The question cannot be answered because the future is inherently unpredictable. New technology makes things cheaper, and that leaves people richer, with more money to spend on other things. We don't know what those other things will be, but we do know that they will involve new types of jobs. New technology, in making manufactured good cheaper, has left people with more to spend on services industries, and there are more jobs in total than there were. This is how new technology works. It destroys some jobs and creates more.