A victory for the liberal ideal at Cambridge University

Most who currently describe themselves as liberals - in that American sense becoming more common in England - will dislike this recent event. We, being actual liberals, applaud it entirely. For it the victory of the base liberal ideal:

Cambridge University dons have prevailed in a free speech row after voting down an attempt by university chiefs to force them to be “respectful of the diverse identities of others”.

The change is from “respect” to “tolerate”.

A group of academics managed to force a ballot on a series of amendments including that the phrase “respectful of” is replaced with “tolerate”.

….

The amendment proposing ‘respect’ should be replaced with ‘tolerate’ passed by 1,378 votes to 208, while the other amendments proposed by Dr Ahmed passed by 1,243 to 311 and 1,202 to 342.

A liberal polity is one in which we all get to do our own thing - absent those third party effects re noses and fist swinging - and everyone else has to put up with our doing so.

To insist that others respect our decisions - or the way we’re made - over sexuality, race, culture, preferences, utility or anything else is not to be liberal. For that is to impose upon the observer a duty which is in itself illiberal. That they have to put up with, tolerate, is the definition of that desired liberality.

After all, if we’ve got to respect someone who believes in some idiocy like Marx’s Labour Theory of Value is to place a substantial burden upon those of us who have grasped the marginalist revolution. That we’ve got to tolerate people who believe idiocies is just part of the human condition.

Obesity? Round up the usual suspects

You know the form: government sells off school playing fields, children get fat, government must be seen to do something but poor old Matt Hancock is preoccupied with Covid, so he rounds up usual suspects, namely junk food and advertising. He shows no interest in analysing the real causes of the growth of obesity nationwide, starting in childhood, continuing through life and culminating in premature death. This paper concludes with some proposals for serious research after addressing some of the fallacies in Hancock’s current approach.

We have been here before. In 2003, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) used a study by the Centre for Social Marketing to attribute childhood obesity to advertising. The research was deeply flawed. Some authors have claimed that the number of TV ads watched resulted in, or at least was correlated with, childhood obesity. They deduced the number of ads from time watching TV without distinguishing the BBC from commercial channels. They overlooked the reality that the number of ads seen correlates with the percentage of time children spend watching TV. Couch potatoes get fat. Amazing. Gaming rather than playing with friends outdoors will have the same result.

There is no doubt that the growth in obesity is a problem. The Nuffield Trust reported an increase from 15% in 1993 to 28% in 2018. Addressing only calorie intake whilst ignoring calorie usage, through exercise and other means, gives a distorted picture. My golf club used to host schools. Playing golf gave the children fresh air, exercise and an introduction to a healthy lifetime. But the teachers could not cope with the risk assessment form-filling and the activity ended. Of course golf is a dangerous game. One of our members, this very week, dropped dead on the course; he was only 93.

The government’s latest proposal to ban junk (or unhealthy) food is based on two OFCOM studies and on a 2006 paper by the same team that conducted the FSA study, this time for the World Health Organisation [2] Professor Hastings’ team, now called the Institute for Social Marketing, exhibits the same biases and flawed logic as their 2003 study. The OFCOM studies deal with the time children spend looking at TV and technological gadgetry, but mentions neither advertising nor junk food.

Hancock’s main justification is public support: “Further advertising restrictions are widely supported by the public, with polling from 2019 showing that 72% of public support a 9pm watershed on junk food adverts during popular family TV shows and that 70% support a 9pm watershed online.” But that probably only reflects the long-running propaganda campaign against junk foods rather than scientific analysis. We would all rather blame others for our waist management problems than ourselves. Hancock also says it is now top of his agenda because obesity is responsible for disproportionate Covid deaths. He seems to have forgotten we will all be vaccinated in a few months time.

The government defines unhealthy food as foods and drinks which are high in fat, salt and/or sugar. From an obesity perspective, they mean fat and sugar. Excess weight is caused by too many calories in compared to calories usage. It is not just exercise; Edwardian houses had no central heating which allowed most people to eat and drink more than we do but stay slim.

In fact, “junk” or “unhealthy” foods are merely those of which government disapproves. Cornflakes and sugar are both healthy but when manufacturers combine them for our convenience, they suddenly become unhealthy. Calories are calories; it is ridiculous to suggest that a hamburger lovingly prepared by Mum is healthy whereas one with identical ingredients prepared by the evil Mr McDonald is unhealthy. Fruit juices (healthy) and coca cola (unhealthy) had about the same levels of sugar when comparisons were made in 2014 and more now that government has pushed down sugar levels in fizzy drinks.

