We seem to have solved that diabetes problem then, no need for more laws

A standard point around here is that the existence of some problem does not justify yet more action to solve that problem. What we should - and need - to be doing is to look at how much of that problem remains after whatever it is we do to reduce it. Only then can we see whether we need to be doing more, less, or just carry on, in our solution to the ailment.

For example, looking at market incomes tells us nothing about how much tax and redistribution should be done to reduce inequality. It is only looking at post-tax and post-benefit incomes, and by preference moving over to looking at consumption not income, that can possibly tell us that more needs to be done or not. Climate change may well mean that we’d prefer there to be fewer coal fired power stations in the future. But that requires our looking at how many such we’re going to have in the future, not assuming that matters will remain as they are. Given that new coal fired investment is plummeting, solar being the new investment of choice in many places, shows that much of what we need to do about climate change has already been done. Inefficiently, possibly we didn’t even need to do anything anyway, but within the terms of the IPCC’s warnings much of it has indeed already been done.

Which brings us to that other terror of the age, the soaring diabetes rate:

The number of diagnoses of type 2 diabetes has fallen in an ‘encouraging’ sign, the charity Diabetes UK has said. Although three people are still being diagnosed every three minutes the equivalent of 552 cases per day, it is 27 cases fewer each day than in 2016 when there were 579 every 24 hours, nearly one person every two minutes.

202,665 people were diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes in England and Wales in 2017, the most recent year for which statistics are available, down from 211,425 in 2016.

The charity Diabetes UK said they did not want to speculate on what the cause of the drop might be, but said they were still concerned about the large numbers of people developing the condition…

Sure, be concerned all you like. But what it shows is that it is possible to lower that rate without a sugar tax, without banning “junk food” adverts, without telling supermarkets how they may lay out their wares. It might even be that just telling people they might die if they don’t curb their consumption works.

You know, we humans might be ignorant - we certainly note there are things we don’t know about - but we’re also rational, we’ll respond to information and incentives.

Maybe it’s even possible that a full pile on to reduce the diabetes rate is justified. But that justification is and can only be valid if we look at what we’re already doing and only then muse upon whether we need to do more.

More importantly, that the diabetes rate is falling before all of those further curtailments of liberty that PHE is insisting upon shows us that we don’t have to give up freedom in order to gain that falling diabetes rate. So, well, let’s not give up liberty then, eh?

April Fools’ Day

April 1st is traditionally a day devoted to pranks. The etiquette suggests that this is a morning thing, and that the pranksters should come clean at noon. There have been many celebrated ones that achieved stardom. In 1957 BBC’s Panorama ran a short film showing spaghetti being allegedly harvested from trees. In 1969 a Netherlands state broadcaster, NTS, ran a feature about detector vans roaming the streets to detect TVs receiving without licences. It said the only way to avoid detection was to wrap the TV set in aluminium foil. Next day all the supermarkets sold out of foil, and record numbers sent in licence payments.

The ASI played one that unfortunately was taken seriously. We sent out a press release condemning the EU’s decision to ban all knives with blades exceeding 10cm, or 4ins, on the grounds that research had established that most knife crimes were committed with blades longer than that. We quoted the EU health and safety commission, Senator Faporillo, welcoming the new law. We quoted the head of the German Employers’ Association refuting the claim that thousands of new jobs would be created, saying that when this had been tested in a trial German town, the only new jobs it generated were for knife grinders shortening existing blades.

Senator “Faporillo” is, of course, an anagram of April Fool. Our intended giveaway was the comment we added from the UK’s Health and Safety Officer, announcing that the law would be rigorously applied when December 31st, the so-called “night of the short knives,” arrived.

Unfortunately, some of the media took it seriously and did some work on the story. The Mail spent time preparing to denounce the move. The Wall Street Journal rang up to ask, “This is a joke, right?” Worst was the Sun, who had prepared to make this their front-page story. They had telephoned the EU to ask Senator Faporillo for a comment, but were told he was out at lunch, presumably by some secretary unwilling to admit she’d never heard of him. When they asked us for a comment and were told it was a joke, they were angry that we had “wasted their time.” We could only apologize profusely, expressing sincere regret at the trouble we had caused. We had intended to amuse people, not to inconvenience them.

