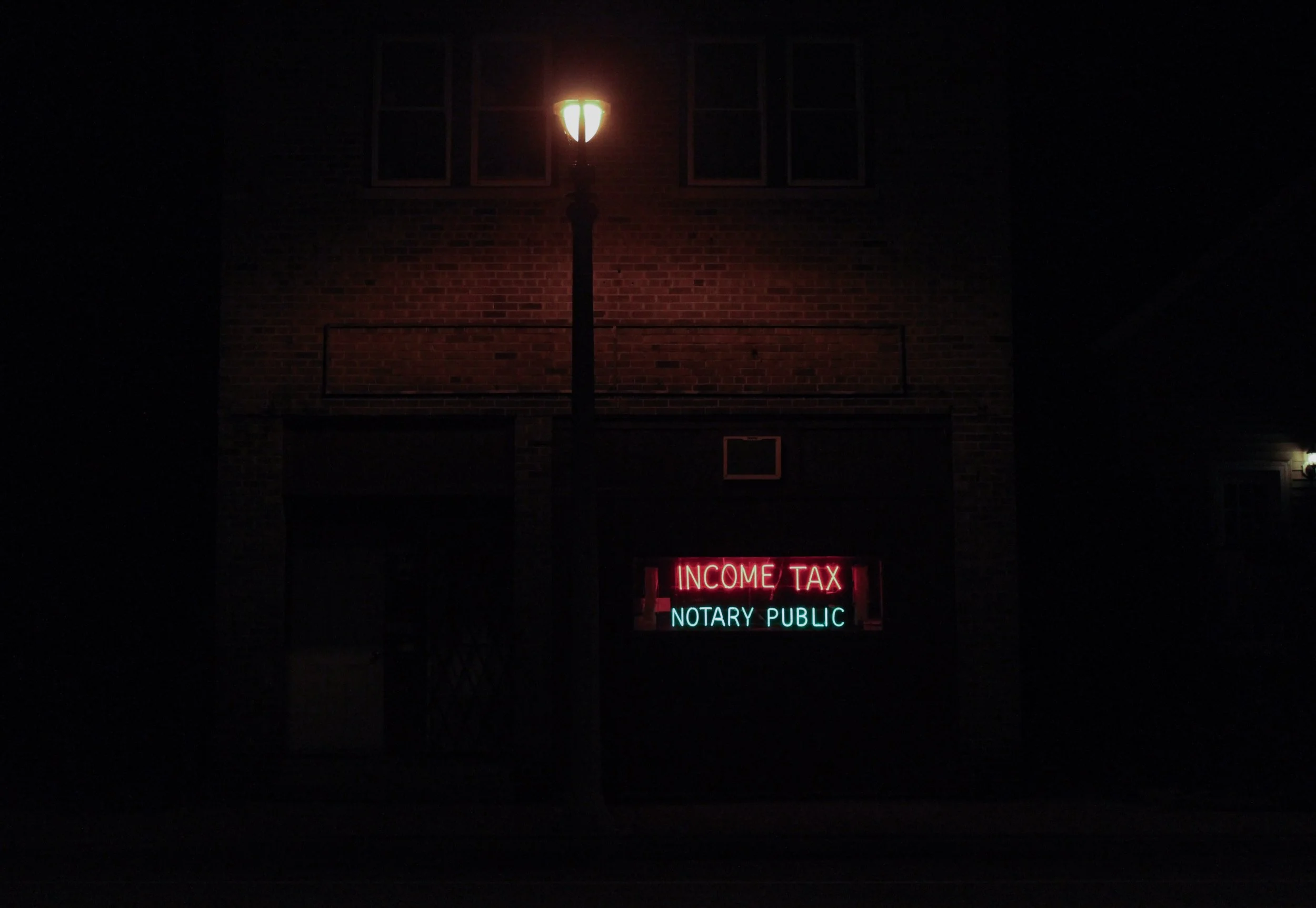

Why restaurant owners obsess about seemingly minor changes in the minimum wage

On the one side we’ve the people complaining that restaurants don’t pay great wages. Often enough not “living” wages. But, but, they’re big businesses with decent cashflows. They charge, £10, £30, just for a meal that can be cooked at home for pennies! Of course they can afford to pay decent wages!

