Apparently the people who run universities are entire, complete and total idiots

It’s a rather startling claim and one that given our general view of those who can’t and therefore teach one we might even believe - that all those who run Britain’s universities are idiots. We don’t quite believe it though as we’ve met some goodly portion of them.

Yet this is what is being claimed here:

Tory education reforms are giving private school pupils a huge additional advantage in the hunt for university places and jobs by allowing them to sit easier GCSEs than the more rigorous exams that are being forced upon state schools, new official figures suggest.

Data released in parliamentary answers, and research into the exams chosen by private schools, shows the extent to which the independent sector is still opting for less demanding, internationally-recognised GCSEs (IGCSEs), which state schools are progressively being barred from using.

Let’s entirely accept the underlying contentions here. That IGCSEs are easier than GCSEs, the private sector sticks with the IGCSEs and that this means that the private sector pupils are getting better exam results when we look purely at grades.

Does this give those private sector pupils an advantage when applying to university? Well, only if those running the universities are entire fools.

People applying to Britain’s gilded cloisters come from all sorts of educational backgrounds. There will be those who have come up through the British school system, those from various remnants of the colonial schooling system, baccalaureates, perhaps the international bac, we’re sure that here will be graduates of Finland’s famously egalitarian system, of Sweden’s variation, or Russia’s and so on. Even some who managed to scrape through American high school.

That is, those who select pupils for entry into the universities are already well versed in the intricacies of different sets of qualifications. Thus entirely capable of distinguishing between 15 A*s at IGCSE and 5 Cs at GCSE. Actually, if they can’t, then what are they doing there?

To believe what is being claimed is that the universities are being run by those entirely unqualified to do so. Which, if true, suggests we’ve a bit of clearing out to do rather than worrying about who takes IGCSEs no?

Optimists

There is a tendency among those of the neoliberal persuasion towards optimism, the confidence that humankind can solve its problems and emerge into a better world, one full of opportunities, choices and chances, and one that will enable more people to live more fulfilled lives. An early exponent of this attitude was Julian Simon, author of "The Ultimate Resource," which was human ingenuity and creativity. Modern representatives of this approach include Matt Ridley, who wrote "The Rational Optimist," and Johan Norberg, author of "Progress: Ten Reasons to Look Forward to the Future." Both authors share Simon's confidence that humans will meet and surmount the challenges they will encounter. Both see the world as far, far better than it was, and both look to an even better future.

The question arises as to which comes first: is it confidence in the power of markets and the spontaneous interaction of millions that draws some to be optimistic about the future? Or is it that temperamental optimism leads people to endorse markets and neoliberalism? There might be another factor, too, in that optimists tend to see the world as it is, using more reason and analysis to evaluate it, rather than an emotional response to how far it falls short of the way it might be imagined. To optimists the evidence is overwhelming that the world is better than it was in terms of offering people better lives. It is also obvious to them that people can, by care, effort and application, make it better still.

British public sector pay isn't low, sorry, it just isn't

Those who work in the National Health Service are being warned against leaving the public sector pension scheme. This sounds like extremely good advice as on the numbers given this is the finest investment in the world. Perhaps the occasional equity will do better but this one comes with a government guarantee:

NHS workers are abandoning their generous gold-plated pensions in droves, despite warnings they could face poverty in retirement.

Concerns have been raised over an "epidemic" of workers opting out of the NHS pension scheme after nearly 250,000 staff withdrew from the scheme in the past three years.

Workers who opt out could be giving up pensions worth around nine times what they save, Royal London hospital warned last night.

It said figures revealed under the Freedom of Information act found that 245,561 workers across the NHS in England had opted out of the NHS pension scheme in the past three years.

A nurse earning £25,000 annually who opted out for a year could save £1,420 by doing so.

But it would cost a lump sum of around £13,000 - around nine times the £1,420 saving - to fill the pension hole caused by that one year of lost pension in retirement, Royal London said.

When people opt out they also give up large employer contributions into their pension pot.

There are claims that the British public sector - most especially those Angels of the NHS, the nurses - is underpaid in some manner. But we’ve got to understand that pensions are simply deferred pay. The pension that accumulates this year of your labour is payment for this year of your labour as assuredly as anything that turns up in the wage slips for this year.