The government focuses, reasonably enough, on digital advertising as online is disproportionately watched by younger people. Its shocking statistic that food and drink digital advertising rose by 450% between 2010 and 2017 is not quite so shocking when one takes into account the squeeze the government put on non-digital advertising for these categories, which caused advertisers to transfer, and the increase in the whole online advertising market by 275% over the same period. The comparison may not be exact as the government provides no source for its statistic.

To return to the central issue, obesity is a serious problem which needs serious research, not Hancock’s facile parade of the usual suspects. For a start, obesity needs to be understood and addressed as a social problem. For example, a Scottish study showed that “65% [of children from less affluent families were] more likely to be overweight as judged by BMI. However, these children weighed the same as more affluent children of the same age, but were 1.26 cm shorter.” Why is it that the proportion of overweight children aged 10-11 has changed very little in the 13 years to 2019 (+6%), meaning that the problem is developing thereafter? From the same report, the most deprived children are more than twice as likely (27% vs 13%) to be obese. Why is this and what can be done about it?

A cohort of teenagers should be studied over ten years to understand the behavioural, genetic and social differences between those who do and do not control their weight. Why do some obese people lose weight in response to prompts and others do not? What kind of prompts work and which do not?

Such research should be commissioned from accredited scientists, not “social marketers” with axes to grind.

[1] Tim Ambler, (2004), "Do we really want to be ruled by fatheads?", Young Consumers, Vol. 5 Iss 2 pp. 25 - 28

[2] Hastings G et al. (2006). The Extent, Nature and Effects of Food Promotion to Children: A Review of the Evidence. Geneva, World Health Organization.

Mercatus Centre: Removing Barriers to US-UK Agricultural Trade

Agriculture is far from the largest sector of trade between the United States and the United Kingdom, but it remains one of the more contentious issues in negotiating a US-UK free trade agreement. Nevertheless, agriculture offers the two nations an opportunity to liberalize trade for the benefit of consumers and producers on both sides of the Atlantic.

Negotiations toward a US-UK free trade agreement were formally launched in May 2020 and are expected to continue into 2021. With its scheduled January 2021 departure from the European Union Customs Union looming, the United Kingdom is entering a pivotal moment in its journey to establish independent trading relationships with the rest of the world. Finalizing a free trade agreement with the United States resolving agricultural issues would represent a significant step toward that goal.

