Learning from the free press why we should free commerce

On Saturday, many of you were left without a newspaper because of a small group of smelly hippies clogging up the roads outside of the country’s printworks. They have decided that the media is full of lies and that you must have ‘free speech’ given to you by their beneficence in the form of you not getting your crossword puzzles.

No, I don’t follow their logic either.

Fortunately, neither did anyone else sensible. Beyond a single deleted tweet by Labour MP Dawn Butler in favour of the group’s actions, and Diane Abbott’s botched comparison between them and the Suffragettes, there was widespread condemnation by politicians across the spectrum for a group who wanted to censor newspapers that they dislike.

Of course, if you actually wanted the news on Saturday, while the papers were full of good stuff, in this modern age it was far more likely that you jumped onto BBC News’ website or one of the papers’ own, or switched on the radio, or went on Twitter, or an app. As my boss Eamonn Butler explained, this was an attack as much on the press as it was on the customer of the physical newspaper.

A number of observations sprang to my mind too.

Firstly, Extinction Rebellion are a right noisy nuisance of the worst sorts of ninnies that most people try to spend their lives avoiding. The biggest threat to their aims is how lame they are. Protests of uncoordinated dances, rhythmic drumming, pants that should have been left in goa when they finished their gap decade. It’s all just, well a bit naff. It turns normal people off the topic of climate change and it hardens attitudes against their proposed measures. As the ex Liberal Democrats leader Tim Farron posted: “Feeling righteous and doing good are not always the same thing.”

Secondly, if they actually cared about the environment they might take care to look at some of the amazing advances being made by those getting stuck into inventions and enterprise. From lab grown meat, indoor fish farms, vertical ocean farming, and how urban density and reduced sprawl can reduce a city's environmental impact, to carbon taxes and road pricing. Free markets and neoliberal policies that build on property rights and monetary incentives are the best hope we have of ensuring our planet is one we are all able to live on and one on which we all do want to live — something my colleague Matthew Lesh recently wrote about in his chapter for Green Market Revolution. If you, or any young relatives you have, are concerned about environmental matters, I’d urge a read of that book.

A third observation came to mind that was somewhat left of field. The newspaper is a little wonder. It arrives at addresses across the country 364 days a year bringing news (Christmas is off, even for Scrooge’s staff), fact, opinion from across the globe condensed into a readable and digestible form and plops onto the doormat simply and easily. It is one of the original right-to-your-door deliveries. The word of man, for you to read and argue over and build new ideas and do it all over again the next day.

Just like Amazon, straight to your doorstep, usually using a local newsagent or network to deliver it to you. And yet, I don’t recall any politician saying that your perusal of a national broadsheet undermined the high street pamphlet printer, or that there should be a delivery tax because you didn’t go and pick it up yourself.

Nor do we condemn papers for taking customers out of high street shops when they deliver direct, preferring to use low cost out-of-town printworks and then lorries and vans and bypasses.

Nor do we slam them for using modern efficient methods of production. They’re not condemned for moving from quill to printing press, or even for using adobe indesign over physical type-setting. The days of the ‘Stop press!’ command are over and online headlines can be changed at the quite literal touch of a button.

And, while there were worries about radio, and then tv, and then websites, podcasts, social media, and apps challenging the traditional print media and its product — there has never been a good justification.

Finally, even though they’re one of the chief beneficiaries of generalised education and literacy we don’t demand they and other publishers pay a targeted ‘education tax’ to get them to pay for the spillover benefit that they receive.

Instead we reap the benefit of a free press unencumbered by restrictions or taxes or coercion. What a wonder it might be if we took the same attitude to commerce of all types.

Really rather missing the point

A survey in India showing that many workers suffered complete loss of income during the covid related lockdown.

Examining the impact of lockdown imposed in late March on more than 8,500 urban workers aged 18 to 40 ofIndia’s 1.3 billion population, it reminds us that under half of those surveyed were salaried employees.