Further, given the vagaries of final, average, defined contribution and so on pensions schemes the only useful valuation is the net present value of that future income stream.

When we do this across all of the public sector we get to an interesting result. Largely, and in general, in terms of wages the public sector pays better - adjusting for experience, training, education, all those things - for low end roles than the private and less well for top end jobs. But that’s for wages only. Add in pensions, a useful rule of thumb here being those public sector ones are worth an additional 30% of salary, and the pay scales tip to the public sector doing rather better than the private.

Not that we think so ourselves but it’s possible to argue that this should be so too, those who work for us should be well remunerated perhaps. But what this does show is that the argument that the public sector should get pay rises to keep up with the private workforce is simply false.

Now, what was it Hayek said about the difficulty of planning economies?

This was it, wasn’t it? In his Nobel Lecture, The Pretence of Knowledge, Hayek pointed out that we can’t plan economies because we can’t know what is happening in them. Without the information of what is going on we can’t - logically enough - determine what should happen, nor how to make it happen.

We admit to a tad of simplification there but that’s rather what he did say. Fortunately we currently have a government intent on proving this contention to us, which is nice, reality proving theory:

The Government has been accused of “sheer hypocrisy” for urging schools to become plastic free zones, after it emerged that its own fruit and vegetable initiative uses plastic packaging.

Under the scheme, all children at aged between four and six-years-old who attend state-funded primary schools are given a daily portion of fruit or vegetables. These are delivered to schools by Foodbuy, a Government supplier, wrapped in single-use plastic.

This week the Education Secretary, Damian Hinds, called on headteachers to contact their suppliers and ask for all deliveries to be made with packaging that is reusable or recyclable.

He said schools should stop using items such as plastic straws, bottles, food packaging and plastic bags and opt instead for sustainable alternatives.

It’s not that the Minister can’t try to control it’s that he doesn’t even know. Doesn’t know not just what we 65 million out here are doing, or the generality of the government, but doesn’t know what his own department is doing on a daily basis.

At which point this cloud of ignorance is going to make planning everything a bit difficult, as Hayek told us.

Of course, given that this about plastics is all a religious mania rather than anything rational there’s this as well:

Ms Sutherland said that using plastic packaging for fruit and vegetables is “one of the most indefensible uses of plastic”, since there are so many more environmentally friendly alternatives.

But if there are so many options which are better then why is it that people are using the one that isn’t better? We do tend to think that people aren’t stupid, that they optimise their use of resources. Rather a lot of our observation of the world confirms this insight. So, to claim that some other manner is better does require answering that question, if it is better then why aren’t people already using it?

Sure, it’s possible that there is a good reason why not. But we do need to know what it is.

Virtue signalling countries

It is common in developed countries for some people to signal their virtue by ostentatious behaviour changes. Although their changes often make zero difference to whatever causes they espouse, it does enable them to feel they are “doing something,” and to show their fellow citizens that they are on the side of the angels. Whole countries are not immune to such displays of virtue. Germany, for example, is phasing out nuclear power. It has closed 8 of its 17 reactors, and committed itself to closing the remainder by 2022. This is done “in the interests of the environment,” even though nuclear power pollutes far less than the fossil fuels it substitutes for.

The UK has joined the virtue signallers by proposing to double its 5p plastic bag charge, and to push schools to eliminate use of plastic. The UK’s contribution to plastic in the oceans is tiny. Ten rivers worldwide carry 90 percent of plastic entering the oceans, according to a paper from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig. Two of them, the Nile and the Niger, are in Africa, and the rest are in Asia: the Indus, Ganges, Amur, Mekong, Pearl, Hai he, Yellow and Yangtze rivers.

The Yangtze River in China is identified as the worst offender, putting up to 1.5 million tonnes of plastic into the sea every year. The Thames, by comparison, is responsible for only 18 tonnes of plastic into the ocean. Of course it is a good thing to play our part to reduce this, but the difference it will make to the world’s total is negligible. We might be better employed offering prizes to any researchers who can devise ways of dealing with the plastic others are dumping, perhaps by engineering micro-organisms that can digest it.

