They're still not understanding the economics of planning reform

Well, yes, this is rather the point:

In one fell swoop, the entire system that has governed land use in England for more than 70 years has been set ablaze.

Who knew that progressive liberals were such conservatives that something should be kept just because it has existed?

As with Polly Toynbee yesterday though they’re still not grasping the economics of the matter:

Luckily however, in 2018 the government commissioned an independent review to identify the drivers of slow construction rates in England. The so-called Letwin review found that the main bottleneck on housing supply isn’t the planning system, but the “market absorption rate” – the rate at which newly constructed homes can be sold on the local market without materially disturbing the existing market price.

In a system where development is left in the hands of profit-maximising firms, there is a strong incentive to build strategic land banks and drip-feed new homes on to the market at a slow rate. The reason for this is simple: releasing too many homes at once would reduce house prices in the area, which in turn would reduce profits.

By handing over even more power to private developers, the government’s reforms will make this problem even worse.

Let’s imagine that everything up until the last sentence is in fact correct. So, how do we solve this? Producers can only control the total amount of whatever it is that is placed upon the market if there is some monopoly or powerful oligopoly in the system. In a free market you cannot restrict supply in order to maintain price. For if you do the other folks in the market won’t.

So, if a third or a half of the country can now be built upon how can anyone restrict housebuilding so as to maintain prices? They can’t - which is one of the points of the reform itself. And if they try then others won’t thereby defeating the tactic anyway.

Once again we’ve people complaining about their specific worry being solved. Perhaps it would help if those who wished to do economic planning understood some economics?

To complain about the problem you're complaining about being solved

We expect this sort of behaviour from a politician or bureaucracy of course for if a problem is actually solved then there’s no more need for political oversight - interference we mean - nor the existence of the bureaucracy. But we would rather expect one of the country’s senior journalists to be able to do better than this:

Developers are the booming winners in this stagnant decade, sitting on land-banks for a million homes, their executives rewarded in multiple millions.

....

Any remaining local control is dismissed as nimbyism, though records show that 90% of local planning permissions are granted.

It also takes an average of five years to go from empty land to building starting such is the length of that planning process.

Building completions are running at around - we’ve rounded the number just to make the maths easier - 200,000 a year.

It’s reasonable, actually in business terms we say this is the minimum requirement for being sensible, to have in stock whatever it is to cover you until it is possible to get some more. If steel takes 3 months from order to delivery then having 3 months of steel on hand is sensible. If land to build upon takes 5 years to get then a sensible - again, note, this is a minimum requirement - idea to have a five year supply to hand. If building is 200k a year and it takes 5 years to gain more plots then 1 million will be the stock at hand.

if the new planning system shortens that process then the land banks will diminish. Polly Toynbee - for of course it is her - is complaining about the solution to the very problem she is identifying. Not just to be contrary, but because she doesn’t understand the subject under discussion.

We wish we could be surprised at that last sentence.

