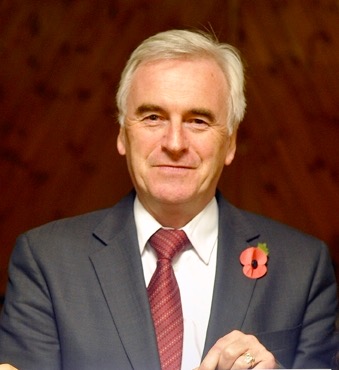

John McDonnell does really have to say this, doesn't he?

We're reminded of a bit of ancient history concerning scientific socialism here:

Britain is too obsessed with economic “growth for the sake of growth”, Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell has claimed.

High taxes and spending are part of the solution, he said, but cannot solve what he calls “fundamental” problems in the economy.

Redistribution only “made sense when the economy was growing and creating relatively secure, relatively well-paid work”, the shadow chancellor said.

He said the Government is “fixated” on economic growth and should instead shift its focus onto “decent, secure work... and combatting climate change”.

The old argument about the science of socialism was that it would be more efficient than capitalism and markets. Eliminate all that waste of competition and plan what is to be produced, by whom, where, and we'll all have more stuff. We'll be richer in short.

Then we went and tested the contention to destruction and 1989 showed that it was incorrect.

Oh well, not the first nor the last scientific or political proposition shown to be wrong. What's much more interesting is that the justification for the same policies has changed in this modern age. For all too many people still insist we should be doing those same things, they just trot out different reasons as to why we should. Some that it would be fairer that way, others even going so far as to insist that we shouldn't have economic growth therefore planning and socialism.

Which brings us to John McDonnell. He rather does have to say what he has, doesn't he? Objective reality shows that is proffered plans won't produce economic growth. Therefore he must insist that economic growth isn't what we're aiming for in the first place if he is to convince us of the righteousness of the plans.

We ourselves know what GDP, economic growth, really is. It's a rise in the value added in an economy. That, in turn, simply increases the potential for doing whatever it is that we wish to do. Whether you want more redistribution, more spending upon less pollution, less animal cruelty, better housing, schools capable of teaching pupils, really, whatever your list of what the good life is a larger economy increases the ability to produce or provide those very things. Thus switching the goal in favour of other targets doesn't work - we're still made better off by higher GDP even if we might argue about how that extra value should be deployed.

What we do when we're richer is arguable, but being richer isn't some thing to abjure in favour of what we might want to argue about.

Objecting to Objections to NGDP Targeting

Russell Lynch, writing in the Evening Standard, has raised two standard objections to NGDP targets, and they are valid concerns.

"One advantage of the current regime is that it is broadly understandable to Joe Public, who’ll most likely grasp Mandarin before nominal GDP."

I sympathise with this point and have previously advocated replacing the CPI target with a CPIH to bring the UK in line with other European countries. But at some point we should take a step back and ask whether using less bad inflation proxies is enough.

A clear upside of inflation targeting is the ease of communication but this is partly a function of the significant resources that the Bank of England devote to PR. Their schools outreach focuses on “Target 2.0” and this was introduced as part of a swathe of measures to educate the public. The reason there’s so much public attention is because that’s the chosen target.

I’m sure that “inflation” means more to Joe Public than NGDP. But this backfires when Joe Public sees a disjoint between the wage growth experienced, booming asset price boom, and an oscillating CPI measure that the Bank increasingly ignores. If the Bank were really committed to signalling to the public that the 2% target is sincere there would have been a lot more changes in policy since 2008. Ironically the stability praised by commentators is in part a result of ignoring the remit.

"Second, the benchmark is only as good as the figures on which it is based, which are less frequent than inflation data and prone to revision."

This point neglects the scale of opportunity from switching to an NGDP target. Data revisions matter most when policy is driven by the discretion of policy makers. But part of the argument for abandoning the present regime is to reduce the burden on decision making. The reason the paper discusses prediction markets is to introduce mechanisms that incorporate the collective wisdom of the market. My preferred NGDP regime would be a level target focusing on NGDP expectations. This would be forward looking and less prone to past revisions. But more importantly it would dispense with the monthly meetings where decisions get made. Monetary policy would be continually tied to a fixed nominal target and we could dispense with the apparatus of the chattering news junkies.