Having learned our lesson, we never again played an April Fools’ joke. The other lesson might be that there is no insanity that people believe the EU to be incapable of perpetrating. Even now I imagine someone deep inside Brussels is probably drafting for real the law we posted about in jest…

It's amazing what we don't get told at times

Phillip Inman tells us that it’s all very bad indeed, the manner in which “austerity” has been exported from the rich countries to the poor. The thing is, he uses Mozambique as one of his examples:

It is in this atmosphere that the west has turned away from even the most emotional pleading, such as the calls for Mozambique to be supported with a debt write-off following the devastation left by cyclone Idai. According to the IMF, Mozambique is among six out of 35 low-income countries in the region that are in “debt distress” – in default and unable to service outstanding loans.

Well, yes, very poor place, badly hit by that cyclone, very high debts too. Except, except, therre is more to this, something we should know:

Mozambique’s Minister of Economy and Finance, Adriano Maleiane, has said the country’s foreign public debt, until December 31, 2017, was $10.6 billion.

Maleiane said it is to date the highest debt to GDP ratio in Africa.

Speaking in parliament on Thursday, Maleiane said this amount includes bilateral debt, which is 4.6 billion, corresponding to 43 percent of total debt; alongside the multilateral debt contracted with institutions such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank (ADB) which is pegged at $4.2 billion, representing 39 percent.

The minister said the remaining part is commercial debt amounting to $1.8 billion, which the Mozambique admitted as previously undisclosed loans, much of which was spent on building a state tuna-fishing company and enhancing maritime security, a discovery prompted the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and foreign donors to cut off support, triggering a currency collapse and leading to a default.

“We are now only paying multilateral and bilateral debt. The commercial is not being paid, since, since 2016, we are in the process of negotiations.

Bilateral here means government to government. And as to why that commercial debt isn’t being paid?

Mozambique announced on Monday the indictment of 18 individuals in connection to the US$2 billion “tuna bonds” scandal that plunged the country into its worst financial crisis since independence.

The scandal is the borrowing of that $2 billion and the theft of it. What wasn’t directly stolen was entirely wasted. This being that debt which leads to the emotional pleading for a write off.

It’s fairly important to the point, isn’t it?

Sure, it could be argued that it’s an odious debt. The rulers simply stole it therefore the people shouldn’t have to pay it. We’d even be supportive - perhaps - if that was being so argued. But we’d insist upon emphasising the corollary, which is that certain poverty problems really are caused by the oligarchy being kleptocrats, not because we in the rich world are meanies for not sending even more money.

Which isn’t the point Inman is trying to argue at all, presumably why those facts don’t get mentioned.

UNIVAC makes history

On March 31st, 1951, Remington Rand delivered UNIVAC, the first commercial computer produced in the US, to the US Census Bureau. It competed with, and ultimately replaced, punch-card machines. It used about 5,000 vacuum tubes, weighed 16,686 pounds (7.5 tons), consumed 125 kW, and could perform about 1,905 operations per second. It sprang to fame in the 1952 Presidential election when, with a sample of just 1% of the voting population, it went against the pollsters' verdict for Stevenson, and correctly predicted instead a landslide for Eisenhower.

Although it originally sold at $159,000, the UNIVAC's price increased until it reached between $1,250,000 and $1,500,000. A total of 46 of them were eventually built and delivered. No-one foresaw at the time that computers would become so inexpensive, so light, and so powerful. Indeed, many famous people have made wildly inaccurate predictions about the march of technology. Thomas Watson, president of IBM, said in 1943, "I think there is a world market for maybe five computers." He was probably thinking of ones that weighed tons and used thousands of vacuum tubes.

Ken Olsen, founder of Digital Equipment Corporation, remarked in 1977, "There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home." Yet within a generation, virtually every home in a developed country had one, and a few years later virtually every child in a developed country had one in his or her pocket. There have been just as wrong predictions made by others. In 1998 Nobel laureate Paul Krugman confidently asserted, "By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s." He is as confident and as wrong about most things he writes about in the New York Times.

People today make stark predictions about the likely impact of technological innovations, usually about their effect on jobs. Typewriters reduced the demand for scribes to near zero, and electronic calculators cut the jobs of comptometer operators. No doubt UNIVAC and its successors did away with Hollerith and other punch card machines, together with the experts who operated them.

