An error of logic on climate change

Well, this is good news:

Reaching net zero carbon emissions in the UK is likely to be much easier and cheaper than previously thought, and can be designed in such a way as to quickly improve the lives of millions of people, a senior adviser to the government has said.

Chris Stark, the chief executive of the Committee on Climate Change, the UK’s independent statutory adviser, said costs had come down rapidly in recent years, and past estimates that moving to a low-carbon economy would cut trillions from GDP were wrong.

“Overall, the cost is surprisingly low – it’s cheaper than even we thought last year when we made our assessments. Net zero is relatively low-cost across the economy,” he said.

Leave aside whether it needs to be done at all. If it does then it being cheaper is good, if it doesn’t but they’re going to do it anyway then it being cheaper is good.

The error of logic is here:

“But that rests on action now. You can’t sit on your hands and imagine it’s just going to get cheaper by magic.”

Renewable energy prices have plunged in the last decade, putting solar and wind at lower cost than fossil fuels in many countries, spurring a global boom in clean power.

So, how has this been done then? By people out there making cheaper windmills and cheaper solar panels. By, that is, free market competition among capitalist, profit hungry, producers. Sure, we can say that some kickstarting was necessary. We tend to think that not much was and that this has all been done in a grossly expensive manner but, you know, opinions and all that.

But consider the situation now. The claim, at least, is that these solar and wind things are cheaper than fossil. So, the competition remains among those capitalist, profit hungry, producers to continue to gain market share. Which they will do by continuing the technological development of those already profitable - they must be, otherwise the claim of their being cheaper cannot be true - products of theirs.

That is, even if it is true that something had to be done that something has been done. Our correct response now is exactly to sit on our hands because it is all going to get ever cheaper. The magic being that combination of the capitalist lust for profits combined with the competition of free markets.

Or, as we might put it, exactly the success claimed by those who call for intervention means the end of the need for the intervention. We’ve already solved the problem, we’re done.

Oh, and as to our claim that this has all been done too expensively. Back in the 1990s people like Bjorn Lomborg were pointing out that solar was getting cheaper at 20% a year and that that, by the 2020s, would mean it was cheaper than fossil fuels and so the problem would be solved. Here we are, 2020s, the claim is that solar is cheaper and the problem is well solved. We’ve spent a fortune getting here and arguably we needed to spend nothing at all to do so. Because that technological trend, the 20% pa reduction in the price of solar, hasn’t changed, not so as we’ve been shown at least, as a result of all that spending.

Why not stop making that mistake and just leave it to that capitalist free marketry that actually has been solving the problem so far?

Pfizer's vaccine is something of a blow for the Mariana Mazzucato thesis

Mariana Mazzucato tells us that technological advance comes from wise investments by the omnisicient and beneficial state. Her proof is that some technological advances have come from investments by the state. One answer to this is that given the state’s appropriation of 30 to 40% of everything we’d rather expect to gain the occasional snippet of a public good in return. That not in fact being a reasonable justification, instead we want to know whether state directed research and development is an efficient manner of gaining those desirable technological advances:

“If it fails, it goes to our pocket. And at the end of the day, it’s only money. That will not break the company, although it is going to be painful because we are investing one billion and a half at least in COVID right now.

But the reason why I did it was because I wanted to liberate our scientists from any bureaucracy. When you get money from someone that always comes with strings. They want to see how we are going to progress, what type of moves you are going to do. They want reports. I didn’t want to have any of that.

Basically I gave them an open chequebook so that they can worry only about scientific challenges, not anything else. And also, I wanted to keep Pfizer out of politics, by the way.”

Pfizer’s vaccine is the first to show decent results. It’s also the one that entirely rejected government funding through the emergency “let’s make a vaccine” fund.

There are costs and benefits to everything. As Bastiat pointed out, to be an economist is to search for that which is hidden in such calculations. The costs of - in part, only part of the costs - government direction of research include the costs of government oversight and management of research. It often enough being true that the costs of the bureaucracy are greater than the benefits of the aid.

Or, to repeat the point, we cannot look at technology and ask whether some of it was government funded and thus decide that said funding is a good idea. We must balance that with asking what didn’t we get because of the funding and also, well, would we have got it faster without the government bureaucracy?

At a more basic level we - our opinion, only our opinion - think that Mazzucato’s original research was funded in order to produce a justification for the European Union to own portions of the patents, technologies and companies that were funded by European Union funds. The political desire being to create a flow of “own funds” for the EU, a stream of future cash that did not depend upon recalcitrant national governments.

