What glory that China is to eat less meat in future

There is a dancin' an' a singin' as China announces that the country will eat less meat in the future. At least that's what we would think is happening from the reports of this matter this morning.

The Chinese government has outlined a plan to reduce its citizens’ meat consumption by 50%, in a move that climate campaigners hope will provide major heft in the effort to avoid runaway global warming.

New dietary guidelines drawn up by China’s health ministry recommend that the nation’s 1.3 billion population should consume between 40g to 75g of meat per person each day. The measures, released once every 10 years, are designed to improve public health but could also provide a significant cut to greenhouse gas emissions.

About which we might say two things. The first being that the Chinese government has not laid out any such plans. What has happened is that the usual health wowsers have released a report saying that they think it might be a good idea if China's meat eaters didn't eat quite so much as they are projected to.

This is not so much a plan as a pious exhortation, akin to our own wowsers telling us that we should drink less or consume less salt. Something which we all take with a pinch of that latter as we all continue on with our lives as we wish.

The second is that of course this is not how to deal with climate change, attempting to monitor the rice bowls of 1.3 billion people. Yes, we know, we get endless stick for our insistence that assuming that there is a problem here then the solution is a carbon tax. But this is a good example of why it is the solution to that problem if the problem does indeed exist.

We want to have just the one intervention, just the one lever jammed into the sprogs of the economy. Not some myriad of plans and hopes and interventions few of which will work anyway. Change the price of emissions and we change the price of everything produced by making emissions. And thus the price of pork, or beef, in China becomes the correct price to optimise human utility in the face of climate change. As does, from that same one and single intervention, the price of using coal or solar for electricity production, the transport of green beans from Kenya or not, the use of a car or a bicycle to get to the pub and absolutely every other possible or potential intervention that anyone might want to make into the economy.

We are, normally, most hesitant to talk about interventions into those markets - externalities, whether positive or negative are one of the known exceptions to the general rule of leave well alone. Copyrights and patents are a useful intervention to solve the externality of the public goods nature of invention and innovation. A carbon tax is the best intervention to deal with the negative externality of emissions, assuming that such are indeed such.

On the very reasonable indeed grounds that the Chinese government releasing dietary guidelines about meat consumption isn't going to have much effect in a country rising up out of peasant destitution for the first time in human history. While changing the price will.

If anything needs to be done about climate change it is a carbon tax. Whether is a different question but those who insist that something must be but who do not insist upon the only efficient or sensible method of doing it are just not being serious.

The monetary policy origins of the Eurozone crisis

The typical view blames the Eurozone crisis on excessive debt, worsened by austerity. Some members like Greece built up far too much private and public debt before the crisis, the narrative runs, and they were unable to cushion its blow on the macroeconomy, since without control of their own currency, fiscal easing would make the debt problem worse in the short run.

I think the typical view is wrong. I think that certain Eurozone countries (again, Greece stands out) did have terrible economic policy regimes running up to the crisis, but that these were only tenuously linked to mass unemployment, repeated solvency crises, huge bailouts and years upon years of misery. I think that most of the debt crisis was driven by poor macroeconomic management by the European Central Bank, which held policy excessively tight.

There are casual ways of showing this. Consider, for example, how the ECB took far longer than the Bank of England and the Federal Reserve to buy assets and thus expand the money supply through Quantitative Easing.

In a free market, economic shocks lead to a higher demand to hold safe assets like currency, and free banks accommodate this by printing. Neither the BoE nor the Fed did enough to accommodate this market thirst, but they did print a lot of money, and ameliorate the problem somewhat. It took the ECB years to follow suit.

A new Mercatus paper by David Beckworth (pdf), one of my favourite economists, backs this simple analysis up with a more rigorous narrative analysis.

Although evidence exists of a relationship between (a) the debt buildup and austerity measures and (b) economic growth during the crisis, that same evidence, on closer examination, points to Eurozone countries’ common monetary policy as the real culprit behind the area’s sharp decline in economic activity. In particular, it seems that the European Central Bank’s tightening of monetary policy in 2008 and again in 2010–2011 not only caused two recessions but also sparked the sovereign debt crisis—and gave teeth to the austerity programs.