Here's that pesky environmental Kuznets Curve again

We don't have to go far to find people telling us that China's gross pollution is the future fate of us all. Capitalism and development lead to air that chokes, water that poisons.

And that just isn't how it works at all now, is it? That gross pollution, like our own Industrial Age, is a stage which is passed through. A simple and useful description of the point being this about China's very pollution:

“In the past, we made money first and could only talk about the environment later. But it’s clear the government has changed its mind,” he said. “We can see everything is starting to move in the right direction.”

That's simply what happens. When the alternative to straining every sinew to make a living is not to live then the environment gets very short shrift. At some point in development that luxury good (this is a technical term, it means we spend more of our rising incomes upon it, not that it is a luxury in the colloquial sense) of clean air gets the attention it might deserve.

This is simply an observation of how the world works, not something we say either should or must be. It's just that every society which has developed has done this as it develops. We've no reason at all to think that this won't be true of China, India, Bangladesh and the others too.

The real importance of the observation is that we shouldn't be spending heavily on that clean environment when such diversion from merely making a living does actually kill people. The lesson being don't become Greenpeace too soon.

IVF is the final frontier of capitalism?

It is possible, we suppose - if you squint very hard and define yourself carefully - to insist that in-vitro fertilisation is indeed that final stage of capitalism. That's not the way we think this is being said:

Kennedy recalled going in for treatment in a state of “blind panic and emotional chaos”, which she said was common for most people.

“It is a very charged time and I came out of the experience feeling brutalised. It was nothing physical, it was the attitude of the private sector … It felt like it was all about money,” she said. “It is the privatisation of reproduction, the final frontier of capitalism.”

We're really pretty certain that reproduction has been, over time, something of a private matter. In fact, the only time it has really been a public matter - in the sense of state governance of it, not social approval of different methods - has been when the eugenecists started to prevent the poor, feeble minded and generally, by their lights, undesirables from reproducing. Other than that we've all rather let people who wish to make the two backed beast get on with it, haven't we? Including the insistence that it is a private decision to bring any result to term or not.

We'd also, just because we enjoy being snide, note that the Medical Research Council refused to fund that research into IVF itself.

Reproduction as a private sector activity does seem to us to be fairly well established as the norm in human society.

But then we squint a bit and define ourselves carefully. Before 1978 those infertile - in some manners at least - had no chance of having children. Some parts of their current ability to do so have been, we'll agree, state funded and or provided. But it is only this roughly capitalist, roughly market based, socio-economic system which has led to a level of technology which provides that new found ability for them to be fecund. So if you want to call this, that the childless can become with child, a final frontier of capitalism we'll accept that. As long as you're using the same definitions we are.

What bliss it is in this dawn to be alive, eh? As some 5 million people born using the treatment are able to say.

Corbyn's thinly veiled threat to the press should worry us all

Yesterday the Labour leader posted a video to his social media accounts. Dogged for days by accusations he was complicit in passing information in multiple meetings to the Cold War Czechoslovak agent Jan Sarkocy, and having dodged questions on the topic by the press, Corbyn (or Agent Cob as the Statni Bezoecnost called him) decided he would not answer the questions but attack the press that were asking them.

It makes for a chilling watch. Singling out The Sun, The Mail, The Telegraph, and The Express, the Labour leader accused them of having gone ‘a bit James Bond’ over the issue. Let’s leave aside the fact that James Bond was the good guy (it was the Reds that were the enemy Jeremy), the video was full of inconsistencies.

As Daniel Finkelstein said in his excellent piece this morning on Corbyn’s on-the-record about the Cold War and the West, either the accurate reporting of Corbyn’s positions are fine or they are smears. If they are smears then why does he hold these views?

Corbyn’s claim that “a free press is essential for democracy” was accompanied by a thinly veiled threat to the owners of Britain’s media companies: “we’ve got news for them – change is coming”. This attack is one that deserves careful examination. He doesn’t just mean that social media is on the rise, but that he wants to change the balance between political actors and the press as it is.

His accusation that our press at present isn’t “very free at all” because organisations are owned by private individuals is concerning. There is little to no barrier to entry for a media organisation in this country. Ask any freelancer and they’ll tell you that the saturated market, disruptive new technologies and the vocation of the job is what keeps wages low and the market tight. But new media organisations come into being all the time and they live and die by their profitability. The Spectator, Economist and Private Eye all saw increases in their print runs and profits up with a mix of old and new media (as well as varied editorial positions), while in 2017 Buzzfeed made a £3.4m loss and the Guardian lost £44.7m.

