If only Trump could grasp it - it's consumption that matters in trade, not production

Donald Trump has decided to declare China a currency manipulator, impose yet more taxes on Americans with the temerity to buy what they wish from where they wish. The obvious truth that tariffs are a change in the terms of trade, that therefore the yuan exchange rate should change being missed. So too the point that China hasn’t in fact intervened to cause the yuan to fall but stopped intervening to prop it up. Not doing anything is a pretty strange manner of actively causing something.

But beyond this is the simple foolishness of looking at trade from a production point of view. By chance an obituary offers a little story:

One evening in 1948 Rex Richards, a young Oxford scientist, found himself at High Table talking to a distinguished American guest. His fellow chemist, Linus Pauling, was soon to win not one but two Nobel prizes.

Richards told Pauling of his interest in the new field of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), a process in which nuclei of atoms emit a discernible electromagnetic signal when themselves subjected to a magnetic field. The phenomenon had first been observed by physicists. “I’d quite like to have a go at that,” he said, “but all my physicist friends say I’ll never make it work.”

“The one thing I’ve learnt in my life is never to pay any attention to what the physicists say,” Pauling replied.

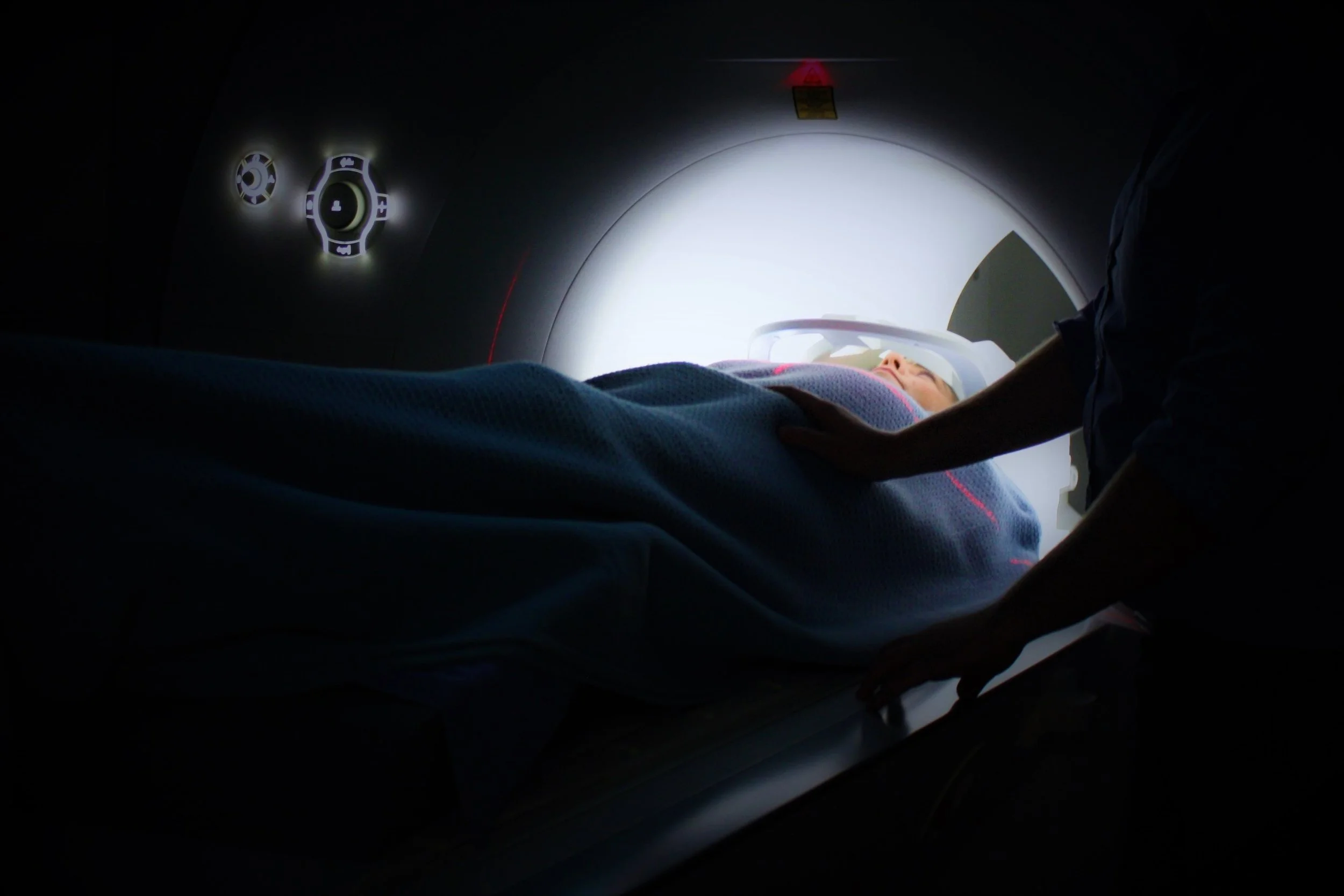

“So,” Richards recalled, “I thought, ‘Well, why not?’ ” The decisive turn his career took that evening was to lead to work that greatly influenced the development of new applications for NMR. Perhaps the most familiar use of NMR is in the form of magnetic resonance imaging: medicine’s MRI scan.

That it was actually a pair of physicists who developed the actual MRI machine is just a little bit of fun here.

The point about trade being. The secret at the heart of one of these machines is a crystal - some 5 or 10kg - of lutetium oxide. Made by the same process, but otherwise in an entirely unalike manner, as we all used to grow copper sulphate crystals in stinks class. It is this which turns the changes in a magnetic field into variations in electrical current - it’s piezo magnetic we believe the phrase is - that can then be used to paint an image on a screen.

Two decades back these crystals were made in a factory in Texas. Pretty much all of them for the world - the plant used some 2 tonnes of lutetium a year, about 90% of global consumption at the time. There wasn’t anyone else using much of the stuff so no other production line.

At which point, what’s the important thing here? That some few jobs were located in Texas? Or that the world got cured by access to MRI machines? Or, more accurately, some subset of the world got diagnosed by them? Access to the machine is, we would submit, rather more important than who has made it. Which is indeed the point about trade. We gain access to what is made is the point of it. At which point trade wars over where things get made become redundant, positively harmful even, don’t they?