The model was Darpa, the American military funding agency. The problem with this being that Darpa, by design and specifically, does not take equity or other stakes in the things investigated or designed with its money. Precisely and exactly on the basis that having the bureaucrats trying to claim a portion of those cash benefits means a stultifying bureaucracy which limits, even prevents, the technological advance the money is being deployed to gain.

But there we are, commissioned research does often come up with the right answer, doesn’t it?

Spotting drivel in The Guardian from Tom Kibasi

Well, spotting innumeracy in The Guardian is not that unusual and full blown drivel has been known to appear. But when people propose a change to the tax system it really is incumbent upon them to understand the tax system we’ve already got, the one they’re desiring to change. This not being something apparent from Tom Kibasi here:

That’s why it’s time for a simple but radical and fair reform to tax: tax all income in the same way, whether it comes from wealth or from work. It goes against basic fairness that tax rates on income from share dividends or capital gains are much lower than those from employment.

A large share of the costs of coronavirus could be covered: abolishing capital gains and share dividend tax and instead putting all income on the income tax schedule would net around £90bn for the exchequer in five years. It would greatly simplify the tax system and it is almost impossible to argue that those who work hard for their income should be taxed more highly than those who do not.

Given that standard tax theory insists that capital income should be more lightly taxed than labour income that impossibility would seem to be most possible.

The background is that we like investment - it’s what makes the future richer. So, those who delay consumption now in order to make our children richer, why would we want to tax them for doing so? We can also argue about what is the revenue maximising rate of any one specific tax - the Laffer Curve peak is different for each tax of course. Empirical research seems to show that around the UK’s current CGT rate is that curve peak. We can even point out that there’s no inflation adjustment on capital gains (OK, there are some vestiges of past attempts still left but not in general) and we do need either that or a lower rate.

But put aside these logical points and consider dividend taxation. Tax rates are already at around income tax rates. By design too, that’s why we have the system we do have.

If we want to tax profits (see above, we might not want to) then conceptually we can do so at two points. It can be at the level of the company, the place where the profits are made. It can be in the hands of the recipients, the income or dividends received. Some places do it one way, others the other. We do it at both points but adjust the second tax rate to account for this. This is why dividend tax rates appear lower than income tax ones even as they aren’t.

Take £100 in profits that have been made. These pay 18% at the corporate level this year. There is now £82 to be paid out as dividends. You can receive up to £2,000 without paying further tax - this is for administrative convenience. After this if you’re a basic rate taxpayer there is 7.5% to be collected. That is, a total tax take of (0.075x82 plus 18) £24.15. If a higher rate payer then the rate is 32.5% so £44.65. If additional rate 38.1%, so £49.24. And those tax sums translate over into rates, of course, giving total tax rates of 24%, 44% and 49%*. Which are not, the numerate will note, lower than income tax rates.

We can check this too. Imagine the business is organised as a partnership of some kind (LLP say). There is no corporation tax and profits pay simply normal income tax. Which gives, for that same distribution of £100 in profits, total rates - dependent upon the other income of the recipients - of 20%, 40% and 45%.

To insist that dividends should pay the same rates of tax as labour income isn’t, in fact, desirable for those logical and theoretic reasons. But to demand that change without knowing that they already do, and more, is, well, what should we call it? Is drivel too harsh?

*We’re willing to be corrected on the details here but not the general principle.

Protecting cultural heritage or stealing?

The preservation of culture, a culture, has its value, of course it does. A useful indication of this being when people, voluntarily, pay the necessary prices to preserve said culture. As and when the external culture changes, so that the society around decides that such preservational prices are no longer worth paying then, by definition, the preservation isn’t worth it by the standards of that surrounding society.

