It's rare to see things so explicitly stated

Owen Hatherley tells us of that exciting future when there’s more council and social housing:

We have long known what to do about a crisis of housing affordability: have local authorities build housing at social rents. The pandemic hit at a time when council housing had started to have a modest revival, including in Bristol, where several councillors are members of Acorn renters union. It’s possible that a mixture of council housing programmes, co-operatives and councillor support for tenants’ organisations could presage a future for the Labour left among those who rent their homes.

That seems odd - why would people vote left to gain stuff if they’re already gaining the stuff to be gained by voting left? The answer:

Whether you own or rent your home is a surer indication of voting preferences than your age: a tenant in their 60s is no more likely to vote Conservative than one in their 30s.

We tend to think this is a bad idea. Designing the housing system of the country around who gets to be an MP as a result doesn’t meet our own desire for said housing system.

Which is that people gain the housing they desire and thus housing becomes an entirely non-political issue. This does apply to tilting the system one way through ownership and the other through rental tenancies. This also means solving that affordability problem and we’ve pointed out how to do that often enough. Issue enough planning permissions that a planning permission has no value. A house will therefore approach in value the marginal cost of production - something like £100,000 to £120,000 for a nice little three bedder on a reasonable garden plot. For that is the land and construction cost when shorn of the price of the artificial scarcity of that permission to build a house.

This rather highlighting one of the difficulties with politics as a manner of dealing with matters. If problems actually get solved then there’s no ability to use the existence of the problem as a route to gaining political power. Which is, we aver, why so many solvable problems don’t get solved by the political process.

You first mateys, you first

The insistence that we should all go do something that the proposers, themselves, are not willing to do can make sense at times. Then again, it can at times be evidence of more than usually woolly thinking. We’re in that second part of the logical diagram here:

Politicians from the UK, Germany and Spain have written a letter to Boris Johnson, calling for a four-day week to be implemented “now” so countries can begin the process of combatting the economic consequences of Covid-19.

As the article itself refers to, in a point we’ve made before, there’s a problem here. Shorter working hours are something we do when we’re richer, leisure being a luxury good. Covid has made us poorer, this isn’t an obvious time to be considering working less.

However:

“For the advancement of civilisation and the good society, now is the moment to seize the opportunity and move towards shorter working hours with no loss of pay.”

Hmm, well.

The coalition that sent the letter includes: John McDonnell, former shadow chancellor of the exchequer in the UK; Katja Kipping, the chair of Die Linke party in Germany; Íñigo Errejón, an MP in Spain’s Más País party; Green party MP Caroline Lucas; and Len McCluskey, general secretary of the Unite union.

All of those people employ people. Most gain access to generous public funds to employ staff. There are budgets that they may not exceed, of course. So, given that this is such a good idea they can offer their staff those four day weeks - with no loss of pay - and we’ll see how it works out, shall we?

After all, they are insisting this is what we all should - must - do. So there’ll be no shyness about proving the wondrousness of it first, will there?

We await their report with interest.

To return to the costs of bureaucracy

Yesterday we noted that excessive health and safety bureaucracy leads to a reduction in health and safety. Today there is an international example of the same thing:

A new polio vaccine has now been created to deal with these cases. It also uses a weakened live virus, but it has been genetically engineered to prevent it from mutating and becoming harmful. This new vaccine is now being tested, with funds provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and others.

However, the vaccine is not yet licensed. Not surprisingly, this is causing frustration as vaccine-derived polio cases rise alarmingly. As a result, many doctors and scientists are now urging the World Health Organization to use its emergency-use listing process to give them the go-ahead to use the vaccine now.

We have the new and necessary vaccine. We even know it works. But the bureaucracy hasn’t jotted and tittled as yet and therefore there are those extra costs. Bureaucratic regulation has costs, here, as with rail safety, in terms of lives.

It’s also possible for bureaucracy to entirely negate the aim:

The government’s plan to insulate England’s draughty homes is faltering because builders and installers are failing to sign up, leaving thousands of households unable to access the £3bn green home grants.

