What is the correct number of bank branches?

Lawyers are advised never to ask a question they don’t already know the answer to. We’re not lawyers so we can break this stricture with impunity and admit that we’ve absolutely no idea at all how many bank branches there should be across this green and pleasant land. We are certain how we find out, but the number is unknown to us.

Britain’s leading consumer group has called on banks to justify nearly 13,000 bank branch closures that have left millions of people struggling to access vital financial services across the UK.

Figures compiled by the consumer charity Which? show that the UK has lost nearly two-thirds of its bank and building society branches over the past 30 years, from 20,583 in 1988 to 7,586 today.

The loss of those sites has left 19% of the population more than nearly two miles away from their nearest branch, while 8% now have to travel more than three miles, with Scottish communities hardest hit by closures.

Which? obviously has in mind some level of service, or geographic distinction perhaps, which should determine that number. Our method is somewhat different.

How many bank branches are people willing to pay for? For quite obviously it is the people who use banks who pay for there to be banks to use. We’re not into the idea that we out here should be paying for other, perhaps richer, people to have somewhere safe to keep their money.

Once we’ve got that settled then the answer emerges. It costs money to keep a branch open, there’re rents, wages, rates to pay. If insufficient people use the branch to cover those costs then the branch should not be there. Expending more resources to produce something which is worth less than those resources used is a great way to make the society in general poorer.

So, how may bank branches should there be? Whatever number it is profitable to provide. Something that will change as technology does, as the society around the banking system does.

Seriously, how else could we possibly work this out?

Wider applications of the Kuznets Curve

Simon Kuznets, 1971 Nobel prizewinner in Economics, observed that as a nation develops, inequality usually increases until a certain level of prosperity is reached, then it declines. This is the so-called ‘Kuznets Curve,’ an inverted U-shape. It was not proposed as a universal law, just an empirical observation.

The Laffer Curve has a similar shape. Obviously with income tax at 0%, no revenue will be raised. Similarly, no revenue will be raised with income tax at 100%, because there will be no point to work. Between the two is a curve, which might have a point at which a tax rate will yield the greatest revenue. Many statists find this obvious fact unpleasant, preferring to believe that when income tax rates are raised, more revenue will be yielded. Practice suggest otherwise, that the inverted U-shaped curve has a maximum point, after which higher taxes yield less revenue.

Empirical observation suggests that pollution in countries increases as they develop economically. In the earlier stages they find it more important to avoid starvation than to have clean air and water. As they develop, however, they become wealthy enough to afford to produce more cleanly, and to look after their environment. Again, it is the inverted U-shaped curve. China polluted massively as it developed, and is now about at the point where if feels wealthy enough to redress that problem. On the whole it seems to be the rich countries that pollute less than the developing ones, because they can afford to do so.

Poor countries have had high fertility rates because many of those born do not survive infancy, and because children are needed to contribute economically, and later to support aged parents. Medical advances lower child mortality and enable people to live longer, increasing populations. As countries become richer, however, they can afford to put children into education instead of work, and can afford to care for retired people. Fertility rates decline in consequence. Many rich countries have birth rates too low to sustain population levels without immigration. Increases in world population are levelling off, and look set to decline after they reach 10bn, a far cry from the alarmist figures of 50bn suggested by some. Again, it is the familiar U-shaped curve identified by Kuznets.

Popper’s ‘conjecture and refutation’ in scientific discovery is mirrored in the market as some businesses are counted out when they cannot compete. Even the mutation and section of evolution follows a similar methodology, albeit without the inspired human brain behind it. The methodology of innovation and selective death rate seems to function in most aspects of human progress. This formed the basis of my doctorate in philosophy.

Observation suggests that the inverted U-shaped curve features far more widely than in the income inequality observed by Kuznets. It seems that in many cases of human development, the adverse consequences of it rise as it takes place, then level off and decrease when a certain stage of prosperity has been reached.

It provides an empirical counter to those who urge humanity to stop economic development, growth and technological advance. In many cases it seems that the adverse consequences can be overcome not by doing less of these things, but by doing more of them. In that way we acquire the wealth and expertise to solve our problems.

It's the decision making process itself which is wrong here

A reasonably fundamental question, set of questions, underlies this story. Who gets to decide and how to they reach that decision?

Coffee shop fatigue in a coastal town has resulted in a council blocking a new cafe from opening in a store left empty for a year.

Christchurch in Dorset had 14 coffee shops within a 500-metre stretch on its High Street - an average of one every 35 metres - before an application was submitted by chain company Coffee#1 to turn a former a shoe shop into an outlet.