Of course, it’s always possible to disguise this:

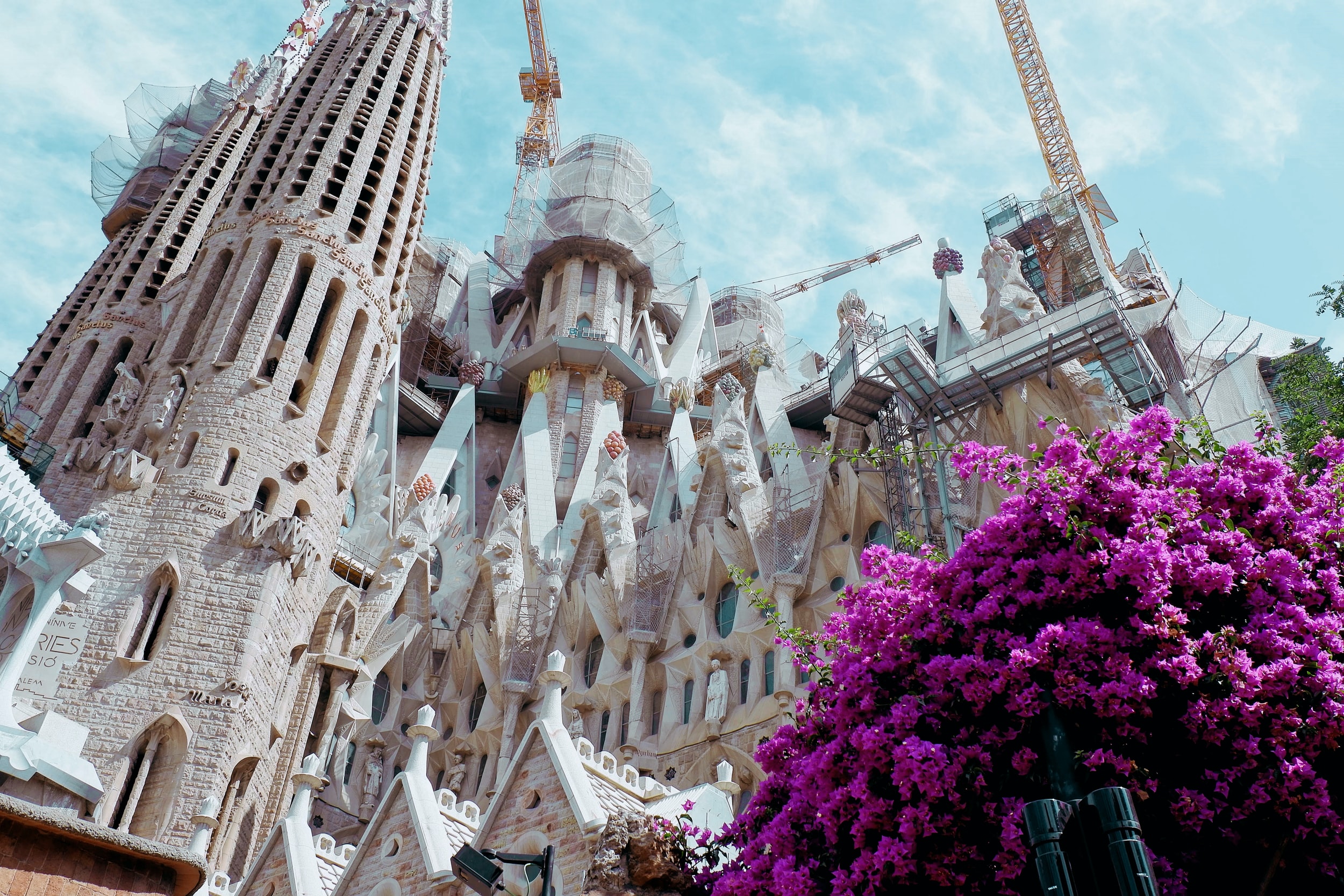

Barcelona council has come to the rescue of some of the city’s most emblematic and best-loved bars by adding them to the list of protected sites and buildings. However, thanks to Covid-19 restrictions, you won’t be able to get a drink in any of them for at least the next few weeks.

The city has added 11 bodegas to the list of 220 shops that are considered part of the city’s cultural heritage. The move has been widely welcomed, though it comes too late to save many small businesses, from toy and book shops to grocery and furniture stores, that were part of the fabric and essence of the city but were forced out by soaring rents. In most cases they have been replaced by chain stores.

How have they been saved?

"We cannot protect 100% the commercial activity but we can make it difficult for other activities that do not harmonise with the identity of the street to come in," said Antoni Vives, Barcelona's Deputy Mayor for Urban Habitat. With regard to the content of the property, "the conclusion is that the furniture and the property should go together" said Civit. Each of the 228 protected shop buildings will possess a technical sheet specifying everything hitherto that must be safeguarded and "in case something has to be moved, how it has to be moved" he added.