Beckworth goes on to propose a new rules-based monetary regime centred around a stable nominal GDP growth path. Not coincidentally, we here at the ASI favour such a scheme as the closest approximation of what would go on if we had a purely free market, and indeed a step in that direction.

The strangest complaint we've seen this week

That the economics of the music business have changed in recent years is something that we all know and is also obvious. That it is generally the live show which feeds musicians these days rather than sales of recorded stuff has become the stuff of cliche. Yet we do think it odd, strange even, that this should become a matter for complaint.

As things stand, could people at least stop pretending that it’s tickety-boo that artists have been forced on to a gigging treadmill just to make money? Part of me wonders whether this Marie Antoinette-ish “they can make money playing live” public insouciance is because people don’t want to deal with the fact that they’ve colluded in this disaster, by either not paying for their music, or paying peanuts. These people need to realise that, for myriad reasons, musicians scrabbling together a living mainly from constant gigging can’t remain a viable long-term option. Also that if they’re not careful, before too long, they’re going to end up with the music scene they deserve.

That the country is absolutely jam packed with people who will turn up for free and play to an audience of the proverbial two men and a dog is one reason why music doesn't pay all that well - in that sense it's rather like other forms of showing off like acting. Or even writing journalism. But leave that aside.

The underlying claim here is that musicians should be able to make a living by not playing music. Which strikes us as a most odd contention. Ditch diggers make their living by digging ditches. Journalists by putting words in order, think tankers by thinking. None of us or you expect to be paid for not doing our jobs, the ones we freely elected to do.

Quite why musicians should earn for not musicing is one of those mysteries. Should dancers be paid for not dancing? Pilots for not piloting?

Questions in The Observer we can answer

This might be from a letter to The Observer but still, it's one of those rhetorical questions that deserve an answer. That answer being that there is no "we" which directs what all in the society may do. This is a rather more important point that simply the usual rejection of what these particular fools state - it is a very much more general description of what makes the bedrock of a free society:

GM crops yield no benefits

The central pillars of your editorial on genetically modified crops – that there is consensus over the safety of GM and that such a consensus would mean the arguments were over – are flawed. (“Europe can no longer turn its back on the benefits of genetically modified crops”).

There is nothing like the level of scientific consensus over genetically modified organisms as there is on climate change. Rather than giving GMOs a clean bill of health, the US National Academy of Sciences reveals that there is still a lot that we don’t know. And hundreds of scientists worldwide have signed a document refuting this “consensus”. Commercial GM farming has caused what the report identified as “major agricultural problems”.

GM crops have failed to provide any obvious benefits for the environment or the millions of small farmers who produce the majority of the world’s food. As the NAS report confirms, they don’t increase crop yields. So the real question is: why do we continue to pursue this now outdated technology, when there are more innovative, fairer and greener ways of producing our food?

Clare Oxborrow Friends of the Earth

Vicki Hird War on Want

Liz O’Neill GM Freeze

Peter Melchett Soil Association

The Soil Association is, as we all know, the trade union for organic farmers, so to see them opposing GM is not a surprise. The others are a little more mystifying in their distaste.

But let us, just for the sake of argument here, accept their factual points being made, that GM doesn't benefit anyone very much (although we cannot resist pointing out that the reason they don't benefit small farmers is because they don't use them). That's not actually the point at all.

Rather, we have absolutely no evidence whatsoever that the use of GM is harmful to anyone, more importantly we have precisely zero evidence that such is harmful to anyone not making the decision to plant or grow GM. At which point the argument about whether to allow or not allow the use of GM is over.

For in a free society the only possible justification for the banning of something, the prevention of something, is that the use or doing of it causes harm to someone not actually doing the using or the doing. Sure, smoking, drug use, they can and do harm users. But as they only harm users there is no argument to ban them.

Perhaps, as asserted, there's no very great use to GM crops (we disagree, but see above the just for the sake of argument) but that they cause no harm means they must be permitted.

For there is no "we" planning society and what all of us 7 billion must do. There's just us 7 billion trying to rub along together and that's best done by all of us doing as we wish, the only things we ban being those which prevent others from doing so, as they wish.

