The Living Wage is a false solution to our problems

I normally agree with the Centre for Policy Studies on economic issues, so I was surprised to see Adam Memon’s call for a mandatory ‘Living Wage’ last week. Philip Booth has already written a post criticising Memon’s original piece, but I’d like to add my perspective to Adam’s response to Philip, posted today. To be clear, Adam prefers “tax cuts, deregulation and other supply-side measures to boost productivity”. He and the CPS have long argued for tax cuts for the poor. This is admirable, and as Adam says it deserves to be acknowledged.

My main contention is that Adam is comparing apples with oranges by using the impact of historical increases in the National Minimum Wage (NMW) to justify a future rise to the NMW to Living Wage levels. There is a lot of evidence against his position that he ignores.

Adam says that “an objective reading of the studies of the impact of the National Minimum Wage can only lead to the conclusion that it has boosted the incomes of the low paid without particularly damaging employment”. Correct. There does not seem to be much, if any, good evidence that the NMW has increased unemployment in the UK.

But this doesn’t tell us that employment would not be higher without rises to the minimum wage. Simply looking at times when we have raised the NMW, and looking at whether unemployment has risen or not, as Adam does once, is extremely crude – there are of course many other factors going on, and without an analysis that attempts to control for those factors we have no idea what the counterfactual would be. But, yes, there have been more sophisticated studies in the UK that do suggest that the NMW has not harmed employment compared to there being no NMW.

Adam says that “This is quite a big deal because it does rather make the traditional argument that the minimum wage would destroy jobs somewhat out-of-date”. But, unless we think there is something particularly unique about the UK’s labour market, the UK is not the only place we have to look at.

Internationally, most of the evidence is that increases in the minimum wage do increase unemployment at the margin. I looked at some of this last year:

Neumark and Wascher's review of over one hundred studies found that two-thirds showed a relatively consistent indication that minimum wage increases cause increases in unemployment. Of the thirty-three strongest studies, 85 per cent showed unemployment effects. And “when researchers focus on the least-skilled groups most likely to be adversely affected by minimum wages, the evidence for disemployment effects seems especially strong”. There is evidence that suggests that minimum wages deter young workers from acquiring these skills that allow them to get better jobs in the long run.

Of course there are times when this does not happen, but most of the time it does. Most of this evidence is based on US data, and much of it compares employment rates in similar US states where one has had a minimum wage rise and the other has not.

Though UK evidence might be the most relevant evidence we have, we would need a very good reason to completely ignore the international evidence and suppose that the UK experience is all that we should look at.

I am certain that Adam agrees, because he has cited international evidence in discussions about the UK in the past. And rightly so.

Is the UK special? Maybe. But the Low Pay Commission seems to disagree, because its recommended increases have been very low compared to what Adam is proposing. Similarly, the Living Wage Foundation does not call for a mandatory Living Wage.

Distributionally, if some people are put out of work but others receive pay rises, this may well be a negative. Adam says that “There are of course some who lose out from the minimum wage but there are many more who benefit”, but concludes that “broadly speaking the minimum wage is a net positive.”

But taking all of one person’s earnings and distributing them among other people who are already in work is likely to be harmful overall, because of diminishing marginal utility. If there is an unemployment effect it may well be an upwards income redistribution from now-unemployed people to the people who hang on in their jobs.

I do think the Low Pay Commission has done a good job at keeping NMW increases quite restrained. That’s why I suspect they would balk at the idea of raising the NMW to the Living Wage level for the foreseeable future. It’s simply not convincing to compare previous rises that the Low Pay Commission has deemed safe with a future rise that it presumably deems unsafe.

Note that productivity has been very low recently, and the Low Pay Commission has barely raised the NMW as a result.

I find it extremely implausible when Adam defends his claim that the Living Wage might lead to extra productivity gains from workers. This concept is known as ‘efficiency wages’ – a well-paid worker is often a more profitable one.

But firms are profit-seeking, so wouldn’t they be doing this already? Adam addresses this by saying that “often some of these productivity gains through eg reduced absenteeism are unanticipated by firms because unsurprisingly, they don’t always have perfect information” – fine, but these firms will be the exception, not the rule. Yes, firms sometimes miss out on profit opportunities – this doesn’t mean that I or Adam or anybody else knows better.

I enjoyed Alex Tabarrok’s recent post on this, "The False Prophets of Efficiency Wages". He points out that ‘efficiency wages’ were actually studied by economists as a way of explaining unemployment:

In the original efficiency wage literature there is no wishful thinking–no idea that we can have more of everything that we want without tradeoffs. Instead of being desirable, the efficiency wage is a problem because lower wages would reduce unemployment and be better for the economy as a whole.…

Firms routinely track turnover and productivity and they are well aware that higher wages are a possible means to reduce turnover and increase productivity although, as it turns out, not necessarily the most effective means. Indeed, the whole field of workforce science deals with retention, turnover and job satisfaction and the relationship of these to productivity and it does so with more nuance than do most economists. Thus, it’s simply not plausible that large numbers of firms on the existing margin can increase wages, profits and productivity.