Unless and until we contribute to ways of actually solving the problem, we are simply virtue signalling and giving our ministers a chance to “look green” without actually making any difference.

But why this insistence upon recycling plastics?

As we’ve pointed out more than once around here we really don’t want to kill off sea life with the waste products of our civilisation. This includes plastics floating around the oceans. But this means managing the wastes from our civilisation, not either recycling them all or not having wastes or a civilisation at all.

With plastic we could recycle, of course we could, at some cost. We could also not use plastics, again at some cost. We could also burn them once used but there are at least some who say this should not happen either:

The answer to plastic pollution is to not create waste in the first place

Well, no, not really. Taking a scarce resource and transforming it into something of use to humans is rather the definition of having a civilisation at all. So, it’s management of the waste which matters:

On the bright side, the ban sparked a much needed conversation about improving domestic recycling infrastructure and recycling markets, and has forced both companies and the public to re-evaluate the products and packaging that were previously assumed to be recyclable. But the ban has also been used as a wrongful justification for burning trash in incinerators.

Waste incinerators became popular in the US in the late 80s, until harmful emissions of mercury and dioxins, toxic ash, technical failures, and prohibitive costs soured the public on the industry. However, there are still more than 70 relics left over from that failed experiment which continue to pollute surrounding communities and drain city coffers.

Well, we’re not sure we believe that about incinerators but a little technical knowledge is useful here. We are, after all, 40 to 50 years advanced from when those incinerators went up and it is true that we’ve learned more about PCBs and dioxins over that time. Modern incinerators function at higher and more stable temperatures meaning that those harmful chemicals aren’t created at all, let alone released.

But OK, let’s roll with the assertion for the moment anyway. That still doesn’t mean that recycling or non-use are our only options. There’s still the burying it in landfill option to consider. We’ve no shortage of holes in the ground, plastics don’t pose a problem as they rot as they largely don’t. So, what are the costs and benefits here?

Don’t use plastics, do but recycle them, do and bury them once used. Which of these makes us richer - that being what we want to know, which has the greatest benefits as against the least costs?

After all, the idea that we dig up hydrocarbons, use them, then bury the hydrocarbons again isn’t exactly a grand rape of Gaia now, is it?

Osmotic desalination just took a big step

When I wrote "Britain and the World in 2050" I forecast that despite UN talk of water shortages and some alarmist predictions of "Water Wars" by mid-century, the most likely outcome would be that access to very cheap energy would enable osmotic desalination to solve the problem.