On the other side we’ve those who understand the realities of the business. Margins are tight, there’s a great deal of competition - much the same statement of course - and profits rare. Thus wage levels are obsessed over.

A little data here. Sure, it’s about Washington DC but London won’t be much different:

CP: Some D.C. restaurants are celebrating their 25th and 30th anniversaries. Is there hope for restaurants opening in 2019 to have that kind of lifespan?

MG: It’s rare. One percent of openings last that long. I think a 15-year run is something to be damn proud of. I would love if any of my clients or people I know in the business have a good 10 years with a five-year option.

That’s success.

CP: What are some of the most common financial missteps new restaurants make that can get them into trouble quickly?

MG: The main reason businesses close quickly is because they undercapitalized. They thought they could open a restaurant for $1 million, but they end up spending $1.1 million. The business didn’t take off at the beginning. Now they have all these creditors coming after them. The construction guy didn’t get his final payment. The architect didn’t get his final payment. Everyone’s getting nervous. You’re scraping every dollar that comes in. There are a lot of businesses that can’t weather that. That’s the reason a restaurant turns in three years or less.

That’s the average experience. To try and fail within three years.

Now does it make sense why restaurants obsess about wage levels? Care deeply about 30% of their costs?

Good things from St Patrick’s land

St Patrick’s Day is celebrated on March 17th, the traditional date of his death. Since he is the patron saint of Ireland, people celebrate the country as well as the man. Some of the revelry borders on the kitsch, with giant green felt hats emblazoned with Guinness logos, and celebrations of leprechauns, Ireland’s “little people.” I was once in Chicago on the day, and saw the city’s fountains turned bright green, and the bars serving green beer (which looked wrong).

Patrick himself, after he was kidnapped from Britain in the 5th Century aged 16, and made to work as a slave in Ireland, later returned to bring Christianity to the island, it is claimed. He is supposed to have driven the snakes out of Ireland, but there is no evidence that there ever were any, and the story may be a coded reference to driving out the Druids who practised the ancient Celtic religion.

There are many good things to celebrate about Ireland, apart from its rain, but two in particular stand out. One is the tax exemption on creative artists, introduced by Charles Haughey in 1969. Originally it exempted income earned by Irish writers, composers, visual artists, and sculptors altogether from income tax, but the canny Irish Treasury thought it was costing too much in revenue foregone, and it now only exempts up to €50,000.

The scheme has encouraged several high-profile people in the "creative industries" to settle in Ireland, while also nurturing home-grown talent. Anne McCaffrey and Harry Harrison, famous SF writers, became Irish to take advantage of it, and part of its legacy is the large population of immigrant artists the scheme has persuaded to become Irish residents. Would-be claimants have to apply for it, and gain exemption if the Revenue deems their work to be original and creative, and recognized as having cultural or artistic merit. It has boosted Ireland’s reputation on the world’s cultural map.

Another reason to celebrate the Emerald Isle is its attitude to Corporate taxation. Its headline rate of 12.5% on trading income is among the lowest for developed countries, and encourages foreign firms such as Google to locate there. It is central to Ireland’s economy, with foreign firms paying 80% of Irish corporate tax, employing 25% of the Irish labour force, and creating 57% of Irish non-farm value addition.

The headline rate understates the value to foreign firms that locate there. Multinationals pay an effective tax rate of under 4% on global profits "shifted" to Ireland, via Ireland's global network of bilateral tax treaties. Ireland has a complex set of Irish base erosion and profit shifting ("BEPS") tools that enable firms to achieve these lower rates by moving their profits through Ireland.