How cannabis legalisation can prevent violent crime

Yesterday, the Sun attempted to settle once and for all the debate on cannabis legalisation. Trumpeting a series of warnings that such a move would turn ‘a new generation into hard drug addicts’, the piece swiftly concluded that the UK would become the next Los Angeles, riven by violent crime fuelled (supposedly) by legal cannabis products.

The evidence to support this, however, is rather dubious. Perhaps the most striking misinterpretation stands at the beginning of the piece, where a connection is drawn between the legalisation of cannabis in California and rising gang-related violence. A cursory glance at the FBI’s murder rate statistics shows that the homicide rate in California is indeed rising, and has been since 2010. But so have rates in almost every other state, with Louisianans taking the highest tally of eleven murders per thousand people, a place where cannabis is still illegal. Indeed, the use of only one sample city in the Sun’s report renders the findings more or less void even without resorting to contextualising statistics. In fact, studies of US border states where medical cannabis is available show a major reduction in violent crime, as well as localised reductions in crime rates corresponding to the locations of legal dispensaries.

Inaccuracies raise their head very shortly afterwards with the blanket assertion that cannabis users are thrill seekers. This leads to the apparent conclusion that if the drug were to be made legally available, it would only be a short while before its users resorted to the illegal market again for other stronger substances like cocaine in order to feed their addictions. But the major function of cannabis as a gateway drug is simply through contact with illegal dealers, who are able to offer stronger and more dangerous drugs in an unregulated market. The assertion also ignores the wide range of uses that the product has, not least (as heavily reported by the Sun) as a treatment for epilepsy.

Taxing higher potency cannabis at higher rates—a measure that could only be effective within a legal, regulated market—would allow the state to have some measure of control over the strength of the substance. It is estimated that the UK cannabis black market is worth approximately £2.6 billion, and even a small amount of tax revenue from this could fund measures to counter violent crime, from a greater police presence to counselling and healthcare measures to help the areas most affected by more damaging drugs. A study by Washington State University even connected legalisation with higher crime clearance rates, police resources being freed to tackle the root causes of crime.