A staggering 52% of urban workers went without work or pay during lockdown, while less than a quarter had access to government or employer financial assistance.

Indeed so and as the paper itself says but doesn’t emphasise, the reason is that most Indian workers are not part of the formal economy. Of course, more in urban areas are than up country, but even so, most are not. At which point a certain amount of missing that point.

For they call for new national policies and government to be involved and…..but why are these people not in the formal economy in the first place? Because the costs of employing them formally are more than the gain from the employment of their labour. The bureaucracy, the taxation, the licences required, the risks to be taken - it being near impossible to fire a formal worker, or even close down a loss making operation or company - plus the wages mean both that few are willing to hire formally and also few get hired formally.

Adding to those costs by introducing another right or tax is not going to aid matters.

As Torsten Bell says, we should note what is happening elsewhere as well as gaze at our own coronavirus scarred navels. We might learn something even - like, perhaps our own explosion of gig workers, those without those employment rights, is a function of the cost of formally employing people? A problem that might be solved by lowering said formal employment costs?

To argue with a Guardian headline

This is of course an isometric exercise, lots of effort to get nowhere. But when such an excessively silly claim is made needs must:

Sunak's reforms are long overdue – income shouldn't be taxed more than wealth

Carsten Jung

Yes, yes it should Carsten. Currently the top rate of income tax in the UK is 45%. We think that’s a bit high. We also think that taxing wealth at 45% would be insane - and so do you. Having disposed of what is being said let us now turn to what is meant.

Which is that income from wealth should be taxed at the same rate as income from labour. This is also incorrect.

A slight detour, in that there is much confusion - some deliberately planted - in this field. We must look at the total tax rate upon a flow of income. Not just whatever portion is charged to a specific person in the flow. So, the taxation of dividends, for example, must include both the income tax charged to the recipient and also the corporation tax charged at the level of the company. We should also adjust with capital gains and so on, for inflation over the period of the gain. Once we do that the gap between those capital and labour income taxation rates narrows. In fact pretty much disappears for dividends, never was there for interest and significantly narrows for capital gains.

The actual science of the subject is over in optimal taxation theory. Mirrlees being a part of it, his Review another. The really big result though being Atkinson and Stiglitz which says that the optimal taxation rate for capital income might well be zero. Most of the more modern scholarship on the point, since 1976, is a bit of smoke blowing attempting to obscure this inconvenient result.

It is certainly economically efficient that the taxation of incomes derived from capital should be lower than those from labour. Dependent upon the definition of fairness being used it can also be argued that it is fair.

Standard economics states that capital incomes definitely should be taxed less than labour incomes. Not that we expect The Guardian to accept that but all those seriously discussing the shape of the tax system should grasp the point, no?

The grand plan from Mr. Varoufakis

Yanis Varoufakis has taken the time out from his busy schedule to produce a plan for the management of the world. It suffers from the occasional problem we are sad to have to say:

But to be crisis-proof, there is one market that market socialism cannot afford to feature: the labour market. Why? Because, once labour time has a rental price, the market mechanism inexorably pushes it down while commodifying every aspect of work (and, in the age of Facebook, our leisure too).

This is not true. It is not even remotely true. Here is the time series (OK, a time series) of real wages in England. The acceleration of wages starts around when capitalist labour markets, unconstrained by the Corn Laws, really start to operate, subsequent to the 1840s. After that well known Engels Pause. Thus the theory behind this new form of socialism fails to have even that nodding acquaintance with reality so necessary for success in the real world.

The pencil sketch on offer of the system as a whole is:

People receive two types of income: the dividends credited into their central bank account and earnings from working in a corpo-syndicalist company. Neither are taxed, as there are no income or sales taxes. Instead, two types of taxes fund the government: a 5% tax on the raw revenues of the corpo-syndicalist firms; and proceeds from leasing land (which belongs in its entirety to the community) for private, time-limited, use.

