To think that people are complaining about this

It's true that America's Cheesecake Factory is not the sort of gourmet food consumed by refined aesthetes like you and we. But it's perfectly acceptable food for all that, rather better than average in fact. You also get a hefty portion for not all that much money. The puzzle though is that people complain about this:

Watch out, diners: There are serious calories in some restaurant meals.

That was the message of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a nutrition advocacy group, as it released its annual "Xtreme Eating Award" winners — the most calorie-stuffed dishes and drinks from the country's chain restaurants.

Topping the list were entrees like The Cheesecake Factory's Pasta Napoletana, which the chain describes as a meat lover's pizza in pasta form. The pasta, dressed in a Parmesan cream sauce, is topped with Italian sausage, pepperoni, meatballs, and bacon and clocks in at 2,310 calories, 79 grams of saturated fat, and 4,370 mg of sodium.

We checked the price of this and in the LA area it seems to come in at $14. At which point we really do start to wonder why people are complaining.

Our point being that there has never in human history been a time when the average working guy or gal could go and have a full day's worth of calories of meaty goodness - OK, we know that meatballs and sausage are made of the scrag ends but still - for two hours of minimum wage labour, or more pertinently around 30 minutes work at the US median hourly wage of $25. Not cooked in a restaurant there hasn't been a time before now when this was true.

Far from us complaining about this we'll just add it to our list of proofs that the Good Old Days are right now.

RPI is silly, but not completely crazy

Chris Giles, the FT's economics editor, has recently been waging a war on the retail prices index (RPI)—Britain's venerable price statistic used to set rail prices, student loans interest, and repayment of some gilts. I'm a fan of Chris, but I think he's gone a bit far: yes, RPI is a bad index, but no, it's not necessarily unfair and wrongheaded in the way he describes.

Nowadays, the official measure of inflation is the consumer prices index (CPI), which, unlike RPI, is designated a national statistic. It's what the Bank of England uses for the flexible inflation target its monetary policy is based around and it differs from RPI by using a much better aggregation method, a bigger and more broad-based sample, and excluding housing.

It's not a judgement call: it's just a better index, which is why more or less everything has switched over. But some things aren't. For some of them it's because they date backwards. For example, the government has long sold RPI-linked gilts—there are £407bn outstanding according to Giles—from which we impute the TIPS market forecast of inflation. For others, it's less obvious why they do.

Now Giles has one very good point. In 2010 the RPI formula was changed to measure certain goods (especially clothes) more wrongly. This inflates the index. This means that repayments to pre-2010 RPI-linked-gilt-holders are higher than they would otherwise have been. Whenever this move was expected—or if unexpected, announced—this was a handout to pre-2010 holders. But after that point, it's all priced in. Everyone knows the index will overestimate inflation, and everyone knows by about how much (any error benefits the govt as much as the investors). Yes, we shouldn't have done it, and maybe we should even claw this money back—but it was a once-off error. Market pricing means it doesn't compound.

But I don't follow his other points at all. Yes, RPI adds some arbitrary amount onto "true" inflation, so post-2012 RPI-linked student loan interest rates are higher than they would be with CPI. But the interest rate on these student loans is entirely arbitrary anyway. Given their repayment rates (around 55%) and repayment schedules, the government is clearly subsidising their true cost to an astonishing degree. The RPI link is a semi subtle way of getting a small portion of that back. Like how "money illusion" means unexpected inflation is good during slumps.

The same is true of rail fares. It's good that RPI hides a little bit of extra increase in real fares. Economising on scarce resources through prices is a good thing, and we currently subsidise rail somewhat too much. If we do it through explicit price increases, people might bear a larger psychological burden when we (slightly) reduce how much the government pays for people's rail travel.

Switching to the CPI doesn't magic up money. In both cases it just makes the government pay more, and the users of the service less. Does Giles really think that the baseline is inflation plus the arbitrary number they've currently set by fiat, rather than inflation plus that arbitrary number, plus the arbitrary chunk of measurement error? It's hard to see why.

This isn't to say that we shouldn't switch away from RPI. It's a bad stat, and if Chris is right about the legality of doing so, then it sounds like we could quite easily switch, eventually, without the large reputation costs that go with seeming like we're reneging on obligations. But let's not use motivated reasoning to get there. And is it really necessary to use language like "fleecing", or blame the ONS, who almost certainly are not the ones making the final judgement call?

Market values and the stress tests

This blog posting is the first in a series on the 2016 Bank of England stress tests. A fuller report, “No Stress III: the Flaws in the Bank of England’s 2016 Stress Tests”, will be published later in the year by the Adam Smith Institute.