The act of decriminalisation alone would claw back huge amounts of money currently spent by the UK government prosecuting cannabis suppliers and users, and allow law enforcers to focus on genuine social issues. Labour MP David Lammy recently expressed concerns that many young people experience their first arrests through cannabis possession, acting as a gateway to violent crime. An early criminal record can also damage future prospects, tying young people into situations where further involvement with crime can be the only option. By contrast, in states like Canada where cannabis is legal and regulated, that early criminalisation can be avoided.

Correlation, of course, is a very different thing to causation, and studies on the matter are resoundingly inconclusive. For every link drawn between cannabis and mental health issues, there is a response emphasising its benefits. If prescribed for the wrong condition it can, like many over-the-counter products, be harmful, but it has also been shown to have positive impacts on many conditions such as depression and PTSD at the forefront of modern medical research. In a similar vein, researchers at the University of British Columbia have theorised that it may have potential in the fight against opioid addiction, providing an effective substitute in order to reduce the harm caused by more dangerous substances.

It is therefore clear to see that far from being a conduit to violent crime, legalising cannabis would help reduce it on several counts. It would also allow for the UK’s world-leading drugs industry to explore its potential in treating mental illness, as well as allowing police to work with affected communities and tackle violent crime at its source. Legalisation and regulation would turn cannabis from a gateway to crime into a crucial tool to prevent it, not only disassociating it from violent crime but turning it into one of our most powerful assets for prosperity and wellbeing. The naysayers should take note.

The decision to bomb Hiroshima

On August 6th, 1945, a US B-29 bomber dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima, a single bomb equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT. Hiroshima was reckoned to be a contributor to Japan's war effort, though civilian and military facilities were intermingled, as they were throughout Japan.

The Manhattan Project that created the bomb was so secret that not even Vice-President Truman knew of its existence. However, within minutes of being sworn in following the death of President Roosevelt in April, Truman was given an urgent briefing about the impending weapon. The decision to use it was his alone, though his advisors supported its use, as did Winston Churchill. Truman had four choices. He could continue with conventional bombing of Japan, bombing that had killed an estimated 330,000 people and wounded a further 473,000 between April 1944 and August 1945. More than 80,000 people had died in a single fire-bombing of Tokyo, a greater number than those killed at Hiroshima. Truman later wrote,

“Despite their heavy losses at Okinawa and the firebombing of Tokyo, the Japanese refused to surrender. The saturation bombing of Japan took much fiercer tolls and wrought far and away more havoc than the atomic bomb."

A second option was an invasion of Japan that would have killed millions, including an estimated 400,000 to 800,000 American dead and many more wounded. Iwo Jima had seen 6,200 US troops killed, and Okinawa had cost the lives of 13,000 US soldiers and sailors. The Japanese had fought fanatically, heedless of casualties, and US casualties at Okinawa had been 35%, with one in three participants killed or wounded. An attack on the mainland would, Truman thought, resemble "Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other." The prospect of the bodies of young Americans lying on its beaches and in its hillside jungles, motivated Truman to bring a decisive end to the war without that option.

There was the possibility of a test in an unpopulated area, maybe on an island, to demonstrate the bomb's power and induce Japan's surrender, but it was thought unlikely to achieve that objective. The US side wondered who on the Japanese side would assess the result, a single scientist, or a committee? And would the nation surrender what it saw as its honour on the word of so small a number? The US only had two bombs, so a test would have used half their nuclear arsenal. Truman's advisory committee told him, “We can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war."

Truman decided on a military use on a populated area, intending it to shock Japan into a surrender. It was not a decision he made lightly. He wrote, “My object is to save as many American lives as possible but I also have a human feeling for the women and children of Japan.” Nonetheless, he recorded that, "When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him as a beast.” When Truman announced the use of an atomic bomb to the world, he warned,

“We are now prepared to obliterate more rapidly and completely every productive enterprise the Japanese have above ground in any city. We shall destroy their docks, their factories and their communications. Let there be no mistake; we shall completely destroy Japan’s power to make war... If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the likes of which has never been seen on this earth.”

It took a second bomb, dropped on Nagasaki on August 9th, to bring about Japan's surrender a week later. A 21-year-old American second lieutenant recalled,

"When news began to circulate that [the invasion of Japan] would not, after all, take place, that we would not be obliged to run up the beaches near Tokyo assault-firing while being mortared and shelled, for all the fake manliness of our facades we cried with relief and joy. We were going to live. We were going to grow up to adulthood after all.”