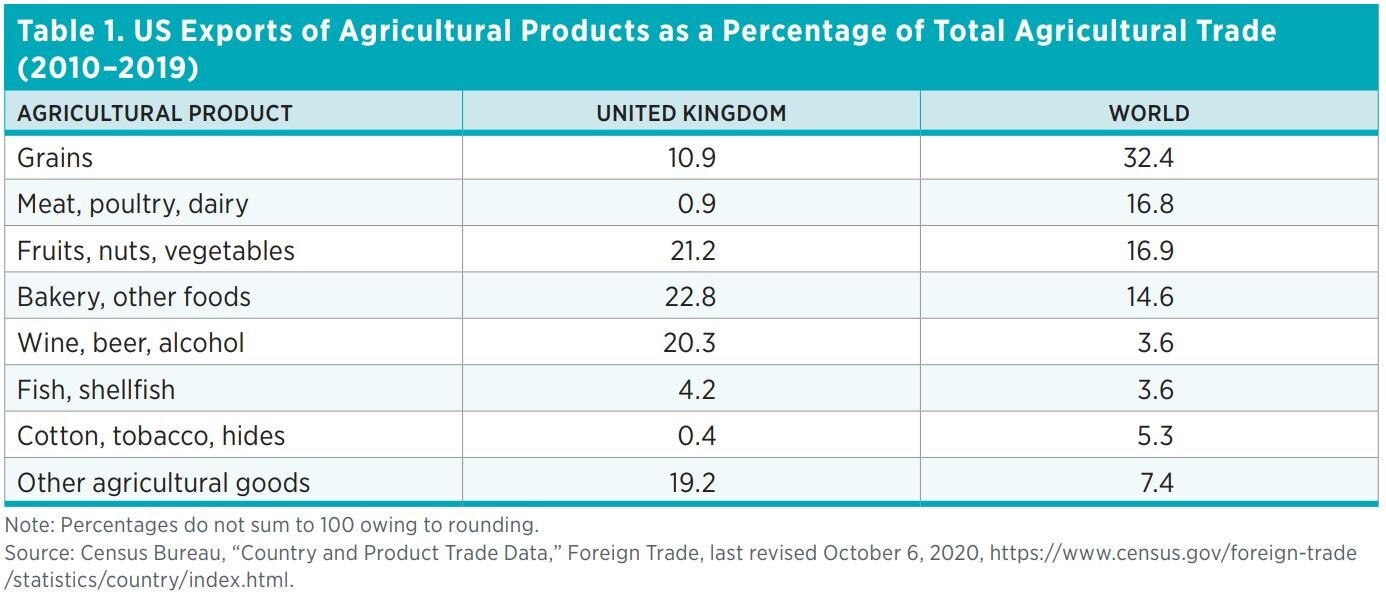

The United States and the United Kingdom already engage in a substantial amount of two-way trade in agricultural products. In 2019, US producers exported $1.93 billion worth of agricultural products to the United Kingdom. Among the top categories of exports were wine, beer, and related products ($268 million), nuts ($236 million), alcoholic beverages excluding wine and beer ($124 million), and vegetables ($117 million). That same year, Americans imported $2.89 billion worth of agricultural products from the United Kingdom, with alcoholic beverages excluding wine and beer (mostly Scotch Whiskey) accounting for $2.07 billion. Other major categories of imports included fish and shellfish ($169 million) and bakery products ($132 million). See table 1 for a breakdown of two-way trade in agricultural products.

Whereas the United Kingdom is one of the top overall trading partners of the United States, evidence suggests that agricultural trade is underdeveloped because of government-imposed barriers. In US trade with the rest of the world, exports of agricultural products in 2019 accounted for 9.1 percent of total goods exports. By comparison, farm exports accounted for only 2.8 percent of total US goods exports to the United Kingdom. The disproportionately small amount of agricultural exports to the United Kingdom is even more apparent in such categories as meat, poultry, and dairy, which accounts for 16.8 percent of total US farm exports to the rest of the world but only 0.9 percent of US farm exports to the United Kingdom. See figure 1 for a breakdown of US agricultural goods exported to the United Kingdom and a breakdown of US agricultural goods exported globally.

Agricultural Tariffs Remain Stubbornly High

The primary reason agricultural trade between the United States and the United Kingdom has been low compared with other sectors and other nations is rooted in remaining trade barriers, both tariff and nontariff barriers. Despite a general decrease in manufacturing tariffs in recent decades, tariffs on agricultural products remain stubbornly high on both sides of the Atlantic. According to the World Trade Organization, the United States applies an average weighted tariff rate of 4.6 percent against agricultural imports, and the European Union applies a 9.2 percent tariff on its agricultural imports. The highest US tariffs fall on dairy products (19 percent) and sugar and confectionary products (14.9 percent), and the highest EU tariffs apply to dairy products (37 percent), sugar and confectionery products (24.5 percent), and animal products (16 percent).

After departing the European Union Customs Union on January 1, 2021, the United Kingdom will impose its own schedule of duties called the UK Global Tariff. The UK Global Tariff reduces or eliminates tariffs on a range of items, increasing the proportion of product categories that may enter the United Kingdom duty-free from 27 percent under the European Union’s common tariff to 47 percent. The UK government has decided to retain 5,000 tariff lines, including most agricultural tariffs. On dairy products, for example, the UK Global Tariff will replace the European Union’s protectionist Meursing code with a simplified but still significant list of tariffs. As the UK Secretary of State for International Trade Elizabeth Truss explained in a May 2020 paper introducing the UK Global Tariff, the farm tariffs “have been largely retained with the aim of maintaining similar current consumption and production patterns and avoiding additional disruption for UK farmers and consumers.”

To fully exploit the unique opportunity to liberalize trade between the two nations, a US-UK free trade agreement should commit both nations to the full elimination of all tariffs, including tariffs on agricultural products. It should not be the purpose of the tariff code in either nation to preserve current consumption and production patterns; instead, trade should be liberalized so that consumers in both nations can enjoy lower prices, more variety, and better quality in foods and beverages.

Reform Food Regulations to Protect Health, Not Domestic Producers

Along with tariffs, nontariff regulatory restrictions also suppress two-way trade in farm goods, although the stated purpose of such restrictions often has nothing to do with agricultural issues. As a member of the European Union, the United Kingdom imposed a number of regulations in the name of public health and safety that have historically prevented American agricultural products from entering the UK market.