No, they’re entirely able to access the grants. They just can’t spend them:

According to government data, only 1,174 installers have signed up to the scheme, which started on 30 September, while more than 36,000 householders have applied for the grants, which will be available until March.

So why the shortage of providers?

Andrew McCausland, the director of Wirral Property Group, spent about £6,000 and an estimated 160 hours of unpaid work to get his team accredited. He felt the process was worthwhile given the size of his business, but said smaller firms could find it more of a challenge.

“It has taken me many days to work through the requirements of the various certifying and accrediting bodies and arrange suitable insurance cover – the whole process has been very time-consuming for me to navigate,” he said. “I would advise other builders to only get involved if they have dedicated administrative support on the payroll.”

All rather come and see the bureaucracy inherent in the system, isn’t it?

At some point this urge to enforce box ticking becomes counterproductive. Those who could actually be doing things either won’t, because of the paperwork, or can’t, because of the paperwork. The sadness of the current system seems to be that we have passed that point of it all being counterproductive. A bonfire of the regulations is therefore necessary. Even if we’ve missed that November 5th chance for a bonfire of the regulators. For this year….

It's possible to have entirely too much safety

On that Hayekian basis that knowledge is local, an example from the frontlines of rail safety:

Network Rail has in place a scheme for managing track safety training and assessment. This is overseen by an outside body contracted by Network Rail – the National Skills Academy for Rail Engineering.

On the face of it, this is a sensible scheme as the whole thing is designed to prevent fraudulent access to the track. Yes, back in the bad old days, track safety tickets were being bought and sold in the local pub, so something had to happen, hence the Sentinel scheme.

The problem, however, is that eventually a system can become too top heavy. There then becomes a conflict between getting the job done and the onerous requirements for a safe system of work with its plethora of paperwork. I recall having a ream of paperwork just to do a track safety walkout during training activities, most of which was entirely useless to me. I even had to do a task brief. This consisted of “we are going for a walk to look at the track and show you what’s what.” Yes, really.

As a track safety trainer and assessor, I frequently came across track workers who told me that the requirements simply didn’t happen as laid out by Network Rail because they got in the way of getting the job done and that if they complained they would be out of work.

Yes, of course everyone wants rail staff to be safe. But regulations and procedures that aren’t followed, because they’re too intrusive, don’t do that.

The above being in relation to an accident that killed two such workers. And follows some 44 reports of the regs being that too intrusive to actually add to safety.

At the very least this should - but probably won’t - engender some humility among the bureaucrats that infest our lives. There is a limit to the power of paper wielding to make our lives better, almost certainly one we’ve already blown through. So perhaps we can have less of it all? To, you know, make people safer, stop them dying?

Lockdowns aren't all that effective

A central contention of those who rule is is that we must be told what to do. For we are not wise, nor omniscient, while they are. Or at least closer to such distinguished states than we are. This does rather grate with Hayek’s great point, that knowledge is local, not centralised. So, in times like these, times of grand management of society by those oh so knowledgeable rulers, we’d like the occasional empirical test of either side of the contention.

Which is just what we’ve got and the answer is that lockdowns - being told what to do with that firm thwack of central power - isn’t all that effective.

Our analysis indicates that older cohorts cut their expenditures on high-contact goods and services indeed by much more than younger cohorts in all epidemic months (see Figure 1). For example, when infections peaked in April, consumers in their seventies cut their expenditures on high-contact goods by 61.8% but only by 28.4% on low-contact goods. The corresponding cuts in expenditures for people younger than 49 are 26.0% and 19.2%, respectively. Older cohorts hence cut their expenditures on high-contact goods much more aggressively than younger cohorts in all of the epidemic months. These cuts are particularly pronounced in April.

The construction is that civil servants won’t have taken a hit to their incomes in the spring. Therefore changes in purchases will reflect changes in desires, not abilities, over consumption. We know, and knew then, that older age groups were much more at risk. We also know, and knew then, that infection - this being pretty obvious with an infectious disease - depended upon contact with others.