Truman never regretted his decision. He made it and said, “That’s all there was to it.”

Chuka Umunna fails to understand incentives - par for the course

Quite what Chuka Umunna’s political beliefs are - other than Chuka Umunna - is somewhat difficult to divine. Other than the general belief that everyone needs to be told, hand-held, through what they wish to do. Centrists of no particular belief are often enough statists after all.

So, it comes as no surprise to find that Umunna doesn’t understand incentives.

Most firms that export only to the EU do not have the paperwork they need to carry on their business after a no-deal Brexit, government figures suggest.

Gosh, you mean bureaucracy and box ticking are an important part of trade with the EU? Who would have thought it?

In more detail:

Firms that export and import beyond the EU already have an EORI number, but registration has become a pressing issue for the 245,000 who trade internationally only within the EU. A no-deal Brexit would be particularly difficult for them because, instead of having current rules apply during a transition, they could find their trading opportunities shut down after 31 October without an EORI number.

Chuka Umunna, the former Labour MP who is now the Lib Dem Treasury and business spokesman after defecting to the party, said he had obtained figures from the government showing that just 66,000 of these traders had an EORI number. He said that at the current rate of progress it would take until 2021 for all firms to get the paperwork they need.

“These figures reveal that an overwhelming majority of UK exporters to the EU are unprepared for a no-deal Brexit and will not be in a position to deal with the mountain of red tape and bureaucracy it will burden them with on 31 October,” Umunna said.

“Pursuing a no-deal Brexit is a wholly irresponsible political choice of the new administration for which there is no mandate and which will put businesses and jobs at risk.”

Well, how big a problem is this? As the government itself says:

Apply for an EORI number

It takes 5 to 10 minutes to apply for an EORI number. You may get the number immediately, but it could take up to 3 working days if HMRC needs to make more checks.

That is, the number who don’t have a number on Monday October 28th could be a matter of mild concern. It isn’t today.

And why isn’t it? Because incentives. People tend to do what they need to do in order to carry on doing what they wish to do. There is no direct incentive today for small firms to apply for such a number. Come mid-October that incentive rather starts to appear. Therefore we expect the rate at which numbers are applied for to rise. Incentives matter, d’ye see?

What’s really needed to make Housing First work

8,855 people slept on London’s streets last year alone. This represented an 18% rise over previous years. It is almost inconceivable that now, in the most peaceful and prosperous era in history, in one of the world’s most developed countries, so many people are sleeping on pavement.

This crisis is not for lack of solutions. Housing First, a policy idea first developed in New York by clinical psychologist Sam Tsemberis, has proven immensely successful and entirely rethinks traditional approaches to homelessness. Typically, housing programmes involve offering temporary, often not private, housing only on certain conditions; a person can only gain access to shelter after proving themselves ‘worthy’. These conditions often include proving budgeting skills or addressing mental health problems or addictions. Housing First does the exact opposite. It provides (semi-)permanent accommodation to those in need—prioritising the chronically homeless and those with the most damaging physical and mental illnesses and vulnerabilities—with no strings attached. It is rooted in the belief of housing as a right, not a reward, and an understanding that once a person has their dignity in the form of a safe, stable environment and a place to call their own, they are then much more capable of addressing other barriers to improving their lives, such as addictions and health issues. The end goal is eventually employment and an independent, stable life.

Housing First has proven extremely effective and become policy in places from Finland to Utah, nearly eliminating chronic homelessness, as discussed by the ASI previously here. The UK has followed in Finland’s footsteps and instituted Housing First as part of its ‘Homelessness Reduction Act’, passed on 27 April, 2017 and coming into law in one year later. In a one-year inquiry held on 23 April of this year however, the results were positive, but extremely limited for two reasons.

Firstly, largely because of the limited application of the programme, very few people actually knew how their rights to housing had changed under the Act. The inquiry concluded that only 6% of people approached their local council for housing help directly because of the Act (Q3). Secondly, the inquiry emphasised that “you cannot relieve homelessness unless you have a home to offer somebody or to help them into” (Q2). Where the Act was implemented, there was already a lack of social housing available—putting upward pressure on prices—and few alternatives for even relatively short-term accommodation. Thus, while the UK has taken the first proper steps towards addressing this crisis of basic rights, a much more holistic approach needs investment - something which I see being enacted through the investment in large-scale housing blocks or ‘villages’ of micro-homes. Similar ideas have been enacted across the US, including outside Ithaca, in San Francisco, and in Boston, to significant success.