This blog posting is the first in a series on the 2016 Bank of England stress tests. A fuller report, “No Stress III: the Flaws in the Bank of England’s 2016 Stress Tests”, will be published later in the year by the Adam Smith Institute.

Early in January this year, ITN’s Joel Hills approached me about a feature on the stress tests that he was planning to do for News at Ten, and which was broadcast on January 10th. He was going to interview Sir John Vickers on the market values vs. book values issue and he asked me if I would provide the results that showed how using the latest available market values instead of book values would have affected the results of the Bank’s 2016 stress tests. Sir John and I had been arguing for some time that the Bank should pay more attention to market values, especially when they are lower than book values: as of early January 2017, market values were about 2/3 of book values.

The choice of book vs. market values makes a big difference to the results of the stress test: if you use book values in the Bank’s stress test, then only RBS fails the test, but if you replace book values by market values and make no other changes to the test, then only Lloyds passes. So book vs. market values is a big deal.

Why should we use market values rather than book values? The reason is that market values being less than book values signals that the markets do not believe the book values: the most likely explanation is that the markets believe that there are expected losses coming through that the book values are not picking up.

Vickers had put a similar point to Carney in a letter of December 5th last year:

… market-to-book ratios for some major UK banks are well below 1. That indicates market doubt about the accuracy of book measures. To the extent that such doubts are correct, stress tests based on book values are undermined.

The Bank appears to take the view that low market-to-book ratios are down to dimmed prospects of future profitability rather than problems with current asset books. But such a view is hard to sustain for banks with [price-to-book] ratios below 1. There is, at the very least, a serious possibility that low market-to-book ratios are signalling underlying problems with book values. This certainly cannot be dismissed, especially when one is examining the ability of the system to bear stress – an exercise that calls for prudence. [1]

To me this statement is self-evidently correct, so I was surprised that in his reply letter Governor Carney sought to challenge it: he continued to defend the Bank’s earlier position that low market-to-book is due to low future profitability and dismissed Vickers’ concerns about the possibility that markets might be signalling deeper issues with the book values.

I have to ask myself how the Bank of England can be so sure (and prudently so!) that its interpretation is correct and that Vickers’ is not.

Vickers’ March 3rd response to Carney’s dismissal of his analysis is unanswerable:

The regulation of banks is based on accounting measures of capital. A major source of risk to financial stability is that capital is mis-measured by the accounting standards used in regulation. In that case, bank regulation that allows high (e.g. 25 times) leverage relative to accounting (or ‘book’) measures of capital is more fragile than may appear.

An instance of this point is that stress tests based on book values are themselves vulnerable to erroneous measurement of capital, because those measurements are their starting point. Furthermore, bank regulation nowadays counts convertible debt instruments such as CoCos as akin to equity capital, but the conditions in which they convert to common equity (or are written down) are also dependent on accounting measures of capital. In short, a lot is riding on book values being reasonably accurate. …

None of this is to say that markets necessarily value assets accurately. Rather, the point is that low price-to-book ratios, especially when below one, signal a serious possibility that book values are inaccurate, and hence that the basis for regulation (not just in stress tests) is open to question.

Market values are not always reliable, but

when [market values] are low, systematic attention should be paid to them, and transparently so. [2](My italics)

More clutching at straws: further BoE arguments against market values

Let’s consider another objection made by the Bank against it using market values:

Low market valuations can reflect a number of things, all of which lead to weak expected profitability. But, crucially, different reasons for weak profitability can have quite different implications for a bank’s resilience. This is because they have different impacts on the value of the bank’s assets if it needed to sell them to pay for losses elsewhere in the business. [3]

The Bank then illustrated this point by comparing two hypothetical banks with the same cash flows – one is efficient but has poor assets, the other is inefficient but has good assets and could sell some if need be.

The Bank’s argument is a distinction without a difference, however. Weak expected profitability – whatever the cause – is a potentially serious financial stability issue and it is as basic as that. As Vickers pointed out in his April 26th letter to Alex Brazier:

A holder of the BoE view, if I may put it that way, can however respond by noting … that the inefficient bank with good assets can sell some. If such a bank alone faced difficulties – so in the absence of systemic stress – this would be a reasonable answer.

But it is harder to see how asset sales could be a satisfactory response in conditions of systemic stress, a typical feature of which is precisely the inability of banks to sell assets except at distressed prices. This is the well-known ‘fire sale’ problem …

The gist of this problem that a bank that suffers a large loss might be forced to reduce its asset holdings by selling assets at fire-sale prices. If other banks must revalue their assets at these temporarily low market values, then the first sale can set off a cascade of fire sales that inflicts losses on many institutions and thereby create asystemic problem.