The European Commission has long supported the restriction of US agricultural goods on the basis of the precautionary principle. Enshrined in Article 191(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the precautionary principle is a core component of EU environmental law and raises barriers to external goods that the European Union deems to have “uncertain risks” for the environment. Agricultural goods that have been restricted from UK markets on the basis of the precautionary principle include the controversial chlorine-washed poultry, genetically modified crops, and hormone-induced beef. US trade negotiators have rightly complained that such a regulatory approach ignores globally accepted trade rules as well as the preponderance of scientific evidence that such practices pose no threat to public health.

The issue is not about whether the United States has lower food safety standards than the United Kingdom, but whether it has different standards that are just as effective in protecting public health and food safety. According to the Global Food Security Index, the United States has the fourth-highest food quality and safety standards in the world, significantly higher than many EU member states. In fact, it isn’t just the US Department of Agriculture and the FDA that approve the process of pathogen reduction treatment (PRT)—even the European Food Safety Authority acknowledged in a study from 2005 that “treatment with trisodium phosphate, acidified sodium chlorite, chlorine dioxide, or peroxyacid solutions, under the described conditions of use, would be of no safety concern.” In practice, washing chicken carcasses in chlorine and other PRT chemicals has proven to be more effective than alternatives in reducing the danger of salmonella poisoning in humans. What’s more, recent evidence suggests that animal welfare in production and processing standards are roughly the same in both countries when considering average and permitted densities.

In recent months, negotiators for both the United States and the United Kingdom have signaled their desire to lower agricultural trade barriers. These developments haven’t been limited to words; each side has also demonstrated political commitment to trade liberalization. After more than 20 years of banning British beef from US markets, the first shipments of beef departed the United Kingdom for the United States on September 30, 2020, marking a historic moment for UK farmers and food producers. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, long a vocal critic of anti-genetic-modification rules, stated in his first speech as prime minister, “Let’s start now to liberate the UK’s extraordinary bioscience sector from anti-genetic modification rules and let’s develop the blight-resistant crops that will feed the world.” US negotiators should work with their UK counterparts to ensure market access for US-grown genetically modified products.

Regulatory Equivalence: A mutually Beneficial Path Forward

In the ongoing negotiations, the US and UK trade negotiators should build upon such common ground to embrace an internationally accepted approach to risk assessment, particularly regarding sanitary and phytosanitary measures, as laid out by the Office of the US Trade Representative in its 2019 negotiating objectives. In attempting to address the issue, the British government has reportedly considered imposing a “dual” or “conditional” tariff system, whereby imports would only qualify for lower tariffs if they meet certain standards. However, the imposition of a dual tariff system would be rightly viewed as a protectionist trade measure. Instead, both sides should adopt a cooperative approach to establishing regulatory equivalence through consultation and multinational agreements.

There is already broad equivalence in high standards of safety, quality, and animal welfare conditions, and the two negotiating countries should look to advance approaches for establishing equivalence of existing regulations in both jurisdictions. The key objectives of trade negotiations should be removing tariff and nontariff barriers and increasing market access for the mutual benefit of all involved.

Similar tariff and regulatory issues that are on the table in the US-UK negotiations have been successfully addressed in existing free trade agreements between the United States and such trading partners as Australia, Canada, and South Korea. Each of those agreements eliminated most if not all agricultural tariffs while committing each party to address only genuine health and safety concerns through its regulations.

In the US-South Korea agreement, for example, tariffs fell to zero either immediately or after a phase-in period for corn, pork, nuts, beef, and poultry. As a result of the tariff reductions and fine tuning of regulations, US producers exported $2.50 billion in meat and poultry to South Korea in 2019, compared to a paltry $7.64 million to the United Kingdom, and $302 million in dairy products and eggs, compared to $10.3 million to the United Kingdom. In total, South Korea imported more than four times the value of US farm products ($8.13 billion) in 2019 than the United Kingdom ($1.93 billion), even though South Korea’s population, economy, and total trade with the United States are smaller than the United Kingdom’s.

An ambitious and comprehensive free trade agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom would unleash trade in agricultural products. The net welfare gain for both countries would be positive and significant; the major beneficiaries of a free trade agreement between the two nations would likely be UK consumers, through lower prices, and US producers, through increased agricultural exports.