The Labour leader is right that disruption is changing the media industry, but this isn’t really new. The printing press challenged the power of the Church, newspapers took on vested interests in politics and business, radio brought voices directly into homes and TV brought live images. Now we live with social media that demands quick responses as well as democratised questioning and accountability. But to pretend the old media doesn’t exist or have a role—to avoid the professional questioning because it makes you uncomfortable—is to act as though you’re untouchable. That route is well-trodden and it never ends well.

Corbyn’s position is also worryingly ignorant of the freedoms that all Britons have when it comes to dealing with accusations in press that you find to be libellous or defamatory. Both are criminal if the broadcast or printed words are found false. Our separate judiciary allows private citizens to sue and force them to prove their allegations, or to claim damages if they can’t. In many ways our libel laws are already overly burdensome. As my colleague Sam Dumitriu argued, investigative journalism is restricted by the high costs of lawsuits that mean settling is cheaper than fighting for truth. Not only is the actual cost a deterrent but potential cost means a more wary attitude of reporting. Along with super-injunctions, these laws are used by the rich and the powerful to mask activities they don’t want the public to know about. Corbyn’s response smacks of this, rather than the good work of the Index on Censorship that suggested reforms of a cap on damages that would still see the ordinary public protected against libellous of defamatory stories.

It should worry us all that Labour’s leadership is so emotionally triggered as to publicly attack the newspapers we read, the media organisations we watch, when they confront them with allegations Corbyn dislikes. We should heavily scrutinise the suggestions they put forward in the coming days as they back up the claim that ‘change is coming’.

The first of these has already appeared and it’s pretty bad news. Andrew Gwynne told the Daily Politics today that Labour were thinking of implementing a ban on foreign ownership of the press if they got to power. Labour need to decide their thinking on migration and economic nationalism. Is it just the press they don’t trust foreigners with? Is it just the rich ones they don’t like?

It’s going to be even more important that the press stands up for itself and that we continue to defend its scrutinising role after the Lords voted to press the government to set up Leveson 2 (the further public inquiry into the press that I’ve argued against before as uncompetitive and vindictive).

The press should stick to their watchword when dealing with these moves to restrict their freedom: print with neither fear nor favour.

Collective agreements see the rot setting into Denmark's dentists

Dentist care is one of the few things Danes actually have to pay for (or adults have to at least). This might puzzle you, after all Denmark is well known around the world for its free healthcare. In fact, it puzzles many Danes as well. However, the fact that Danes have to pay for it isn’t really the core of the problem - the concern is that it’s so gosh darn expensive.

Take my mother for instance. She is due to have two crowns inserted. If she is to have it done in Denmark the price would add up to £1400. Luckily, my parents live near the Danish/German Border, so she’ll be able to have it done in Germany for just the half of the price - and she is not the only one who does this. Many other Danes does this too - even if they have to drive for 3 hours. But the fact of the matter is that it doesn’t have to be like this.

Children's dental care is paid by the state, but once you reach the age of majority you have to pay for yourself (although approximately 20% of your trip to the dentist is subsidised by the region). While prices to a large extent are decided by free market forces in the rest of the Nordic countries, prices in Denmark are set by collective agreement between dentists and regional politicians with several downsides to it.

The fact that a wide range of services are set by collective agreements means that dentists can’t compete on prices and provide discounts in order to attract more patients. However, it is stated specifically in the collective agreement that this only applies when dentists accept the subsidy. Surely if they don’t accept the subsidy, clinics are allowed to determine the price themselves, right?

That’s not the case, unfortunately. Landssamarbejdsudvalget (try saying that three times after a couple of shots of Aquavit),a complaint board with the competence of interpreting the collective agreement for dental care, have over several rounds uttered that dentists can’t provide discounts. This is even if they abstain from accepting the subsidy from the region.

Different dentist chains have still tried to, however. In one instance the dentist chain Godt Smil offered free check-ups for patients who hadn’t been to the dentist. A clinic, PLUS1, gave discounts on different services whose prices were determined by the collective agreement. However, in return they abstained from the subsidy which in theory would have been in compliance with the agreement. Overall, they managed to cut the price on one of their package deals by 82%. Keep in mind some of that saving is the public subsidy. Nevertheless, Landssamarbejdsudvalget still deemed it in contravention of the agreement. In taking on the Landssamarbejdsudvalget the dentist chains had bitten off more than they could chew.