This kind of risk, I suggest, should be central to thinking about financial stability, and to stress tests. Financial stability policy should take a prudent approach as a general matter. In particular, it should not place reliance on banks being able to sell assets in crises at good prices. While that might cope with an idiosyncratic shock affecting one bank, it will not do in a systemic crisis. But systemic crisis risk is the principal risk that regulation should guard against. The prudent stress test question, then, is whether the bank can meet its obligations without resorting to asset sales. It is not whether it can do so on the assumption that assets can be sold at good prices.

In sum, low market valuations imply less resilience even when the possibility of asset sales is allowed for. Tests of resilience that rely on resort to asset sales are flawed because, as experience shows, in a systemic crisis it may well be impossible to realise full value from asset sales.

Tim Bush also offers a powerful rebuttal:

Essentially, from the perspective of a shareholder providing capital, the Bank’s second example (good current balance sheet, poor future returns) is really an admission that a bank as a whole is one big impaired asset. Nothing resilient about that. Particularly, no incentive to refinance it if it incurs unexpected losses for example. New investment won't achieve an appropriate return.

The Bank’s line is a bit like saying British Leyland was resilient if the factories were brand new. [4]

Another objection to the use of market values was made by Alex Brazier in his evidence to the Treasury Committee on January 11th 2017:

…if you had [relied on market cap values] before the crisis, you would have been led completely astray … You would have been led to the conclusion that the British banking system was remarkably resilient, and, as forecasting errors go, that would have been quite a good one. [5]

Really? Consider this chart, which shows how the price-to-book (P2B) ratios of international banks fell the before crisis. The P2B ratios for UK banks are similar.

Then consider the next chart, which shows the ratios of market capitalisation to the book value of equity for two sets of international banks, the “crisis” ones that failed, required assistance or were taken over in distressed conditions, and the “non-crisis” ones that weathered the storm.

It is, thus, clear that markets were signalling problems with the banks and they correctly identified the weakest banks too. In the UK case, they also correctly identified in advance the two biggest UK problem banks, HBOS and RBS. [6]

Mr. Brazier omits to mention that the Bank was relying on Basel model-based book values that completely missed the impending meltdown and he does not offer any alternative that would have credibly worked better.

He also omits to mention the Bank’s own record on this issue. The ‘British banking system is resilient’ is exactly the message that the Bank itself was putting out before the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Not only did the Bank itself have no inkling of the GFC before it hit, but in the early stages of the GFC and even after the run on Northern Rock, it was still reassuring us that there was little to worry about and that the UK banking system was more than adequately capitalised. These reassurances proved to be as wrong as wrong can be.

The charts above are evidence that market values did provide some warning and there is further evidence too. To quote the Bank’s own chief economist, Andy Haldane:

market-based measures of capital offered clear advance signals of impending distress. … Replacing the book value of capital with its market value lowers errors by a half, often much more. Market values provide both fewer false positives and more reliable advance warnings of future banking distress.

… market-based solvency metrics perform creditably against first principles: they appear to offer the potential for simple, timely and robust control of a complex financial web. [7]

It is also helpful to compare their respective track records at predicting subsequently realised bank failures: markets have sometimes got it right and sometimes got it wrong, but bank regulators have always got it wrong. Their failure prediction rate is exactly zero percent. Even chicken entrails would have had a better success rate than whatever model or crystal ball regulators anywhere use to peer into the future and no rational person would ever believe the forecasts of a group of forecasters with a zero percent success rate.

The former President and CEO of BB&T Bank, John Allison, confirms this point and explains why:

One observation in my 40-year career at BB&T: I don’t know a single time when federal regulators—primarily the FDIC—actually identified a significant bank failure in advance. Regulators are always the last ones to the party after everybody in the market (the other bankers) know something is going on. … regulators have a 100 percent failure rate. Indeed, in my experience, whenever they get involved with a bank that is struggling, they always make it worse—because they don’t know how to run a bank. [8]

But I digress.

So what it comes down to is that if the Bank does not use market values for the stress tests, then it should have a good reason not to. In terms of a concrete operating criterion, the natural answer is provided by the Principle of Prudence, which suggests that it should value using the lesser of book values and market values – and central bankers are famously prudent.

Whilst on the subject of prudence, wouldn’t it be wise for the Bank to acknowledge at least the possibility that outsiders – not just Vickers and I, but also Anat Admati, Tim Bush, James Ferguson and Gordon Kerr, to name a few, and even Mervyn King, who have pointedly failed to endorse the stress tests – might be right or that we might at least have a point?

So answer me this, Bank of England: you say that your stress tests show that the UK banking system is sound. But how can you be confident in such assertions, when your stress tests are based on book-value numbers and when the markets are clearly signalling that something is wrong with those book values?