Daniel Griswold is a Senior Research Fellow and Jack Salmon is a Research Assistant at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University

This post is a policy briefing originally published by the Mercatus Centre at George Mason University , the PDF can also be downloaded.

On the subject of a wealth tax

A committee has just recommended a wealth tax:

Family homes and pension pots would be clobbered by a proposed £260bn one-off wealth levy to pay for coronavirus, in what would amount to one of the biggest tax grabs of all time.

All British residents with personal wealth of more than £500,000 would pay a one-time 1pc tax spread over five years, under proposals from the Wealth Tax Commission, an influential group of think tanks and academics. It would hit close to one fifth of the adult population – almost 10 million people.

It’s worth noting that the modal family hit by this will be a public sector worker living in their own home in the SE of England. Because they are suggesting the taxation of housing equity and pensions. Public sector pensions, being defined benefits ones often enough, have significant value. So, clearly, do houses in the SE and London. Therefore that’s who will pay this tax. Two doctors living in Pinner might be the archetype of who will pay this tax.

It’s possible to think that that’s not quite the plutocratic running dogs that most normally think of when they consider who is wealthy.

It’s also true that wealth taxes are contraindicated under any system of sensible taxation, as Sir James Mirrlees pointed out - and gained the Nobel for.

This is a suggestion to the Treasury Committee and one of us gave evidence in the session specifically considering the idea:

I am unconvinced by this argument that we need to be raising taxes. Yes, we have just spent an enormous amount of money on dealing with the coronavirus. Depending on how we unwind or do not unwind QE, we may or may not need more tax revenue in the future. Once the vaccine is around and the economy has returned to normal, I do not see the case for higher taxation and more Government spending because the problem will be behind us. I am not buying that first stage of the argument here that we need to have more taxes.

The other thing that has just struck me is that people are talking about retrospective one-off wealth taxes. One-off wealth taxes are not all that good an idea simply because, once it has happened once, absolutely nobody is ever going to believe that it will not be done again. That is just the way people react to Government doing things. Currently, if the Chancellor stands up and says, “I am raising income tax,” then everybody has a choice to say they are going to go to work or they are not going to go to work, that they agree to pay that tax or they do not agree to pay that tax.

A retroactive tax is an appalling idea. It is akin to theft. Roy Jenkins did this in the 1960s. He retroactively imposed a 130% tax at the top end of capital incomes on the previous tax year that was already closed. That is just appalling behaviour. However much Government need the money, that is just not what we should be doing. Tax, just like any other form of law, should be, “It starts today. If you do not agree with it, you can change your behaviour in the future to avoid it and not do the activity, whatever.”

I regard taxing people today on what they did last year, changing the law on them, as an appalling breach of civil rights.

We stand by that. It’s a vile idea as well as merely being a bad one.

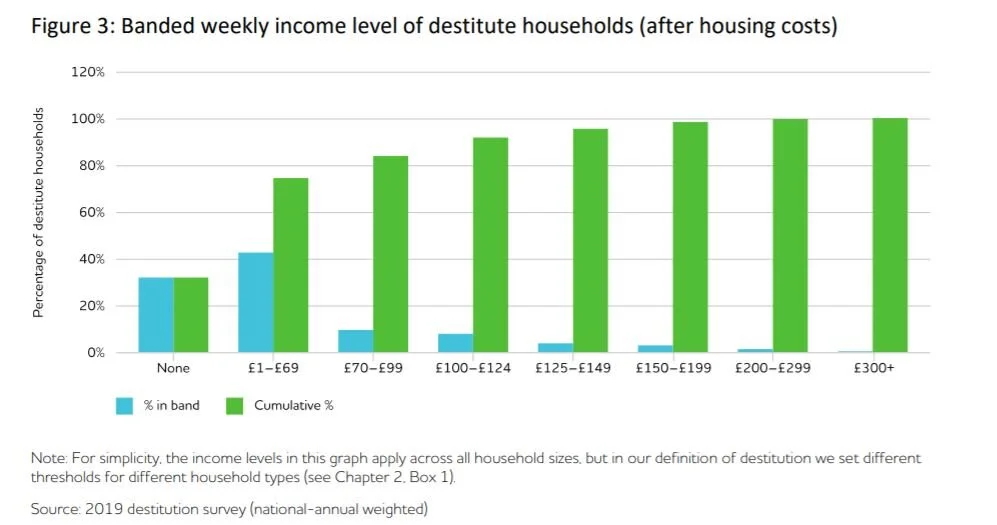

Welcome to the linguistic inflation of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has a report out talking about destitution in the UK. This rather surprises us as Barbara Castle proclaimed destitution entirely conquered in the UK all the way back in 1959. Presumably they’re talking about something else then and yes, indeed they are.