The saving involves restrictions upon change of use through that insistence upon keeping those internal things like furniture and so on.

That is, the owners of the sites may not change use in order to gain the higher value that stems from such. Or, as we might put it, the property of landlords is stolen in order to maintain the public pleasures of old shops and bars. The benefits of preserving those things objectively not worth preserving are socialised while the costs are privatised.

That is, the answer to the headline is yes. It is both cultural preservation and stealing.

There is an answer to this too. If some group of people - any group of them - decide that something is worth preserving then raise the money and go buy it. Can’t raise the money? Then no one actually wants the preservation enough, do they?

Don’t nick it through regulation.

Clarity of thinking is essential

We note this not to be mean to Mr. Colville for Robert is a thoroughly nice chap on the right side of most questions. However, this cannot pass without comment:

On financial services, for example, the EU is not going to give us unrestricted long-term access to its markets…

That’s not the right way ‘round to think of it. The purpose of trade is to be able to consume those imports. Thus the correct viewpoint is not will they open their markets to us but whether they will have access to the lovely things we make.

The City is the prime financial market in Europe and arguably the world. The question is not whether those financial firms can sell in Europe, it’s whether Europeans gain access to the financial services they desire.

This is true as a larger point about all trade restrictions, be they tariffs, phytosanitary rules, trivia over documentation or quotas. The only reason to have any of them is to deny consumers what they so obviously desire - for, of course, if they were not desired then there would be no point in having the restrictions.

Colville is probably correct in that there will at least be a determined effort by the European Union to stop firms and others in the rEU from gaining access to the largest, deepest, most efficient and most liquid capital market in the world. Our insistence upon describing the attempt in the correct manner does at least show how damn stupid the idea is.