Invest in the construction of a large number of micro homes or apartments, clustered in ‘villages’ and with spaces to emphasize a sense of community and social involvement, but close to city centers and local resources to prevent a larger sense of social exclusion. Inexpensive architecture options such as pop-up ‘pods’ can help keep costs down. Each tenant is given their own space, complete with necessary amenities, and larger units are available for families. All the principles of Housing First are applied: tenants have contracts, pay up to 30% of their income towards their rent, and are never under threat of eviction. They are granted the dignity of their own safe and stable home, a community of others who have been through what they have, and, most crucially, access to support services including a GP, mental health services, a jobcentre, further tenancy support, and assistance with documentation such as obtaining an NI number, applying for jobs, and other steps towards independence. The housing would be ‘semi-permanent’, having no set end date, but with the explicit understanding that tenants will either move into social housing or the private rented market when able.

By providing people with their most basic need—that of private shelter—we allow people a chance to reenter society as an active participant, not an observer from street level. And by providing people with the support they need, from a relatable community to social services all within accessible range, we provide them the best possible opportunity to do so. Much research has been done on the economics of this, and the costs always outweigh the benefits of increased economic output, a reduced drain on public resources such as NHS services, and fewer people going endlessly through ‘the system’. If the government invested in ‘villages’ such as these in all major cities across the country, they could join the club of societies which have all but eradicated homelessness through a compassionate and realistic approach; if people do not have homes, give them homes. Everything else will follow.

Melissa Owens is a research intern at the Adam Smith Institute.

Friedrich Engels, unlikely Marxist

Friedrich Engels died on August 5th, 1895. He is best known, of course, as the person who collaborated with Karl Marx to develop the theory of Communism. He co-wrote several publications with Marx, including, most famously, "The Communist Manifesto." He himself was born into a wealthy German family, and his father owned large cotton mills in both Germany and Britain. It was from the proceeds of these that he financed his own life, and later financed Karl Marx to work on "Das Kapital." After Marx's death, Engels edited the 2nd and 3rd volumes of it.

His own philosophy was heavily influenced by Wilhelm Hegel, and he was associated with the Young Hegelians while attending lectures at the University of Berlin. Suffused throughout his work was the notion of dialectic, which Engels applied to the material world as "dialectical materialism." The notion that real-world material conditions, such as the division of classes, contained contradictions that could ultimately be resolved only by revolutionary clashes, formed the basis of the Communist revolutionary creed.

Engels wrote essays about how the working classes lived in Manchester, and sent them to Marx for publication. These formed the basis of his influential book, "The Condition of the Working Class in England" (1845), which was not translated into English until 1887. It painted a grim picture of working-class life in Northern England, with poor quality housing, sanitation, food, and conditions of work. Its influence was such that for a century after he wrote it, historians treated the Industrial Revolution as something that had brought squalor to working people. What Engels had not appreciated was that, bad though the conditions he saw were, they had been worse in the rural hovels from which people had moved into the towns and cities. Industrial work was an improvement on the wretched, impoverished, malnourished and short lives they had lived in the country.

It was not until T S Ashton published "The Industrial Revolution" in 1948 that the Engels view was reversed, and people began to see that revolution as one of the greatest advances mankind had ever made. And far from the violent clashes through which history was supposed to achieve its inevitable destiny, people in the English-speaking world began to see more merit in the Darwinian view of gradual evolution than in the Hegelian one of spasmodic clashes.

In Russia, though, the Communist revolutionaries who seized power placed Engels alongside Marx as the intellectual justification for their actions, and many posters showed the three of them in heroic poses, with Lenin as the logical successor to Marx and Engels, and the heir to their tradition. Engels had written that the state's only purpose was to abate class antagonisms, and once social classes based on property had ended, the state would have no further purpose and would wither away. This did not happen, of course, in Russia or any other Communist country. Quite the reverse.

Engels presented the picture of a most unlikely Communist. He liked fox-hunting and poetry, and liked to live the good life, holding famous Sunday parties for the left-wing intellectuals of his day, parties that went on into the small hours of the morning. And he was wealthy enough to indulge his love of music, art and literature. His personal motto was "take it easy." If only he had done more of that, the world would almost certainly have been a better place.