So, if older people - among those unconstrained by changes in income - reduced their exposure, measured by expenditures associated with social mixing, more than the younger we have evidence of behavioural change being driven by local knowledge, not central. If it was all about lockdowns (and one of us has been living through this Portuguese experience, directly) then the changes in expenditure would show no age difference.

Or, as we might put it - should perhaps - tell people there’s a danger they react to it. Rationally react to it too. More detailed management of activity is not, or perhaps less, needed.

There is a flip side to this too, which is that if economic behaviour changes because of the pandemic itself then the economic damage of the lockdown is less. For some to all of that change in economic activity is, as is the contention here itself, a result of reactions to the pandemic not to the lockdown.

Again as we might - or should - put it we’re all adults out here and advice to us is just great but we don’t need micro-management of our lives.

The importance of property rights

There’s something entirely true being said here:

However, free markets do not exist in a vacuum and need a legal framework that includes strong property rights and freedom from corruption

Quite so, quite so. Property rights meaning, in the end, the ability to dispose of said property as one wishes. If you can’t do that then it’s not really, fully, yours. If, for example, it requires the voted agreement of the workforce to be sold then in an important manner ownership is split with the workforce. If it requires the acquiescence of the government then ownership is split with whatever group of baby kissers happens to be in office.

This week, the Government introduced the National Security and Investment Bill (NSIB), which will allow it to block the takeover of companies in 17 key sectors, including data infrastructure, communications, quantum technology, advanced materials and computer hardware.

This is thus a reduction in those property rights.It also put limits on free markets – the core of the capitalist system that has generated our wealth.

However, free markets do not exist in a vacuum and need a legal framework that includes strong property rights and freedom from corruption – so restrictions such as those introduced by the NSIB fit into this framework.

This is thus something we should not be doing as it undermines those property rights which are the basis of the capitalist and free market system that has made us one of the richest societies ever to bestride the globe.

It is, clearly, possible to think that perhaps this sort of management should apply to the design of the latest super-tank or hypersonic drone. But:

One recent example of this was when a Chinese gaming firm bought dating app Grindr.

After being developed in Los Angeles, it was it was bought by Beijing Kunlun in 2016 for $93m (£71m). The deal was eventually examined by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, which told the Beijing-based parent company that its ownership of Grindr constituted a national security threat.

The fear was that Chinese actors could use personal data collated by the app to compromise or influence individuals in Western countries. Following US pressure, Grindr was sold in March this year to US-based San Vicente Acquisition.

Which bloke is seeking which other bloke for a quickie is no longer - unlike in Turing’s time - such a matter of national security. But that is clearly how such laws are going to be used for they already are so used.

As so often this accrues power to the state the effect of which will be to make us all poorer.

Don’t do it.

An error of logic on climate change

Well, this is good news:

Reaching net zero carbon emissions in the UK is likely to be much easier and cheaper than previously thought, and can be designed in such a way as to quickly improve the lives of millions of people, a senior adviser to the government has said.

Chris Stark, the chief executive of the Committee on Climate Change, the UK’s independent statutory adviser, said costs had come down rapidly in recent years, and past estimates that moving to a low-carbon economy would cut trillions from GDP were wrong.

“Overall, the cost is surprisingly low – it’s cheaper than even we thought last year when we made our assessments. Net zero is relatively low-cost across the economy,” he said.

Leave aside whether it needs to be done at all. If it does then it being cheaper is good, if it doesn’t but they’re going to do it anyway then it being cheaper is good.

The error of logic is here:

“But that rests on action now. You can’t sit on your hands and imagine it’s just going to get cheaper by magic.”

Renewable energy prices have plunged in the last decade, putting solar and wind at lower cost than fossil fuels in many countries, spurring a global boom in clean power.

So, how has this been done then? By people out there making cheaper windmills and cheaper solar panels. By, that is, free market competition among capitalist, profit hungry, producers. Sure, we can say that some kickstarting was necessary. We tend to think that not much was and that this has all been done in a grossly expensive manner but, you know, opinions and all that.

But consider the situation now. The claim, at least, is that these solar and wind things are cheaper than fossil. So, the competition remains among those capitalist, profit hungry, producers to continue to gain market share. Which they will do by continuing the technological development of those already profitable - they must be, otherwise the claim of their being cheaper cannot be true - products of theirs.