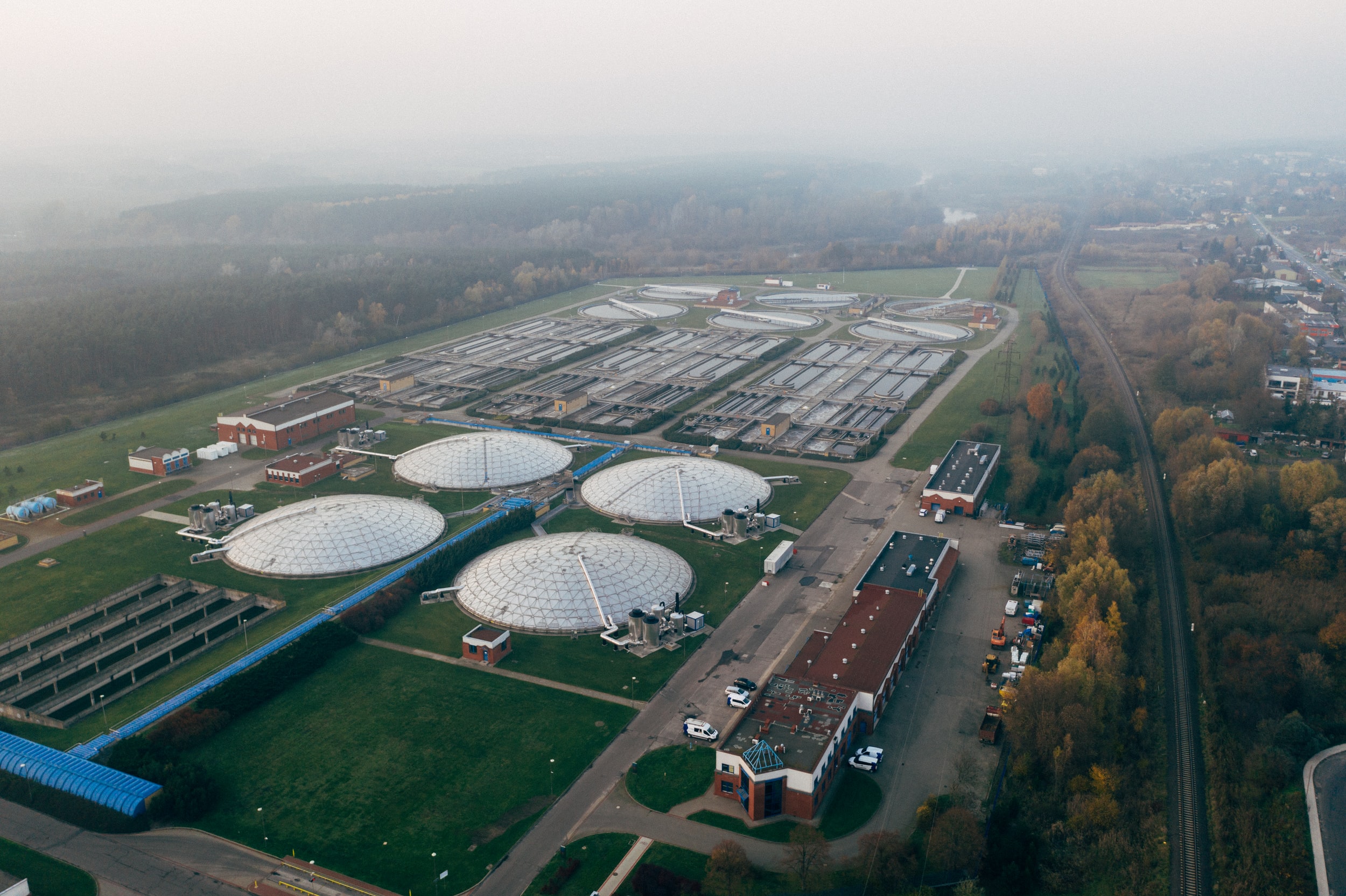

Surfers against sewage

We’d suggest that Surfers Against Sewage do a little work and acquaint themselves with the basics of cost benefit analysis:

Water companies discharged raw sewage into bathing water beaches almost 3,000 times in the past year, polluting the environment and risking public health, new analysis shows.

The discharges took place all over England and Wales, including at some of the most popular beaches.

The study by Surfers Against Sewage, which publishes data on sewage releases as they occur, examines the notifications by water companies of effluent discharges over 12 months.

The claim is that this led to 156 cases of gastroenteritis and the like. The solution to which is:

Our ambition at Surfers Against Sewage is to end sewage discharge into UK Bathing Waters by 2030.

More specifically, they are talking about storm drainage and sewage. Trying to insist that when the heavens open there is no overflow at all - their insistence - from said sewage system into the standard water run off from the weather is going to be somewhere between vastly expensive and impossible.

That is, the cost of gaining the benefit of 156 dickey tummies fewer seems more than a little excessive. We cannot do everything, cannot be perfectly clean, and we’d propose that there are more important things to devote resources to than this.

We’d also suggest that a certain knowledge of finance could be useful:

We need to see legally-binding sewage emission reduction targets and subsequent investment that bring about an end to sewage pollution.

....

Ultimately, ambitious and progressive investment is needed to separate our surface water from sewage treatment infrastructure to truly protect the environment. It is incumbent on water companies to identify the pathway to make this happen. Perhaps instead of sickening dividend pay outs...

Why would people put more capital in if they weren’t going to gain a return on it? And no, shouting that the water companies should be nationalised again won’t work either. For when the government did own and run them it invested very much less than the privatised companies have done. Which was the reason for the sell off in fact, in order to bring in the capital necessary to raise water standards, capital that government wasn’t willing to assign.

Which is an interesting point really. If it can’t even pass a government cost benefit analysis with people spending other peoples’ money on other people then possibly this really is something we shouldn’t be attempting.

It's easy - and enjoyable - to make fun of Johnny Foreigner

An amusement from France:

Sales of foie gras fell 12 per cent last year and the pandemic has made matters worse. Producers are expecting a 20 per cent drop this year compared with last year. In response, the government has allowed unlimited cut-price offers on foie gras, while outlawing advertisements for the cheap deals.

You may sell at any price you wish but cannot tell anyone about it. The contorted logic continues, as this is a rule that applies only to fois gras.

Other comestibles may not be discounted in this manner:

Retailers were banned from selling more than a quarter of any product at a knockdown rate or at less than 34 per cent off their list price.

The reason why:

The law was designed to ensure “a fair price” for farmers and “healthy, sustainable food accessible for everyone”. It involved a curb on the supermarket promotions that Mr Macron blamed for dragging down prices, leaving a third of French farmers with an income of less than €4,200 a year.

Consumers may not, by law, be made better off in order to protect producers. What larks given the most odd moral economy of Johnny Foreigner, eh?