To be fair, Adam suggests that his Living Wage rise would be offset by cuts in taxes for business. If these were specifically cuts to the cost of hiring workers this may actually work: cutting employer NICs for NMW workers workers might offset the extra cost of paying the worker the Living Wage. But this would just be a roundabout way of cutting the income taxes or employee NICs of those workers. The Living Wage would be doing none of the heavy lifting, and would still exclude some workers from jobs.

Adam claims that tax credits and other in-work benefits subsidise employers by letting them pay their workers less. I’ve always found this a strange claim. Why would workers’ wage demands fall just because they’re getting top-up money from elsewhere? Do lottery winners ask for lower wages? In any case, he does not provide evidence of this. The consensus from the literature I have seen is that both payroll tax cuts and wage subsidies go to the workers, without driving down wages. So there is no subsidy effect.

In light of all this, my basic view is that raising the minimum wage always risks creating unemployment, and raising it as high as Adam wants would run a very large risk of creating unemployment. I believe that low pay will be the economic problem facing my generation, as unemployment was for my parents’ and grandparents’ generations. To address it, I prefer cash transfers like the Basic Income and anything that boosts innovation, so we can improve people’s productivity and the total stock of wealth.

At best the Living Wage will act as a roundabout way of cutting taxes on workers. At worst it will put many people out of work. I admire Adam’s willingness to challenge the orthodoxy on our side, but in this case I believe that the bulk of the evidence in favour of the free market orthodoxy. The Living Wage is a siren call – a seductive but false solution to the problem of low pay. We should reject it.

The case against caring about inequality at all

Readers of this blog will probably not need convincing that inequality is not something to worry about. We’re more interested in reducing absolute poverty. If you become £100 richer, and I become £50 richer, I say that’s a good thing. But because we’ve become less equal, someone who is concerned with inequality alone would not. But even given this, inequality might matter. Whether we think they should care about it or not, people do, and it makes no more sense to think of that as a ‘bad’ or unimportant desire than thinking a passion for expensive or high-tech watches is bad.

And because people care about it, they might act on it. If inequality makes a revolution or populist, anti-market governments more likely, as Noah Smith suggests it does, then it might reduce investment and growth as well.

Crucially, these harms from inequality come from people’s perceptions of inequality, not necessarily actual inequality. Which makes a new NBER working paper, “Misperceiving Inequality”, rather interesting (hat tip to Bryan Caplan, who quotes some of the key parts directly).

The paper shows that most people know very little about the extent and direction of income inequality in their societies, or where they fit in to the income distribution. This holds for wealth as well as income.

This isn’t a pedantic complaint about imprecision. One question asked people to choose which of five diagrams, above, best described where they live. Responses differed significantly between different countries (68% of Latvians chose Type A, 2% of Danes did), but in almost every country a majority got it wrong.

Globally, respondents were able to pick the “right” diagram only slightly better than randomly – 29% got it right, compared to a random baseline of 22.5%. Accuracy differed significantly between countries: 61% of Norwegians got it right, 40% of Britons did, 5% of Ukrainians did. In only five countries out of forty did more than half of respondents guess correctly. (All this uses post-tax-and-transfer data; people’s accuracy is much worse if you use pre-tax-and-transfer data.)

And respondents weren’t even close – looking at how many people were only one diagram off the right one, respondents only did one percentage point better than random (69% versus 68%). As the authors note, “with only five options to choose between, getting within one place of the correct option is not a very difficult task”.

The paper also shows that people are terrible at judging where they fall in the income distribution – 40% of British second-home owners said they were in the bottom half. 3% said they were in the top 10%.

Crucially, given worries about investment and political instability, “In countries where inequality was generally thought to be high, more people supported government redistribution. But demand for redistribution bore no relation to the actual level of inequality.”

There’s too much in the paper to cover in one blogpost, but the results are extremely clear: people’s perceptions of inequality are really, really inaccurate – that holds globally and in all but a handful of Scandinavian countries.

There are some good arguments in favour of reducing inequality based on how people perceive it – that it makes people unhappy, more left-wing, more prone to revolution, more hateful to the people around them.

But this paper shows that those perceptions are related to the realities of inequality only very slightly, if at all. Redistributive policies that reduce actual inequality are costly, and because actual inequality is barely related to perceptions of inequality they may do little to make the country more stable or market-friendly. If these are important problems, we can only solve them by making people feel less unequal – not by making them less unequal in fact. In short: even if people’s perceptions of inequality matter, the reality does not.

Why William Nordhaus was right and Nick Stern wrong

Given that coal fired power stations seem to be closing down left right and centre we might think this is a victory in the fight against climate change. Sadly though what we're actually seeing is the result of people following the advice of thwe wrong economist. It was William Nordhaus who was correct, Nick Stern who was wrong. Ambrose:

The British electricity group SSE (ex Scottish and Southern Energy) is already adapting to the new mood. It will close its Ferrybridge coal-powered plant next year, citing the emerging political consensus that coal "has a limited role in the future".

The IMF bases its analysis on the work Arthur Pigou, the early 20th Century economist who advocated taxes to stop investors keeping all the profit while dumping the costs on the rest of society.

So why has the power station closed early, citing soaring running costs, when coal prices are at an eight-year low and when it was modernised to stay open until 2023?