The definition of destitute is:

Box 1: Definition of destitution

People are destitute if:

EITHER:

(a) They have lacked two or more of the following six essential items over the past month, because they cannot afford them:

• shelter (they have slept rough for one or more nights)

• food (they have had fewer than two meals a day for two or more days)

• heating their home (they have been unable to heat their home for five or more days)

• lighting their home (they have been unable to light their home for five or more days)

• clothing and footwear (appropriate for the weather)

• basic toiletries (such as soap, shampoo, toothpaste and a toothbrush).

To check that the reason for going without these essential items was that they could not afford them,

We: asked respondents if this was the reason; checked that their income was below the standard relative poverty line (that is, 60% of median income – after housing costs – for the relevant household size); and checked that they had no or negligible savings.

OR:

(b) Their income is so extremely low that they are unable to purchase these essentials for themselves

We’d not try to argue that any of those things is a desirable state of affairs. But there are certain holes in the argument. The most obvious is to ask why they cannot be afforded - that is, where is the household budget going if not on those things? No, this is not to argue that the poor spend their incomes upon trivia rather than essentials. It is though to point out that budget allocations are not, for all people, optimal by these standards being given.

We have a much larger problem with this definition. Note that second definition. If someone is given these things then they are still destitute. Think through that for a moment.

As a society we insist that no one should be denied medical treatment on the basis of income. OK. We supply it - rightly or not - through the NHS. But if our list of absences that cause destitution included medical care, which a complete one should probably do, we’d thus say that people are destitute despite the existence of the NHS. Because they couldn’t afford to buy it even as they get given it. The same would be true of education (the state school system, to the extent that provides an education), libraries, even, to be ridiculous, free opera. Or, say, free shelter leaves you still destitute because you cannot afford to pay for it out of your income. Possibly even the free food and maybe toiletries from food banks leaves you still destitute.

The definition insists that either you have these things, or can pay for them that is. When what is actually desired is people having them - the definition specifically excludes people gaining them without paying for them. Charitable sourcing, that is, leaves people still in destitution as defined. Which isn’t, we insist, a useful definition of anything. It is solving that matters, not the method.

What is actually happening here is what has been happening with the definition of poverty itself over the past few decades. Linguistic inflation that is. It used to be that poverty was as Barbara Castle knew it. Now that has been conquered it has been redefined as less than 60% of median household income. Because what use campaigns against actual poverty if it no longer exists? What justification for the expropriation of the capitalist class if it is that very capitalism and markets that have abolished actual poverty? Quick, redefine so that the campaigns can continue, the justification still be advanced.

Which is what is happening here with the word destitution. Given that, in any classical sense, it no longer exists in the UK it is necessary to redefine it in order to give a justification for continuing to campaign against the system that abolished it.

Finally, a little perspective upon matters poverty. The global median household income is around - roughly you understand - £5,500 a year. That’s before housing costs. That’s also PPP adjusted, meaning that we have already taken account of the manner in which prices vary across geography. The JRF’s number is after housing costs and includes those on £5,500 a year as being destitute. It’s fair to suggest that housing costs in the UK will be £5,000 or thereabouts a year for a household, even in the best subsidised social of council housing.

So, the JRF is claiming that a household on twice global median income (housing paid plus that £5,500 a year) is in destitution. Twice global median income plus the value of the NHS, state schools, all state provided goods and services in fact, plus anything that might come their way from charitable enterprises. This isn’t even a useful definition of poverty let alone destitution.

Actually, we’d call it a perversion of the language more than anything else. But then that’s how politics works….

A truly absurd argument

Among economists, as we might have mentioned, there’s an insistence that expressed preferences - what people say - are not as useful in divination of desires as revealed preferences - what people do. The point being obvious in daily life and language, actions speak louder than words. The economist takes it a little further, insisting that it’s only when people pay the price of what it is they say they desire, pay by actually bearing that cost, that we find out whether they really do so desire.

At which point we get this sort of nonsense in response:

It warned that an exodus from traditional TV towards American streaming services meant only 38pc of 16 to 34-year-olds watched traditional broadcast content last year.

