“Father of the Constitution”

James Madison was born in Virginia on March 16, 1751. He was to play a pivotal role in developing the Constitution of the United States, which replaced the Articles of Confederation that were ratified after the War of Independence. Madison thought the Articles, in leaving most power to the state legislatures, had left the national government too weak to raise funds or to maintain an adequate national army.

Madison wanted a federal government established, with checks and balances that divided power between the legislative, executive and judicial branches. His “Virginia Plan” formed the basis of the Constitution. In the run-up to its ratification, he co-authored a collection of 85 articles and essays with his colleagues Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. These were dubbed “The Federalist Papers,” and sought to win the argument for a federal government.

Madison’s early drafts of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights earned him the nickname, “Father of the Constitution,” though he modestly stressed the role played by others. The Bill of Rights, a group of 10 amendments to the Constitution, gave written guarantees for such issues as freedom of speech and religion, the right to bear arms, and the right not to be forced to testify against oneself. These guarantees, written by Madison in response to the misgivings that some held about the proposed Constitution, succeeded in having it ratified.

The United States thus became a country with a written Constitution, one governed by laws rather than by men. The rights that it enshrined are no less relevant now than they were then, and have lasted through the 230 years that have elapsed since. The model set out by that Constitution is that the people can be protected if power is dispersed, and if lawmakers themselves come under the law.

Madison himself was honoured as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, and was elected as its fourth president, serving from 1809 to 1817. He left a name that shines bright in the annals of liberty.