Furthermore, because these schemes favour intellectual property rather than physical goods, almost all foreign multinationals in Ireland are from the industries with substantial IP, namely technology and life sciences. This puts Ireland at the forefront of modern technology. The EU resents and resists Ireland’s policy, however, and is bringing forward a plan to end national vetoes on tax policy.

In the meantime, though, we have two reasons to celebrate Ireland, and both involve the attraction of low taxes. One draws in cultural talent, and the other brings in international business. So here’s wishing a happy St Patrick’s Day to our neighbours and to the world at large.

Why is this heartbreaking?

The Telegraph tells us that:

Kingfishers, otters and swans are being forced to dodge plastic in Britain's rivers, the first images from a nationwide river survey have shown.

The University of Exeter and Greenpeace are currently testing river water at 13 sites nationwide and analysing plastics found there.

Images taken during sampling show otters swimming alongside plastic bottles, voles eating plastic, and plastic in the nests of swans, moorhens and coots.

The headline telling us:

Heartbeaking images show otters and kingfishers living alongside plastic in British rivers

Why is this heartbreaking?

One advantage of maturity in years - but not too much of course, given the effect upon memory - is that ability to recall what we used to worry about. Which was that Britain’s waterways were so polluted that we didn’t have any wildlife. The 1950’s Thames was dead water, not a living thing above the size of E. Coli in it below about Teddington or so. Rivers of London is even a novel using this as its basic underlying conceit. Now we’ve got salmon in there. One of the things about Tarka The Otter was the complaint that such magnificent - if often vicious hunters - creatures would be no more than decomposing corpses soon enough.

OK, we’ve got the wildlife back and it has to dodge plastic. And?

The point being that sure, we’re using more plastic than we used to. These past few decades have indeed seen a significant rise in our use, our release as waste into that environment. They’ve also seen a massive diminution of all the other wastes we used to splay about. The net result - net note - is better. Why is this heartbreaking?

It’s even possible that we’d like there not to be the plastic out there as well. But as we consider what we’re going to do about that we must indeed recall that the current solution is vastly better than the one we had before we all started using plastics. Maybe it’s all just a coincidence, maybe it’s a correlation and there’s no causality to it. But whether or not that’s true is the thing we’ve got to consider.

It’s at least possible that our plastic use, along with it littering the waterways, is why we’ve actually had the swans, the coots, the otters, back. And if that’s true then what should we do then?

Again, not to say that is true. Only that that’s the question to consider.

“Father of the Constitution”

James Madison was born in Virginia on March 16, 1751. He was to play a pivotal role in developing the Constitution of the United States, which replaced the Articles of Confederation that were ratified after the War of Independence. Madison thought the Articles, in leaving most power to the state legislatures, had left the national government too weak to raise funds or to maintain an adequate national army.

Madison wanted a federal government established, with checks and balances that divided power between the legislative, executive and judicial branches. His “Virginia Plan” formed the basis of the Constitution. In the run-up to its ratification, he co-authored a collection of 85 articles and essays with his colleagues Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. These were dubbed “The Federalist Papers,” and sought to win the argument for a federal government.

Madison’s early drafts of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights earned him the nickname, “Father of the Constitution,” though he modestly stressed the role played by others. The Bill of Rights, a group of 10 amendments to the Constitution, gave written guarantees for such issues as freedom of speech and religion, the right to bear arms, and the right not to be forced to testify against oneself. These guarantees, written by Madison in response to the misgivings that some held about the proposed Constitution, succeeded in having it ratified.

The United States thus became a country with a written Constitution, one governed by laws rather than by men. The rights that it enshrined are no less relevant now than they were then, and have lasted through the 230 years that have elapsed since. The model set out by that Constitution is that the people can be protected if power is dispersed, and if lawmakers themselves come under the law.

Madison himself was honoured as one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, and was elected as its fourth president, serving from 1809 to 1817. He left a name that shines bright in the annals of liberty.