Christchurch Borough Council voted to refuse permission for the plans, which would have created eight jobs, following objections from rival cafe owners and local residents, who complained there were too many coffee shops.

Among the establishments already on the High Street are chains like Caffe Nero and Costa, as well as independent businesses the Coffee Pot, Cuckoos coffee bar, Fleur-de-Lis tearooms, Arcado Lounge, Soho, The Boardroom, Wild and Free Coffee, Coast Coffee Co, Kelly's Kitchen, Baggies, Clay Studio and Indulge Yourself.

How do we determine “too many”?

Well, obviously enough, more than people want. So, having moved back an iteration, how do we decide how many people want? Our answer having to be leave it to the market. If 15 coffee shops can all attract enough custom to make a profit then the number of coffee shops that the people want is at least 15. If only 10 can make a profit then the number wanted is, by that measure of where people will spend enough of their own money, 10.

We do not - and cannot - know a priori how many there should be. Simply because the correct number is the interaction of supply and demand, something emergent from observed behaviour. No, we cannot predict with market research and all the rest, New Coke shows us the flaws in that system.

There’s also nothing at all to suggest that the local council is better informed about what the citizenry wants than the citizenry.

And finally of course, not using the council to make the decision means that the current suppliers can’t stick their oar in to limit competition for their own profits.

It’s not which way the decision went here that’s the issue, it’s that the entire decision making structure is incorrect in the first place.

It's the disinformation from some that so annoys about climate change

Anyone watching a little TV these days will see the adverts. The starving polar bear, the heartfelt pleas for money to stop this happening. Then the larger insistence that climate change is threatening the very survival of that species.

Which it might even do but it isn’t as yet:

Too many polar bears are roaming the Canadian Arctic, and the growing population is posing an increasing threat to Inuit communities, according to a controversial new government report which has been bitterly contested by environmental scientists.

The bitterly contested is that climate change is changing hunting grounds thus pushing those bears extant closer to humans. The alternative explanation is simply that there are more bears.

This should be easy enough to work out, count the bears as best we can and see whether there are more of them now than there used to be. The answer being yes.

Thus we should view this insistence on the damage climate change is already doing to polar bears as disinformation.

Do note what we generally say about the larger subject around here - let’s have a carbon tax as that’s the solution to the basic problem. What irks in this instance is the claim which turns out not to have substance.

As with the pictures of polar bears swimming far from land - yes, that’s what polar bears do. Similarly the images of starving such. Yes, that’s how apex predators die. Unlike everything else in the food chain they don’t become lunch as soon as the rheumatics kick in, they die sans teeth sans everything. There are no hospice beds, no Liverpool Pathway, to ease the passing. There’s the inability to hunt then starvation.

It’s the demonstrably untrue claims about climate change that annoy. The propaganda. As they should annoy those who desire greater action - if you base your justifications upon things that can be proven wrong then when they are people are going to more than wonder about the underlying claim you’re making, aren’t they?

At last, an accurate description of Gordon Brown's personal income tax policies

Or rather, an accurate critique of it from the Labour side. Clive Lewis tells us of what we consider the most pernicious of Brown’s personal taxation policies. The manner in which he deliberately drove that income tax system ever deeper into the wallets of the poor. For this is indeed what he did, insisted that people ever lower down the income scale must be paying:

He accused Tony Blair and Gordon Brown’s New Labour of “leaning on those further down the income scale”, while leaving “almost untouched” the “huge fortunes of those at the very top” – citing cuts to corporation tax, and fiscal drag, which brings more people into higher tax bands by leaving thresholds unchanged.

Leave aside that taxation of the rich part and concentrate on that of the poor. This is the part of the system - and Brown made it worse - which we’ve long regarded as actually being immoral. Not just inefficient, or not likely to work well, or constrained by reality, but actively immoral.

For we agree with Adam Smith, that the better off should contribute more than in proportion to their income. Which means to us that the poor not contribute at all as a function of their income. If we have taxes upon apples then people who buy apples, whatever their incomes, should be paying the apple tax. But not income taxes upon low incomes.