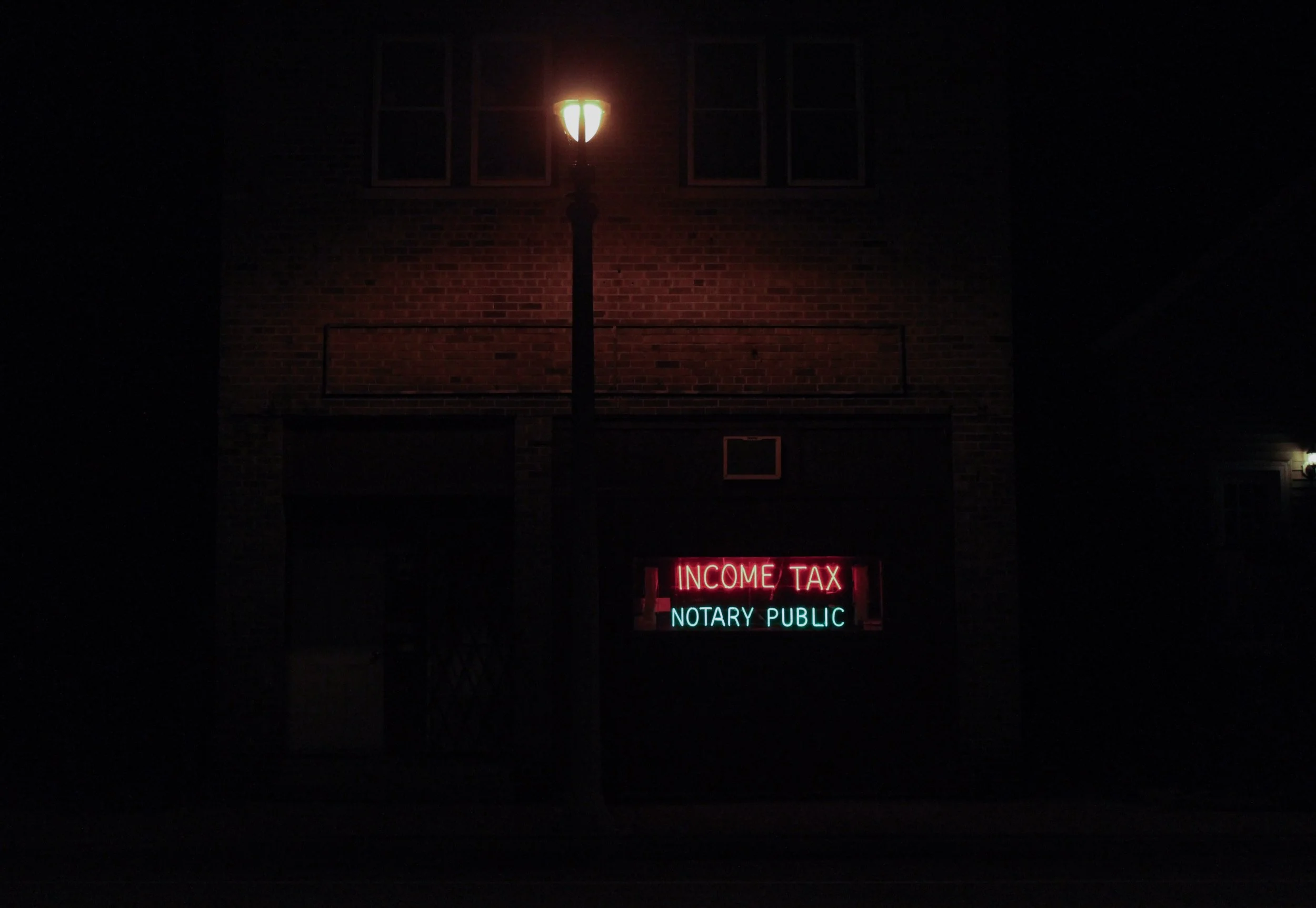

Well, yes, this is how it works, taxation makes people poorer

It is entirely true that some of the things government does makes us, all or some people, richer. Equally true is that the act of taxation itself makes those being taxed poorer. So this is not exactly a great surprise:

Stealth taxes are forcing more people into higher tax brackets and cutting child benefit payments because the thresholds are not moving in line with inflation or wages, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has warned.

As the ageing population puts more strain on the health and pensions budgets, its likely the Government will have to impose significant further tax rises on high and middle earners in the years ahead.

Relying on inflation to pull more people into higher tax brackets means families are paying more tax even though their incomes have not risen in real terms, leaving them worse off overall.

Increase the taxation of the population and the population will be, as a result, poorer. Yes, again, it’s worth considering what the cash is then spent upon but this is the effect of the taxing itself - people have less money themselves, they are poorer.

The actual mechanism is called fiscal drag. Don’t upgrade taxation brackets by earnings growth say. Earnings do grow, generally speaking, in real terms over time. So holding the brackets static captures ever more people at ever lower percentages of average income. A more extreme form is not even to upgrade by inflation - Gordon Brown did that with the personal allowance at least once.

Our own - successful - campaign around here to raise the personal allowance to £12,500 was at heart just a reversal of decades of this fiscal drag. There was a time when only those on greater than median earnings entered the income tax net. Now it starts before even a full year of work on the minimum wage. And that’s after the near tripling of that personal allowance - that’s the effect of fiscal drag over time.

The IFS’s basic contention here, tax people more and they’re poorer, is uncontestable. Which does open up that question of why we keep trying to d so. It’s not a known aim of economic policy to make people poorer now, is it?

Clothes rationing ended long after the war

Clothes rationing ended on 15 March 1949. In World War II Britain, clothes rationing had been introduced in June 1941. Clothing materials were needed to produce the uniforms that were by then worn by a quarter of the population.

Most things were rationed in the drive to be more self-sufficient in the fight against Nazism. Petrol came first, then food was severely rationed. Everyone had to register at chosen shops, and was given a ration book with coupons. Shopkeepers were given enough food for registered customers. Would-be buyers took ration books with them when shopping, so that coupons could be torn out or cancelled.

In 1939 it was petrol. Then in 1940 bacon, butter and sugar were rationed. Then came rationing for meat, tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, eggs, lard, milk, and canned and dried fruit.