Essentially the Social Credit of Major Douglas plus the land value taxation of Henry George. We like half of that - and it’s not the Maj. Douglas bit - but it’s difficult to say that the combination is really anything new or radical.

There is also this crippling problem:

But it is the granting of a single non-tradeable share to each employee-partner that holds the key to this economy. By granting employee-partners the right to vote in the corporation’s general assemblies, an idea proposed by the early anarcho-syndicalists, the distinction between wages and profits is terminated and democracy, at last, enters the workplace.

The identifying feature of capitalism is that it is possible to gather capital from outside the labour force of the organisation. The same statement from the other direction, it is possible to invest in adventures that one does not work in. In this system this is not possible. Therefore outside capital is not available to an enterprise. It thus becomes impossible to have any large scale economic organisations - or at least to start any. Well, unless government is going to be doing all the capital allocation and the 20th century tried that idea to destruction.

Sure, there will be those who enjoy this idea. But note what it actually means. The 5,000 or so workers in a modern steel plant will not have the several billions necessary to build a modern steel plant. Therefore we will not have modern steel plants. Nor any of the things that come with such big ticket capital needs. A chip fab these days costs upwards of $6 or $7 billion. It isn’t possible to replace one with some hundreds of smaller scale operations that could be financed by their future workforces.

And of course the inability to tap into outside capital makes starting anything new pretty much impossible.

There is actually a reason why no one has - OK, we’ll admit, as yet - successfully sketched out a workable alternative to roughly capitalist roughly free marketry. Yes, there are flavours within that spectrum, from Hong Kong’s laissez faire to Sweden’s social democracy. But the reason that designs outside that spectrum don’t work is because the two - together, both capitalism and also markets - solve the basic economic problems we face. How to make the people richer through the efficient allocation of scarce resources.

Nowhere has got rich without that capitalism and markets, those who did not get rich but recently adopted the twin system are getting rich and those places which have abandoned them have become poorer again.

Which does lead to an important question - why mess with what works?

The glorious 1000% rise in the number of food banks

This calls for a celebration we think. It’s also a useful example of what happens when we have both technological development and also a rise in the general wealth of the society - we get to do new things, solve old problems:

As the economists Mark Blyth and Eric Lonergan observe, from 1980 to 2017 the UK’s GDP rose 100%. Over the same period the number of food banks in the UK leapt 1,000%.

The rise was rather more compressed than that, the Trussell Trust itself points out that food banks pretty much didn’t exist in the UK when they started in 2000. The technology - a manner of organisation is indeed a technology - hadn’t been imported from the United States at that point. Then it was. Much hunger has been eliminated as a result of the adoption of that technology, we regard this as a good thing.

It is also true that a richer society is able to divert more to solving such problems than a poorer one and as we can see that is exactly what has been happening.

We are, of course, supposed to think the other way around, that’s the point of the statistic being presented to us. That society has become worse therefore the need for such food banks. Reality works the other way around. State inefficiency in distributing welfare did not start in 2000 - we ourselves have direct experience of that not being true. Nor were those 20th century days free of pockets of hunger. What changed was both the wealth to do something about it and also the technology to do so efficiently. At which point we say Huzzah! For the pangs of poverty are being alleviated better than they were before and isn’t that a good thing?

That claim that the increase in food banks is a bad thing is, when thought about properly, an absurdity. For it is to say that solving a problem is proof of the problem getting worse. Instead of what has actually been happening, the world becoming a better place as a problem is solved. We’re all in favour of food banks, who wouldn’t be happy at fewer people being hungry?

Adult Social Care: Broken Promises

The other day I asked a well-informed Tory peer when we should expect the long-delayed adult social care Green Paper. “Not in my lifetime” came the response. Recent history begins with the 2011 Dilnot Report which was accepted by the coalition government, welcomed by the Labour party and then rightly over-ruled by HM Treasury as being impractical and too expensive. It was, or should have been, a start.