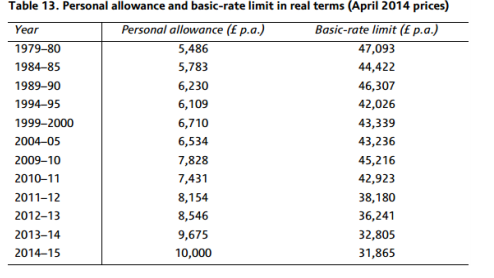

What Brown did was that fiscal drag. Wages tend to rise faster than inflation. So, rises in the personal allowance which are only at the level of inflation drag ever more into that fiscal net - fiscal drag. You can see Brown’s performance on that here. At least once he didn’t raise the personal allowance at all and that at a time of strong wage growth. That’s reaching ever further down into the poor to pay for the British state, not what we think should be done. The effects in real terms - before that background of rising incomes - are here. Incredibly, in those real terms, Brown reduced the value of the personal allowance.

There are many things to criticise over Brown’s tenure as Chancellor. But this is the one we think unforgivable, his deliberate - and obviously complicated and disguised - insistence that the army of Labour voters to be bought by the beneficence of the state be paid for on the backs of the poor. Even if it’s only Clive Lewis who has woken up to this so far that is an advance for the Labour Party, that one understands it. Even if only the one.

A protectionist is someone who argues that you should be poorer so that they can be richer

We’ve made this point before but it’s one that bears repeating. A protectionist is someone who argues that you should be poorer so that they can be richer. Your access to lovely cheap and useful stuff made by foreigners must be restricted so that they can overcharge you for the tat they manufacture.

With that in mind we can now evaluate this suggestion:

Britain must take advantage of Brexit to spur a renaissance in its industrial heartlands by setting tougher standards for renewable energy projects, according to a major Conservative party donor.

Ukraine-born businessman Alexander Temerko has urged Greg Clark, the Business Secretary, to insist that new wind power projects contain at least 60pc British-made components.

Mr Temerko, who was formerly deputy chair of offshore engineering group OGN, warned that the engineering yards of the North East risk losing out to companies in Spain and Germany for lucrative contracts building the parts which will be used to construct giant offshore wind turbines in the early 2020s.

Maybe we do want wind turbines and maybe we don’t want birdchoppers. But if we do we’d like them nice and cheap and made by the most efficient at doing so. If that’s UK onshore producers then good for them, if it ain’t then we don’t want to be buying their tat anyway.

For the call here is that those who own, those who work in, onshore producers should be protected from foreign competition so that they can overcharge us. The argument is indeed that we should be made poorer so they can be richer. At which point the answer is obvious - go boil yer heads.

The Power of Capitalism

Rainer Zitelmann describes his new book, “The Power of Capitalism,” as “a journey through recent history across five continents.” It’s a very timely contribution, considering the bad rap that capitalism receives these days, especially in academe, together with the flirtation with socialism by those who have no experience of what it has brought about in practice.

That is the point. Capitalism in practice has led to wealth creation and prosperity. It has lifted people out of starvation and subsistence, achieving more for humanity in the past few decades than anything in history before it. Zitelman looks at the practice, with chapters on its record in specific places. He looks at Asia, with China’s new prosperity since it allowed capitalism to flourish. He makes the point that it was allowed to develop from the bottom up, not imposed from the top down. He looks at Africa, at South America, and at Europe and the US. Its record is consistent.

He documents, by contrast, the utter failure of socialism wherever it has been tried, explaining why its failure leads its supporters to claim that it never has been tried. Ah yes, it’s that old theory-versus-practice debate. The facts that emerge point in one way: capitalism works, socialism doesn’t. He has a fascinating chapter on “Why Intellectuals Don’t Like Capitalism,” which does more than revisit Hayek’s earlier insights. Zitelmann points out that intellectuals usually deal in ‘explicit’ knowledge, the sort that can be acquired from books and lectures. Many of them fail to realize that ‘implicit’ knowledge, the kind absorbed often unconsciously from surroundings, can be powerful. A child learns the grammar of language implicitly, working out its rules without being taught them. Zitelmann suggests that because entrepreneurs draw largely on implicit knowledge, intellectuals look down on them.

Although many cry for “more state intervention,” Zitelmann documents how this has failed time after time, whereas “more markets,” “more economic freedom,” has worked to create wealth time after time. It’s a fascinating book and a much-needed one.

We've been saying this for some time, we can't afford the welfare state we've already promised ourselves

This is not an observation we’re making for the first time but then the truth does bear repetition. We cannot afford the welfare state that we’ve already promised ourselves. Or more accurately perhaps, we’ve at least so far been unwilling to pay for that welfare that we have been promising ourselves. This is something that Polly Toynbee complains about near endlessly, that we want Scandinavian coddling but we’re unwilling to pay for it through taxation.