Something that causes no harm is to be allowed, by definition. Just as Lord Melchett is free to grow the fodder for his organic beef herd as he wishes so is everyone else to be accorded the same freedom. Even if M'Lord Melchett disagrees.

An interesting proof of the efficient markets hypothesis

A proof as in to test rather than a proof as in, my word this is absolutely and everywhere correct, of the efficient markets hypothesis that is. And the EMH, just for those who don't know, does not say that markets are always and everywhere the efficient way of doing things. We ourselves are quite keen that we don't have a free market in private armies. The history books are quite plain that the Wars of the Roses weren't a fun time for us run of the mill people even if the people wielding the broadswords enjoyed themselves immensely.

All the EMH does state is that markets are efficient at processing the information about what prices should be in a market. Just about all economists sign on to this idea at some level - it's how strong the effect is which is muttered about. And a useful proof, in that sense of test, is to go and look at minor, very minor perhaps, issues which should affect prices and then see, well, have they affected prices?

Which brings us to this paper here:

As of this writing in June 2016, the markets are predicting Venezuela to be on the brink of default. On June 1, 2015, the 6 month CDS contract traded at about 7000bps which translates into a likelihood of default of over 90%. Our interest in the Venezuelan crisis is that its outstanding sovereign bonds have a unique set of contractual features that, in combination with its near-default status, have created a natural experiment. This experiment has the potential to shed light on one of the long standing questions that sits at the intersection of the fields of law and finance, the question of the degree to which financial markets price contract terms. We find evidence to suggest that at least within the confines of a near-default scenario, the markets are highly sensitive to even small differences in contract language.

This is all about those collective action clauses. Argentine debt did not contain any and thus those holdouts, after default, were able to campaign and sue and then get paid fully. A CAC being a clause which states that if 75%, or 85% or whatever %, of all bond holders agree to change the terms of the bond, accept a haircut, then the others, those potential holdouts, can be forced to accept. This sort of thing is entirely normal in takeover law for example, if 90% of shareholders agree to accept an offer then the other 10% can be forced to sell at that offer price.

Argentina had no CAC clause. Thus the holdouts won. In Greece, Greek law bonds were changed by the Greek Parliament to have a CAC. Greek English law bonds were not - thus the differential payouts to the two classes of Greek bonds. Here, the point is that Venezuela has a series of bonds outstanding, some with no CAC, some with one of 85%, others with ones of 75%.

So, if there's truth to the EMH then even these minor changes in contractual language should lead to differences in current prices. For the lower the percentage in a CAC the more likely it is that a bondholder will be forced into a cramdown in the event of a default. And the finding is that yes, the bonds are trading at different prices. Same maturities (as far as is possible to measure of course), same coupon, different CACs and different prices.

We have not here proved that the EMH is correct - that's not the way this sciencey stuff works. Rather, science works by having a hypothesis, testing that against reality, and as long as the evidence doesn't disprove the idea we can proceed with it as a working description of the universe until some aspect of that reality does disprove it. Scientific theories are thus true only in the sense that no one or no thing has yet disproved them.

So it is with our efficient markets hypothesis. We know of times when it is not true or at least less than wholly so, like when markets are not complete (Shiller's part of the Nobel is largely for this). But in complete markets like sovereign bond ones we at least haven't any evidence against the idea that the EMH is true. And thus our working assumption has to be that the EMH is true in such complete markets.

Let's be mature about pensions

Many years ago I promised myself I would jump off a bridge if I ever got interested in pensions. Then I did briefly get interested in them. This was during the 1980s where Britain’s company pension funds were larger than the rest of Europe’s put together. It seemed like an amazing, far-sighted arrangement. But to save myself from jumping, I quickly lost interest in pensions again – partly due to Nigel Lawson’s tax raid on their surpluses (which should have been left to grow in order to pay the pensions of future retirees) and Gordon Brown’s 1997 stealth-tax raid (which has since taken about £120 bn out of people’s pension funds. Those raids, I figured, were the death knell.