But always in the past, innovations such as these have created many more jobs than they have cost, and have raised wages and living standards with the increased productivity they make possible. There is no reason to suppose that the advent of Artificial Intelligence, which doomsayers tell us will threaten many jobs, will be any different. It will increase productivity and wealth, and it will lead to new jobs being generated.

If someone doubtfully asks, "What kind of jobs will be created?" The answer is that this is unpredictable. We simply don't know what human tastes and needs will be, or how people will choose to spend their new-found wealth and leisure. Many of today's jobs simply didn't exist a generation or so ago. And many of the future's jobs simply don't exist today.

Factortame probably did have something to do with Brexit, yes

Factortame was an uninteresting case over who could access fishing quotas. Factortame was also a hugely important case concerning who rules? The answer being that it’s them over there, Brussels, which does. This does indeed have something to do with where we are now with Brexit:

Carl Gardner, a former government lawyer who has negotiated for the UK and defended the government in the European courts, says that while the decision came as a shock to the British legal system, it came as “even more of a shock to the political system”.

He suggests that along with the Maastricht Treaty in the early 90s, the decision in Factortame helped stoke Euroscepticism.

“The experience made politicians more defensive of sovereignty,” he suggests. He also believes the “scars Factortame left” are reflected in the Human Rights Act, which carefully avoided letting judges disapply acts of parliament. “If we’re tempted to think we’ll soon be free of Factortame, we’re wrong,” he says. “Any withdrawal agreement is likely to prevail over our own law.

“I’m not sure we’ll ever hear the last of Factortame, which leaves as permanent a mark on our law and politics as any case ever decided by the court.”

The specific point being:

Crossbench peer and barrister Lord Pannick says that Factortame was “the most significant decision of United Kingdom courts on EU law”. “It brought home to lawyers, politicians and the public in this jurisdiction that EU law really did have supremacy over acts of parliament,” he says.

Before Factortame that fact had not been widely understood, even though it had been decades since the UK had joined the European Economic Community in 1973. After the judgments, says Pannick, there was no longer any excuse for ignorance.

This is a fairly important point, they rule us, not we rule us.

Sure, it’s possible to go on and say that, say, the European Parliament is only a larger us ruling a larger us. But that’s then a Parliament that cannot initiate legislation, really only has the power to delay. That is, rather less power than the House of Lords does in the UK. We usually tend to think we the people should have rather more protection from the executive than that.

But it is true that Factortame brought home to us all that it’s EU law which is paramount, this isn’t simply a treaty or agreement, it’s an imposition of sovereignty, a reduction of our own.

It’s even possible to argue that this is as it should be it’s just that an awful lot of people don’t agree. Which is rather how we got to where we are today.

President Reagan survived a would-be killer

On March 30th, 1981, barely nine weeks after he took office, President Ronald Reagan was shot as he left a meeting at the Washington Hilton Hotel. The would-be assassin fired six shots, wounding three people, but missing the President. One of the shots ricocheted off the limo as Reagan was hustled inside, wounding him in the lung, and missing his heart by one inch. Reagan was close to death as he underwent emergency surgery, but he survived and recovered quickly, returning to applause at the Oval Office within four weeks. Had he not survived, history would have been very different.

Without Reagan there might not have been the tax cuts that revitalized the American economy and ushered in a period of steady growth that saw the average US citizen's standard of living rise. Had he not had his eight years in office, America might not have seen 16 million new jobs created. It might not have seen the inflation rate drop to 2.5 percent.

Surely no other president would have embraced the Strategic Defence Initiative, raising the prospect that deterring Soviet aggression might be replaced by a defensive capability, with the technological ability to intercept and destroy Soviet missiles. Ultimately it precipitated the collapse of the Soviet empire, which could not compete technologically nor militarily with the US.

Reagan was thought to be something of a hawk on foreign policy, giving evil its proper name and standing up to it. To counter the Soviet's SS-20 missiles, he deployed Pershing II and Ground Launched Cruise Missiles in Europe, to bring the USSR to the negotiating table to sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. His strengthening of the US military with modern weapons and equipment is believed to have played a key role in bringing about the final collapse of the Soviet Union and ending the tyranny of Communism. He won the Cold War.