The collective agreement also stipulates certain restrictions on ownership of dental clinics. These include owning more than two clinics and people who aren’t licensed dentists having a majority stake in a chain. A dentist has to seek permission from the regional complaint board to open more than two clinics. Conflict of interest may also arise because of the structure of the complaint board. The board consists of 3 dentists and 3 representatives from the region. Half of the members of the board can therefore potentially be competitors to the dentist seeking permission. Because the board have to decide unanimously, competitors can veto the decision.

A similar situation was seen in North Dakota, USA where the Dental Board, mainly elected by dentists themselves, regulates the profession. In 2006 the board tried to stop beauticians and hygienists from whitening customers teeth because they thought they were undercutting dentists in price. Luckily, the Federal Trade Committee objected and in 2015 the Supreme Court put an end to the anti-competitive moves.

People understandably call for government to step in because they are under the impression that markets can’t live up to the expectations they have for important parts of the health sectors such as dental care. Little do they know, the root of the problem lies with government regulation, not the market.

In fact, the Competition and Consumer Autority have said that parts of the collective agreement are ‘straight up illegal’. Unfortunately, the Competition and Consumer Authorities can’t process some of the anti-competitive elements in the agreement because the Ministry for Health has assessed that price and ownership relationships are a necessary consequence of regulations on the health area.

If anything is to be done to secure suitable prices while maintaining quality in dental care in Denmark, it will have to take on the collective bargaining review that begins this year. The Ministry first of all ought to differentiate the agreement from law. This would leave it up to the parties taking part in the bargaining to give clinics the opportunity to compete on prices as well as opening up the market to new foreign competitors.

Secondly, successful dentists who want to expand their business should be able to do so. This would enable them to take advantage of economies of scale. In addition, the restriction of ownership - i.e. a majority of a dental company has to be owned by dentists - hinder the possibility of professionalising the dental industry and learning from best practices elsewhere. Opening up to equity funds and private investors would allow those who already have a general experience with business operations to develop an efficient business with chances of enhanced productivity.

Allowing the market to flourish would provide the consumer with cheaper dental care of higher quality and save the regions pointless expenses.

The basic problem with foreign aid

One of the slightly odd things about the modern world is that we've all become rather better at emergency aid and rather worse at development aid.

Emergency aid now tends to work with the grain of the economy. For example, in times of famine send in money - then let the market, incentivised by the cash, deliver the food. Instead of the ridiculous idea of loading ships with food which takes 8 months and more to arrive, neatly not feeding the starving but still destroying the market for the next crop.

Development aid is more often than not the application of those policies which we've rejected at home. Planned economies, for all the nonsense spouted by the likes of Momentum, are rather out of fashion in the rich countries. So all those who would play with the lives of others by telling them what to do are off in the aid agencies.

Yes, certainly, we exaggerate, but not by all that much. Oxfam these days insists upon peasant farming as the long term solution for Africa's ailments, just as one example. Fortunately, officialdom is realising this error:

Foreign aid risks making Third World countries dependent on handouts by prioritising “short-term and immediate results” instead of “lasting change”, an official review warns.

The Independent Commission for Aid Impact warns: “The Department for International Development’s results system is not currently oriented towards measuring or reporting on long-term transformative change – that is, the contribution of UK aid to catalysing wider development processes, such as enhancing the ability of its partner countries to finance and lead their own development.

One way of putting this is that we should be aiding them to do things themselves, not doing things for them. Instructing, say, on institutions - the tolerable rule of law, reasonable taxes - and even paying for such if necessary. Rather than telling them where to put the steel plant they don't need nor want.

At which point a modest proposal. The official development aid budget is some £11 billion a year we believe. Almost all of what is spent upon development, rather than emergencies, being wasted (Ethiopia's Spice Girls comes to mind). So, why don't we not waste it?

We know very well what has caused the largest reduction in absolute poverty in the history of our species, this neoliberal globalisation of the past 40 years. Trade, not aid, that is. So, let us trade more.

We declare unilateral free trade to the world. This benefits us in aggregate, benefits the poor out there individually and in aggregate. But there are those here at home who would lose from it. Those currently protected by our own import barriers to such trade. It's also a standard part of economic thought that when an overall increase in wealth is possible, as free trade would bring, it is possible for those who gain to compensate those who lose leaving all truly better off.