Which they were. Of Britain’s 6,000 company pension schemes, which promise final-salary-linked pensions to 11 million people, around 5,000 are in deficit.

And it’s not just unscrupulous asset strippers milking companies and leaving pensioners’ retirements underfunded. That, mercifully, is the tiny minority. As well as the tax raids (which continue, with another one from George Osborne just this year), and the onerous and expensive governance rules that Gordon Brown also imposed, but the impossibility of predicting things thirty or forty years into the future.

When these funds made their extravagant promises, which induced people to invest up to 20% of their wages in them, times were great. But then we had (Gordon Brown again) a massive fake boom followed by the inevitable massive real bust, with investment rates forced down to near zero. Meanwhile, Quantitative Easing has seen the Bank of England buying government bonds and keeping their prices high, which means their returns are low too. And pension funds have a lot invested in government bonds, because they are relatively safe. Add to that greater longevity (with life expectancy now ten years longer than when some of these pension schemes began), people expecting to retire earlier, more people moving jobs (which raises administrative costs) and the regulatory fees, and defined-benefit pension funds have had it.

What is the answer? In most cases, the funds were quite properly managed, with good investment and actuarial advice. But the world changed in major ways, and their promises became undeliverable. You could ask companies to make up the shortfall, but money doesn’t grow on trees, and that means lower wages and pensions for current employees, higher prices for customers, or lower dividends for shareholders (who are - you guessed it - often pension funds).

No, I think we have to have a serious conversation with pension scheme members. The promises were over-optimistic, sunk by a large measure of government greed and ineptitude, but even more by changes in lifestyle, healthcare, and investment returns. Will our politicians initiate such a conversation? Unlikely: they dread doing anything that will annoy pensioners, who are more likely to vote than any other group, and who jealously guard their entitlements.

But actually, the political turmoil we have seen in the UK, the EU and the US tell me that in fact, people no longer want politicians telling them that the world is rosy. They would much rather see politicians telling them the truth. In company pensions, bygones are bygones, the damage has been done, and we need to grit our teeth and work out what future benefits can be afforded. Not a pleasant conversation, but I think we are grown up enough to have it.

Proof perfect that supermarket food waste is not a problem

One of the more difficult things, as Douglas Adams pointed out, is to keep a sense of proportion about the world. It is easy, of course it is, to point to something or other and shout "That's a massive problem!" It's rather more difficult to look at something and ponder on whether it's actually an important problem. It is once we do the latter that we can actually work out whether this is something that we should devote efforts to sorting out or not.

And so it is with food waste from supermarkets. We're told that this is one of those massive problems. There are even those who insist that supermarkets themselves are the problem as a result of this waste. Consideration is necessary here:

Tesco has revealed that the amount of food waste generated by the supermarket giant increased to 59,400 tonnes last year – the equivalent of nearly 119 million meals.

119 million meals! That's a massive problem!

Well, no, not really. It's two meals a year, a little under that in fact, for each inhabitant of these isles. Interesting, certainly, but not exactly massive. And then there's this:

The amount wasted was the equivalent of one in every 100 food products sold by Tesco during the last financial year.

Or as we might put it, 1% of throughput. At which point it's worth going and looking at parts of the world that do not have the supermarket logistics chain. And that is the correct way to think of supermarkets. Not as simply shops that we go to, they're just the retail outlets of the logistics and production chain that stretches right back to the planting of the fields.

The FAO and others have pointed out that in countries reliant upon more traditional practices some 50% of food gets wasted between farm and fork. It is this which explains the reason why the world grows enough calories for all yet not all can eat enough calories. The supermarkets reduce that waste considerably at that cost of the trivial losses at the supermarkets themselves. No, it's not quite true that the net gain from having supermarkets is 49% of the harvested crop but it's getting on for that number.

Sure, distributing that 1% to the needy is a worthwhile thing to do, why not? But we do need to understand that it's not an important point. What is important is bringing that industrial logistics chain to those places which do not have it in order to save that 50% of the harvest.

Supermarkets, properly considered, are the cure for food shortages and waste, not the cause of them.