His personality played no small part in reinvigorating and uniting America after years of discord. He was known as the "Great Communicator" for his ability to put ideas across in a jargon-free, non-patronizing way that ordinary Americans could relate to. He unashamedly championed the ideals of the Founding Fathers, including patriotism, and his optimism restored to Americans their faith in themselves and their country.

Had one of the six shots fired that March day been more accurate, the world would have been different. But Reagan was saved, and so was the world's future.

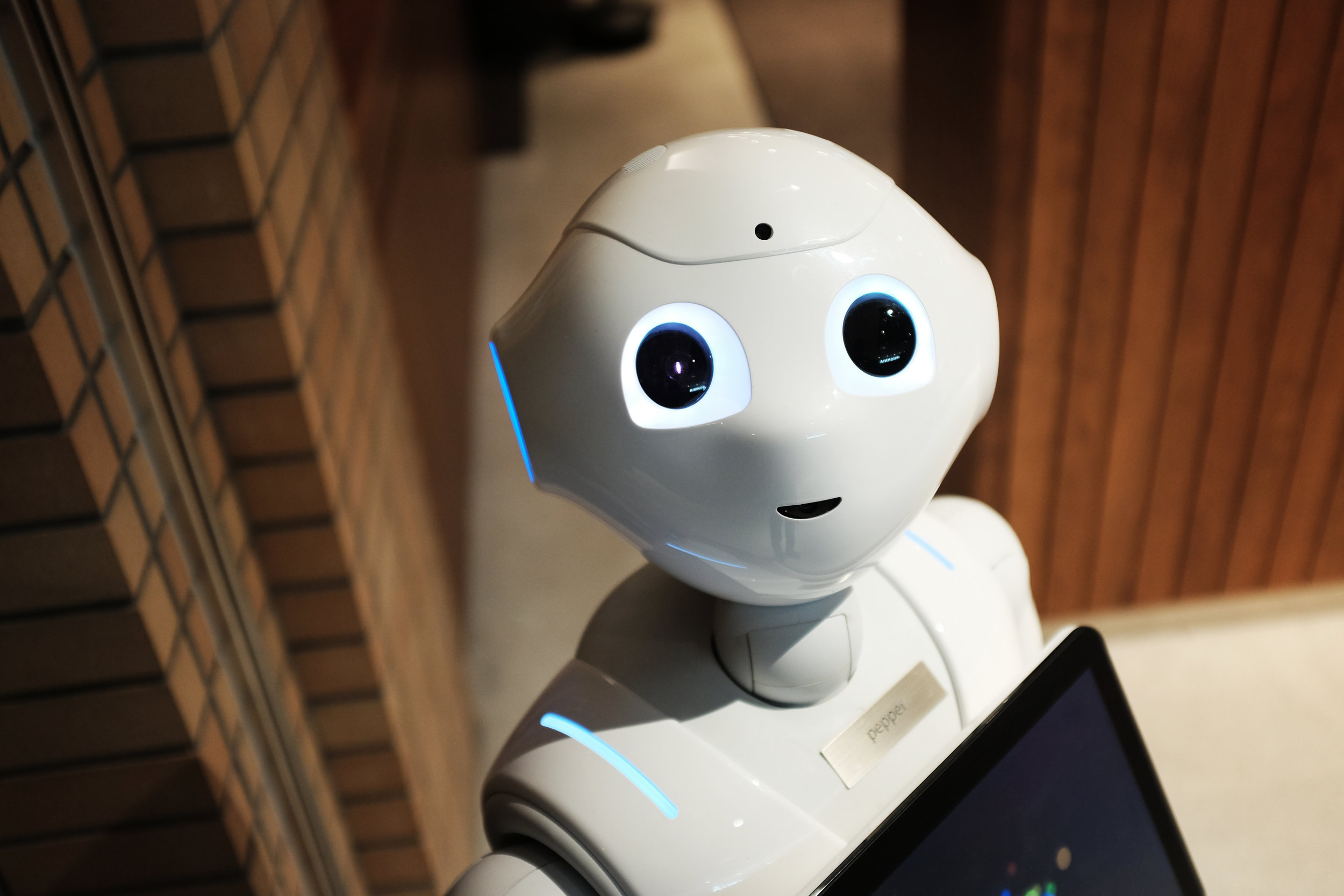

The problem is that the algos, the robots, the AIs, they should be biased

We’ve a fundamentally flawed movement over there on the left concerning this brave new world of algorithms, robots and artificial intelligences. For there’s an insistence that they must all be coded so as to be non racist, non-discriminatory along any of the currently fashionable axes. This being entirely the wrong idea of course.