Well, yes, this is how it works, taxation makes people poorer

It is entirely true that some of the things government does makes us, all or some people, richer. Equally true is that the act of taxation itself makes those being taxed poorer. So this is not exactly a great surprise:

Stealth taxes are forcing more people into higher tax brackets and cutting child benefit payments because the thresholds are not moving in line with inflation or wages, the Institute for Fiscal Studies has warned.

As the ageing population puts more strain on the health and pensions budgets, its likely the Government will have to impose significant further tax rises on high and middle earners in the years ahead.

Relying on inflation to pull more people into higher tax brackets means families are paying more tax even though their incomes have not risen in real terms, leaving them worse off overall.

Increase the taxation of the population and the population will be, as a result, poorer. Yes, again, it’s worth considering what the cash is then spent upon but this is the effect of the taxing itself - people have less money themselves, they are poorer.

The actual mechanism is called fiscal drag. Don’t upgrade taxation brackets by earnings growth say. Earnings do grow, generally speaking, in real terms over time. So holding the brackets static captures ever more people at ever lower percentages of average income. A more extreme form is not even to upgrade by inflation - Gordon Brown did that with the personal allowance at least once.

Our own - successful - campaign around here to raise the personal allowance to £12,500 was at heart just a reversal of decades of this fiscal drag. There was a time when only those on greater than median earnings entered the income tax net. Now it starts before even a full year of work on the minimum wage. And that’s after the near tripling of that personal allowance - that’s the effect of fiscal drag over time.

The IFS’s basic contention here, tax people more and they’re poorer, is uncontestable. Which does open up that question of why we keep trying to d so. It’s not a known aim of economic policy to make people poorer now, is it?

Clothes rationing ended long after the war

Clothes rationing ended on 15 March 1949. In World War II Britain, clothes rationing had been introduced in June 1941. Clothing materials were needed to produce the uniforms that were by then worn by a quarter of the population.

Most things were rationed in the drive to be more self-sufficient in the fight against Nazism. Petrol came first, then food was severely rationed. Everyone had to register at chosen shops, and was given a ration book with coupons. Shopkeepers were given enough food for registered customers. Would-be buyers took ration books with them when shopping, so that coupons could be torn out or cancelled.

In 1939 it was petrol. Then in 1940 bacon, butter and sugar were rationed. Then came rationing for meat, tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, eggs, lard, milk, and canned and dried fruit.

When clothing was rationed, it was calculated to provide one change of outfit per year, with more coupons for growing teenagers. The ration was based on how much labour went into a garment, and how much material was used. A dress could take 11 coupons, whereas a pair of stockings took only 2. Men’s shoes took 7 coupons, while women’s shoes were only 5. In 1945 an overcoat needed 18 coupons; a man's suit, 26–29, depending on the lining.

No coupons were needed for second-hand clothing, but prices were fixed. The ‘Make do and Mend’ campaign, supported by poster advertising, urged people to repair rather than replace their clothing, thereby engendering a generation of skilled repairers.

In 1942 clothing austerity measures were introduced to limit the number of buttons, pockets, pleats, and decorations on clothes, and shoes and boots became hard-to-get items. The ‘Utility’ brand denoted basic, government approved clothing. As a child, I wore a ‘Utility’ raincoat.

Rationing led to black markets. ‘Spivs’ offered additional non-rationed supplies to those who could afford it. This was a lucrative industry, and the maximum five-year jail sentence for being a ‘spiv’ was not much of a deterrent.

After the end of the Second World War, rationing continued. In some cases it became stricter after the war. With many men still in the armed forces, an austere economic climate, and a centrally-planned economy under the post-war Labour government, resources were not available to increase production and imports. Strikes often made things worse. Cheating became widespread, and often the ration books of the dead were kept and used by their relatives

In 1950 the Conservative Party played upon public resentment at continued rationing, scarcity, controls, austerity and government bureaucracy. People had seen how the socialist policies of the Labour Party had failed to alleviate shortages and were ready for alternatives. The Conservatives, under Churchill, staged a political comeback with the slogan “Set the people free,” and won power in the 1951 general election. Their appeal was especially effective to housewives, who found shopping conditions harder after the war than they had been during it.