There was much talk of achieving cross-party consensus, but no action, and it was left to Select Committees to fill the gap. The government response to the Health Committee’s 2012/3 report included “The Government will work with stakeholders and the Opposition to consider the various options for what shape a reformed system could take, based on the principles of the [Dilnot] Commission’s model, in more detail before coming to a final view on reforming the system in the next Spending Review.”

The Health and Social Care and Housing, Communities and Local Government Committees published a joint report in June 2018. Their four main principles were:

Ensuring fairness on the ‘who and how’ we pay for social care, including between the generations

Aspiring over time towards universal access to personal care free at the point of delivery

Risk pooling—protecting people from catastrophic costs, and protecting a greater portion of their savings and assets

‘Earmarking’ of contributions to maintain public support”

The Care Minister could not comment as the Green Paper would follow “this autumn”. Her letter was undated, so the autumn to which she referred is still unclear.

A Commons Library briefing note has a timeline of Green Paper postponements up to September 2019. Amongst them are: “January 2019 – Mr Hancock told the House that he ‘intends’ for a social care Green Paper to be published ‘by April’”. When there was no sign of it by the end of April, he “attributed the ongoing delays to a lack of cross-party consensus”. As the Opposition pointed out, there was nothing to be consensual about.

In a speech to the Local Government Association (LGA) in July 2019, Matt Hancock said “Infamously, during the 2017 election campaign. But more recently too – when my colleague Damian Green recently proposed a scheme very similar to a plan supported by not one but 2 cross-party Commons select committees, by 10:42am on the day of the launch, the Shadow Chancellor had condemned it as a ‘tax on getting old’. It’s not the first time narrow partisan politics has got in the way of a solution, but let us hope it’s the last.”

It was naïve of the Tories to assume that Select Committee agreement equalled cross-party consensus and still more to rush out such a controversial plan mid-campaign. Labour also called it a “dementia tax” and it nearly cost Mrs May the 2017 election.

Significantly, when the senior civil servant, Jon Rouse, Director General for adult social care, left in 2016, he was not replaced until this year. The 2012 Health Act was supposed to leave NHS matters to NHS England, with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) attending more to the last part of its title. That has not happened: the vast majority of DHSC announcements have referred not to social care, still less working age social care, but to the NHS – ignoring Sir Simon Stevens, its CEO of NHS England, who is more than capable in speaking for his own organisation. In July he tried to balance the picture by demanding an adult social care Green Paper within the year.

Hancock’s LGA speech referenced above gave an indication of his Green Paper thinking, in brief: “integrated care systems (ICS), bringing together the NHS with local authorities”, “health and wellbeing boards”, “specialist training”, “better leadership”, “increasing the Carers Innovations Fund”, “more control for care users” and “tech”.

Some of this is sensible enough, some just adds bureaucracy and some are junk-filled platitudes. Care users cannot get what they want if it is not available. We were 122,000 carers short the last time I looked. We know the DHSC’s record with new IT, test and trace apps being the most recent example, so do not hold your breath for “Social prescribing apps are being integrated with GP systems to give people greater access to social activities in their communities that can help improve physical and mental health.” The idea one needs an app to get the GP to prescribe riding a bicycle is ludicrous.

What these seven components of the Hancock vision fail to include are the three essentials: more money for carers, greater professional status akin to nurses to build pride in the profession, and less bureaucracy giving them more time and freedom to do what they believe to be best.

Nor is there any discussion of finance. HM Treasury has probably been blocking any social care Green Paper and are likely to continue to do so. That ignores individuals’ increasing willingness to contribute towards their own old age costs. French and German insurance companies offer cover and most of those who can afford it take it up. There’s only a 40 percent chance one will have to spend one’s final months in a care home. The government has made no effort to encourage British insurers to follow suit.

The broken promises did not stop there. During the last election Boris Johnson claimed a Green Paper consensus would be developed within 100 days of being elected. At nearly the end of that, nothing had happened and Hancock wrote to all peers and MPs saying, in effect, that as he had no clue, please would they send in any ideas about reforming social care. And although care for the elderly gets all the headlines, about half of adult social care costs are for those of working age.