Except perhaps we shouldn’t laugh at Mr. Foreigner too much. Our own polity is insisting that consumers may not be made better off in order to protect those producers. This is what all that fuss about food standards, chlorinated chicken and so on, concerns. Certain other foreigners can produce food that we may wish to consume. Or not consume, as the taste takes us. We are to be banned by law from making that choice in order to protect domestic farmers, those producers.

The retailers are also restricted in their ability to tell us of sales and offers like Bogofs. The same twisted logic but as it has been for centuries now our absurdities are better than those of the French, aren’t they, entirely and quite, quite, different.

Actual logic would suggest that we pluck the beam from our own eye. Free trade, a free market, in food to the benefit of consumers. For making us consumers out here better off is the entire point of our having an economy in the first place.

It's the management of the NHS that fails

Of course, having a near Stalinist bureaucracy is unlikely to lead us to a well managed service. But recent findings about the impact of Covid on cancer treatments should give pause:

However, new analysis published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) found that increasing the wait to surgery from six to 12 weeks would increase the risk of death by around nine per cent.

The scientists at Queen’s University in Ontario and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine found that even a delay of less than four weeks could not be justified.

The calculated a four per cent increased risk of death for a two-week delay for breast cancer surgery.

Across a wider range of cancers, a month’s delay to the start of treatment more broadly, such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy, was associated with an increased risk of death of up to 13 per cent.

Of course, we all understand why treatments have been recently delayed. But the message here is that cancer treatment should be started stat. The very thing that the NHS does not do:

You should not have to wait more than 2 weeks to see a specialist if your GP suspects you have cancer and urgently refers you.

In cases where cancer has been confirmed, you should not have to wait more than 31 days from the decision to treat to the start of treatment.

This being a promise the NHS doesn’t live up to either.

This not being a matter of some scarcity of resources. The same number of people get treated for the same number of cancers. It’s simply bad deployment of those resources - management in an inflexible system - which makes people wait. And so, more of them die.

There is a reason why the NHS comes near bottom of rich world health care systems when measured by “mortality amenable to health care”. The reason being that structure of the NHS.

How excessively cool is this?