To cut to the chase, how can you expect the public to believe your narrative when the markets don’t?

The Vickers proposal for parallel market and book value tests

So let me endorse Sir John’s suggestion for a compromise as set out in his December 5th letter. The Bank should present both sets of results and let readers make up their own minds. As he wrote:

[My] proposal is not that market-based tests for such banks should replace tests of the kind that the Bank has run. The request is merely that the Bank supplements its results with market-based results.

That would inform public debate on a matter of great importance for economic policy, and it would enhance the transparency and accountability of the Bank.

Yet the Bank still insists that it should not publish any such results because – to quote Governor Carney in his December 19th reply to Vickers’ letter – to do so might confuse

the Bank’s communication around its stress tests. If we publish two sets of results that give different messages, people might struggle to understand what we are trying to say about the resilience of the banking system.

But as Vickers responded:

A stress test is primarily a test of the resilience of the banks, not a communications exercise. …. Considerations of transparency and accountability should therefore far outweigh the regulator’s communications agenda. [9]

A related problem is that Dr. Carney takes the Bank’s credibility for granted and then focusses on making the message simple for the audience. Such reasoning puts the cart before the horse. Instead, the key to effective communication is credibility and credibility must be earned and maintained, not presumed.

The Bank does not help its own credibility by brushing aside good outside advice, however politely. Publishing market-based results could allay any possible concerns that it might be trying to window-dress the banking system and itself in the best possible light. The Bank would still be able to give its own commentary explaining why it thinks that the book-value results are more credible than the market-value results.

It is also a mistake for the Bank to under-estimate its intended audience, who should be presumed to be capable of making up their own minds when presented with the evidence and should be treated with appropriate respect.

The Bank repeatedly makes the mistake of ‘oversimplifying’ its message and then making claims that turn out later to have been way off the mark, thereby undermining its own credibility again and again. It made that mistake when it reassured us before the financial crisis that the banking system was strong. It made that mistake when it told us during the Brexit referendum campaign that a Leave vote could trigger a recession and that Brexit was the biggest single risk facing the UK economy, and it is making the same mistake again with the stress tests.

To paraphrase Hubert Humphrey on propaganda, a perhaps not entirely unrelated subject: the Bank of England message, to be effective, must be believed. To be believed, it must be credible. At the moment, it is not.

End Notes

[1] “Supplementary market-based stress test results,” letter from Sir John Vickers to Governor Mark Carney, December 5th 2016.

[2] Sir John Vickers, “Response to the Treasury Select Committee’s Capital Inquiry: Recovery and Resolution,” March 3rd 2017, pp. 7, 8 and 12.

[3] Quoted from Sir John Vickers’ letter to Alex Brazier, April 26th 2017, copies of which are available on request from Sir John.

[4] Personal correspondence.

[5] Treasury Committee “Oral evidence: Bank of England Financial Stability Reports,” HC 549, Wednesday 11 January 2017, answer to Q173.

[6] See, e.g., Chart 2.73 on p. 153 of the FCA/PRA report The Failure of HBOS plc.

[7] A. G. Haldane, “Capital discipline,” speech given at the American Economic Association, Denver, January 9th 2011, p. 8.

[8] J. Allison, “Market discipline beats regulatory discipline,” Cato Journal, 24(2), Spring-Summer 2014, p. 345.

[9] Quoted in Vickers Capital Enquiry testimony.

Our self-driving future is here... almost

In the past the idea of a driverless car would have featured in a science fiction movie rather than in companies’ plans for anything between the next six months to ten years. But automated vehicles are increasingly becoming less of a product of the imagination and more of a reality. By 2020, roads may look completely different.

In a sense, driverless cars are already here. In the summer of 2016, Uber began trialling them in Pittsburgh—although there were still two members of staff in the vehicles to make notes and step in if anything went wrong. Not that they needed to: the cars were mostly capable of navigating the city without human intervention.

We are very much still in trial stages, but some vehicle companies and their founders are confident of making great strides in the immediate future. Elon Musk, the creator of Tesla, said in April 2017 that by the “November or December of this year, we should be able to go from a parking lot in California to a parking lot in New York, no controls touched at any point during the entire journey”. Although he did clarify that the passenger would need to be able to intervene (so wouldn’t be able to fall asleep, for example), he predicted that Level 4 automated Tesla vehicles—where a car is driverless in almost all situations—would be available from 2019.

Google too have been involved in testing automated vehicles, with perhaps even more optimistic starting estimates than Tesla’s Elon Musk. In 2012, at which point Google’s driverless vehicles had already test-driven 300,000 miles, Sergey Brin said that “you can count on one hand the number of years it will take” for Google to have produced automated vehicles for the public. Although the technology behind the vehicles has not been finalised yet they have developed their automated vehicle project into an official company called Waymo as of December 2016. Chris Urmson, head of the project, has said that they are aiming to release the product by 2020.