The Carbon Price Floor is arguably one of the most hidden and unknown but ultimately damaging pieces of modern industrial taxation. To use a shorter and more descriptive title, this carbon tax is slowly forcing the premature closure of the backbone of our electricity generating base.

As we regularly say around here, if there is an externality, one which cannot be dealt with by market or private means, then yes Pigou and his tax can be the right solution.

However, there's a difference possible in the way that it's applied. Roughly speaking the UK government has followed Stern's advice: here's the amount the tax should be, impose it now. Which is why these plants are closing at such great expense in stranded assets.

What should have been done is the Nordhaus approach. Sure, we need the tax but it would be better to work with the capital and technological cycle than against it. Thus, have a low tax now rising into the future. In this manner we'll still get the use of those capital assets that we've already built while also making sure that the next generation, to replace the current as they fall to bits, are non-emitting.

Don't forget, we're not imposing this tax to raise revenue: we're imposing the tax to reduce future emissions. And we obviously want to do this in the cheapest manner possible. Which is, as above, to use the current installed base until it falls apart and then rebuild it differently. Not, as the Stern prescription makes us do, close down perfectly good plant right now.

We should, obviously, be at least somewhat grateful that the government did listen to economists on this. It's just rather sad that they listened to the wrong one.

A blanket ban on psychoactive substances makes UK drugs policy even worse

It is a truth under-acknowledged that a drug user denied possession of their poison is in want of an alternative. The current 'explosion' in varied and easily-accessible 'legal highs' (also know as 'new psychoactive substances') are a clear example of this.

In June 2008 33 tonnes of sassafras oil - a key ingredient in the production of MDMA - were seized in Cambodia; enough to produce an estimated 245 million ecstasy tablets. The following year real ecstasy pills 'almost vanished' from Britain's clubs. At the same time the purity of street cocaine had also been steadily falling, from over 60% in 2002 to 22% in 2009.

Enter mephedrone: a legal high with similar effects to MDMA but readily available and for less than a quarter of the price. As the quality of ecstasy plummeted (as shown by the blue line on this graph) and substituted with things like piperazines, (the orange line) mephedrone usage soared (purple line). The 2010 (self-selecting, online) Global Drug Survey found that 51% of regular clubbers had used mephedrone that year, and official figures from the 2010/11 British Crime Survey estimate that around 4.4% 16 to 24 year olds had tried it in the past year.

Similarly, law changes and clampdowns in India resulted in a UK ketamine drought, leading to dabblers (both knowingly and unknowingly) taking things like (the once legal, now Class B) methoxetamine. And indeed, the majority of legal highs on offer are 'synthetic cannabinoids' which claim to mimic the effect of cannabis. In all, it's fairly safe to claim that were recreational drugs like ecstasy, cannabis and cocaine not so stringently prohibited, these 'legal highs' (about which we know very little) probably wouldn't be knocking about.

Still, governments tend to be of the view that any use of drugs is simply objectively bad, so the above is rather a moot point. But what anxious states can do, of course, is ban new legal highs as they crop up. However, even this apparently obvious solution has a few problems— the first being that there seems to be a near-limitless supply of cheap, experimental compounds to bring to market. When mephedrone was made a Class B controlled substance in 2010, alternative legal highs such NRG-1 and 'Benzo Fury' started to appear. In fact, over 550 NPS have been controlled since 2009. Generally less is known about each concoction than the last, presenting potentially far greater health risks to users.

At the same time, restricting a drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 requires evidence of the harm they cause (not that harm levels always bear much relation to a drug's legality), demanding actual research as opposed to sensationalist headlines. Even though temporary class drug orders were introduced in 2011 to speed up the process, a full-out ban still requires study, time and resources. Many have claimed the battle with the chemists in China is one lawmakers are unlikely to win.

And so with all of this in mind, the Queen's Speech on Wednesday confirmed that Conservatives will take the next rational step in drug enforcement, namely, to simply ban ALL OF THE THINGS.

In order to automatically outlaw anything which can make people's heads go a bit funny, their proposed blanket ban (modelled on a similar Irish policy) will prohibit the trade of 'any substance intended for human consumption that is capable of producing a psychoactive effect', and will carry up to a 7-year prison sentence.

Somewhat ironically for a party so concerned with preserving the UK's legal identity it wants to replace the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights, this represents a break from centuries of British common law, under which we are free to do something unless the law expressly forbids it. This law enshrines the opposite. In fact, so heavy-handed and far-reaching is the definition of what it is prohibited to supply that special exemptions have to be granted for those everyday psychoactive drugs like caffeine, alcohol and tobacco. Whilst on first glance the ban might sound like sensible-enough tinkering at the edges of our already nonsensical drug policy, it really is rather sinister, setting a worrying precedent for the state to bestow upon citizens permission to behave in certain ways.

This law will probably (at least initially) wipe out the high street 'head shops' which the Daily Mail and Centre for Social Justice are so concerned about. However, banning something has never yet simply made a drug disappear. An expert panel commissioned by the government to investigate legal highs acknowledged that a 50% increase in seizures of Class B drugs between 2011/12 and 2013/14 was driven by the continued sale of mephedrone and other once-legal highs like it. Usage has fallen from pre-ban levels, but so has its purity whilst the street price has doubled. Perhaps the most damning evidence, however, comes from the Home Office's own report into different national drug control strategies, which failed to find “any obvious relationship between the toughness of a country’s enforcement against drug possession, and levels of drug use in that country”.