The current excuses for the broken promises, namely Covid and the upcoming financial crisis, do not hold water. Thousands of DHSC civil servants have been sitting at home on full pay with little to do but write the Green Paper. We need an adult social care strategy that will do the job, as the NHS has, for decades. This demands some degree of political party consensus. Any party that fails to respond constructively to a sensible Green Paper will pay the price at the polls. And the strategy does not have to begin tomorrow; it should start as soon as we can afford it. The failure to deliver rests squarely with this government.

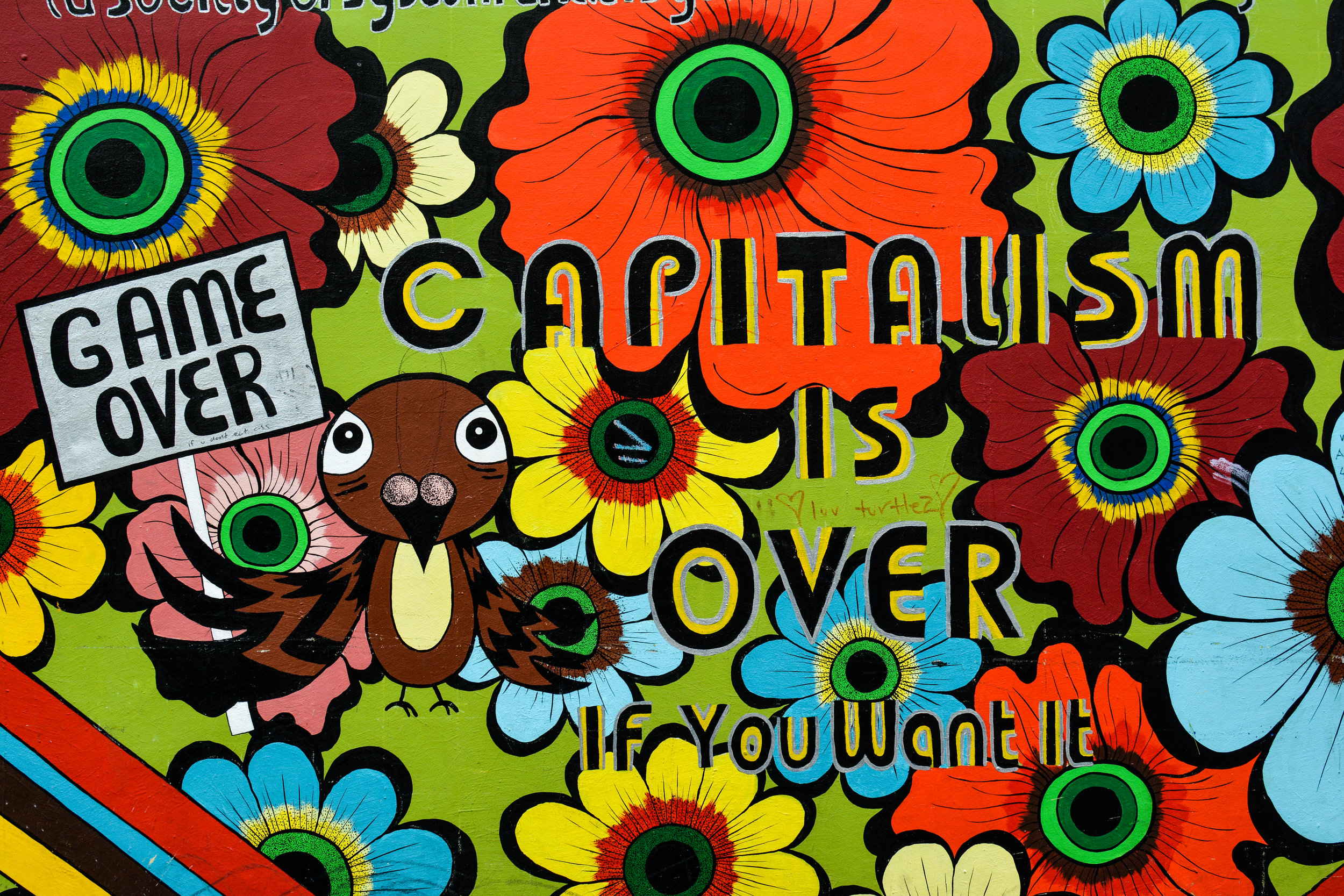

It's amazing how everything requires the overthrow of market capitalism

We have Julian Baggini, a philosopher - supposedly someone who therefore knows how to think - telling us that the cure to obesity is the overthrow of market capitalism:

If the government wants to help people to eat better, its main priority should be ending what is often called food poverty – more accurately described as poverty, full stop. The poorer you are, the more likely you are to be overweight, almost certainly because of the way poverty limits your food choices. If people cannot afford good food, or the fuel to cook from scratch at home, telling them to eat less and better is pointless.

Of course we should all try to take responsibility for our own health. But we can be responsible only for what we have the power to do. That is limited not just by basic biology, but by what is on our shop shelves and in our wallets. Tackling those problems requires controls on business and greater redistribution of wealth. The government rejects both on ideologic grounds, and instead promotes dieting and personal responsibility, preferring flawed common sense to the evidence.

Good food being defined as food not processed by the Big Bad Companies which must be controlled etc.

One useful filter for an argument - it is only a filter, not a proof against - is that if the course of action is what would be recommended anyway then we can discount this particular justification for it. The Guardian’s opinion pages are going to recommend less income inequality, more control of business, because the Sun rises in the East so this particular, obesity, justification doesn’t carry that much weight.

We can also discount it because it doesn’t make sense. The claim is that eating processed supermarket food is cheaper than home cooked. This simply is not true in any manner. The saving is in time, not money and while time is indeed money confusing the two at this point leads to the wrong conclusion. For if it is time to home prepare food that is lacking then it is the dual earner family that is to blame, not the food factories.