Other car manufacturers are not so ambitious but are still making predictions that would see the introduction of entirely automated vehicles within the next five years. Nissan-Renault are looking to slowly increase the capacity of their cars to drive independently. Their aim for the ability to navigate a multi-lane highway by 2018, and complete automated ability in more complex driving situations such as urban environments, by 2020. BMW is working with Intel and Mobileye to create fully automated vehicles by 2021.

Even those that are cautious about the technology are working on ambitious timescales. The president of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety and the Highway Loss Data Institute, Adrian Lund, said in 2016 that he thought a Level 5 automated vehicles—the top level of automation, which would not require a driver under any circumstances—would be a minimum of 10 years away. A Level 4 vehicle could be managed within five, he thought.

Hyundai has also taken a slower approach: they are “targeting for the highway in 2020 and urban driving in 2030.” It is worth bearing in mind, however, that many later estimates make reference to Level 5 vehicles, while frequently earlier ones are for vehicles that have reached Level 4 of automation. Naturally timeframes are going to be longer if they are aiming for a higher level of technological advancement.

As things stand, the technology is still very much a work in progress, and accidents can and do happen. In May 2016, a trial drive of a Tesla ended in a fatality when “neither Autopilot nor the driver noticed the white side of the tractor trailer against a brightly lit sky, so the brake was not applied”. However, they did note that this was the first fatality of over 130 million miles of autopilot driving, whereas the world average is a fatality every 60 million miles.

Predicting the future is difficult. We cannot be sure exactly when autonomous vehicles will finally be here. But the best guess is we'll start seeing something serious in the next decade. Seeing as it typically takes fifteen years for the great majority of car owners to update their models, if manufacturers switch to only automated vehicles by 2030, it will still be at least 2045 by the time driverless cars completely dominate the road. While this may seem a while away, it seems as if ultimately, within many of our lifetimes, driverless cars will have a monopoly on roads across the globe.

Only one of these ideas on security of supply is correct

Jay Rayner tells us in The Observer that:

There is an imperative for Britain to become more self-sufficient, not for reasons of petty nationalism or to fulfil some agrarian fantasy of localism but because, without it, in the current political climate, we risk not being able to keep ourselves fed. There are a number of levers that can be pulled.

So therefore we must all pay more for Good British Food so that Good British Farmers can supply us in our greater self-sufficiency.

Also in The Observer, on the same day, a story about that other current green obsession, electric cars and the minerals with which to make their batteries:

Macquarie Research predicts that trouble in the DRC and rising demand for electric vehicles will lead to a four-year-long cobalt shortage. Writing in academic journal The Conversation, Ben McLellan, senior research fellow at Kyoto University, warned further: “Manufacturers such as electric vehicle makers should be concerned that the supply of one of the key mineral components, or the processing and refining infrastructure, could become too centralised in a single country. Without diverse source options, the possibility of supply restriction becomes more likely.”

It is of course the second of these ideas which is correct. Security of supply comes from having many sources of supply each enjoying, or suffering from, different sets of conditions. With minerals the thing to worry about is some feckless incompetent gaining political power and thus disrupting supply. With agricultural production that too matters - Zimbabwe is no longer the major maize exporter it once was - but we also have natural variability of weather. We want to be sourcing our food from as many different "weather areas" as we can.

Earlier in the year there was a lettuce shortage in the UK as Spanish weather disrupted the crop. Not a huge problem as other more expensive sativa could be supplied from elsewhere. But imagine the problems Spain would have had if they were attempting to produce all the food consumed there purely there?

This is not idle speculation either. The last incidences of true swollen belly children falling down dead famine in England were in Nothumberland and Cumbria just before the railway networks reached there. The reliance upon local food when the crop failed kills in the absence of the ability to acquire food elsewhere.

We agree entirely that security of supply of food is an excellent idea, as it is with minerals. But the solution with food is also as it is with minerals - many widely dispersed, subject to different conditions sources of supply. Self-sufficiency is the direct opposite of secure.

This is the way to protect the environment, buy it

Orri Vigfusson has a legitimate claim to being the saviour of the Atlantic salmon population. As his obituary points out:

The problem had begun, he said, in the 1950s, when the fishing industry discovered that salmon from rivers in North America and Europe gathered in the sea around Greenland and the Faroe Isles. A massive fishing operation was established, with thousands of miles of driftnets placed across the routes taken by the fish and the near destruction of the species.