The best that can be hoped for with this ridiculous plan is that with the banning of absolutely everything, dealers stick to pushing the tried and tested (and what seems to be safer) stuff. Sadly, this doesn't seem to be the case - mephedrone and and other legal and once-legal highs have been turning up in batches of drugs like MDMA and cocaine as adulterants, and even being passed off as the real things. Funnily enough, the best chance of new psychoactive substances disappearing from use comes from a resurgence of super-strong ecstasy, thanks to the discovery of a way to make MDMA using less heavily-controlled ingredients.

The ASI has pointed out so. many. times. that the best way to reduce the harms associated with drug use is to decriminalise, license and tax recreational drugs. Sadly, it doesn't look like the Conservatives will see sense in the course of this parliament. However, at least the mischievous can entertain themselves with the prospect that home-grown opiates could soon be on the horizon thanks to genetically modified wheat. And what a moral panic-cum-legislative nightmare that will be...

Another sign of the looming apocalypse

That Guardian opinion columns will have only a marginal relationship to economics, maths or even reality is well known. But it is possible to find signs of the looming apocalypse even there, knowing that point.

Are you paid what you are worth? What is the relationship between the actual work you do and the remuneration you receive?The revelation that London dog walkers are paid considerably higher (£32,356) than the national wage average (£22,044) tells us much about how employment functions today. Not only are dog walkers paid more, but they work only half the hours of the average employee.

It is clear that the relationship between jobs and pay is now governed by a new principle. The old days in which your pay was linked to the number of hours you clocked up, the skill required and the societal worth of the job are long over.

There's never been a time when pay was determined by societal worth. Cleaning toilets is highly valuable societally: as the absence of piles of bodies killed off by effluent carried diseases shows. It's also always been a badly paid job. Because wages are not and never have been determined by societal worth. Rather, by the number of people willing and able to do a job at what price versus the demand for people to do said job at that price. You know, this oddity we call a market.

That a Guardian opinion column might opine that jobs should pay their social worth is one thing, to claim that the world used to work that way is an error of a different and larger kind.

We are surrounded by examples of this increasing disparity between jobs and pay. For example, average wages in western countries have stagnated since the 1980s,

And there's the maths error. For that's not true either. Yes, as we know, wages have been falling in recent years but according to both Danny Blanchflower and the ONS real wages are still, after that fall, 30% or so higher than in the 80s (median wages). 30% over three decades isn't great but it's also not to be sniffed at: and it's also not stagnation.

But we expect such errors from the innumerates who fight for social justice or whatever they're calling it this week. At which point we come to the signs of the apocalypse:

Peter Fleming is Professor of Business and Society at City University, London.

Actually, he's in the Business School:

Peter Fleming Professor of Business and Society

That long march through the institutions has left us with professors at business schools believing, and presumably teaching, things that are simply manifestly untrue.

Woes, society to the dogs, apres moi la deluge etc.

It's not a happy thought that this sort of stuff is being taught these days, rather than just scribbled in The Guardian, is it?

Torts and tortes

It's pretty hard to lose weight. A lot of evidence suggests that waist circumference is heritable, with as much as half the differences between individuals down to genes. But this genetic explanation probably doesn't explain social trends towards obesity; surely there haven't been enough generations of heavier people having more kids than less heavy people (do they even have more kids?)

The issue gets weirder when we discover that animals living in human environments are also getting fatter, even lab rodents eating controlled diets!

Whatever the explanation for the macro issue, it's refreshing to note that on the micro level, people are still responding to incentives. After a big 2002 anti-McDonald's judgement 26 US states passed rules making it much harder to sue fast food companies for causing your weight gain. After this, people seemed to take more responsibility for their own weight and health.

This finding comes from a new paper, "Do 'Cheeseburger Bills' Work? Effects of Tort Reform for Fast Food" (latest gated, earlier pdf) by Christopher S. Carpenter, and D. Sebastian Tello-Trillo. Here is the abstract:

After highly publicized lawsuits against McDonald’s in 2002, 26 states adopted Commonsense Consumption Acts (CCAs) – aka ‘Cheeseburger Bills’ – that greatly limit fast food companies’ liability for weight-related harms.

We provide the first evidence of the effects of CCAs using plausibly exogenous variation in the timing of CCA adoption across states. In two-way fixed effects models, we find that CCAs significantly increased stated attempts to lose weight and consumption of fruits and vegetables among heavy individuals.

We also find that CCAs significantly increased employment in fast food. Finally, we find that CCAs significantly increased the number of company-owned McDonald’s restaurants and decreased the number of franchise-owned McDonald’s restaurants in a state.

Overall our results provide novel evidence supporting a key prediction of tort reform – that it should induce individuals to take more care – and show that industry-specific tort reforms can have meaningful effects on market outcomes.

I'm not saying individual responsibility always works but maybe some of the blame for obesity is down to individual choice.