That is, even if it is true that something had to be done that something has been done. Our correct response now is exactly to sit on our hands because it is all going to get ever cheaper. The magic being that combination of the capitalist lust for profits combined with the competition of free markets.

Or, as we might put it, exactly the success claimed by those who call for intervention means the end of the need for the intervention. We’ve already solved the problem, we’re done.

Oh, and as to our claim that this has all been done too expensively. Back in the 1990s people like Bjorn Lomborg were pointing out that solar was getting cheaper at 20% a year and that that, by the 2020s, would mean it was cheaper than fossil fuels and so the problem would be solved. Here we are, 2020s, the claim is that solar is cheaper and the problem is well solved. We’ve spent a fortune getting here and arguably we needed to spend nothing at all to do so. Because that technological trend, the 20% pa reduction in the price of solar, hasn’t changed, not so as we’ve been shown at least, as a result of all that spending.

Why not stop making that mistake and just leave it to that capitalist free marketry that actually has been solving the problem so far?

Pfizer's vaccine is something of a blow for the Mariana Mazzucato thesis

Mariana Mazzucato tells us that technological advance comes from wise investments by the omnisicient and beneficial state. Her proof is that some technological advances have come from investments by the state. One answer to this is that given the state’s appropriation of 30 to 40% of everything we’d rather expect to gain the occasional snippet of a public good in return. That not in fact being a reasonable justification, instead we want to know whether state directed research and development is an efficient manner of gaining those desirable technological advances:

“If it fails, it goes to our pocket. And at the end of the day, it’s only money. That will not break the company, although it is going to be painful because we are investing one billion and a half at least in COVID right now.

But the reason why I did it was because I wanted to liberate our scientists from any bureaucracy. When you get money from someone that always comes with strings. They want to see how we are going to progress, what type of moves you are going to do. They want reports. I didn’t want to have any of that.

Basically I gave them an open chequebook so that they can worry only about scientific challenges, not anything else. And also, I wanted to keep Pfizer out of politics, by the way.”

Pfizer’s vaccine is the first to show decent results. It’s also the one that entirely rejected government funding through the emergency “let’s make a vaccine” fund.

There are costs and benefits to everything. As Bastiat pointed out, to be an economist is to search for that which is hidden in such calculations. The costs of - in part, only part of the costs - government direction of research include the costs of government oversight and management of research. It often enough being true that the costs of the bureaucracy are greater than the benefits of the aid.

Or, to repeat the point, we cannot look at technology and ask whether some of it was government funded and thus decide that said funding is a good idea. We must balance that with asking what didn’t we get because of the funding and also, well, would we have got it faster without the government bureaucracy?

At a more basic level we - our opinion, only our opinion - think that Mazzucato’s original research was funded in order to produce a justification for the European Union to own portions of the patents, technologies and companies that were funded by European Union funds. The political desire being to create a flow of “own funds” for the EU, a stream of future cash that did not depend upon recalcitrant national governments.

The model was Darpa, the American military funding agency. The problem with this being that Darpa, by design and specifically, does not take equity or other stakes in the things investigated or designed with its money. Precisely and exactly on the basis that having the bureaucrats trying to claim a portion of those cash benefits means a stultifying bureaucracy which limits, even prevents, the technological advance the money is being deployed to gain.

But there we are, commissioned research does often come up with the right answer, doesn’t it?

Spotting drivel in The Guardian from Tom Kibasi

Well, spotting innumeracy in The Guardian is not that unusual and full blown drivel has been known to appear. But when people propose a change to the tax system it really is incumbent upon them to understand the tax system we’ve already got, the one they’re desiring to change. This not being something apparent from Tom Kibasi here:

That’s why it’s time for a simple but radical and fair reform to tax: tax all income in the same way, whether it comes from wealth or from work. It goes against basic fairness that tax rates on income from share dividends or capital gains are much lower than those from employment.