To safeguard the future of British TV, Ofcom is urging ministers to introduce new laws to hand public service broadcasters top billing on the streaming menus of smart TVs and connected devices.

Ofcom chief executive Melanie Dawes said Britain's traditional broadcasters were "among the finest in the world" but they were facing a "blizzard of change and innovation" as audiences switch to "online services with bigger budgets".

"For everything we’ve gained, we risk losing the kind of outstanding UK content that people really value," she added.

The price to be paid here is simply the time spent watching. That time, presumably, being the same for either version of TV, that home grown loveliness or that irritating colonial import. The concern here is that people preferentially watch the imports. While the claim is also made that people really value the lovely local product.

It is not possible for both of these to be true. Reality is the very thing being complained about. That people preferentially watch the foreign muck. As they do so they therefore do not value the local. At which point there’s nothing that needs to be done, is there?

We have preferences being revealed in an entirely open and free market. Why on earth would we want to change anything?

Taxpayer Value

Gordon Brown, Chancellor and then Prime Minister, made much political capital from labelling all his government’s expenditure “investment” (good, no matter how wasteful and transient), and all opposition proposals for savings “Tory cuts” (bad, no matter how sensible or good for the taxpayer).

Unfortunately, Boris Johnson is starting to misuse our language in the same way: the £30 billion defence expenditure announced last month was labelled “investment”. Some of it may be; but the 10,000 extra jobs, hopefully in the armed forces rather than the ministry, are definitely not. Investment means money spent today for benefits in future years; accountants put it in the balance sheet. Otherwise, it is current expenditure, like wages and travelling costs; accountants put that in the profit and loss, or income and expenditure, account.

Politicians would like us to believe that all their investments of our money are good, i.e. will provide a generous return in due course. Yet many such investments, from the ground nuts scheme to HS2, have been dreadful because the costs wildly exceeded those initially announced. The next government (or two) face the criticism when that reality dawns. By then, the projects are too advanced to stop.

The Private Finance Initiative

1992 saw a further muddying of the water with John Major’s creation of PFI, the Private Finance Initiative. This got around Treasury objections to government expenditure on schools, hospitals and such like by using private sector finance to build them on the never-never. Needless to say, these schemes cost a great deal more than if the Treasury had picked up the bill in the first place. The idea was that the private sector would secure so much better deals than unworldly civil servants, and those savings would outweigh the no-risk profits to the investors. If the investors had been undertaking these projects for themselves, maybe they would have found the savings; but they were spending other people’s money. The Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital is one example: “The private finance initiative (PFI) deal used to build the hospital in 2001 costs around £20m a year, which chief executive Mark Davies previously said left the hospital hamstrung.”

For over 20 years, government departments had no choice but to pay for these projects on the never-never because the Treasury claimed it had no money. But as the Covid pandemic has demonstrated, the Treasury has any amount of moolah when it wishes. According to the National Audit Office (NAO), by 2018 PFI projects to date had a capital value of around £60 billion but they cost £199 billion. The NAO ducked the question of value for money on the grounds that “there is still a lack of data available on the benefits of private finance procurement.” (p.5) The “benefits” are clear enough: the same public assets cost the taxpayer £139 billion due to government incompetence. Ex-investment banker Rishi Sunak knows enough to stop that nonsense.

Parliament must take the rap for this. Three percent of MPs are accountants compared with 11% lawyers, albeit down from the 15% in the 1970s. But you do not have to be a qualified accountant to assess the likely costs and benefits from alternative capital expenditures even if they cannot all be quantified financially. Every new regulation is supposed to include them on the impact assessment and that is all taxpayer value is.

Funding allocation

It is much easier for current expenditure. The Arts Council England is a mechanism for allocating the expenditure that (mostly) the Treasury and the Lottery provide to subsidise selected English theatres, galleries and other arts centres – about £500m in total. The Arts Council England bureaucracy helps itself to about £38m (2019/20 annual accounts, note 4c) and passes on what is left. Obviously, some administration and audit are needed but perhaps £8m rather than £38m. Oliver Dowden should ensure that the Arts Council England becomes simply a money channel to give maximum value for the taxpayer while retaining the minimum to fund an efficient allocation process.