Well, yes and no Professor Krugman, yes and no

The economics of this is of course correct For Paul Krugman is indeed an extremely fine economist:

We may live in a market sea, but most of us live on pretty big command-and-control islands, some of them very big indeed. Some of us may spend our workdays like yeoman farmers or self-employed artisans, but most of us are living in the world of Dilbert.

And there are reasons for this situation: in many areas bureaucracy works better than laissez-faire. That’s not a political judgment, it’s the implicit conclusion of the profit-maximizing private sector. And people who try to carry their Ayn Rand fantasies into the real world soon get a rude awakening.

The political implications of this are less so, given that Paul Krugman the columnist is somewhat partisan.

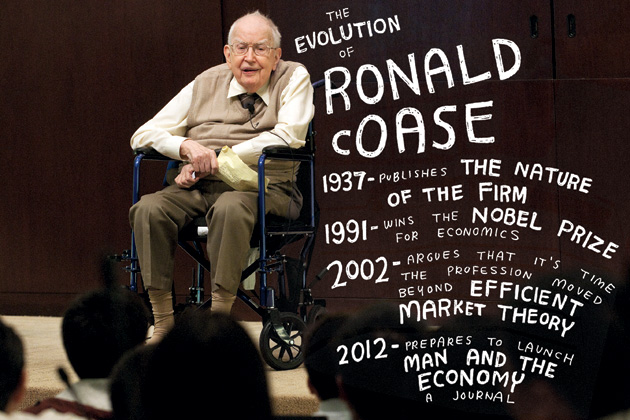

And of course that implication is that since that private sector (as Coase pointed out a long time ago) uses bureaucracy at times then we should all shut up and simply accept whatever it is that the government bureaucracy decides to shove our way.

Which is to slightly miss the point: yup there's command and control islands in that sea. Bit it's that sea that srots through those islands, sinking some and raising others up into mountains. Which is something that doesn't happen with the monopoly of government bureaucracy: they don't allow themselves to get wet in that salty ocean of competition.

That planning and bureaucracy can be the most efficient manner of doing something? Sure. That sometimes it's not? Sure, that's implicit, explicit even in the entire theory. How do we decide? Allow that competition. It's the monopoly of the government bureaucracy that's the problem, not that we somtimes require pencil pushers to push pencils.

RIP John Nash

In a Think Piece for the Adam Smith Institute, Vuk Vukovic pays tribute to the endlessly influential theorist John Nash:

It is with great sorrow we hear that one of the greatest minds in human history died this weekend in a car crash with his wife while they were returning home from an airport. John Forbes Nash Jr., was widely known as one of the founders of cooperative game theory whose life story was captured by the 2001 film "A Beautiful Mind", is truly one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. His contributions in the field of game theory revolutionized the way we think about economics today, in addition to a whole number of fields - from evolutionary biology to mathematics, computer science to political science.

You can read the whole piece here

In memoriam: John Nash

It is with great sorrow we hear that one of the greatest minds in human history died this weekend in a car crash with his wife while they were returning home from an airport. John Forbes Nash Jr., was widely known as one of the founders of cooperative game theory whose life story was captured by the 2001 film "A Beautiful Mind", is truly one of the greatest mathematicians of all time. His contributions in the field of game theory revolutionized the way we think about economics today, in addition to a whole number of fields - from evolutionary biology to mathematics, computer science to political science.

John Nash was born in 1928 in Bluefield, West Virgina. Even as a child he showed great potential and was taking advanced math courses in a local community college in his final year of high school. In 1945 he enrolled as an undergraduate mathematics major at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (today Carnegie Mellon). He graduated in 1948 obtaining both a B.S. and an M.S. in mathematics and continued onto a PhD at the Department of Mathematics at Princeton University. There's a famous anecdote from that time where his CIT professor Richard Duffin wrote him a letter of recommendation containing a single sentence: "This man is a genius". Even though he got accepted into Harvard as well, he got a full scholarship from Princeton which convinced him that Princeton valued him more.

While at Princeton, already on his first year (in 1949) he finished a paper called "Equilibrium Points in n-Person Games" (it's a single-page paper!) that got published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (in January 1950). The next year he completed his PhD thesis entitled "Non-Cooperative Games", 28 pages in length, where he introduced the equilibrium notion that we now know as the Nash equilibrium, and for which he will be awarded the Nobel Prize 34 years later. It took him only 18 months to get a PhD: he was 22 at the time.

While at Princeton he finished another seminal paper "The Bargaining Problem" (published in Econometrica in April 1950), the idea for which he got from an undergraduate elective course he took back at CIT. It was Oskar Morgenstern (the co-founder of game theory and the co-author of the von Neumann & Morgenstern (1944) Theory of Games and Economic Behavior) who convinced him to publish that bargaining paper. The finding from this paper will later be known as the Nash bargaining solution. At Princeton he sought out Albert Einstein to discuss physics with him (as physics was also one of his interests). Einstein reportedly told him that he should study physics after Nash presented his ideas on gravity, friction and radiation.