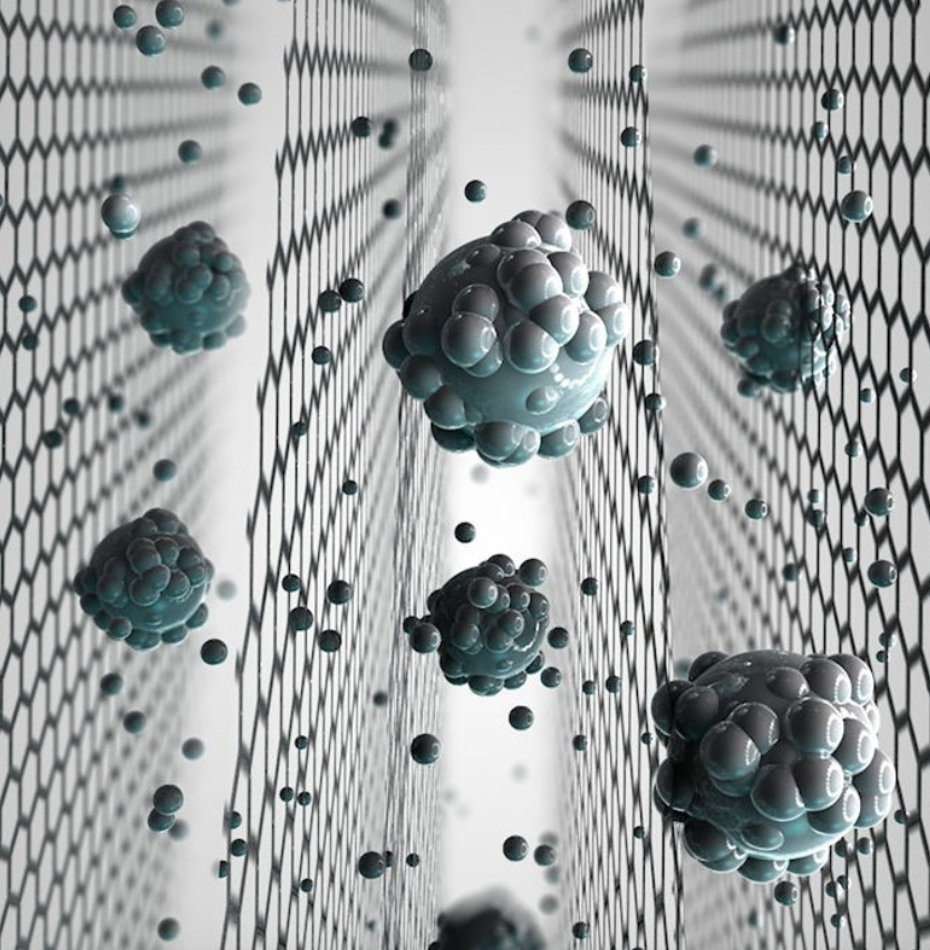

The problem with current membranes used to turn seawater into drinkable quality water is that it is very energy intensive and requires high maintenance to clean the salt sludge from the membranes. The first of these will be solved by the abundance of low cost gas from fracking, and a continuing steep decline in the cost of photovoltaic energy.

Now a major breakthrough in membrane technology has been announced. Graphene-oxide membranes have had the problem that because they swell slightly in water, smaller salts flow through them with the water, even though they block the larger molecules. A University of Manchester group has just revealed in the journal Nature Nanotechnology that it has developed a way to avoid the membrane becoming swollen in water, and to precisely control the its pore size. This enables the unwanted salts to be sieved out at speed, leaving clean, drinkable water.

The drive now is to scale up the technology so it is capable of large-scale, cost-effective production. In addition it is hoped that smaller-scale versions can be developed for countries lacking the finance to fund large-scale plants. As with so many anticipated problems, human creativity and resourcefulness seem capable of stepping up to the plate with technological solutions to them.

Why are they wasting this money upon the High Street?

The High Street is changing use, that much is obvious. The rise of the internet, of online shopping, means that we’ve a certain surplus of retail space in the country. It’s not a coincidence that, as we’ve pointed out before, some 15% or so of consumer spending is now online, some 15% of retail space in the country is empty.

Such change is rarely pretty nor enjoyable close up but change is indeed a defining feature of a well functioning economy. For we do, as technology changes and enriches us, change our behaviour to partake of those new riches. That doesn’t justify spending our wealth upon the doomed, as is being suggested here:

Britain’s high streets will receive a £675 million cash injection under Government plans to turn empty shops into tea rooms, community centres and new homes.

As of today, local authorities will be able to apply for grants from the Future High Streets Fund, with £55 million set aside for the restoration of historic buildings at risk of falling into disrepair.

The fund is the latest in a series of policy announcements announced by ministers recent months to reverse the decline of the country’s high streets, which have been decimated by the rise of online retailers and ecommerce.

With thousands of retail units falling vacant this year, calls for Government intervention have grown as major retailers including Debenhams and House of Fraser announced plans to shut dozen of stores due to dwindling profits and footfall.

This is the Planner’s Fallacy written out for us again. Those who would design our lives and urban spaces didn’t see that online shopping coming. They were entirely blind to the possibility and the effects. We just went ahead and did it through our voluntary interactions. They’re equally blind and ignorant as to what what we’d like to use those urban centres for in the future. The reason being that we’ve not a scoobie either and we’ll be the people doing the using through our voluntary interactions.

For what should be done with town centres? Dunno. We dunno, you dunno and the planners are in an entirely dunno clueless state. So, how can any planning be done? Money allocation to what we don’t know what to do about is wasted, entirely so.