Vigfússon realised that in the long run this was not sustainable and in 1989 set up the North Atlantic Salmon Fund with the aim of preserving and restoring those stocks. Using the wealth he had acquired from various business interests — including selling Icelandic vodka to the Russians — he bought up the fishing rights from trawler owners and others whose livelihoods had led to the depletion of the fish. The fund raised additional cash to support his work and over nearly three decades it has been able to buy and retire an estimated 85 per cent of commercial salmon quotas in the North Atlantic basin.

We have long insisted that fishing quotas should be exactly such transferable, monetisable, assets. Not despite these efforts rather because of them. No one needed to be dispossessed of their property of livelihood by law, we could and did leave it to the normal workings of the market. One of the driving economic forces here being the realisation that salmon fly fishing rights along rivers were worth more than the rights out to sea to those same salmon. Buying uot the one to protect the other thus made perfect economic sense.

He believed that commercial conservation agreements were better than intergovernmental treaties. “Why? Because if you don’t [follow the agreement], you don’t get paid,” he said. “Money talks.”

Quite so. There are many who hanker for a world in which this isn't true but we really do think it best to deal with humans as they are, not as we might wish them to be. Therefore, if you want to preserve the environment why not buy a bit of it then preserve it?

We really don't know very much, certainly not enough to plan

This point has of course been made before, even by the occasional person even more illustrious than we are. However, it does bear repeating, we just don't know very much about our world:

The Current Population Survey Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) is the source of the nation’s official household income and poverty statistics. In 2012, the CPS ASEC showed that median household income was $33,800 for householders aged 65 and over and the poverty rate was 9.1 percent for persons aged 65 and over. When we instead use an extensive array of administrative income records linked to the same CPS ASEC sample, we find that median household income was $44,400 (30 percent higher) and the poverty rate was just 6.9 percent. We demonstrate that large differences between survey and administrative record estimates are present within most demographic subgroups and are not easily explained by survey design features or processes such as imputation. Further, we show that the discrepancy is mainly attributable to underreporting of retirement income from defined benefit pensions and retirement account withdrawals.

Note that this is the US Census analysing their own numbers. And note how far out they are, an entire 30% of median income. On the basis that, you know, people lie about their income.

All of which is an excellent example of what Hayek was pointing out, we don't in fact have the information to be ab le to plan the economy in any meaningful manner. Here, what value all those plans to reduce elderly poverty when we're 30% out in our estimation of how much elderly poverty there actually is? And that's from the best figures available to government.

Our ability to change things is severely limited by our inability to know how things actually are.

We need to talk more about Venezuela

On Sunday, Venezuela will go to the polls to vote for representatives to a council that will start rewriting the country’s constitution. After four months of street protests, 100 people are thought to have been killed by the Maduro regime and there are serious questions being asked in Washington about the potential of a civil war breaking out.

But how we did we get here and why does it matter that yet another socialist regime has reached its inevitable conclusion of abject failure?

In short, it matters because Venezuela has been held up as a paradigm of what could be possible for socialism by the West’s leading leftist commentators.

As Kristian Niemietz at the IEA has catalogued the current leadership of the Labour Party in this country, as well as their supporters in the media, used to tout Venezuela as an inspiration to their cause. Only yesterday the Daily Mail revealed that Jeremy Corbyn praised Hugo Chavez and criticised the European Union as being a ‘barrier to building socialism and fighting capitalism’ in a phone call to Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro back in 2014. Owen Jones, George Monbiot, the Labour MP Richard Burgon and Corbyn’s director of communications Seumas Milne have all put pieces out in support of Chavez, Maduro and the Bolivarian socialist revolution - they’re strangely silent on the topic at the moment.

The policies that Venezuela has adopted - which the Labour Party’s leader used to praise and which have been argued for by their supporters - have left Venezuela in ruin.

Policies such as pegging the currency at levels staggeringly divergent from its real value, financing large increases in public spending through printing money, strong state subsidy and price controls of basic goods, rent controls, and a string of nationalisations have all taken their toll. For a while a high oil price was enough to paper over the cracks but eventually you have to face up to economic reality. Debt repayments started adding up, a persistent public sector deficit and commitments to spending programmes its political leaders don’t want to sacrifice have led to scenes akin to those seen at the end of the Soviet Union, with money printing causing high inflation.

Yesterday the inflation rate in Venezuela reached a record high annual rate of 844.22%.Our own inflation rate was at 2.6% last month.

With the rate back up that high Venezuela’s inflation became the 57th verified episode of hyperinflation (it has been added to the official Hanke-Krus World Hyperinflation Table). You have to have inflation of over 50% for a period greater than 30 days to be included - fortunately that’s rare but as we can see in Venezuela it’s not rare enough.