We've been waiting for this other shoe to drop

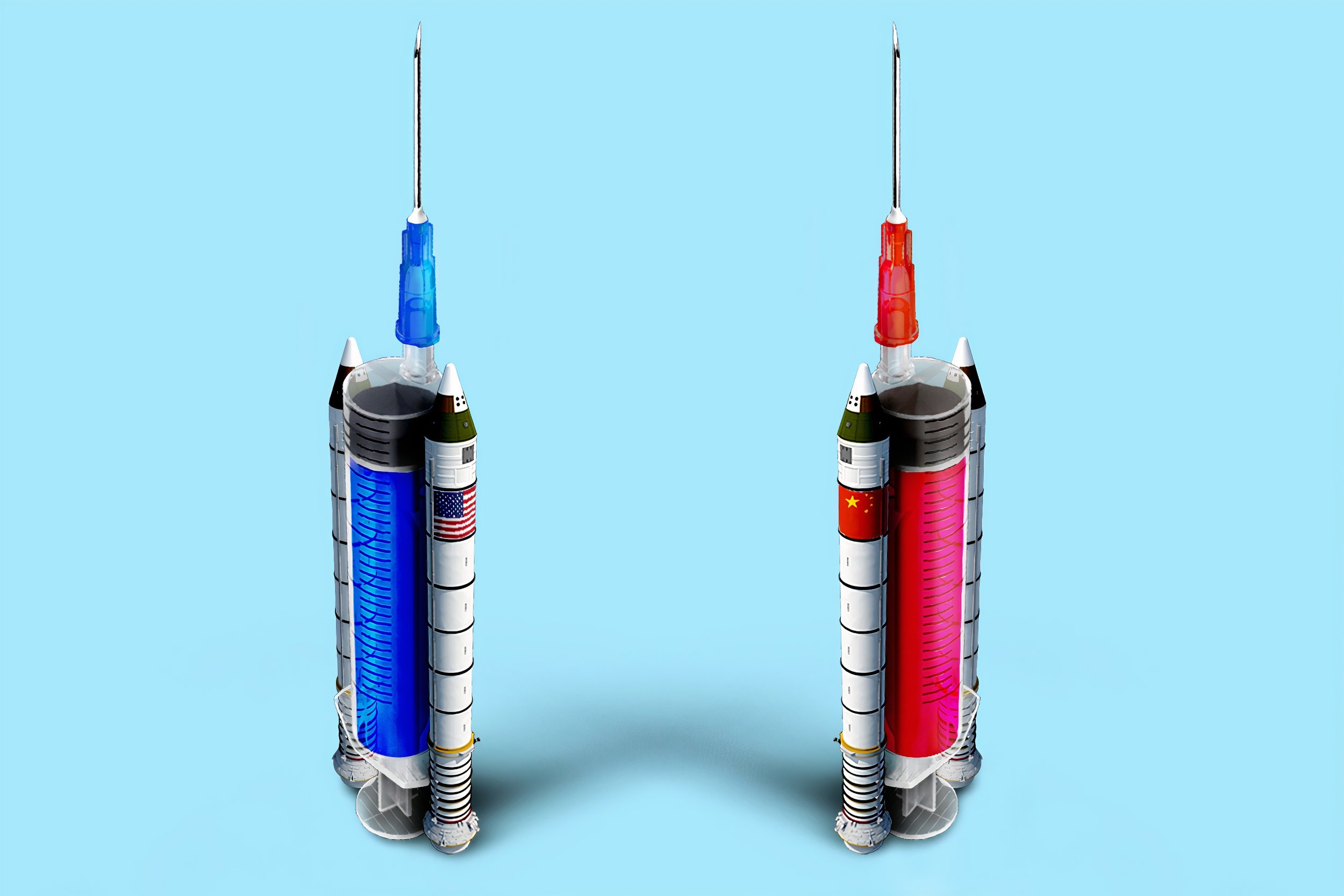

Many of us working in NHS hospitals welcomed the news earlier this week that the government had purchased 90-minute Covid-19 tests. Rapid swab tests, called LamPORE, and 5,000 machines, supplied by DnaNudge, will soon be available in adult care settings and laboratories. If they’re effective, they could allow for rapid, on-the-spot testing. But there’s no publicly available data about the accuracy of these tests or how they perform, raising concerns about why the government has endorsed – and purchased - them.

Think back a couple of months. Then the cry was that tests - any tests - should be used in vast numbers. Government just needs to get out there and buy them. Given this insistence before any particularly valid tests actually existed there was obviously going to be some spraying of money at tests which don’t actually work.

No, we do not say that these specific tests do or don’t. Just that in any such system of payment for development there is going to be payment for developments that don’t pan out.

This also being a larger issue. For pledges are being made to purchase millions of doses of this vaccine, tens of millions of that. None of which have been proven to work as yet. The purchases being across the spectrum of those that might work - which means again there are going to be significant purchases of vaccines that don’t. Or less well than others, certainly government is going to end up buying what is not used. Which will call forth the same wailin’ an’ a cryin’ that these tests are.