We rather differ as to the conclusion from this but then that’s because we understand the proper definition of “want.

”The middle-aged and over 65s may soon be taxed to cover the cost of their later life care if proposals are given the go ahead.

Matt Hancock, the Health and Social Care Secretary, said he was 'attracted to' a crossparty plan for a compulsory premium deducted from the earnings of over 40s and over 65s.

It has been proposed by two Commons committees, the chair of one has said the premium must be compulsory otherwise 'it wouldn't be done'.

We all have desires of course, we even express preferences about them. We’d like free care in our old age for example. But we can only really be said to want them when we’re also willing to pay for them - revealed preferences that is. Which is where our disagreement with Polly comes in. The British are indeed remarkably unwilling to offer a further 10% of GDP, a further 10% of everything, to government in order to gain that social democratic nirvana.

It’s the not being willing to pay that is the important part too, that’s the revealed as opposed to the expressed. That is, we might well say we’d like to have the most embracing welfare state it’s just that when the embrace comes for our wallets, as with new taxation to pay for social care, it turns out we don’t.

Or as we’ve been known to point out, we aren’t willing to pay for the welfare state we’ve already promised ourselves, let alone anything more or new.

It could be that the tax gap is negative

We’ve varied estimates of the “tax gap” out there. Roughly speaking that gap is the difference between what the law says should be collected in taxation and what actually is collected. HMRC thinks about £35 billion, calls from the wilder shores of loondom say £120 billion. The thing is, we can actually construct an argument that the gap is negative, that HMRC collects more than it ought to.

This is, admittedly, difficult with the HMRC figure, although it’s quite obviously too high as an estimate:

Three of Britain’s biggest supermarket groups have won a legal victory worth up to £500m, following a court battle over business rates on cash machines installed at their shops.

The court of appeal ruled on Friday that cash machines located both inside and outside stores should not be liable for additional business rates, which are a form of property tax on businesses collected by the government.

Several retailers including Tesco, Sainsbury’s and the Co-op had fought in the courts against the tax rules set by the Valuation Office Agency – the arm of HM Revenue and Customs responsible for setting business rates – which had claimed that ATMs should be additionally assessed.

The court verdict means the supermarket chains are in line for a multimillion pound windfall from tax refunds, which the property advisory company Colliers estimates is worth about £500m.

The case dates back to a 2013 decision by the government to charge rates on “hole-in-the-wall” cash machines, which was backdated to 2010.

That is not the negative of tax avoidance, that’s the negative of tax evasion. HMRC has been collecting tax which is not legal to collect - that is the opposite of not paying tax which is legally due, tax evasion. Sadly, our system is asymmetrical, no one will be threatened with jail over this.

Still, including what HMRC does collect but shouldn’t - not something included in anyones’ estimates - will close that tax gap, won’t it?

Once we look at those wilder claims, that £120 billion say, then it’s trivial to show that the gap is negative. For the larger sum includes what the calculator thinks should be taxed but which the law doesn’t. We differ with those calculations, insisting that large number of things which the law says should be taxed should not be. Thus the gap is negative, HMRC collects more revenue than we think just or righteous.

Yes, yes, what fun etc. But it is still true that we have the opposite of tax evasion, the collection of taxes which are not legally due, something that really should be in the figures.

What a delightful complaint about Amazon's new headquarters

An instructive little complaint about where Amazon has decided to put its new HQ building. Or, as it happens, buildings:

This engineered airdrop of tech people threatens to destroy America’s delicate distribution of unwanted wealthy demographic groups. Silicon Valley and Seattle get to deal with the techies. Los Angeles gets the Hollywood people. Washington gets the politics nerds, and New York gets finance types. We have each adapted to our own particular crosses to bear.

The complaint is against people earning good livings, in good jobs. It’s actually against the very process of wealth creation itself. Something which perhaps rather militates against that more general idea of good livings, good jobs, wealth creation for all.

That, to our mind at least, being the point of our having one of these economy things in the first place. The idea that through voluntary cooperation we can and will make the lived experience of each and every human being better. This being something that requires the generation of economic wealth so that economic wealth can be consumed.

There’s also only us people here, that then meaning that it has to be us people generating that wealth that can be consumed. At root, this is simply what an economy is. But here the complaint is that while we’d all just love to be doing the consuming we don’t want any of those producers around us.

It’s as alarming - or confused if you prefer - an idea as that traditional British disdain for those in trade. But then there’s nothing quite so conservative as a modern day lefty, is there? Yea, even progressives from Queens.