The value of the Bolivar (the currency of Venezuela) has collapsed. On the black market one US Dollar can get you 7,691 Bolivars. There are two official rates, which are strictly controlled by central authorities. The DIPRO rate is currently 10 Bolivars to the dollar, with the DICOM rate recently devalued to just over 2,000 Bolivars to every US Dollar. DIPRO is used for imports of goods like food and medication, social security pensions for Venezuelans abroad, imports for sports and culture and payments to Venezuelan students abroad. DICOM is used for everything else (including oil) and is auctioned.

When I was Venezuela in 2009 - very briefly - I was struck by the divergent nature of the place compared to their neighbours Colombia. You couldn’t use the cash machines because they required your Venezuelan registration number and the differences in official and unofficial currency exchange rates were very apparent (I paid nearly $90 for two sandwiches from Subway in the airport).

This is a country of 31 million men, women, and children who have had their lives ruined by two successive socialist presidents, in a place that sits on the largest oil reserves on the planet.

Medicines are running out and infant mortality has spiked 21% in a single year and is 45% higher than in 2013. Heart surgeons have conducted operations by the light of mobile phones as power cuts hit.

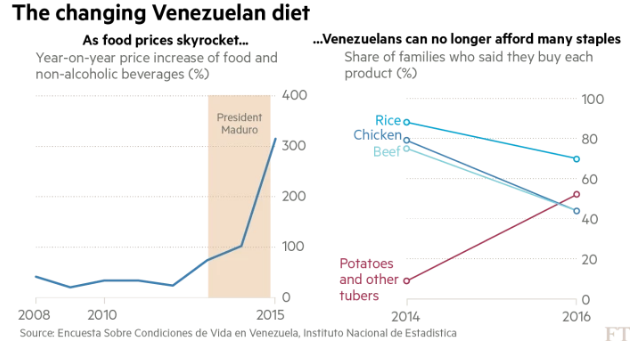

One of the most striking things that has happened is a change in people’s diets as inflation has skyrocketed and the Bolivar’s value has fallen, sapping their purchasing power. Consumption of staples that Venezuelan families had bought for decades began to fall as prices shot up. People stopped being able to afford things like rice, chicken and beef and have to replace these with cheaper and less nutritious crops like potatoes. Over 75% of the Venezuelan population say that they lost an average of 19lbs in 2016.

That’s before we mention the scary fact that Venezuela is fast approaching a crunch point. The country is down to its last $10bn of foreign reserves while the oil price is nowhere near the level of around $75 dollars the Latin American country needs to finance its public spending and debt commitments. State oil company PDVSA has $3.7bn of repayments to foreign creditors to make this year and another $8bn in 2018 - debts it needs to pay in order to keep any money coming in from oil exports.

The policies that Jeremy Corbyn has publicly praised as examples, that John McDonnell wants in order to start ‘fermenting the conditions to overthrow capitalism’, and that their media hands have been supporting for a decade are coming to their inevitable conclusion.

Venezuela deserved better than the economic hell its leaders have created. Venezuela is not an example that Britain should be looking to, but a warning. Those British journalists and politicians, including those leading Her Majesty’s loyal opposition, that lauded the socialist revolution should be looking again at their own policy suggestions.

This really is not poverty, to claim it is is to devalue the very concept

There is a certain tension over how we should be defining poverty. On the one hand we've Adam Smith's linen shirt example, if society thinks that not being able to afford something makes you poor, you cannot afford it, then you're poor in that society. On the other hand that declaration of poverty also brings with it, for all too many, the right to then confiscate from others to repair the deficiency.

Just about everyone agrees with both propositions but in differing degrees. We're just fine with the idea of that confiscation, that taxation, to produce food for the starving. We're likely to be less accommodating to a suggestion that something similar must be done about iPad inequality.

As so often with economic questions the answer becomes "It Depends."

At which point we really do need to insist that this isn't poverty:

A report from In Kind Direct says thousands of people are seeking help and describes the issue as a “hidden crisis”. Last year the charity distributed a record £20.2m of hygiene products, a rise of 67% on £12.1m the year before.

The charity itself looks like a thoroughly good idea to us. Manufacturers do end up with a certain amount of whatever that is off spec. Nothing wrong with it in its essence, just not quite up to prime time retailing - labels wonky, colours running on the printing, that sort of thing. Rather than dumping or scrapping it why not pass it along to the poor?

Quite, why not? And yet:

Growing numbers of people are facing hygiene poverty, where they are unable to afford essential products such as shampoo and deodorant, and are having to choose between eating and keeping clean, a charity has found.

No, we do not believe, and nothing will convince us to believe, that an inability to afford deodorant is poverty. And most certainly not the sort of poverty that lays a claim upon the incomes of others.