Yes Mr Cohen, we do - and we're right to do so too

Nick Cohen identifies the grand and terrible problem these days:

They believe that markets possess more knowledge than the state.

Well, yes, they and we do believe that. And we’re obviously correct to do so.

What is the price of apples? The market price. What should be the price of apples? Well, assuming we don’t want either dearth or glut, the market price. Given that we are using the market to set the price of apples, not government, we are obviously enough assuming that the market knows more about what the price of apples both is and should be than government does.

The basic logic here is not difficult.

It has also been explored in more formal terms. Hayek pointing out that we don’t in fact have any system that knows as much about everything as that market and economy. Government, any form of planner, simply cannot gather the data and cannot process it into information with either the same speed or efficiency. Markets know more than government, have more knowledge.

This is not to say that markets are always the correct management method for everything. Nor is it to insist that there are never market failures, absences of markets, times when markets need central correction. But the bald and basic statement is indeed true - markets know more than governments.

At the most basic level this is because markets, and their prices, are the agglomeration of the knowledge of everyone. Government is only the knowledge of those in government. 7 billion people do indeed know more than the some 600,000 who are the central civil service in the UK.

This is something that a columnist of long standing should grasp at a gut level. The incoming letters and comments do indeed always prove that the readership at large - and in aggregate - know more than the writer on any and every particular subject. Sure, some to many of them will be wrong but there’s not a single one of us who has ever essayed into print without being corrected by the aggregate knowledge of the readership - they knowing more than we.

This is the very same point. The aggregate knowledge of the people out there is greater than that possessed by any subset of us. Even if that subset is called government.

When Idi Amin expelled 50,000 ‘Asians’ from Uganda

Idi Amin, military dictator of Uganda, was as mad as a hatter. He'd deposed President Obote when he discovered that Uganda's leader was about to arrest him for misappropriating army funds. This was in 1971, but 18 months later his murderous spree was well under way, with thousands killed from ethnic groups he disliked, plus religious leaders and journalists, judges and lawyers, students and intellectuals, among many others. He declared economic war on the tens of thousands of people whose forebears had come from the Indian subcontinent, confiscating their property and businesses.

On August 4th, 1972, Amin ordered the expulsion from the country of some 50,000 of these who held British passports. For some strange reason, in Britain people from the Indian subcontinent are usually called "Asians," which doesn't leave a word to cover those from farther East. These Ugandan "Asians" were entrepreneurial, talented and hard-working people, skilled in business, and they formed the backbone of the economy. However, Idi Amin favoured people from his own ethnic background, and arbitrarily expelled them anyway, giving their property and businesses to his cronies, who promptly ran them into the ground through incompetence and mismanagement.

Amin declared that he had beaten the British Empire, and awarded himself a CBE, "Conqueror of the British Empire." He went on to style himself, "His Excellency, President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin Dada, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular." This was in addition to his claim to be the uncrowned King of Scotland. The "VC" stood for "Victorious Cross," which he had made to imitate the VC medal.

Amin's mad exploits continued. He confessed to cannibalism after human heads were seen in his refrigerator. "I have eaten human meat," he said in 1976. "It is very salty, even more salty than leopard meat." He had 4,000 disabled people, together with several of his own ministers, thrown into the Nile to be dismembered and eaten by crocodiles. Among the 300,000 – 500,000 of his countrymen he had killed was the Anglican bishop of Kampala, his body dumped by the roadside.

The "Asians" he deported in tens of thousands after his decree that August day 47 years ago were lucky that they were merely deported, rather than butchered. I was student at St Andrews at the time, and joined a campaign to persuade the UK government to allow them to settle in Britain. We were successful, in that 30,000 were allowed in, and the remainder were helped to get into Commonwealth countries and the US.

They prospered. The ones who came to the UK set up businesses and ran small shops. Some went from running street stalls to become proprietors of multi-million pound grocery chains. They have been a success story contributing to Britain's economy and society. People of Ugandan ‘Asian’ descent feature among Britain's high achievers and celebrities, including Priti Patel, the new Home Secretary.