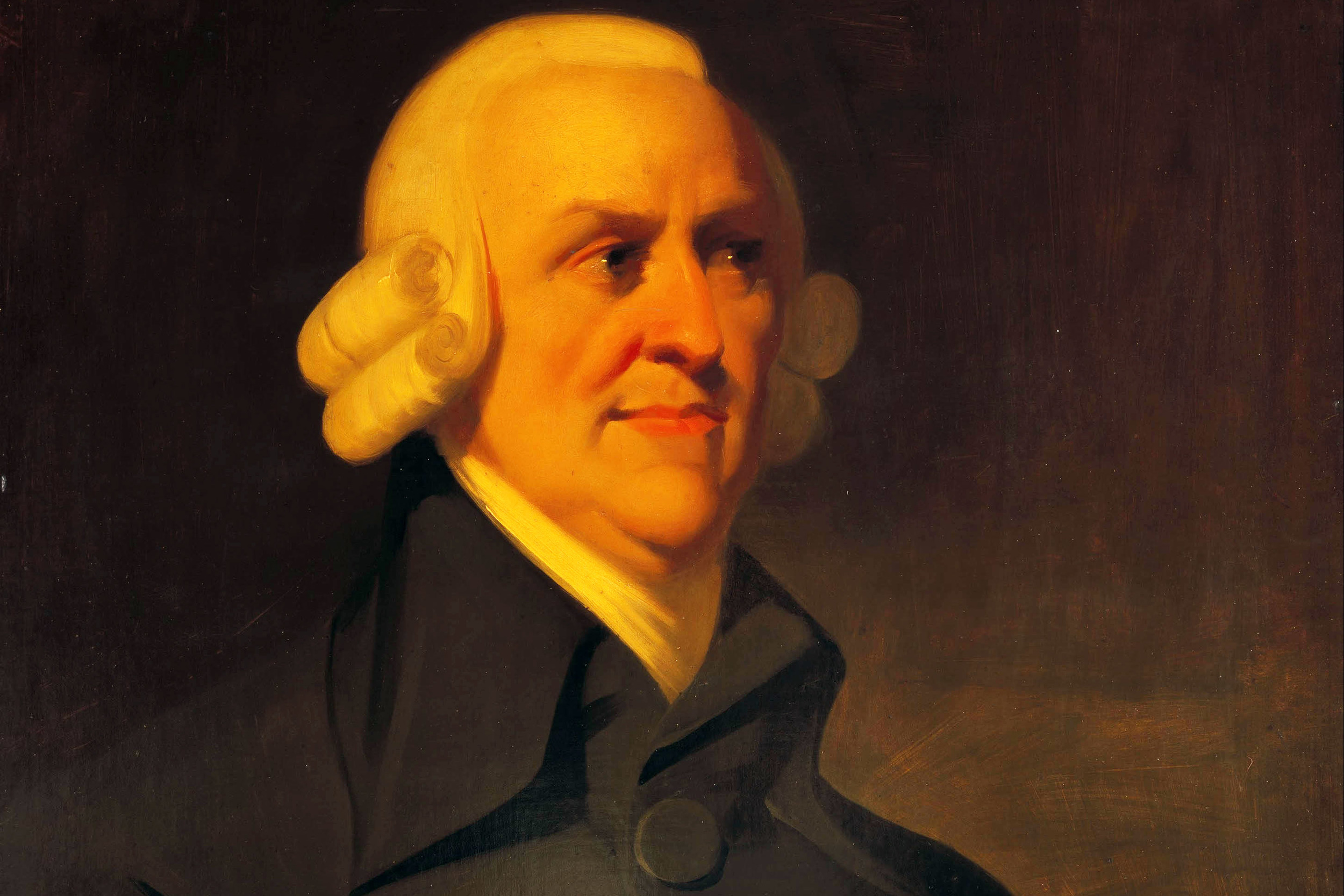

Happy 293rd birthday Adam Smith

It’s Adam Smith’s 293rd birthday. What would the pioneering Scottish economist, who in 1776 published The Wealth of Nations as a staunch defence of free trade, make of the world and its economic relations today?