When clothing was rationed, it was calculated to provide one change of outfit per year, with more coupons for growing teenagers. The ration was based on how much labour went into a garment, and how much material was used. A dress could take 11 coupons, whereas a pair of stockings took only 2. Men’s shoes took 7 coupons, while women’s shoes were only 5. In 1945 an overcoat needed 18 coupons; a man's suit, 26–29, depending on the lining.

No coupons were needed for second-hand clothing, but prices were fixed. The ‘Make do and Mend’ campaign, supported by poster advertising, urged people to repair rather than replace their clothing, thereby engendering a generation of skilled repairers.

In 1942 clothing austerity measures were introduced to limit the number of buttons, pockets, pleats, and decorations on clothes, and shoes and boots became hard-to-get items. The ‘Utility’ brand denoted basic, government approved clothing. As a child, I wore a ‘Utility’ raincoat.

Rationing led to black markets. ‘Spivs’ offered additional non-rationed supplies to those who could afford it. This was a lucrative industry, and the maximum five-year jail sentence for being a ‘spiv’ was not much of a deterrent.

After the end of the Second World War, rationing continued. In some cases it became stricter after the war. With many men still in the armed forces, an austere economic climate, and a centrally-planned economy under the post-war Labour government, resources were not available to increase production and imports. Strikes often made things worse. Cheating became widespread, and often the ration books of the dead were kept and used by their relatives

In 1950 the Conservative Party played upon public resentment at continued rationing, scarcity, controls, austerity and government bureaucracy. People had seen how the socialist policies of the Labour Party had failed to alleviate shortages and were ready for alternatives. The Conservatives, under Churchill, staged a political comeback with the slogan “Set the people free,” and won power in the 1951 general election. Their appeal was especially effective to housewives, who found shopping conditions harder after the war than they had been during it.

It was alleged that clothing rationing ended because attempts to enforce it were thwarted by massive illegality, including black markets, unofficial trade in clothing coupons, many forged, and bulk thefts of unissued clothes ration books. Either way, its ending in 1949 came too late to save the Labour government. People were fed up of shortages and rationing, and turned to the Conservatives to end them.

A small test of how the state expands - that period poverty charity

Now that the mistake has been made to hand out sanitary products for free in schools we can use this as a little test of one of Milton Friedman’s contentions. That there’s nothing so permanent as a temporary government program.

For Phil Hammond has, along with that freebie stuff, announced that tampons etc will be VAT free the moment we are free of Brussels and thus able to make them so. OK, we’re fine with that, both that they should be VAT free and also that domestic taxation should be something decided domestically by the domestic legislature.

It’s just that the VAT collected has been, for some years now, sent into a special fund to pay for special projects:

The government has already pledged to remove VAT on sanitary products – the so-called “tampon tax” – when the UK leaves the European Union. Currently it channels the revenue it raises to good causes.

Now that the problem has been entirely solved - both the VAT and the schools poverty thing - how many of those good causes are going to be defunded? And how many will end up being absorbed into some other funding stream?

It’s a good test of that contention, isn’t it? The state lingers on, as bureaucracies tend to, even when we’ve entirely solved the issue by other means. We are going to be able, here, to test that contention in detail.

Karl Marx – failures and successes

Karl Marx died 134 years ago, on March 14th, 1883. His work was hugely influential, though not in the way he conceived. He interpreted history in terms of class struggle, believing that societies develop though conflict between those he called the bourgeoisie, who controlled the means of production, and the proletariat, who provided the labour that made the products.

Marx followed the labour theory of value, as had Adam Smith, holding that the value of goods lay in the labour it cost to produce them. The various inputs of production could be valued at the labour it had taken to make them. From this came his view of profit as “surplus value” that derived from exploitation, not paying the worker the true value of his product. The problem with this is that value is not a property that resides in object. It exists in the mind because people value things, and value them differently. We value things; they don’t have value. If nobody values an object, then it has no value, no matter how much labour it might have taken to produce it.