Excellent. We use that currently wasted foreign development budget to compensate (through retraining perhaps, that sort of thing) those at home who would lose. We combine the most effective poverty reduction program known, that neoliberal free trade thing, with not wasting the development budget and compensating those few who would lose from this most efficient of all possible plans.

The only problem is that it seems to be politically impossible. But then that's not stopped us in the past if we're honest about it.

Why do neoliberals support a Negative Income Tax?

This morning, I spoke at the LSE’s Citizen's Basic Income Day on the neoliberal case for a basic income (or ideally a Negative Income Tax). I’ll be tweaking the presentation for our regular sixth form seminars, but below is an approximation of my remarks (thanks to our former Executive Director Sam Bowman for laying the groundwork):

Neoliberals support an efficient welfare state that guarantees a minimum standard of living for every citizen: ensuring that wealth created by globalisation and automation is spread across society. The design of that welfare state should avoid poverty traps created by high and inconsistent marginal tax rates: some people on Universal Credit only keep 20p of every extra £1 they earn (although this is still an improvement on previous marginal effective tax rates of up to 95p per £1). It should also be minimally paternalistic, which means as little means-testing as possible and delivery in the form of cash/bank account payments rather than funds that can only be spent on certain goods or services (e.g. housing benefit, food stamps). Finally, it should be a comprehensive overhaul of all benefits (including housing benefit), with the exception of disability benefits.

Following in the footsteps of Milton Friedman, we therefore support a Negative Income Tax (NIT) paid to individuals (including children) with a fairly low, uniform withdrawal rate. The base amount for the NIT should be set high enough to ensure a basic standard of living, with econometricians using experimental data to help determine the exact level of base payment and withdrawal rate.

We plump for a Negative Income Tax over the (very similar) Citizen’s Basic Income (CBI) option, although we would still support the latter if it were the only proposal on the table. While NIT claws back money from higher earners by withdrawing payments as earnings increase, CBI does so through the existing system of taxation (i.e. after the initial lump sum is paid to everyone). The problem with CBI is that giving rich people money then taking it away again through taxation is inefficient: “when the government transfers money, it does so in a leaky bucket.”

A Negative Income Tax could also make it easier to implement other parts of the neoliberal agenda, such as phasing out the minimum wage, introducing a carbon tax, and auctioning off visas. Minimum wage laws aim to guarantee a basic standard of living for those in work, but economic evidence shows that they have disemployment effects and slow down job creation. A Negative Income Tax accomplishes the aim of minimum wage laws without killing jobs and gumming up the labour market, rendering such laws without justification. Carbon taxes—which aim to compensate for externalities generated by pollution—are currently extremely unpopular, but linking revenues to the base NIT level is one way of making them politically palatable. The same link could potentially be established for state revenues from a visa auction system, which would make the well-documented link between immigration and economic prosperity more obvious to people already living in this country.

There are many objections to Negative Income Tax (and Citizen’s Basic Income) from the left and the right. On the left, detractors worry that the system will subsidise employers paying below-subsistence wages, undermine wider socialist struggles, and have negative effects on marginalized groups like disabled people, parents of multiple children, and those with high housing costs.

On the first point, I defer to the Cato Institute’s Ryan Bourne discussing the similar case of tax credits: “employers generally pay people according to the productivity of their work, not some preordained amount to compensate them for a set standard of living.” While the experience of tax credits suggests that wages may drop slightly in the short-run as more people are encouraged to enter the labour market, this effect will quickly dissipate as the supply of labour adjusts accordingly. There’s also the oft-overlooked point that an income floor tends to increase the overall bargaining power of labour!

The claim that NIT/CBI will be used to justify more neoliberal policies at the expense of left-wing ones is partially true. But what this criticism overlooks is that a free market welfare system accomplishes what many on the left desire: poverty alleviation, increased worker bargaining power, and an end to (most) paternalistic means-testing.

Keeping disability benefits separate from the NIT/CBI addresses their potentially higher welfare needs, and targeting payments at individuals (including a rate for children) deals with varying family size. As for those facing high housing costs, it’s important to compare a Negative Income Tax with the failures of housing benefit (which should be abolished). Transition measures are necessary to avoid those receiving housing benefit being left in the lurch, but an equivalent cash payout as part of an NIT/CBI would encourage more efficient allocation of housing stock while stopping rents being hiked up. And of course, the best long-term solution to unaffordable housing is sweeping supply-side reform.