Illness and impact

After graduating he took an academic position at MIT, also in the Department of Mathematics, while simultaneously taking a consultant position at a cold war think tank, the RAND Corporation. He continued to publish remarkable papers (his PhD thesis in The Annals of Mathematics in 1951, another paper called "Two-Person Cooperative Games" in Econometrica in 1953, along with a few math papers). He was given a tenured position at MIT in 1958 (at the age of 30), where he met and later married his wife Alicia. However, things started to go wrong from that point on in his personal life and career. In 1959 he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, forcing him to resign from MIT. He spent the next decade in and out of mental hospitals. Even though he and his wife divorced in 1963, she took him in to live with her after his final hospital discharge in 1970.

Nash spent the next two decades in relative obscurity, but his work was becoming more and more prominent. Textbooks and journal articles using and applying the Nash equilibrium concept were flying out during that period, while most scholars that built upon his work thought he was dead. It was not only the field of economics - where the concepts of game theory were crucial in developing the theory of industrial organizations, the public choice school and the field of experimental economics (among many other applications) - it was a whole range of fields; biology, mathematics, political science, international relations, philosophy, sociology, computer science, etc. The applications went far beyond the academia; governments started auctioning public goods at the advice of game theorists, business schools used it to teach management strategies.

Arguably the most famous applications were to the cold war games of deterrence that explain to us why the US and Russia kept on building more and more weapons. The Nash equilibrium concept explains it very simply - it all comes down to a credible threat. If Russia attacks the US it must know that the US will retaliate. And if it does, it will most likely retaliate with the same fire-power Russia has. Which will lead to mutual destruction of both countries. In order to prevent a full-scale nuclear war (i.e. in order to prevent the other country from attacking), the optimal strategy for both countries is to build up as much nuclear weapons as they can to signal to the other player what they're capable of. This will prevent the other player from attacking. If they are both rational (i.e. if they want to avoid a nuclear war and total destruction) they will both play the same strategy and no one will attack. Paradoxically, peace was actually a Nash equilibrium of the arms race!

Long-overdue recognition

Little did Nash have from all this. He had no income, no University affiliation and hardly any recognition for his work. But this all changed in the 1990s when he was finally awarded an overdue Nobel Prize in Economics in 1994, with fellow game theorists John Harsanyi and Reinhard Selten "for their pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non-cooperative games".

His remarkable and actually very painful life story was perfectly depicted by his autobiographer and journalist Sylvia Nasar in her two books; "A Beautiful Mind" (on which the subsequent motion picture was based) and "The Essential John Nash", which she co-edited with Nash's friend from college Harold Kuhn (also a renowned mathematician). As Chris Giles from the FT said in his praise of the latter: "If you want to see a sugary Hollywood depiction of John Nash's life, go to the cinema. Afterwards, if you are curious about his insights, pick up a new book that explains his work and reprints his most famous papers. It is just as amazing as his personal story." The book contains a facsimile of his original PhD thesis, along with eight of his most important papers (from game theory and mathematics) reprinted.

After the Nobel Prize success things got better for Nash. By 1995 he recovered completely from his "dream-like delusional hypotheses", stating that he was "thinking rationally again in the style that is characteristic of scientists." Refusing medical treatment since his last hospital intake, he claimed to have beaten his delusions by gradually, intellectually rejecting their influence over him. He rejected the politically-oriented thinking as "a hopeless waste of intellectual effort". In 2001 he remarried his wife Alicia and started teaching again at Princeton, where he continued his work in advanced game theory and has moved to the fields of cosmology and gravitation.

The Phantom of Fine Hall, as they used to call him in Princeton due to his mystique and the fact that he used to leave obscure math equations on blackboards in the middle of the night, will never cease to raise interest, praise and awe. Nash was another perfect example of a thin line between a genius and a madman. Luckily, in the end, his genius prevailed.

So what is the Nash equilibrium?

The reason why this concept was so revolutionary was because it significantly widened the scope of game theory at the time. In the beginning, following the von Neuman and Morgenstern setting, game theory was focused mostly on competitive games (when the players' interests are strictly opposed one to another). These types of games were known as zero-sum games, limiting to a significant extent the scope of game theory. Nash changed that by introducing his solution concept so that any strategic interaction between two or more individuals can be modelled using game theory, where the most unique solution concept is the Nash equilibrium. Games are not zero-sum, they aren't pure cooperation nor pure competition. They are a mixture of both.

The idea of the Nash equilibrium resonates from the simple assumption of rationality in economics. The term rationality in economics is not the same as common sense rationality we all think about upon hearing this term. It refers to the idea that each individual will act to achieve his or her own objective (maximize their utility), with respect to the information the person has at his/her disposal. The concept of rationality in economics is therefore idiosyncratic - it depends on whatever a particular individual deems rational for themselves at a given point of time. It rests upon the idea that a person will never apply an action that hurts him/her in any way (lowers his/her utility).

The Nash equilibrium is the most general application of this idea. A non-cooperative game, according to Nash, is "a configuration of strategies, such that no player acting on his own can change his strategy to achieve a better outcome for himself". In other words, if there exists another strategy that can make an at least one individual better off, then the outcome does not satisfy the condition for a Nash equilibrium.