Marx also followed a Hegelian view of how change takes place. In Hegel’s view a state of affairs (the thesis), generates contradictions within it (the antithesis), and from a violent clash between the two, a new order emerges (the synthesis). This, in turn, becomes a new thesis, and the cycle is repeated. History, on this model, moves in triads, though a series of violent clashes. Marx thought that capitalism would and did generate internal contradictions, such as the class-consciousness that comes from putting workers together in factories. From these would come the violent clashes that would ultimately see capitalism replaced by socialism. Revolutionary violence was the force driving change.

It is a pity that Marx had not given more attention to the Darwinian view of change. His “Das Kapital” was published in 1867, eight years after Darwin’s “The Origin of Species.” Marx had read Darwin, and admired the way he accounted for human origins without recourse to religion. What he didn’t spot was the mechanism of change, by which innovations gradually over time spread to become the new norms. It provides a more fruitful and convincing account of how human societies develop and change, by evolution rather than revolution.

On the Marxist analysis, the climactic struggle and outcome should have come first in the most advanced and developed economies, those in the fullest and final stage of capitalism. It did not, of course, because Russia was not among them. Lenin simply did what was needed to win power, and rewrote the book afterwards. Mao later did the same in China. Neither case followed the Marxist model of historical progression.

Where Marx did succeed was in pointing to the way in which changes in the economy, specifically in the means of production, lead to changes in its social organization and, indeed, to a society’s culture and its laws. In his 1847 “Poverty of Philosophy,” he wrote, “The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist.” Marxists tend to over-egg this insight if they claim this to be the sole cause behind social change, but other historians regard it as one useful key, among others on the chain, as they seek to unlock and understand why the past happened as it did.

The twin tub washing machine at £1,960 a piece

It’s interesting what can be learnt from the obituaries page. A man, John Bloom, made - before he lost it again - a fortune from selling twin tub washing machines to the masses. A proper fortune, Mayfair, Rolls Royce and all.

He had a flat in Mayfair in the heart of London, a 150ft motor yacht that had a lift linking the bridge to the master bedroom, and a Rolls-Royce Phantom in which, for a publicity stunt, he gave the Beatles a ride down Fleet Street.

Such inequality, such capitalist exploitation of the toiling masses.

Except, well:He had done it by shaking the “white goods” industry to its very foundations in what had become known in the press as the “washing machine wars”. His approach was simple yet revolutionary. His company, Rolls Razor, cut out the middle men, the retailer and the wholesaler, by selling 6,000 washing machines a week directly to customers at a drastically reduced rate of almost half-price.

...

In 1958 he advertised the Electromatic twin-tub washer-spin dryer at 39 guineas (£980 today), undercutting the high street retailers by 50 per cent.

Who got the better end of the deal there? In aggregate? The 6,000 households a week saving near £1,000 each or the bloke with the fancy lifestyle? Clearly, it’s that £6 million a week being saved, isn’t it, for no one at all is thinking that Bloom was off with £6 million a week himself.

As it always is with this entrepreneurial capitalism of course. Most assuredly those who succeed gain that luxury. But it only happens if they’re making their customers vastly better off by their actions. For, of course, the consumers won’t be lining up to buy the stuff unless it does make them better off.

And doesn’t the thought of the £2,000 washing machine set just sting these days?

When the barbarous relic hit $1,000

On March 13th, 2008, gold prices on the New York Mercantile Exchange passed $1000 per ounce for the first time in history. One reason gold is so valuable is that there is not much of it about. The world annual gold production would make a cube of just 14 feet on each side. All of the gold ever produced by anyone throughout history would only reach one third of the way up the Washington Monument.

Another reason for its value is its comparative incorruptibility, which is one reason behind its almost universal acceptance. France’s President de Gaulle, who favoured a return to currencies fixed to the price of gold, in a 1965 press conference sang its praises: “That which is immutable, eternal.” He resented the influence that the dollar gave to the US, and he wanted a return to the gold standard, which would not be the political instrument of any one country.

A more surprising “gold bug” was ex-Federal Reserve Chairman, Alan Greenspan. In 1966 he wrote "Deficit spending is simply a scheme for the confiscation of wealth. Gold stands in the way of this insidious process.” He later admitted he was in a tiny minority at the Fed who favoured a return to the Gold Standard.