In fact, the very claim that this is poverty we would take as being evidence that there is no poverty in the United Kingdom today. Which puts us up there with Barbara Castle in fact, who back in the 1960s pointed out that there was no poverty in Britain any more. Both of us here talking about absolute poverty of course. There is still that inequality that some have more than others, still the possibility of Smith's linen shirt style as well.

But if that debate has now got to the point where we're talking about deodorant poverty then we're really very sure that the problem has been licked. What remains is a triviality of First World Problems level, something we can safely ignore while we get on with solving other matters.

Do Mediterranean search-and-rescue missions cause more drownings?

Earlier this week, a ship chartered by far-right activist group Defend Europe entered Mediterranean waters: apparently in a bid to support the Libyan Coast Guard's reconnaissance efforts, prevent human trafficking, and monitor humanitarian NGO activity. On its website, the group states that humanitarian NGOs are “responsible for the mass drowning of thousand [sic] of Africans in the Mediterranean.” The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimates that from the beginning of this year to the end of June, 2257 people have died or gone missing while trying to reach Europe by sea.

Defend Europe describe themselves as “Identitarian”: a label used by those who wish to preserve European culture by drastically cutting immigration and combating what they perceive to be Islamization. Although they claim to be partially motivated by preventing the suffering of migrants and refugees who drown attempting to cross the Mediterranean, they are at least honest about their primary goal. But immigration concerns notwithstanding, do those who claim that rescue missions incentivize dangerous Mediterranean crossings have a point? The key question here is whether the lives saved by SAR operations outweigh the lives lost as a consequence of irregular migration incentivized by them; the evidence suggests that they don’t.

One argument used to criticize the impact of SAR missions is that they increase the mortality risk of Mediterranean sea-crossings: independently of the overall number. An internal report from the European border agency Frontex, obtained last year by the Financial Times, argued that search-and-rescue (SAR) missions in the Mediterranean may incentivize riskier methods of smuggling. However, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)—one of several humanitarian organizations working in the area—have cast doubt on Frontex’s reasoning for this claim. Furthermore, Blaming the Rescuers—a report released last month by Forensic Oceanography—highlights more compelling explanations for changing smuggling practices in 2015-2016:

...the increasing involvement of militias in the smuggling business, the shift in composition of migrant nationalities, and the increasing interventions of the Libyan Coast Guard...have contributed to a downward spiral in the practices of smugglers and conditions of crossing over 2015 and 2016. The dynamics of Libyan smuggling are deeply shaped by the fragmented political landscape in Libya, which constitutes a causal factor in its own right. While difficult to measure, the influence of these trends on the increasing danger of the crossing in 2016 is undisputable. While Frontex has analysed smuggling networks in Libya, it has kept these factors out of the analysis of the causes of the deteriorating conditions of crossing offered to migrants, blaming them instead on SAR NGOs...

These criticisms stack up with recent analysis of mortality rates in relation to different periods of SAR activity:

The authors of this analysis also anticipate an objection to the use of Triton I mortality figures:

The high mortality rate during Triton I is largely the result of two large accidents on 13th and 18th April 2015, with estimated casualties of 400 and 750 people respectively. However, it would not be appropriate to consider these accidents outliers that were unrelated to the (absence of) SAR capacity. The excellent ‘Death by Rescue’ investigative report by the University of London’s Forensic Oceanography department analysed the circumstances of both accidents, using multiple sources such as photos, interviews with shipwreck survivors, rescue vessel crews, statistical data, GIS locations and internal reports by national authorities. It concluded that the deaths could have been prevented, had a more intensive SAR mission been in place...

The data referenced above casts doubt on the other main argument used by SAR-detractors, since it shows that migrant arrivals in Europe significantly increased despite the end of Mare Nostrum. Whilst it’s reasonable to assume that SAR operations may have some causal effect on irregular migration, the fact that arrivals were highest in the low-SAR period casts doubt on the strength of this effect and the likelihood that it outweighs the lives saved by SAR operations. Push-factors such as conflicts in Libya and Syria seem to have a far greater impact on the number of attempted sea-crossings than any pull-factors, as echoed in a 2015 International Organization for Migration report:

...the current migratory flows across the Mediterranean, from sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle-East to Europe, seem to be driven much more significantly by push factors that cause migrants to depart their homes, than by the pull factors that draw migrants to Europe.

I’m pessimistic about the possibility of self-styled Identitarians changing their mind about SAR missions in the Mediterranean on the basis of the available evidence. For them, the wellbeing of migrants and refugees is at best secondary to their misplaced concerns about the impacts of immigration. However, I’m hopeful that others—who understandably find the “pull-factor” explanation intuitively appealing—view this argument with a more critical eye.