But look deep into the heart of the argument here. The base human problem since Ur of the Chaldees has been how does everyone get enough to eat so that they don’t starve to death? We have, in this past century in this country, rather later in many other places, finally solved this problem through industrial, free market, capitalism. The claim is now that because the poor can eat we must therefore overthrow the system that allows them to do so. Truly, any reason at all to overthrow the system, even the successes are to be used as evidence against.

As to the actual claim itself, food poverty, the average household weekly food bill is £61.90. If you prefer to do it over the income range, for the bottom decile it is 53 % of the top decile’s or about 65% of that average. We assert that it is entirely possible to eat healthily on that sum. We’ll even prove it if anyone is looking for a TV show - “ASI Does Benefits Street” has a ring to it. No takers? Then that initial claim isn’t something that people really believe, is it?

People do indeed question what doesn't seem to work Polly

Polly Toynbee is outraged - outraged - that people are questioning the Wonder of the World that is the National Health Service.

The clapping has died away, paper rainbows in windows curl at the edges, and the NHS is under siege. “Support for the NHS may soon start to crumble,” reports the Centre for Health Communication.

“Start to? It has,” says one seasoned hospital chief executive I check with regularly. Emails thump into his inbox daily from angry patients waiting for diagnostics and treatments: “They’re coming direct to me now.” As 50,500 people across England have been waiting over a year, he says, “my waiting times are horrible. Pre-Covid I had just four people waiting for a year, but now it’s over 1,200 – and we’re absolutely not the worst.”

Well, yes, quite, if the thing that swallows 10% of the entire nation in order to provide health care isn’t providing health care then there will be some questions asked. And rightly so we would think.

We can even provide some guidance as to what those questions should be. You know, things like whether a Stalinist bureaucracy is quite the way to be doing things. Even, did the NHS England, a slightly more outsourced and marketised service, perform better or worse than the less so NHS Wales and NHS Scotland?