However, look on the bright side. It will bring into the public conversation just how expensive drug development is - as opposed to the usual complaints about how high the profits are. For in that usual complaint about capitalist drug development the comparison is made between the amount one company has invested in a drug and the amount of money received from having done so. Which isn’t the correct comparison at all. Rather, it’s all the money that was invested in searching for a drug as against the revenues from the one that succeeded.

Now, with government paying all those costs of all developments we’re going to see this, vividly, how much it really does cost. And yes, large amounts of what is spent is indeed wasted. The thing being that in the old system it’s the capitalists who risk - and waste - their money, in this new world of government drug development it’s us taxpayers. There’s even the possibility that with the costs being made so evident that those who argue fort the nationalisation of drug development will end up having to wind their necks in.

We can hope at least. Drug development is an inherently wasteful and therefore expensive endeavour. It’s probably cheaper to leave it to the capitalists to do then only spend taxpayer's’ money on the winner.

To introduce The Guardian to a little economics

The Guardian has been telling us for a couple of decades now that Britain really must get out of this low wage, low productivity, employment and production system that we have. They might even be right for as Paul Krugman has pointed out productivity isn’t everything but in the long run it’s almost everything.

It is necessary - OK, desirable then - that the paper also know how the economic thigh bone is linked to the economic hip bone. What they desire is happening right now and they’re complaining about it:

Firms cut jobs amid recovery worries

UK service sector companies cut jobs at a sharper pace in July, because they are worried that the Covid-19 recovery will be slow.

So says Duncan Brock, Group Director at the Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply. He warns that there are still serious ‘underlying problems’ in the economy, even though activity grew last month.

From the source, the PMIs:

UK service providers reported a strong increase in business activity during July, with the rate of growth the sharpest recorded for five years. New orders also rebounded during the latest survey period, reflecting an improvement in corporate and household spending. Growth was mainly linked to the phased reopening of business operations across the UK economy. Employment was a weak point in July, with staffing numbers falling at a steep and accelerated pace ...

That is rising productivity. We need to use less labour to produce the same amount. Or less labour to produce more in this case. That’s the very definition of the rising productivity which it is said we should desire and work towards.

There is that necessary connection - rising productivity means fewer jobs in what we do now.

This is entirely vile

Government as mafiosi - nice business you’ve got here, be a shame if anything happened to it:

Donald Trump has demanded that the US government receive a “substantial” cut of the proposed takeover deal between Microsoft and TikTok owner ByteDance.

The president said that he had given Satya Nadella, Microsoft's chief executive, a blessing to buy the controversial video app from its Chinese owner during a conversation on Sunday. However, he insisted that the US Treasury would receive a payment for green-lighting the purchase.

"I did say that 'If you buy it…a very substantial portion of that price is going to have to come into the Treasury of the United States, because we’re making it possible for this deal to happen", Mr Trump told reporters on Monday. "Right now they don’t have any rights unless we give it to them."

This is not misreporting, sadly. The video clip is here.

It was Mancur Olson who told us that government was simply banditry. Better to have stationary bandits who will farm the economy rather than roving ones who will plunder it but it’s all still shades of banditry. While we all know this intellectually it’s still a shock to have it flaunted in our faces quite so obviously.

Pulling some form of comfort from this mess perhaps this will now make more obvious the benefits of investor state dispute systems, ISDS, as is encapsulated in near every trade and investment treaty:

U.S. BITs require that investors and their "covered investments" (that is, investments of a national or company of one BIT party in the territory of the other party) be treated as favorably as the host party treats its own investors and their investments or investors and investments from any third country. The BIT generally affords the better of national treatment or most-favored-nation treatment for the full life-cycle of investment -- from establishment or acquisition, through management, operation, and expansion, to disposition.

....