It was alleged that clothing rationing ended because attempts to enforce it were thwarted by massive illegality, including black markets, unofficial trade in clothing coupons, many forged, and bulk thefts of unissued clothes ration books. Either way, its ending in 1949 came too late to save the Labour government. People were fed up of shortages and rationing, and turned to the Conservatives to end them.

A small test of how the state expands - that period poverty charity

Now that the mistake has been made to hand out sanitary products for free in schools we can use this as a little test of one of Milton Friedman’s contentions. That there’s nothing so permanent as a temporary government program.

For Phil Hammond has, along with that freebie stuff, announced that tampons etc will be VAT free the moment we are free of Brussels and thus able to make them so. OK, we’re fine with that, both that they should be VAT free and also that domestic taxation should be something decided domestically by the domestic legislature.

It’s just that the VAT collected has been, for some years now, sent into a special fund to pay for special projects:

The government has already pledged to remove VAT on sanitary products – the so-called “tampon tax” – when the UK leaves the European Union. Currently it channels the revenue it raises to good causes.

Now that the problem has been entirely solved - both the VAT and the schools poverty thing - how many of those good causes are going to be defunded? And how many will end up being absorbed into some other funding stream?

It’s a good test of that contention, isn’t it? The state lingers on, as bureaucracies tend to, even when we’ve entirely solved the issue by other means. We are going to be able, here, to test that contention in detail.

Karl Marx – failures and successes

Karl Marx died 134 years ago, on March 14th, 1883. His work was hugely influential, though not in the way he conceived. He interpreted history in terms of class struggle, believing that societies develop though conflict between those he called the bourgeoisie, who controlled the means of production, and the proletariat, who provided the labour that made the products.

Marx followed the labour theory of value, as had Adam Smith, holding that the value of goods lay in the labour it cost to produce them. The various inputs of production could be valued at the labour it had taken to make them. From this came his view of profit as “surplus value” that derived from exploitation, not paying the worker the true value of his product. The problem with this is that value is not a property that resides in object. It exists in the mind because people value things, and value them differently. We value things; they don’t have value. If nobody values an object, then it has no value, no matter how much labour it might have taken to produce it.

Marx also followed a Hegelian view of how change takes place. In Hegel’s view a state of affairs (the thesis), generates contradictions within it (the antithesis), and from a violent clash between the two, a new order emerges (the synthesis). This, in turn, becomes a new thesis, and the cycle is repeated. History, on this model, moves in triads, though a series of violent clashes. Marx thought that capitalism would and did generate internal contradictions, such as the class-consciousness that comes from putting workers together in factories. From these would come the violent clashes that would ultimately see capitalism replaced by socialism. Revolutionary violence was the force driving change.

It is a pity that Marx had not given more attention to the Darwinian view of change. His “Das Kapital” was published in 1867, eight years after Darwin’s “The Origin of Species.” Marx had read Darwin, and admired the way he accounted for human origins without recourse to religion. What he didn’t spot was the mechanism of change, by which innovations gradually over time spread to become the new norms. It provides a more fruitful and convincing account of how human societies develop and change, by evolution rather than revolution.

On the Marxist analysis, the climactic struggle and outcome should have come first in the most advanced and developed economies, those in the fullest and final stage of capitalism. It did not, of course, because Russia was not among them. Lenin simply did what was needed to win power, and rewrote the book afterwards. Mao later did the same in China. Neither case followed the Marxist model of historical progression.

Where Marx did succeed was in pointing to the way in which changes in the economy, specifically in the means of production, lead to changes in its social organization and, indeed, to a society’s culture and its laws. In his 1847 “Poverty of Philosophy,” he wrote, “The hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill society with the industrial capitalist.” Marxists tend to over-egg this insight if they claim this to be the sole cause behind social change, but other historians regard it as one useful key, among others on the chain, as they seek to unlock and understand why the past happened as it did.