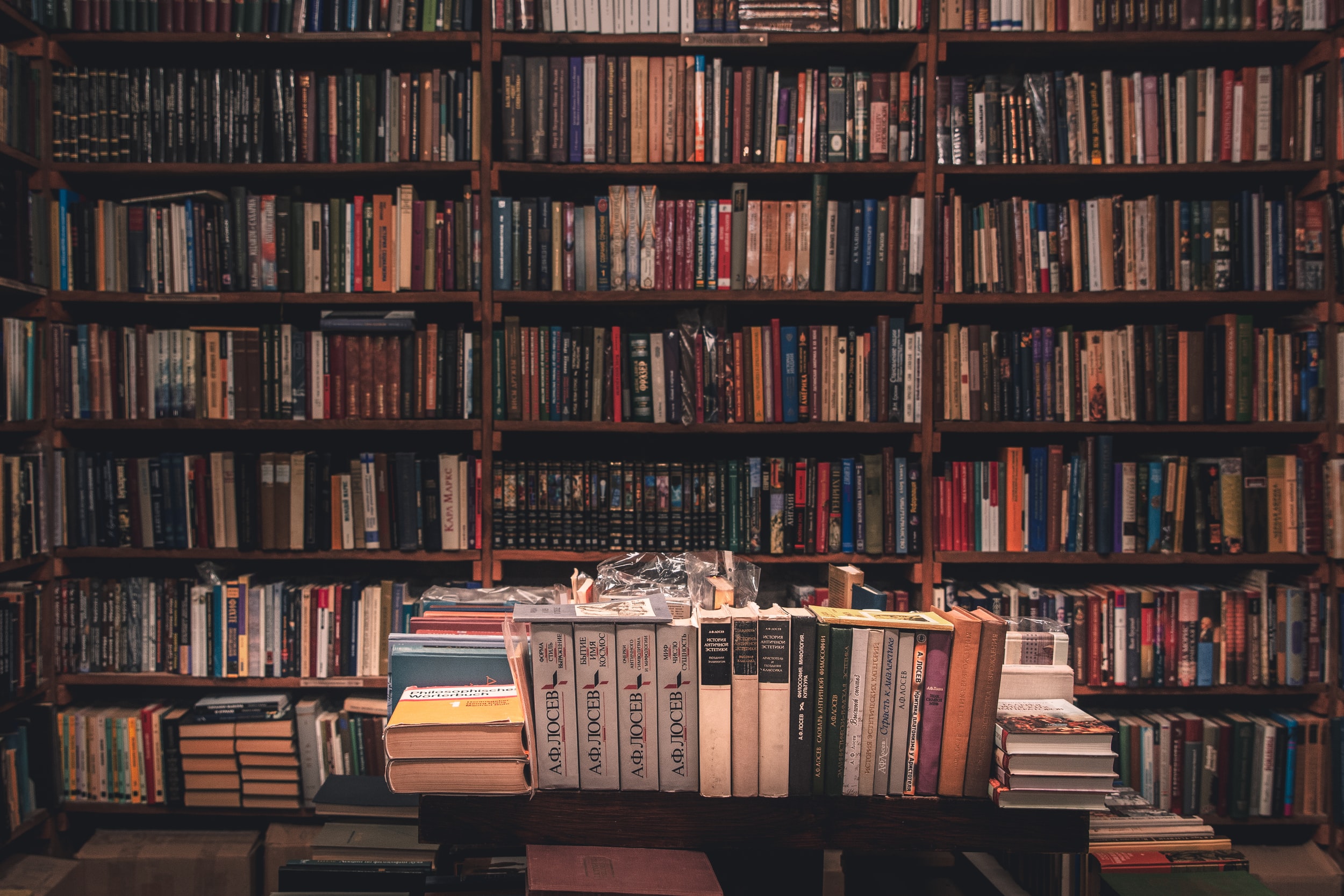

Simon Jenkins is terribly excited by a new website where it is possible to pay full price for books. We share that excitement:

Good news from the high street. We don’t often read those words, least of all courtesy of the internet. The UK opening on Monday of the Bookshop website is a blood transfusion for independent bookshops and one from which all retailers can learn. The website is a mail-order circumvention of Amazon, selling books under the flags of more than 130 independent booksellers. Buyers order their book at a slightly discounted price after “entering” their chosen front door on the site and the shop duly receives the 30% bookseller’s margin.

Isn’t that good news? Not that we would recommend you use the site, nor that you don’t. It’s something entirely for you to decide for yourself. Which is exactly what provides the excitement in our little corner of the world.

Some of us are rather - from very to more perhaps - interested in what we ourselves have got to shell out to gain access to something, books being just an example of the larger point. Others of us are rather - from very to more perhaps - interested in the effects upon the provider. This leads to a certain bifurcation, in that some of us shop entirely on the cash price, others on the structure of the delivery system.

Of course, this changes at the extremes, very few indeed would agree that cheaper through the chattel slavery of book retailers is worthwhile - although there will always be a few - nor that £100 a volume is worth it to ensure a decent living standard for those who pack the boxes.

So, consumers have different desires, at least partially so, how best to accommodate that? Well, the only possible manner is that the different ways of achieving the goal - book retailing in our example - are tried out and we’ll see which best contributes to consumer utility. As we’ve already defined that utility as differing across people this insists upon our having many different methods of book retailing.

That is, this is all proof of the basic fact that it is free markets - the definition being that people get to try out different methods of assuaging that consumer utility - are the best possible system. Precisely and exactly so that those who wish to can pay near full price for their books even in the face of others offering greater discounts.

Isn’t that cool?

One of those weird occasions when we find ourselves agreeing with Polly Toynbee

Quite which time honoured phrase to use here - from the mouths of babes and sucklings or possibly something about emperor’s new clothes - doesn’t matter so much as the actual point being made.

I doubt the British government has learned the lesson: never again run down the country’s public health defences.

Entirely so, we too think that government won’t learn the lesson here. Which is that communicable diseases are a problem, one that needs management and the state an its employees are a vital part of that solution.

Which means that whatever - and whoever - it is that replaces Public Health England should be restricted to working upon the problems that stem from communicable diseases. Rather than the recent decades long haranguing us all about lifestyle diseases. What we smoke, eat and drink are important things, no doubt about it, but they are also personal and both the benefits and costs accrue to us as the individuals doing those things. They are not public health matters that is, even as they are matters to do with the health of the public.

We should indeed return to where the public health authorities deal, exclusively, with those matters where there are third party effects to decisions. To sewage and drains, to epi- and pan- demics, to where public actions, collective public actions that is, are actually required.

That is, let us have a public health service instead of bureaucrats mithering us about the size of chocolate bars.

Tune in some time next decade for our next agreement with Ms. Toynbee.