BITs give investors from each party the right to submit an investment dispute with the government of the other party to international arbitration. There is no requirement to use that country's domestic courts.

We can hope at least.

Ombudsmen yes, regulators no

“Regulator genes” suppress the structural genes that create our growth. Regulators have much the same effect on our economy. In 2017, the National Audit Office counted 90 UK regulators, costing us £4bn. p.a. According to the NAO, “Government’s target [is £10bn.] for the reduction in regulatory costs to business over the period 2015–2020, from an estimated total of around £100 billion each year.” If anyone has seen any sign of that £10bn. do let me know. Add the barriers to entry created by the regulators and UK competitiveness is seriously undermined. The 2019 Nanny State Index showed the UK to be the fourth most regulated country in the EU, after three Baltic countries. Germany, perhaps surprisingly, is the least. Maybe that explains our relative economic performance.

All competitive markets need regulation but they do not need regulators. Consumers are protected by competition, legislation, the media and specialist reviewers such as the Consumers Association. Also by ombudsmen but we return to that later. The UK led the way with Margaret Thatcher’s privatisations starting with British Telecom in 1984. Regulators made sense at the time: a state monopoly could not be expected to transition to a competitive market in a single bound. Regulators were created to drive each private monopoly toward a competitive market, providing consumer safeguards, primarily on pricing. When competition was achieved, regulators were supposed to emulate Cheshire cats. Instead, they created all kinds of things to enforce and, like any organisation spending other people’s money, expand their payrolls.

The dozen largest regulators have, since 2014, formed a trade union, UKRN, that looks for ways to justify their existence. For example, in January 2020 they trumpeted their invention of “performance scorecards”, a supreme example of teaching grandmother to suck eggs. Businesses have known all about such matters for over 20 years and do not need regulators telling them now. What was conspicuously absent from UKRN’s annual report was any performance scorecards for itself or its members. It did, however, note the 25% increase in fees for 2019/20 with a further 15% for the following year. Fat cats yes, Cheshire cats no.

It is a quis custodiet Ipsos custodes problem: no one is ensuring the regulators do what they were supposed to do, namely take their sectors toward fair competition and measurably improve value for consumers meanwhile. Instead they are loading them up with wasteful compliance and bureaucracy. Regulators are supposed to be independent of both government and the sectors they deal with. The Cabinet Office, contrariwise, lists key regulators as being part of government: Ofgem, Ofqual, Ofsted and Ofwat are shown as non-ministerial departments whereas Ofcom and the Financial Reporting Council are “other” bodies. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is not shown at all even though it has a close relationship with HM Treasury.

Instead, the Cabinet Office should remind the regulators of their independence and their original purpose. This means they should be funded by and report at least annually to parliament – presumably the relevant select committees of the House of Commons who might be equally surprised by the news. The precedent is the National Audit Office which reports to the Public Accounts Commission which in practice means the Public Accounts Committee. As the piper tends to call the tune, it is important that funding and reporting follow the same. The boards of all regulators except the wholly trade and professional ones. such as the General Medical Council, are appointed by ministers. That cannot do much for their independence and should cease.

Ombudsmen are similarly supposed to be independent of both government and the sectors they mediate. The above Cabinet Office listing includes seven, two as tribunals, one as an executive non-departmental public body and four as “other” government bodies. According to the Ombudsman Association, there are more than 20. Where a sector has both, financial services for example, their roles overlap. In that case, the Financial Ombudsman reports to the FCA. There are two key differences: regulators are funded by levies on the businesses in the sector and/or the taxpayer whereas ombudsmen are funded by the fees charged to the companies about whom complaints are being made, assuming the complaints have enough prima facie justification to merit investigation. That puts pressure on businesses to resolve their own complaints and does not cost the taxpayer a penny. The other difference is that a competitive market needs an ombudsman whereas it should not need a regulator.