At one level, he would be delighted. His free-trade message certainly got through to most of his fellow economists today. They share his view that trade benefits both sides – both buyers and sellers. After all, neither side would voluntarily strike a bargain unless they each thought it would make them better off. That is why Smith argued for ending Britain’s ‘beggar my neighbour’ policy, dropping trade barriers – a source of particular contention in the American colonies – and welcoming open trade with anyone who would reciprocate.

It’s Adam Smith’s 293rd birthday. What would the pioneering Scottish economist, who in 1776 published The Wealth of Nations as a staunch defence of free trade, make of the world and its economic relations today?

At one level, he would be delighted. His free-trade message certainly got through to most of his fellow economists today. They share his view that trade benefits both sides – both buyers and sellers. After all, neither side would voluntarily strike a bargain unless they each thought it would make them better off. That is why Smith argued for ending Britain’s ‘beggar my neighbour’ policy, dropping trade barriers – a source of particular contention in the American colonies – and welcoming open trade with anyone who would reciprocate.

And over the years, politicians too have heeded this economic message. So with a lot of pushing from the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) talks that preceded it, import tariffs – the taxes that countries impose on imports from others – have fallen all over the world. Smith would be delighted. And he would be particularly delighted by how the globalization created through such free trade has helped the poorest countries of the world more than anyone – taking perhaps two billion of the world’s population out of the most abject dollar-a-day poverty.

But Smith might cast his eye over the EU and the US – which account for 60% of world GDP, 33% of trade in goods and 42% of trade in services – and wonder whether the message has really sunk home. Tariffs may have fallen, but all kinds of non-tariff barriers – technical, regulatory, paperwork and administrative hurdles – remain, all designed specifically to protect domestic producers and keep out other people’s goods and services. Even in places where a ‘single market’ is supposed to exist – like the EU – it does not. Though the EU accepted the principle of a common market in services ten years ago, it is only very partially applied. Just try selling insurance or banking products in France and Germany. And this, of course, is a particular problem for the UK, which is home to the EU’s leading international financial services sector.

And again, while EU tariffs against other countries average just 3%, some discriminate massively against other, non-EU countries, including many of the world’s poorest. The UK’s once-prosperous sugar processing industry for example, is now a pale shadow of its former sense. The tariffs on non-EU sugar imports are just too high. And that has a particularly damaging impact on poorer countries where sugar can be just about the only cash crop.

Africa produces $2.4 billion worth of coffee each year – rather less than the Germans make from processing and re-selling it – but EU tariffs of 30% on processed cocoa products like chocolate or coco powder (and tariffs of 60% on some other cocoa products) are blatant discrimination. Not only does it mean that Africa sells less cocoa. It also means that there is less investment, innovation and technology going into the crop. So it keeps African cocoa farmers poor.

Added to which, Africa imports over 80% of its food; and the EU, with its highly protectionist agricultural policies and large clout in world markets, actually raises the price of food. Trade economist Professor Patrick Minford thinks the effect could easily be 10% or more. So not only does the EU keep out African agricultural products, it also forces Africans to pay higher prices for their food on world markets.

And Smith would also be worried about the mood that is developing in the US. Despite being relatively open to trade for half a century or more, the US has always been quick to protect certain industries – like steelmaking and auto manufacturing, for example. The result is that US steel- and car-makers have had too easy a time, have not innovated fast enough, and have been eclipsed by lower-cost providers in other countries.

President Obama has been lukewarm on trade freedom, opposing the Keystone pipeline and showing no support for dropping the prohibition on US crude oil exports. In the Presidential election campaign, meanwhile, the protectionist rhetoric has been ramping up. Republican front runner Donald Trump has advocated forcing US companies to ‘bring manufacturing home’ – that is, to stop outsourcing to other countries – and generally to tear up US trade agreements. His arguments have not faced much opposition: indeed, the Democrat hopeful Bernie Sanders agreed wholeheartedly with them. Democrat front runner Hillary Clinton, meanwhile has no clear stand on trade agreements, though she likes to pepper her speeches with digs about ‘hedge fund managers’ and ‘billionaire CEOs’ who are more interested in a buck than the health of the US workforce. And recent voting in Congress show that her party is becoming more protectionist.