Let's look at an example. The most simplified example of how a Nash equilibrium solution concept works is the Prisoner's Dilemma game. Consider two robbers arrested for a crime. They are both being interrogated by the police in separate rooms. They are presented with two options (strategies): keep quiet (silent) or betray the other guy (betray). If they both remain silent, they both only get a light sentence of a year in prison for obstructing justice. If one betrays the other and the other guy keeps silent, the betrayer is released with zero imprisonment, and the other guy gets pinned for the whole crime and gets nine years in prison. If they both betray each other, they both get six years in prison. What's the optimal thing to do?

Applying the Nash equilibrium concept we need to find a strategy that is the best response of one player to whatever the other player may decide. When no players have any incentive to deviate from a set of strategies (strategies are always a pair in two-person games) we can say that this set of strategies is a Nash equilibrium.

Consider the game depicted in the table below:

It would seem that the best strategy they can apply is for both to keep silent. If they do, they both get only a light sentence. However this strategy set (-1,-1) is not a Nash equilibrium since at least one person has an incentive to deviate. In fact, they both do. If Prisoner 1 decides to defect and betray Prisoner 2, he gets 0 years in prison, while Prisoner 2 gets 9 years (third cell, with payoffs 0,-9). Prisoner 2 applies the exact same reasoning (second cell with payoffs -9,0). In the end since the better strategy is always to betray, they both play the same strategy (betray, betray) and end up with payoffs (-6,-6) which is the Nash equilibrium of this game. From this point no player can deviate and make himself better off. If Prisoner 1 decides to go for silent he risks getting 9 years in prison instead of 6. There is no way for them to reach a cooperative equilibrium in this simplified scenario.

Naturally, cooperative games do exist and they help us understand how game theory solves for example the free rider and the collective action problem. It was Elinor Ostrom (1990) who applied these concepts to reach her optimal solutions in solving the common pool resource problem in small groups with persistent interactions. Robert Axelrod (1984) is another, finding that even though the defection strategy is more rational, sometimes various other factors will result in a cooperative outcome between the players. The Nash equilibrium helped initiate a huge amount of research on these and many other problems within and outside the academia. The reason game theory is usually considered as the most applicable economic theory - in that it can be used to solve real-life problems - is purely thanks to John Nash.

Rest in peace.

Most notable papers:

"Equilibrium Points in N-person Games". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 36 (36): 48–9. (1950)

"The Bargaining Problem". Econometrica (18): 155–62. (1950)

"Non-Cooperative Games". Annals of Mathematics 54 (54): 286–95. (1951)

"Real Algebraic Manifolds". Annals of Mathematics (56): 405–21. (1952)

"Two-Person Cooperative Games". Econometrica (21): 128–40. (1953)

"The Imbedding Problem for Riemannian Manifolds". Annals of Mathematics (63): (1956).

"Continuity of Solutions of Parabolic and Elliptic Equations". American Journal of Mathematics 80 (4): 931-954. (1958)

Do we need the FCA?

Students of the Financial Conduct Authority will appreciate the FCA’s Business Plan 2015/16 which mostly sets out what it does, but also touches on what it achieves and its value for UK citizens. It is as close to accountability as the FCA gets.

What does the FCA do?

The core business is the supervision “of about 73,000 financial services firms operating in the UK, and we prudentially supervise those that are not covered by the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA). We look closely at firms’ business models and culture and use our judgement to assess whether they are sound and robust.” (p.63) Understanding each of 73,000 firms better than the manager of that firm is a Herculean task even with 3,060 staff and a budget of £460M. But that is only part of the FCA’s business.

Annex 2 lists 106 new EU regulatory initiatives in which the FCA is involving itself. It would be good to believe they were seeking to reduce the number, and simplify and reduce the burden, of the on the British financial sector and its consumers. There is no hint that such is the case. The FCA seeks “active engagement” which can be translated as assisting more rather than less.

In addition, the FCA has a programme of domestic regulation. Yet the FCA should not now be creating new financial regulations at all. Under the Brown administration’s agreement with the EU, Brussels is responsible for all new financial regulation leaving the UK solely with supervision. For the FCA to add new rules is not merely piling Pelion upon Ossa, it is undermining the City’s competitiveness and unnecessary. In a single market, a regulation is either needed everywhere or nowhere.

In June 2014, the Chancellor created a Fair and Effective Markets Review (FEMR) of financial services, co-chaired by the Bank of England, FCA and HM Treasury. The report is due next month but has been widely trailed. Before we see that review (due July), and in an effort to keep itself busy, the FCA has announced a further review (due spring 2016) covering some of the same ground, the Investment and Corporate Banking Market Study (ICBMS): “We are examining issues around choice of banks and advisers for clients, transparency of the services provided by banks, and bundling and cross-subsidisation of services.”

In addition Annex 1 lists 30 “current and planned market studies and thematic work” not all of which will lead to new regulation. Perhaps the most significant is the “Culture review”. There is no mention of whose culture, nor how and why it should be reviewed. Reassuringly the start and finish dates have yet to be decided.

So far as one can see from the business plan, the FCA has no central guiding principle to determine what it should do. The Financial Ombudsman Service deals with consumer complaints and the Competition and Markets Authority deals with policing fair markets and competition. By contrast, the FCA seems to involve itself without restraint in anything it feels like doing. It is no surprise that its costs are growing at 6% p.a.