The twin tub washing machine at £1,960 a piece

It’s interesting what can be learnt from the obituaries page. A man, John Bloom, made - before he lost it again - a fortune from selling twin tub washing machines to the masses. A proper fortune, Mayfair, Rolls Royce and all.

He had a flat in Mayfair in the heart of London, a 150ft motor yacht that had a lift linking the bridge to the master bedroom, and a Rolls-Royce Phantom in which, for a publicity stunt, he gave the Beatles a ride down Fleet Street.

Such inequality, such capitalist exploitation of the toiling masses.

Except, well:He had done it by shaking the “white goods” industry to its very foundations in what had become known in the press as the “washing machine wars”. His approach was simple yet revolutionary. His company, Rolls Razor, cut out the middle men, the retailer and the wholesaler, by selling 6,000 washing machines a week directly to customers at a drastically reduced rate of almost half-price.

...

In 1958 he advertised the Electromatic twin-tub washer-spin dryer at 39 guineas (£980 today), undercutting the high street retailers by 50 per cent.

Who got the better end of the deal there? In aggregate? The 6,000 households a week saving near £1,000 each or the bloke with the fancy lifestyle? Clearly, it’s that £6 million a week being saved, isn’t it, for no one at all is thinking that Bloom was off with £6 million a week himself.

As it always is with this entrepreneurial capitalism of course. Most assuredly those who succeed gain that luxury. But it only happens if they’re making their customers vastly better off by their actions. For, of course, the consumers won’t be lining up to buy the stuff unless it does make them better off.

And doesn’t the thought of the £2,000 washing machine set just sting these days?

When the barbarous relic hit $1,000

On March 13th, 2008, gold prices on the New York Mercantile Exchange passed $1000 per ounce for the first time in history. One reason gold is so valuable is that there is not much of it about. The world annual gold production would make a cube of just 14 feet on each side. All of the gold ever produced by anyone throughout history would only reach one third of the way up the Washington Monument.

Another reason for its value is its comparative incorruptibility, which is one reason behind its almost universal acceptance. France’s President de Gaulle, who favoured a return to currencies fixed to the price of gold, in a 1965 press conference sang its praises: “That which is immutable, eternal.” He resented the influence that the dollar gave to the US, and he wanted a return to the gold standard, which would not be the political instrument of any one country.

A more surprising “gold bug” was ex-Federal Reserve Chairman, Alan Greenspan. In 1966 he wrote "Deficit spending is simply a scheme for the confiscation of wealth. Gold stands in the way of this insidious process.” He later admitted he was in a tiny minority at the Fed who favoured a return to the Gold Standard.

In modern times the lessons of Zimbabwe and Venezuela point to the catastrophic effects that can follow when a corrupt or incompetent government finances its lavish spending by printing more of its currency.

The Gold Standard favours the countries that have gold deposits, but it has the advantage of making it difficult for governments to inflate prices by expanding the money supply. It engenders long-term price stability because the money supply can only grow at the rate at which gold is produced. Inflation can come, though, if a major new source of gold is developed, as happened with Spanish gold from the New World, or with various “gold rushes.”

On the other hand, a fiat currency, one backed by the government that issues it, can be increased in supply at the rate of growth in the economy. Some economists think that limits to the supply of gold act to limit the economy’s ability to supply the capital needed for growth. John Maynard Keynes said in 1924, “In truth, the gold standard is already a barbarous relic.”

Furthermore, some point out that a fiat currency gives a country the ability to handle economic shocks. The fact that governments could control the money supply in the wake of the 2008-09 financial crisis is said to have helped prevent even worse effects from following.

The rise of gold through the $1000 per ounce barrier happened some years after Chancellor Gordon Brown sold about half of the UK’s reserves of it. Between 1999 and 2002 he unloaded about 395 tons of it at an average of about $275 per ounce. By announcing his intention in advance, he virtually ensured rock bottom prices. It subsequently rose to over four times that level, but the currencies he traded it for have not done as well.