A large share of the costs of coronavirus could be covered: abolishing capital gains and share dividend tax and instead putting all income on the income tax schedule would net around £90bn for the exchequer in five years. It would greatly simplify the tax system and it is almost impossible to argue that those who work hard for their income should be taxed more highly than those who do not.

Given that standard tax theory insists that capital income should be more lightly taxed than labour income that impossibility would seem to be most possible.

The background is that we like investment - it’s what makes the future richer. So, those who delay consumption now in order to make our children richer, why would we want to tax them for doing so? We can also argue about what is the revenue maximising rate of any one specific tax - the Laffer Curve peak is different for each tax of course. Empirical research seems to show that around the UK’s current CGT rate is that curve peak. We can even point out that there’s no inflation adjustment on capital gains (OK, there are some vestiges of past attempts still left but not in general) and we do need either that or a lower rate.

But put aside these logical points and consider dividend taxation. Tax rates are already at around income tax rates. By design too, that’s why we have the system we do have.

If we want to tax profits (see above, we might not want to) then conceptually we can do so at two points. It can be at the level of the company, the place where the profits are made. It can be in the hands of the recipients, the income or dividends received. Some places do it one way, others the other. We do it at both points but adjust the second tax rate to account for this. This is why dividend tax rates appear lower than income tax ones even as they aren’t.

Take £100 in profits that have been made. These pay 18% at the corporate level this year. There is now £82 to be paid out as dividends. You can receive up to £2,000 without paying further tax - this is for administrative convenience. After this if you’re a basic rate taxpayer there is 7.5% to be collected. That is, a total tax take of (0.075x82 plus 18) £24.15. If a higher rate payer then the rate is 32.5% so £44.65. If additional rate 38.1%, so £49.24. And those tax sums translate over into rates, of course, giving total tax rates of 24%, 44% and 49%*. Which are not, the numerate will note, lower than income tax rates.

We can check this too. Imagine the business is organised as a partnership of some kind (LLP say). There is no corporation tax and profits pay simply normal income tax. Which gives, for that same distribution of £100 in profits, total rates - dependent upon the other income of the recipients - of 20%, 40% and 45%.

To insist that dividends should pay the same rates of tax as labour income isn’t, in fact, desirable for those logical and theoretic reasons. But to demand that change without knowing that they already do, and more, is, well, what should we call it? Is drivel too harsh?

*We’re willing to be corrected on the details here but not the general principle.

Protecting cultural heritage or stealing?

The preservation of culture, a culture, has its value, of course it does. A useful indication of this being when people, voluntarily, pay the necessary prices to preserve said culture. As and when the external culture changes, so that the society around decides that such preservational prices are no longer worth paying then, by definition, the preservation isn’t worth it by the standards of that surrounding society.

Of course, it’s always possible to disguise this:

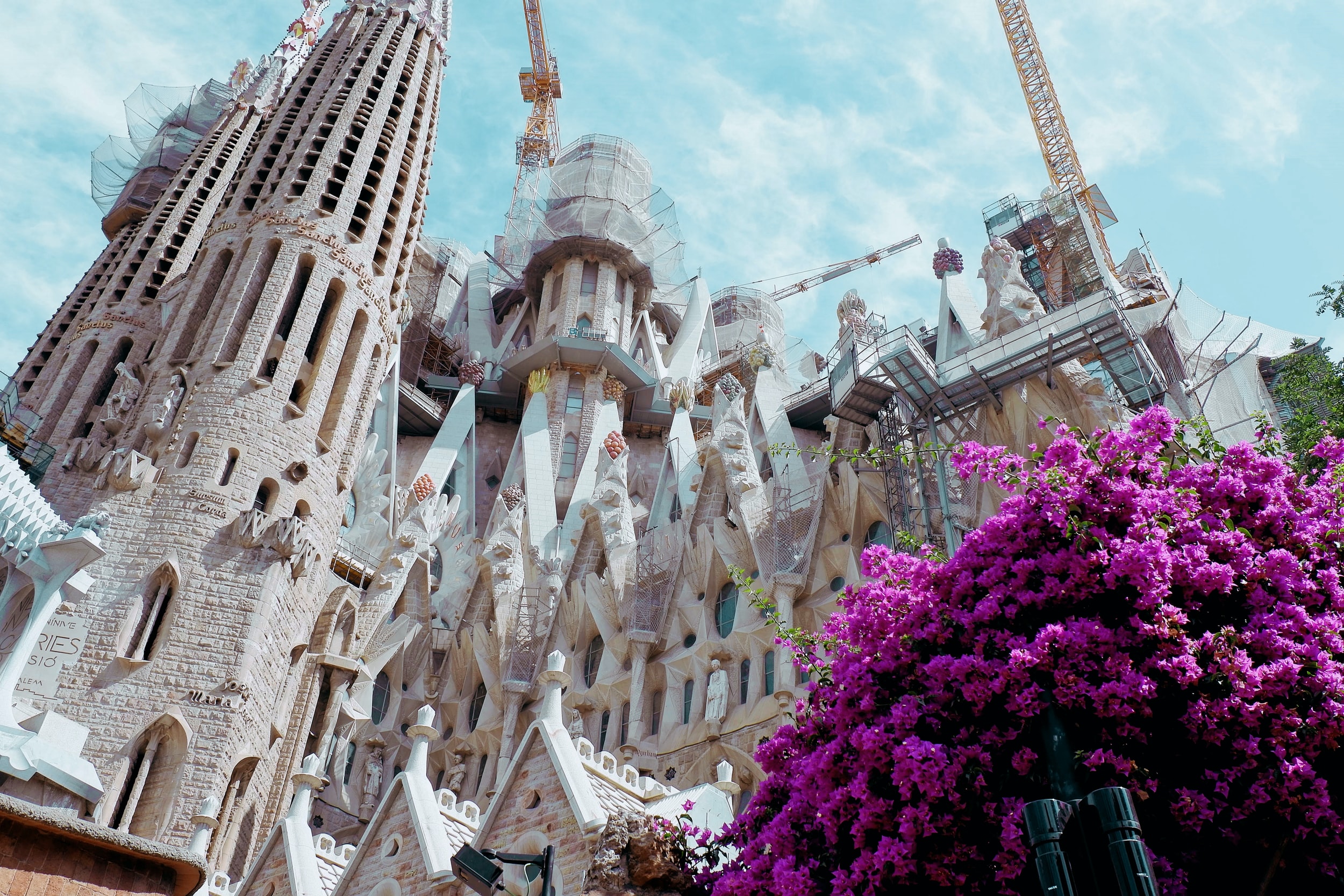

Barcelona council has come to the rescue of some of the city’s most emblematic and best-loved bars by adding them to the list of protected sites and buildings. However, thanks to Covid-19 restrictions, you won’t be able to get a drink in any of them for at least the next few weeks.

The city has added 11 bodegas to the list of 220 shops that are considered part of the city’s cultural heritage. The move has been widely welcomed, though it comes too late to save many small businesses, from toy and book shops to grocery and furniture stores, that were part of the fabric and essence of the city but were forced out by soaring rents. In most cases they have been replaced by chain stores.

How have they been saved?

"We cannot protect 100% the commercial activity but we can make it difficult for other activities that do not harmonise with the identity of the street to come in," said Antoni Vives, Barcelona's Deputy Mayor for Urban Habitat. With regard to the content of the property, "the conclusion is that the furniture and the property should go together" said Civit. Each of the 228 protected shop buildings will possess a technical sheet specifying everything hitherto that must be safeguarded and "in case something has to be moved, how it has to be moved" he added.

The saving involves restrictions upon change of use through that insistence upon keeping those internal things like furniture and so on.

That is, the owners of the sites may not change use in order to gain the higher value that stems from such. Or, as we might put it, the property of landlords is stolen in order to maintain the public pleasures of old shops and bars. The benefits of preserving those things objectively not worth preserving are socialised while the costs are privatised.

That is, the answer to the headline is yes. It is both cultural preservation and stealing.

There is an answer to this too. If some group of people - any group of them - decide that something is worth preserving then raise the money and go buy it. Can’t raise the money? Then no one actually wants the preservation enough, do they?

Don’t nick it through regulation.