Opposition to Negative Income Tax from the right tends to focus on the purported cost, the potential for widespread idleness, and long-term political risks. It’s vital that cost is viewed in comparison to our current welfare system, and it’s important that those concerned with the overall size of the state remember that its scope also matters. That said, cost remains an open question that can only be decided by detailed analysis of any concrete proposal: like this one for an American system.

Even if it’s fiscally viable, doesn’t paying everyone an unconditional lump sum kill the incentive to work? Well, not really. Our recently released paper Basic Income Around The World looks at the evidence from Basic Income experiments and finds little evidence of workers exiting the labour market or significantly reducing hours worked: most reductions in the famous American and Canadian experiments were for time spent between jobs.

Perhaps the strongest objection I’ve come across from a centre-right perspective is the worry that any NIT/CBI would be ‘bid up’ and rendered harmful by the political process, as parties compete to offer the highest minimum level of income. As the Institute of Economic Affairs’ Steve Davies put it:

Given that, it is for many a racing certainty that it will be bid up by political competition to a damaging level and that there will also be constant and often successful efforts by special interests to create specific add-ons or separate benefits in addition to the UBI, which will lead to the re-creation of much of the existing welfare state but now in addition to a UBI. This will defeat the main point of a UBI for those who want to replace the costly complications of the existing welfare system.

The best answer I have here is that the future of any policy is uncertain, and any NIT/CBI could also be bid up or remain in rough equilibrium. More work needs to be done on the possibility of an independent political body (think of the Low Pay Commission or the Bank of England) taking responsibility for setting the details of such a policy out of the hands of politicians. In the end, the future of our welfare system is in our hands, and a Negative Income Tax should be the long-term goal.

Madsen Moment - BBC License Fee

This week's Madsen Moment sees Dr Pirie take on the BBC License Fee. Making up 10% of all prosecutions in England and Wales, as well as hitting the poorest hardest, the fee is outdated and indefensible. It's time to move to a subscription model.

Polly insists Tory NHS policy is working and working well

This is not, of course, what Polly Toynbee thinks she is saying yet it is still so. Her claim is that recent Cameron/Conservative policy concerning the National Health Service is working and working well:

After Brexit, David Cameron’s second worst legacy is his assault on the NHS. His explosive 2012 Health and Social Care Act was designed to privatise it into small pieces, while an eight-year funding droughtyields new worst ever figures every month. The wonder is that the service still treats so many so well. The number of GPs fell again last month, while graphs for nurses, emergency doctors, ambulance staff and just about everything show a relentless downward trend. Waiting times for cancer treatments rise, as do delays to treating older people’s hip fractures after falls.

The NHS is now the top cause of public anxiety, according to Ipsos Mori. Is there any good news? There is: the Institute for Fiscal Studies finds a continuing steep rise in NHS productivity, treating ever more people, far outstripping dismal overall UK productivity rates. Hold on to that fact,....

The grand problem with the NHS has always been that productivity. As many, including Polly, have told us it has its own inflation rate. 4% or so in fact. That is, unless the budget increases by that amount each year then there will be insufficient resources. Some of this is Baumol's Cost Disease - productivity is more difficult to increase in services than in manufacturing. But the cure to it, in so far as there is to something structural like that, is more markets, as it is in manufacturing and agriculture. Markets and competition are the causes of productivity increases. As someone as notable as Paul Krugman has pointed out, it's entirely possible that the entirely non-market Soviet economy managed not to increase total factor productivity one whit between 1917 and 1989.

We are not entirely on board with thinking that recent NHS policy has been perfect, to put it mildly. Yet the general gist, more internal markets, more competition, we approve of. And here we have Polly Toynbee no less telling us that it has been working.

Productivity in the NHS is increasing faster than in any other sector of the economy. No, don't wonder whether that is true, just consider the statement and the source. If it is true, as is stated, then that must, definitively, mean that recent NHS policy has been successful at dealing with the system's most glaring fault, the slower than the rest of the economy productivity growth.

And look at our source - Polly Toynbee. Good news, eh? It would be even better if she realised what is was she was saying....