Many of the other candidates, too, have opposed ‘fast track’ negotiation of the TPP trade agreement with Asian countries, which looks certain to be kicked into the longish grass of the next Administration. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) talks, meanwhile, are hitting the sand of protectionist demands from various of the EU’s 28 member states. (As is the EU’s proposed trade deal with China – bogged down by demands from Italian tomato growers and suchlike.)

As a big winner from globalization – think silicon valley, aircraft makers, pharma companies, the music and movie industries – the US has much to gain from focusing on the global market, and not just its domestic market. But will it keep its doors open to others, or is it going the way of Nigeria and Venezuela?

Smith was a quiet and modest man. But he would give both the US and the UK – not to mention Russia, China, India, Indonesia and all the other countries who have been raising trade barriers – a very stern talking to.

Eamonn Butler is Director of the Adam Smith Institute

Obviously, drugs drive you mad: for there must be regulation of them

We are half a step forward here on the subject of the legalisation of drugs. Part of the Millian thesis seems to be getting through, we should not ban behaviour which harms only the person undertaking that behaviour. Similarly, the pragmatic point that illegality doesn't in fact work has been understood. Sadly, the logical loop hasn't been completed for there's still a misunderstanding about regulation. The point being that there must be regulation, there must be regulation about everything.

Who does the regulating being the important thing:

All drugs should be decriminalised, Britain’s leading public health experts say ina landmark intervention today.

The law is failing to protect drug users or society and police involvement in drug-taking must end, according to the Royal Society for Public Health and the Faculty of Public Health.

The two bodies, which represent public health experts working for the NHS and councils, are the first leading medical organisations to come out in favour of radical drugs reform.

In their blueprint for an overhaul of Britain’s attitude to substances — ranging from class A drugs such as heroin and cocaine to cannabis and so-called legal highs — they argue that addiction must be regarded as a health problem rather than a crime.

Possessing drugs for personal use would no longer be punishable under the reforms but the health chiefs stop short of proposing that the state should regulate sales. Anyone making or dealing drugs would still face prosecution.

It's that last sentence which is the problem. There has to be some regulation of purity, concentration, strength and so on. And it's fine that the State doesn't do that. But we do still need to have regulation of those things - and that should be being done by the consumers.

By analogy with the past the great clean up of the food supply was in the latter half of the 19th century. And that clean up came not as a result of regulation by government - most of the egregious middle Victorian (or, if you prefer, early industrial age) abuses had already been dealt with by the market itself. Brands appeared, promising quality, and those that did so prospered, pushing out of the market the more adulterated offerings. An inverse Gresham's Law, good food pushes out bad. As an example, canning was in its early days and it was all too easy for those not very good at it to poison large numbers of people (badly canned fish has killed people through botulism poisoning in our own lifetimes). The brands that started and then survived to our own day, the Heinz, Campbell's sort of stuff, were rather more adept at not poisoning their customers than others.

And so it will be with legal drugs. As we say, it's just fine that the State won't be regulating purity or sourcing. But someone has to, somewhere, for there must be regulation and pressure upon suppliers,. And that can only be done if supply is legal so that consumers can indeed regulate through their behaviour - and, of course, the usual exigencies of tort and consumer law.

Legalising drug consumption is something we've been arguing for for decades. But along with that must come legalisation of supply. Only then can brands, reputations and a holding to account become possible.

That the regulation comes from "Which Drug?" with monthly publication of which brand is cutting with rat poison, which with brick dust and which is offering the actual drug in a reasonable state of purity is what will drive the dust and the poison out of the market. And that's why drug supply must be legal: because there must be regulation and that consumer choice is the most effective form there is.

Legalisation of drug consumption is a good idea but we'll only really have solved the problem when we can hold Bayer to account for the purity of its heroin by buying it or not buying it according to our perception of its quality. Which means that we must be able to identify the vendor and that means legality of supply.

One tax cut free marketeers shouldn't support

Milton Friedman once said “I am in favor of cutting taxes under any circumstance and for any excuse, for any reason, whenever it’s possible."