The root of the demand is that age old insistence that we can make the world to be something other than it is. As Brecht said, elect another people, or await that New Soviet Man that would actually make socialism work. That’s not actually how human societies work:

For people directly harmed by the fast-moving and largely unregulated deployment of AI in the criminal justice system, education, the financial sector, government surveillance, transportation and other realms of society, the consequences can be dire.

“Algorithms determine who gets housing loans and who doesn’t, who goes to jail and who doesn’t, who gets to go to what school,” said Malkia Devich Cyril, the executive director of the Center for Media Justice. “There is a real risk and real danger to people’s lives and people’s freedom.”

The point being that the AIs and the rest are to be used as tools to aid in managing and operating our society. Thus, far from being pure and unbiased, they must incorporate those biases which exist.

No one in this debate - most especially the people doing the worrying here - is going to try to say that there are no such biases among us humans. Nor that society as currently structured does not incorporate them. But that in turn means that any tools we use must reflect the current society we’re trying to manage, not some some possibly glorious one where humans aren’t humans.

Think on it. To use an algo to describe and manage an unbiased society is going to have that same connection with reality as the Soviet food manager allocating the harvest that the just shot kulaks haven’t collected.

The time to be insisting upon unbiased software is when the society and the people being described are unbiased. Sure, we hope for that too. But coding in what we’re not isn’t going to aid in managing what we are now, is it?

When the Dow first topped 10,000

Between 1995 and 2,000, many investors were keen to get in on the rapidly developing internet technology sector, and new companies were set up and funded on a daily basis. The period has become known as the “Dot-com bubble.” On March 29th, 1999, the Dow Jones Index passed 10,000 for the first time in history. Initial Public Offerings attracted huge sums, with successful launches for Netscape, Yahoo and Lycos hitting the headlines and spurring investors into backing other startups.

The bubble was fed by low interest rates (cheap money) and market exuberance. Anything with a “.com” after its name was thought promising, and people didn’t want to miss out on the future. Most such companies offered free services and had no earnings, but investors expected them to generate profits in the future, and ignored traditional measures such as the price-earnings ratio. I had one friend who spent huge sums building up such a company, talking about the value of his ‘lists’ of addresses, but without any means of commercializing them. It was typical of the “growth over profits” approach that characterized such enterprises.

The bubble burst, of course. Alan Greenspan raised interest rates, and companies that had borrowed heavily found themselves insolvent. When Barron’s ran a cover story in March 2000, entitled "Burning Up; Warning: Internet companies are running out of cash – fast," alarm bells rang and investors rethought their approach. Many big-name companies, including ones that had been valued in billions at recent IPOs, went broke and folded. In 2 years the Nasdaq dropped nearly 80%. Amazon and e-Bay survived, but most didn’t.

It was by no means the first such bubble, and will not be the last. Among the famous ones are the tulip mania in the Netherlands from 1634-1637, in which single bulbs were selling at one stage for the price of a house.

The South Sea Bubble (1716-1720) was in the shares of the South Sea Company, given special trading rights in South America by the British government. Speculation and rumour vastly overstated any actual potential.

The British Railway Mania of the 1840s was an earlier case of over-exuberance toward the business prospects of a new and disruptive technology.

The 1929 US Stock Market Crash came after a period of peace and prosperity sent share prices rocketing as new technologies, such as radio, motor cars and aeroplanes, were making a commercial impact.

The common factors underlying most bubbles seem to be an over-exuberance toward something new, rather than a cold calculation of its likely potential. It happens because it is very difficult to evaluate the likely impact of innovations. They take us sailing into new and uncharted waters, with optimism filling the sails. The only antidote to this exuberance is realism, and the hard calculations about cash flows and likely returns.

If only Waterstones staff read the authors they sell - say, Adam Smith

At least we assume that Adam Smith’s works are sold in Waterstones. Even if not it would be worth the staff currently complaining about their wages having a read. For one of the points that Adam Smith makes is that all jobs pay the same.