In fact, we should be asking the one grand question - is the NHS the right way to be gaining health care? Given that the complaint is that it’s not delivering it at present that seems to be the important one.

Sure, let's have a shorter working week

We’ve no problem with everyone gaining more leisure time. It is what has been happening these past couple of centuries as the increased wealth and income of free market capitalism leads to people choosing exactly that. True, the choice has oft been to reduce household labour more than market but then that’s the choice people are making so why shouldn’t we run with that - the people get what the people choose sounds like a decent enough outcome to us.

We would also note that absolutely nothing in this field is going to make sense without considering the basic human economic unit, the household - it is not the individual.

That doesn’t mean we support every such proposal of course:

A four-day week in the public sector would create up to half a million new jobs and help limit the rise in unemployment expected over the coming months, according to research by the progressive thinktank Autonomy.

The report points to the German Kurzarbeit scheme as an example to follow and then misses the two important points of that very scheme.

Firstly, Autonomy says that those working fewer hours should lose none of their income and that’s not how the Germans do it at all. They, correctly, note that if the workers are getting these shorter hours for free - at no loss of income - they there will be a certain excess of demand. Such schemes are costly and it’s only by distributing that cost around all involved, employers, taxpayers and workers, that we’ll gain the optimal amount.

The other mistake, and it’s a biggie, is where Autonomy says this should apply. From the German justification:

And companies retain firm-specific human capital, while avoiding the costly process of separation, re-hiring, and training.

It works if highly skilled labour, that difficult to find and hire or train once done so, is retained. So, the lads at Autonomy suggest that:

Aside from potential lay-offs, hospitality, retail and the arts are already associated with low productivity, stagnant wages and insecurity, with any further damage to these sectors likely exacerbating these problems.

The scheme should be applied to sectors where none of those hold true. Insecurity is, of course, the other way of describing how easy it is to hire and fire in the sector. Further, there’s the blinding silliness of looking to subsidise low productivity jobs. It is their destruction and replacement with higher productivity ones that drives the increase in the wealth of the nation. Higher productivity and wealth being what allows us all to take some portion of that as greater leisure, as we have been these past couple of centuries.

Sure, subsidising jobs for luvvies gets the luvvies on side but we need a better justification for spending £9 billion than that.

This plan is just another example of people not understanding the very issue they hope to discuss. Tsk, must do better.

A Mars a day helps the economy work

Gary Becker pointed out that irrational, or taste, discrimination is costly to the person doing the discriminating. There are entirely rational forms of discrimination, of course - making babies works rather better with the appropriate mixture of gametes and gonads for example. But that taste kind, to refuse to hire blacks, or women, or the short or tall - as opposed to not hiring one armed paper hangers - rebounds upon the person making the choice.

Talent is scarce and by refusing to hire what there is this lowers the price of talent to all competitors. That redounds upon the discriminator through competition from that talent now elsewhere.

The usual response to Becker’s point is yes, true, but no one actually works that way. Thus we need laws against that discrimination. Except:

Despite its secrecy, Mars is remembered fondly by those who worked there. Leighton, who helped transform Asda’s fortunes before selling it to Walmart in 1999, said: “They gave me the greatest quote of all time, which was, ‘Your job, Allan, is to get more brains than anybody else, and remember that 50% of the brains in the world are female and brains have no colour. It will take people a long time to work that out.’ They told me that 35 years ago — and they were right.”

Actual evidence that people have indeed been noting that point about talent and discrimination for more than a generation*.

It also doesn’t take much. Just a few following the self-interested precept of no taste discrimination upsets the stable structure and brings about that end of it. Which is why the Jim Crow laws were even institute in the first place. That battle for talent, that competition, would undermine the discrimination therefore laws were imposed to insist upon it.

If we need, as history showed we did, laws to maintain the discrimination and, in a free market the discrimination gets undermined by simple good sense and greed, then why do we need laws against the discrimination?

*In Sir Pterry’s phrasing, just more than a grandfather