The most expensive, and the most unnecessary, regulator is the FCA, né 2013, which cost £589M in 2018/19. It prides itself on resolving PPI complaints but the Financial Ombudsman dealt with most of those. The body cost another £270M for the year. The FCA had 3.951 staff members, 35% being supervisory, yet most of the major work was contracted out to consultants.

With the benefit of hindsight, it was always unrealistic to expect regulators to plan for, and commit, hara-kiri. A better solution would be to convert all regulators to ombudsmen or merge the former into the latter where both exist, as in finance, for the same sector. In some sectors, being part of an ombudsman scheme is voluntary. Where such a scheme exists, it should be compulsory. To remove gender bias and make them more consumer friendly, maybe they should be retitled “ombuddies”. The new or merged bodies should then report progress toward competitive markets in their sectors and future strategy to the relevant Select Committee which would arrange funding and appoint board members.

We hatched regulators 25 or so years ago; now we should despatch them.

Looks like Bjorn Lomborg was right that 22 years ago

Lomborg’s Skeptical Environmentalist was first published (in Danish) 22 years ago. In which he said - and we paraphrase wildly - that climate change wasn’t that much of a problem. For solar power was going down in cost by some 20% a year. Had been for decades and there was nothing very much that said this wouldn’t continue.

Yes, entirely true, it’s not simple to run an industrial civilisation this way but insolation is such that if we can make it cheap enough then it’s entirely possible. That price drop meaning that we didn’t have to do much more than keep feeding the researchers and wait.

Just a few years ago, low cost natural gas was the main force pushing coal out of the power generation market, and now low cost solar power is sneaking up on low cost natural gas. So far the competition is a trickle, not a flood. However, natural gas stakeholders don’t have much breathing room left, as indicated by the latest perovskite solar cell research.

It appears that he was right. This being what is driving the apoplexy of certain parts of the climate change movement:

Whence the warning about 3 degrees C? The standard argument from the international advocates of climate policy for years was a need to limit anthropogenic warming to 2 degrees C by 2100, officially reduced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2018 to 1.5 degrees C, for the obvious reason that given ongoing and likely trends, the 2 degree C limit is going to be achieved without any climate policies at all.11 Thus has the climate left moved the policy goalposts, a dynamic that has received vastly less critical attention than it deserves.

It’s not necessary to overturn industrial civilisation nor smash capitalism. Some are going to be so disappointed about this. But no worries, no doubt they’ll find a new excuse soon enough.

All of this is entirely independent of whether we should, or should not, worry about climate change itself. The fact is that the standard processes of markets and technological development are dealing with it. As they’ve dealt rather well with other human problems this past few centuries. Meaning that perhaps it’s a system that we don’t want to smash or overturn then?

The lower paid work shorter, not longer, hours

Another one of those Mark Twain things, beliefs that just ain’t so. The argument is that the poor eat horribly junky food because they’ve not got the time to prepare anything else. To busy slaving away at low wages to be able to do anything else, d’ye see?

The problem being that it ain’t true:

The latest campaign against obesity feeds into this history, too. Obesity is a significant health issue and an important factor in Covid-19 deaths. But the reason poor people eat junk food is not because they are ignorant or lack middle-class virtues. It’s because of the circumstances of their lives. Britons work the longest hours in Europe. Many are forced into two or more jobs. Few have the time or the resources to cook like Jamie Oliver.

There are, obviously, those who are both poor and working long hours. Just as there are those swanning around on a high income and doing very little for it. That’s not the way it works out in general though. As the Resolution Foundation reported only this past week:

As we have shown previously, both men and women in lower-paid jobs work fewer hours than those in higher-wage roles

The correlation works the other way. The lower the income the greater the non-working time. Thus the more that can be devoted to that unpaid household labour of cooking a decent meal.

This being more than just a gotcha on an Observer columnist - that’s far too easy a sport. It is actually an important point. Assume that the diet of the poor is indeed a problem. If this is so it is necessary to work out why it is so that something can be done about it. Identifying the wrong cause - a poverty of time to ally with the agreed paucity of income - will mean the crafting of an incorrect plan for dealing with the problem.