As for Idi Amin, it finally took an invasion from Tanzania early in 1979 to bring his bloody reign to an end. He was given exile in Saudi Arabia, where he lived the remainder of his life. Asked by a journalist if he had any regrets about his time as dictator, he replied with a smile, "Only nostalgia."

Electric scooters show why we've got to use markets about climate change, not planning

A currently fashionable insistence is that given the importance of climate change we must abandon market processes and use central planning to reorganise our world. This is of course incorrect as the greater the importance and complexity the more we’ve got to use markets and not planning. Electric scooters being today’s exemplar:

At first glance, the assertion that dockless electric scooters are more environmentally friendly than other modes of transportation seems sound. They don’t emit greenhouse gases. They don’t add to vehicle congestion. “Cruise past traffic and cut back on CO2 emissions – one ride at a time,” touts Bird, one of the most popular scooter companies in the US.

But scooters are not as eco-friendly as they may seem, according to a study published Friday.

Researchers at North Carolina State University found that traveling by scooter produces more greenhouse gas emissions per mile than traveling by bus, bicycle, moped or on foot.

The paper in full is here.

The results of a Monte Carlo analysis show an average value of life cycle global warming impacts of 202 g CO2-eq/passenger-mile, driven by materials and manufacturing (50%), followed by daily collection for charging (43% of impact).

That 202g per passenger-mile is more than the emissions from a flight on a 737-400 of some 185g (115g per passenger km). No, that’s not a fair comparison but the shock value is there.

Now note what happens when we use planning to decide what to do. Our central bureaucrat has to go through these calculations for everything. How much energy does it take to make the steel for a wind turbine? How much coal use in the steel making process cannot be avoided? What’s the scrap to virgin steel mix? What are the maintenance costs out in the North Sea? The bunker fuel consumption of the repair boats? What type of electricity is being used to power the conversion of sand into silicon for solar cells?

These calculations rather being prey to political correctness. That’s how Drax burning wood pellets from 3,000 miles away is counted as carbon neutral. That’s how we got first generation biofuels which are definitely more emitting than burning dead dinosaurs. That’s how Germany has managed to spend at least a trillion euros to go green and thereby increase emissions from lignite usage.

We are here because Hayek was right about the Pretence of Knowledge. It’s all simply too complicated to be able to calculate centrally. We therefore have to use the only calculating engine we’ve got with the necessary processing power - the market economy.

That is, stick our crowbar once into the price system - yea, a carbon tax - and stand back and let the market do the heavy lifting. It’s the only method we’ve got that actually works. Since we’d prefer not to be steaming Flipper in the fumes of the last ice floe then that’s what we’ve got to do.

The more complex and concerning the problem the more we’ve got to use markets.

A lifecycle analysis of a racing yacht crossing the Atlantic as compared to cattle class on an airliner would also be informative, don’t you think?

Surprise! Building more houses lowers the cost of housing

Something we keep being told is that Britain’s house prices are too high. We’re happy with that as either a statement or a critique. To which we say, well, build more houses. The answer that all too often comes back is no, we’ve got to build the right type of houses.

That is, only if we build more affordable housing will housing become more affordable. This having the delight, for the proponents, of confusing two different meanings of affordable. There’s the real one, cheaper, and then there’s the constructed one, special rent limited stuff run by a bureaucracy. For, so goes the argument, building a lot of expensive housing doesn’t make housing more affordable in that real and accurate sense.

This is incorrect:

If a metropolitan area was to alter its system of permits and rules in a way that enabled a substantial expansion in the quantity of housing being built, would this step help to make housing more affordable for those with lower and moderate income levels?

Two answers are hypothetically possible here. One answer points out that new market-driven housing construction will tend to be higher-priced, and therefore that in it offers no near- or middle-term assistance to people struggling with housing affordability. The other answer readily admits that new market-driving housing construction will tend to be higher-priced, but argues that an overall rise in the quantity of housing supplied will affect prices across the entire housing market, not just one part of it.

As it turns out the simplistic explanation wins. Having more housing reduces the price of housing.

This means, of course, that we can solve Britain’s housing problems simply by building more housing, Rent controls, bureaucracies, need make no appearance. In fact, kill off the planning bureaucracy which stops people from building what people would like to live in , where they’d like to live, and we’d solve the problem entirely.

Or, as we repeatedly say, the solution to Britain’s housing problems is to blow up the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 and successors.