There is a system we can use, of course there is - the market. Free up all the rules and regulations about what may be done. Change of use, all that sort of stuff, planning regs, requirements to show public benefit and so on. Just allow our own voluntary interactions again to work through the problem. As Hayek pointed out, it’s the only system we’ve got that actually works.

For the Great Truth is that what happens to High Streets and urban centres is emergent from what we decide we’’d like to do with them in the absence of quite so many shops. So, better let us get on with it so we can find out what we would like to use them for.

And, err, stop spending money we don’t have on what we dunno about.

The upcoming space industry

The mid-December flight of Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo has sparked interest in the commercial exploitation of space. The craft was Burt Rutan’s rocket plane, following on from his winning of the X-Prize in October 2004 with his SpaceShipOne, funded by Paul Allen. It was then that Sir Richard Branson stepped in to fund its successor, promising space tourism “within a couple of years.” Important though the recent flight was, it reached only 82km, which Branson has redefined as “space.” The accepted international boundary is the Karman Line at 100km, which Rutan had to reach twice to win the X-Prize.

The phrase “a couple of years” resonates because it reveals the difficulties of achieving safe sub-orbital flight for paying passengers. I was the first person in Britain to sign up and pay a deposit for such a flight late last century. I was told then that it would probably be in “a couple of years.” Since then it has always been two years away. However, the recent flight indicates that we might be nearing the elusive goal. Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin and Elon Musk’s SpaceX are in competition with Virgin Galactic to carry the first fare-paying passengers into space. Both of the competitors have achieved many uncrewed flights into space.

After years of lacklustre interest in space, the UK has finally moved to enter what is expected to be a multi-billion pound industry by designating several areas as spaceports. Vertically launched rockets and satellites will initially lift off from the A ‘Mhoine peninsula in Sutherland, at a site between Tongue and Durness, and a £2m development fund will go towards spaceports for horizontal launches from Prestwick, Newquay, Campbeltown and Llanbedr.

What is needed now is for government to speed up the regulatory environment under which these launches will take place, and to refrain from a heavy-handed approach that might use the precautionary principle to hold back development. The aim should be to give the UK an important niche in a fast developing industry.

Piketty's World Inequality Report is less than it might seem

Whether inequality is increasing or not very much depends upon what it is that we’re trying to measure. Inequalities of lifestyle? Consumption? Income or wealth?

How these are measured also matter rather a lot. And it would appear that the latest attempt, the World Inequality Report and associated work from Thomas Piketty et al is rather less accurate than many seem to assume.

We defer to James Galbraith on this subject - someone we’ve discussed the larger issue with at times. It’s entirely true that our world views don’t entirely coincide but we do agree that facts is facts and that’s where we’ve got to start from. For if we don’t accurately analyse whether there’s a problem at all, nor the causes of it, then we’re just never going to find a solution.

Galbraith’s new paper:

A more interesting claim lies in the focus on national institutions and policies, which is justified by the comment about ‘different speeds’. Differences in the behaviour of inequality over time are indeed evidence that national institutions matter. But if it should appear instead that movements of inequality are correlated across countries, that inequalities move in the same way in neighbouring countries or even across continental distances — that would lead toward a very different view. Namely, it would suggest that global forces tend to drive the movement of inequalities across countries, even if they do not work everywhere with the same force or at the same rate. We shall return to this issue, as work with different data strongly indicates that powerful global macroeconomic currents affect the movement of inequalities, especially in smaller countries and the developing world.

Quite so, international happenings are likely to have international causes. Our own insistence would be - note ours, not Professor Galbraith’s - that integrating billions of excruciatingly poor labour into the global economy would, we would predict, increase inequality by increasing the pressures on low skill labour everywhere. The benefit of this cost being that those excruciatingly poor become less so as economic growth happens. As has been happening these past few decades.

We’d also insist that this is a benefit that is worth the cost of greater inequality.

It’s also, eventually, self-solving as catch up growth reduces that competitive pressure. But the important point to take from this being that if it’s not domestic political decisions causing the rise in inequality then it’s most unlikely to be domestic political action which will reduce it.

The lesson of this paper though is that the evidence base being used to make the wilder claims of inequality growth is, well, that evidence isn’t very good.