As Twain pointed out it’s the things you believe are so that ain’t which are dangerous.

The more we think things must change the more this is a good idea

A suggestion to revive an old policy:

The EAS was launched in 1981. At the time unemployment was hurtling towards three million, and a shocking 30pc of young people had no jobs. The Specials’ Ghost Town was a great song but it also topped the charts that summer because it reflected the bleak prospects most of its audience faced.

The EAS paid anyone who signed up £40 a week, about £160 in today’s money, for a year. They had to be unemployed, and they needed £1,000 in savings or loans. But that was about it. True, you had to submit a business plan, but didn’t need to get your idea approved. There were no committees monitoring your performance. There was nothing to repay, and the support wasn’t scaled back if the business made money. You could just go off and try something out, with some free money to help you along the way.

There is Richard Layard’s great point to consider:

If you pay people to be inactive, there will be more inactivity. So you should pay them instead for being active – for either working or training to improve their employability.

If unemployment is going to be high you might indeed usefully pay people to go and do something rather than the unemployment restriction of you must do nothing in order to gain your dole.

As to the what is being usefully done it’s to explore the universe of things that can possibly be done and see how they match up with what people want to have done. The last time around, that EAS, led to the establishment of Viz. Who knew that what the country really needed was a scabrously foul-mouthed comic? But it did.

The truly important part of the scheme being that no one did pick between ideas before they were funded. It was a true exploration of that envelope of possibilities, not solely of the much smaller set of those approved of - or even understood - by the bureaucracy.

One more point to make. The worse we think the situation is then the more this makes sense. Say that you are insistent that coronavirus changes everything - as the opinion pages of many newspapers are indeed insisting. Or that inequality does, or resource exhaustion, or climate change or whatever is leading to that same conclusion, all must change. So, all must change then. And if all must change then we need to explore all of the universe of possibilities available to us before the selection of those that do take over.

This being exactly the thing that entrepreneurs within a market economy do better than any other system.

If we’ve got to subsidise those unemployed we might as well get them doing something useful for the society as a whole. The more the insistence that change must happen then the more insistent we should be that the subsidy is to explore the changes available.

The worse you think the situation is therefore the more you should be supporting the idea of paying people a couple of hundred pounds a week to go off and have a go. Undirected by the bureaucracy, of course.

What drivel is this?

Everyone loves to hate on the tech giants these days. The unthinking establishment view is that they’re ripping us all off. Thus we have Oliver Kamm, the epitome of that unthinking and establishment view telling us that:

They do not work in consumers’ interests. They give capitalism a bad name.

Let us take just the one example, that of Facebook. Which, through various services like Messenger, WhatsApp and so on allows people to make voice and often enough video calls at no direct cost. Lots of people use these services.

Now perhaps it might be simply our advanced maturity in years but we do actually recall when long distance phone calls were something thought seriously about. They were expensive. International calls doubly so, one did not call up another country simply for a chat. We are also aware that it was only a couple of decades back that it was physically impossible to call much of the world as they simply didn’t have the lines, phones nor connectivity for us to do so.

Now some two to two and a half billion people gain some to all of their telecoms needs, through Facebook, for free.

OK, yes, there are those phone calls which it is not in the caller’s interest to make, often involving late nights and substantial beer, but as a general rule something that used to be too expensive to do casually, that often wasn’t even physically possible, is now to cheap to meter and offered to the consumer for free this is in said consumers’ interests.

It is simply drivel to even wave around the idea that the tech giants are not operating in consumers’ interests. What the heck would be doing that, only if the free telecoms came with a back rub?

We do agree that the world is, as yet, imperfect, even that sometimes government action can and should be taken to getting it closer to the desired state. But we do have to at least start from a valid analysis of the current reality. Something not greatly in evidence in this case of the tech giants,