In modern times the lessons of Zimbabwe and Venezuela point to the catastrophic effects that can follow when a corrupt or incompetent government finances its lavish spending by printing more of its currency.

The Gold Standard favours the countries that have gold deposits, but it has the advantage of making it difficult for governments to inflate prices by expanding the money supply. It engenders long-term price stability because the money supply can only grow at the rate at which gold is produced. Inflation can come, though, if a major new source of gold is developed, as happened with Spanish gold from the New World, or with various “gold rushes.”

On the other hand, a fiat currency, one backed by the government that issues it, can be increased in supply at the rate of growth in the economy. Some economists think that limits to the supply of gold act to limit the economy’s ability to supply the capital needed for growth. John Maynard Keynes said in 1924, “In truth, the gold standard is already a barbarous relic.”

Furthermore, some point out that a fiat currency gives a country the ability to handle economic shocks. The fact that governments could control the money supply in the wake of the 2008-09 financial crisis is said to have helped prevent even worse effects from following.

The rise of gold through the $1000 per ounce barrier happened some years after Chancellor Gordon Brown sold about half of the UK’s reserves of it. Between 1999 and 2002 he unloaded about 395 tons of it at an average of about $275 per ounce. By announcing his intention in advance, he virtually ensured rock bottom prices. It subsequently rose to over four times that level, but the currencies he traded it for have not done as well.

FAA's instructions to Boeing either meaningless or dangerous

If a bureaucracy exists then that bureaucracy must be seen to be doing something. Whether what the bureaucracy does is useful isn’t the point, there are budgets and reputations to protect. Which brings us to this instruction from the FAA to Boeing:

The United States will mandate that Boeing Co implement design changes by April that have been in the works for months for the 737 MAX 8 fleet after a fatal crash in October but said the plane was airworthy and did not need to be grounded after a second crash on Sunday.

An Ethiopian Airlines 737 MAX 8 bound for Nairobi crashed minutes after take-off on Sunday, killing all 157 aboard and raising questions about the safety of the new variant of the industry workhorse, one of which also crashed in Indonesia in October, killing 189 people.

Boeing confirmed the Federal Aviation Administration's announcement late Monday that it will deploy a software upgrade across the 737 MAX 8 fleet "in the coming weeks" as pressure mounted. Two US senators called the fleet's immediate grounding and a rising number of airlines said they would voluntarily ground their fleets.

The company confirmed it had for several months "been developing a flight control software enhancement for the 737 MAX, designed to make an already safe aircraft even safer."

Clearly we’d prefer that planes don’t fall out of the sky and so such an upgrade is a useful idea. However, do note that flight control software is some of the most complex we create as a civilisation. Not so much that the task itself is particularly heinous, it’s that the error rate has to be extremely low. How Google load balances affects the speed at which pages appear on your screen. How flight control software works determines whether, well, whether planes fall out of the sky. We’ve rather different reliability desires between the two.

So, Boeing has been working on this upgrade for months and presumably they’d be rolling it out when it’s ready. That’s why they’ve been working on it for months. The FAA now says that it will be rolled out and it will be by a certain date.

There are two and only two possibilities here, given that Boeing has indeed been working on this for months. The FAA is just instructing Boeing to do what Boeing was going to do anyway. In which case it’s meaningless other than to protect the FAA’s reputation and budget. Or the FAA is insisting that this gets rolled out before Boeing would have done so, before Boeing thought it might be ready. In which case the bureaucracy is creating danger.

Bureaucracy, useless or dangerous? Both is difficult to allege and neither isn’t really possible.

Overpopulation and scarce resources

Harry Harrison was born on March 12th, 1925. When I met him in 1984, he was dividing his time between the Republic of Ireland, where he enjoyed tax free status as a creative writer, and his flat in Brighton. He grew up as an American, but lived in many countries and eventually took Irish citizenship.