Measuring performance against the statutory objectives

The Chairman, in his foreword to the plan, highlights the FCA’s “principal tool [for measuring success], our outcomes-based performance framework” (p.7). As searching that description did not reveal such a framework, he presumably is referring to the table below.

It is unusual, to say the least, to have a set of performance measures without a single number. And there is no discussion about whether these objectives, for that is all they are, can be attributed to the FCA or not. Most of them are what the firms do but it is impossible to know whether the firms’ performance improved, or quite possibly deteriorated, as a result of the FCA intervention. It may be hard for the firm to keep the consumer at the centre of its attention if the FCA is knocking on the door.

The paperwork I now have to complete for my stockbroker has multiplied two or three times as a result of “compliance” which I also have to spend £20 a time for. In all other respects, the service is exemplary, but this has tipped my stockbroker experience from satisfaction to complaint.

The “respected regulatory system” will let only the good firms know where they stand, leaving the miscreants, presumably, in the dark. Is low financial crime an indication of the FCA doing well or failing to detect crimes or, just possibly, the police deterring crime and catching criminals?

The Business Plan refers the reader to their quarterly data bulletin for the actual figures but, guess what?, these have little to do with the table above. They are:

-

Monthly number of people contacting FCA about consumer credit.

-

Outcomes of upheld complaints.

-

Annual volume of “approved persons”. There are about 20,000 p.a. and, in the last two years, not a single application has been rejected.

-

Attestations “are a supervisory tool used to ensure clear accountability and a focus from senior management on putting things right in regulated firms.” Basically they are individual senior executives promising to put things right. There were 74 of those in the year to March 2015.

-

Skilled person reports. There are 50-60 cases a year of consultants being called in to investigate matters more closely. The great majority are conducted by accounting firms at a cost of over £150M p.a. The quarterly data simply give the number, not the cost nor whether they are value for money, still less whether the FCA adds any value.

-

The number of financial promotions. The relevance of this item to FCA performance measurement is opaque.

The simple bottom line of this section is that there is no performance measurement of the FCA. It is an elaborate charade.

Value for Money?

In his Foreword, the Chairman also stated “We are also committed to working as efficiently as possible with firms to deliver value for money, as well as the right outcomes for consumers and the financial markets.” (p.7). This topic next arises, in any substantive way, on p.37: “We remain focused on the principles of good regulation and advancing our objectives in the most efficient and effective way. We will continue to measure and evaluate our impact and report publically [sic] on this. Our aim will be to be as effective as possible and focus our resources on the front line of regulation. In 2015 we will launch an Efficiency and Effectiveness Review, which will look at the value for money of areas of higher expenditure. As part of this we will review our governance and decision-making processes. To embed this we will have a new structure,”

This good intention is repeated a number of time in the pages following, e.g. “We will achieve this by delivering year-on-year improvements in effectiveness, efficiency and economy. One of the key drivers of our strategy is to increase our efficiency and effectiveness.” (p.72).

Nowhere does the plan indicate how the FCA’s effectiveness, efficiency and value for money should be measured, still less what the numbers are or should be. The nearest we get is the p.37 quote above. As some army wag wrote on a Berlin wall in the 1940s: “we tend to meet any new situation by reorganising; and a wonderful method it can be for creating the illusion of progress while producing confusion, inefficiency and demoralisation.”

There is no evidence of the FCA providing value for money or even understanding how that might be measured.

Conclusion

All the things the FCA does could be done as well, if not better, by other agencies:

-

Consumer complaints have vastly increased since the FCA and Ombudsman services were created. In the year to Match 2015 the FCA had 150,000 consumer contacts (almost all complaints) and the Ombudsman contacts have risen from 62,170 in 2003 to 512,167 in 2014. One has to wonder about cause and effect. There are undoubtedly too many cases coming to the FCA and Ombudsman Service but the answer to that is not to increase these quangos, and allow malpractice to grow, but to take systemic action to minimise malpractice and when it does not arise, pressure the firms to deal with the complaints themselves, e.g. by massively increasing the penalties on complaints upheld by these two quangos, including gaol sentences.

-

Consumer complaints do, and should, go to the Financial Ombudsman Service which has 2,400 staff of its own. The FCA deals with only about 25% and is not now needed.

-

As noted above, the FCA should not now be creating new financial regulations at all. It should be helping the EU deregulate, simplify and reduce the burden of financial regulation, not assisting the EU in undermining the City’s competitiveness. In a single market, a regulation is either needed everywhere or nowhere.

-

Much of the wholesale side of the FCA’s supervision is purely “prudential” because it overlaps with supervision by the Bank of England through the Prudential Regulatory Authority. The BoE should be left to get on with it.

-

About one third of the cost of the FCA relates to the investigatory work contracted out to professionals, largely accounting firms. It should not take more than a couple of people to choose the firms, the terms of reference and make out the cheques. This, and all remaining FCA functions, could be handled by the Competition and Markets Authority. Indeed that would be a better solution anyway to bring consistency to markets and competition policy.

It is hard to resist the conclusion that the FCA is not simply redundant but a drain on the effectiveness, resources and efficiency of the vital financial services sector. It should be abolished.