Not, obviously, all and exactly, there’re skill levels, training and so on to think about. But more generally, the conditions, the enjoyability, the stimulation, of a job are going to be negatively correlated with the cash pay for that job. This is why 99% (OK, perhaps 90%) of all would be actors make nothing from it ever, as prancing on the stage is most enjoyable therefore there are many who’ll do it for no cash. Dustmen don’t make good money because it requires great skill and application but because it’s a noisesome line of work, dunnikin divers even more so.

This was, rightly, pointed out some 250 years ago or so. Not too much to expect people to have grasped it by now?

Waterstones’ much-celebrated return to profitability has been engineered by Daunt, but built on the labour of booksellers, much of it inadequately remunerated and unrecognised. My experience with the company is far from unique, because for years now booksellers have had to take on additional workload and responsibilities as staff numbers (both on the shop floor and at head office) have decreased, almost all of it uncompensated. No longer do they simply shelve, operate tills and talk to customers about books. They are expected to be operations managers, security guards, childminders, baristas, cleaners, graphic designers, events managers, social media wizards and much more besides, but at a fraction of the pay for which those jobs would normally be contracted out. Theirs is the tireless effort by which the company remains afloat, and to say – as Daunt has – that a stimulating job should be a reward in itself is not simply patronising, it is exploitative.

You can call it exploitative if you like, you can call it Aunt Sally if you prefer. But it’s a simple truth about human beings that stimulating and interesting jobs are going to pay less than horrible noisesome ones requiring the same skill and attention. Because interest and stimulation are part of the pay, filth and unenjoyment things that must be compensated for.

And if you don’t like the deal then the British economy does contain some 30 million odd other jobs, some in that marketplace perhaps offering a more favourable to your own tastes blend of conditions and money than bookselling?

Jim Taylor is a writer who also manages an independent bookshop in Edinburgh

Or maybe not for someone who moonlights in order to retain that job as a bookseller?

A vote that saved a nation

March 28th, 1979, was one of the most exciting evenings in postwar British politics. It was 40 years ago that a no confidence motion was debated, one that everyone knew would go down to the wire. The Labour government of James Callaghan was soldiering on, supported at times by Liberals and Scottish Nationalists. He’d been expected to call an election in the autumn of 1978, but had held on, hoping for ae economic upturn. Unfortunately for him, widespread industrial unrest shut down many services in the “winter of discontent,” and Labour’s popularity fell.

On March 1st, a Scottish referendum on devolution had failed to break the 40% threshold, and the SNP turned against the government when it declined to bring in devolution. Tory leader, Margaret Thatcher put down a motion of no confidence on March 26th, and frantic bargaining went on for 3 days as the government tried to cobble together a majority. It gained some Ulster Unionist and Plaid votes by promising extra funds for their areas, and it looked as though they might just make it when they persuaded Irish Independent Frank McGuire to come over for the debate.

The debate was covered live on the radio, and was broadcast in many pubs throughout Britain. Everyone held their breath as the division came. The Tory whip boomed out the result: “Ayes to the right 311, Noes to the left 310.” No confidence was carried. My friends reported that a great cheer went up in pubs across the country. Callaghan made a dignified response: “Mr Speaker, now that the House has declared itself, we shall take our case to the country.”

It was a hard-fought campaign until Polling Day on May 3rd, but Callaghan seemed resigned to defeat. After the polls closed, in a car with his adviser, Bernard Donoughue, he remarked: 'You know there are times, perhaps once every thirty years, when there is a sea-change in politics.” He was right. The sea-change swept in Margaret Thatcher, the UK’s first woman Prime Minister.

She and her team turned Britain around. She broke the postwar consensus that had acquiesced in Keynesian economics and the postwar socialist measures that Atlee had introduced. She privatized most of the major nationalized industries, and brought the unions within the law to cut industrial unrest. She lowered taxes, raised incentives, and freed the economy from some of the arcane restrictions that had held it back. She allowed state tenants to buy their homes and become homeowners. And abroad she stood up to Soviet bullying and expansionism, a policy that ultimately led to their collapse.

Britain went from being among the poorest performers in Europe to one of the best, from an international laughing stock to a country respected once more. She saved Britain from what many thought must be an inevitable decline, and restored its confidence in itself. It was that crucial vote, 40 years ago, that set these great events in motion.