He was a prolific writer of science fiction, producing the “Deathworld” series and stories featuring “The Stainless Steel Rat.” His 1966 novel “Make Room, Make Room” brought him to popular attention when it was adapted into the 1973 movie, “Soylent Green,” starring Charlton Heston and Edward G Robinson. It is set in a grim and grimy New York, vastly overcrowded as the world’s population has exploded, leading to a shortage of resources and food. People are fed on bland vitamin blocks produced by the all-powerful Soylent Corporation, and made of soybeans and plankton. The exception is the new Soylent Green, which we discover at the end of the movie is made of recycled people.

It didn’t happen. He set his story in 1999, and although the world’s population did reach 7 billion, as he predicted, it did so 12 years later. This was not the disaster he foretold, and the world did not run out of resources or food, or become so impossibly overcrowded that people had to sleep on the stairs of apartment buildings. Nor did services collapse.

Just as Harry was writing his doom-laden story, the Green Revolution was getting under way. Norman Borlaug was pioneering new technologies, including high-yielding varieties of cereals, especially dwarf wheat and rice, plus chemical fertilizers and irrigation, all combined with new farm management techniques that hugely boosted farm productivity and food production. We didn’t run out of food.

Julian Simon won his famous bet with Paul Erlich that resources, far from running out, would become relatively cheaper as new extraction technologies, combined with the development of substitutes, made their supply outpace demand. Copper, for example, that Erlich thought would run out, was replaced by optical fibre cables for many of its uses, and now has a bigger reserve supply than it did then.

Harry was greatly amused when I suggested that although we’d probably never construct the “Transatlantic Tunnel” he wrote about in another of his stories, we might well bridge the Bering Strait and go overland to America the other way round.

The dystopia of “Soylent Green” never came about, and almost certainly never will. The chances are that there’ll be enough food and resources produced by new technologies, including lab-grown meats and graphene. And we won’t need to recycle the bodies of dead people into nutritious protein blocks.

How to know someone's away with the fairies

It can be worth a little checking of a claim against reality. Just to see whether the claim has any basis in that reality that is. So it is with this from Jean-Luc Melechon in France. Is this a reasonable set of insistences?

Europeans can insist environmental rules be respected everywhere: that not more is taken from nature than she can replenish. We can abandon pesticides, which kill biodiversity, immediately. We can decide to eradicate poverty, guarantee a decent wage for everyone, and restrict the income gap to stop inequality. We can extend women’s rights.

We can bind the hands of those who steal by tax evasion, those who misappropriate thousands of billions of euros every year.

It sounds rather colonial really to insist that all out there must do things as we insist they should. Still, we did it before no doubt it could be done again. We can’t stop using pesticides immediately - we’ve not enough land. Organic farming does require more land per unit of food produced and there simply isn’t enough of it to both leave some for nature and keep all of us alive. Europe has eradicated poverty - barring unfortunates in the grip of mental or addiction problems there is no one on the continent at all living in the usual international or historical definition of poverty, that $1.90 a day. Quite how we restrict the income gap is unknown and we have, do and are, extended women’s rights.

It’s the tax number which is easiest to compare in detail though. thousands of billions of euros is trillions. And the idea that there’s trillions in tax evasion just doesn’t match up to that reality. We can test this in two ways.

Quite the most expansive estimate - very expansive indeed - is from Richard Murphy and that’s below €900 billion for the entire EU. Given that his estimates of the UK gap are well over three times those of HMRC we should take that as being well over any realistic upper limit.

The other way to look at this is to note total tax revenues in the EU. Around and about €5 trillion a year. Trillions means at least two such, possibly more. And we really don’t think that there’s room for government to be collecting another 20% or more than they already do. There’s not room in GDP for them to be taking that much.

Sure, this is just one detail in a flood of rhetoric. But if one particular claim is as obviously wrong as this we don’t need to pay attention to the rest. It is all, obviously, just that rhetoric, not an actual analysis of anything useful.