Now I try not to make it habit of disagreeing with Milton, but, following Sam Bowman's post on good and bad ways to do redistribution, I want to explain why I think free marketeers should oppose Vote Leave's recent proposal to scrap the 5% VAT on Household Gas and Electricity.

Currently the EU restricts the ability of member states to vary rates of VAT on different products like tampons or fuel. This is done to promote trade across the EU. Without this power, there's a risk that nations will exempt products that can be made cheaply at home and raise VAT on products that tend to be imported, creating tariffs by proxy.

But, even putting free trade to one side, there are good reasons to oppose exempting certain goods and services from VAT. Free marketeers know that flatter, simpler taxes are vital to encouraging growth and reducing unemployment, but tinkering around the edges with VAT exemptions takes us even further away from that goal.

There are better ways to help the poorest. Vote Leave argue that the 5% tax on household energy bills is regressive because the poorest spend three times as big of a proportion of their income on energy costs compared to the well-off. But if you're aim is to help those on low incomes, VAT exemptions are a staggeringly inefficient way of doing it.

Sticking with fuel. Let's look at who'd benefits. Someone living in a small flat will typically pay about £26 a year in VAT on fuel, but someone on a larger income living in a large house will pay £76. So while that extra £26 will certainly mean a lot to the someone living hand to mouth, you have to spend an extra £74 in handouts to relatively wealthy people to that £26.

In fact, the IFS ran the numbers and found that if you scrapped every single VAT exemption and replaced them with tax cuts for low paid workers (e.g. raising the personal tax free allowance) and increased means-tested benefits (e.g. Working Tax Credits), you could preserve the existing progressivity of the system and still raise an extra £3bn to fund further tax cuts or pay down the deficit. (Note: This was calculated when VAT was 17.5% rather than the current 20%, so this change would probably raise more revenue now, even more once you factor in growth and inflation.)

Exemptions distort consumer choices. By taxing some goods less than others, the state nudges consumers to spend more on certain goods and less on others. In the case of fuel, it might encourage people to leave their heating on, when otherwise they would have instead put an extra layer of clothing on. While such a case might seem small or trivial, if you add up every single VAT exemption and add it up across the economy, you end up with very large distortions and inefficiencies.

These distortions can also discourage innovation. Take the case of E-Cigarettes. They're taxed at the full whack of VAT while other highly regulated anti-smoking products like Nicotine patches and gum are taxed at 5%. At the margin, this gives less of an incentive for businesses to invest in e-cigs and more of an incentive for them to invest in nicotine gum.

They create unnecessary complexity, which encourages wasteful avoidance. Is a Jaffa Cake a biscuit or a cake? (Likewise is a burrito a sandwich?) A question that should have been left to philosophers, instead is brought into the courtroom. McVities fought a hard battle (and baked a massive Jaffa Cake) to prove that Jaffa Cakes are cakes and not biscuits, thus qualifying them for a lower rate of VAT. Again, the money wasted here might seem silly or trivial, but it adds up.

This is bad for two reasons. First, it's a misallocation of resources. Every pound McVities spend on tax lawyers is a pound they're not spending on investing in new products (although in the case of Jaffa Cakes maybe that's a good thing.)

Second, it can actually lead to worse products. Take the case of Cornish Pasties. In theory, hot prepared food should be taxed at the standard rate of VAT. Straightforward enough, but according to tax law, products that are incidentally hot (e.g. freshly baked bread) are not taxed at the standard rate and instead taxed at the same rate as cold groceries (if this weren't the case, bakers would have to wait till their bread had cooled down to avoid tax). So whether or not you end up paying a Pasty Tax depends on whether it's incidentally hot (i.e. it's just come out of the oven) or deliberately hot (it's been kept in a heated cabinet). At the margin, this encourages bakers to sell cold pasties when they could be selling hot ones.

Indeed the deeper you get, the more maddening it becomes.

I'll leave you with a puzzle.

Do I have to pay VAT on these Heart Shaped Marshmallows?

According to VAT Notice 701/14, edible cake decorations are zero-rated but marshmallows aren't. So what is it?