Four government departments are essentially also money channels: apart from setting policy and monitoring progress, they contribute little to government beyond sharing out the available funding to the units down the line. They are the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (e.g. the arts and sports councils), the Department for Education (local authorities’ schools and child care), the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (local authorities) and, arguably, the Ministry of Defence (where the present central procurement system is alleged to cost the taxpayer a great deal more than the armed services themselves would pay on the open market).

Other departments are a mix of two roles — money channel and governing e.g. the Department of Health and Social Care, Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, the Home Office and Foreign Office (overseas aid). At Health, Matt Hancock has, this summer, been looking at the excess bureaucracy problem.

The higher education example

Some of the money channel thinking applies to universities. Strangely, it is not the Department for Education that devises the policy for this but Alok Sharma’s Business Department, except when it actually is under the DfE. University funding goes through several teaching and research channels when one should suffice.

Further education does, however, come under the DfE and also has half a dozen different funding channels. University Technical Colleges, presumably on the grounds that they have nothing to do with business or industrial strategy, come under the DfE. Unsurprisingly, with no focus on taxpayer value, all but two (of the 58 set up since 2010) have ranged from adequate to disaster.

The government’s whole approach to young people needs to be rationalised from a taxpayer value point of view with the channelling of funds streamlined under the Education Secretary, currently Gavin Williamson.

Conclusion

In essence, the front line of public services (doctors, nurses, police, theatres, armed forces) is the source of value for the taxpayer. Administering the front line and taking care of the money is necessary but does not directly benefit the taxpayer. Government itself is not a public service although someone has to pay for it. So, from the taxpayer’s point of view, value is maximised when the front line delivers what the taxpayer wants and the other Whitehall costs are minimised. Let us focus on achieving that.

Try out that socialist planning with Nick Timothy

Nick Timothy used to be something or other in British politics. Examining this proposal aids in telling us what has gone wrong in that sphere:

In leaving the EU, we are swapping scale for agility and uniformity for diversity and innovation. But how can we turn these principles into policies and reality?

One way is to become a first-mover and world leader in the regulation of new and high-growth industries. While the EU tends to move slowly on questions of regulation, and its decisions often reflect the interests of established firms, Britain can be faster out of the blocks. On artificial intelligence, automated vehicles, life sciences and many other sectors of the future, Britain can develop a new, more agile model of regulation, and attract investment and global expertise by getting in ahead of cumbersome competitors, like the EU, and reluctant regulators, like the United States.

At heart that claim is that those innovating, us consumers out here who want to be innovated to, need that guiding hand of the clever people in government in working out what can be done and what we want to have done. Only that - dead - hand of the State can possibly lead to the nirvana of shiny white hot heat of the new technology.

This is, writ small and yet equally damagingly, the socialist planning delusion.

The entire point of technological advance is that such expands the universe of things that can potentially be done. This then needs to be matched up against the list of things that the people - that’s you and me out here - desire to have done. Things that are successful are those things that can be newly done and also we desire to be done. The important point to note about which is that no one, no one at all, has any idea what those things are before they are tried, offered, and succeed or don’t.

How can we have regulation therefore? Other than the basics of a common system - which we might as well call Common Law - encoding things like don’t poison the customers, don’t steal and so on.

We have a theory - a surmise perhaps - about why so much of the innovation of the past couple of decades has been in that digital world. Yes, certainly, partly because that’s where the new tech is. But rather more because that’s where there hasn’t been any regulation. 25 years ago there were no - none, zip, nada - regulations or even legal guidances about how a search engine could or should work. As no one had heard of social networks the limitations upon experiment were non-existent. How one might use mobile phones was entirely unguided - which led to that canonical case of the sardine fishermen off Kerala producing pure and exultant economic growth through their employment.

Much of the rest of life, things being done more or less badly by current technology, is indeed regulated. Which is why there’s been so little innovation there, the cost of overcoming the extant regulations. In theory, at least, current law states that to make apricot marmalade one must get Parliament to change the law to allow the making of apricot marmalade. No, really, the Jams, Jellies and Marmalades regs state that citrus extracts - the essential difference between jam and marmalade - may only be added to compotes made of citrus fruits. As apricots aren’t then you can’t. £5,000 fine and or 6 months pokey if you do. It’s as if we still had to gain an individual bill through Parliament in order to gain a divorce. Something which would, we all agree, rather reduce the number that happened. So with innovation.

The case study here would be Uber and Lyft and the like. The new technology made possible a new way of hailing a cab. The extant regulation of the cab hailing business meant that tens of billions of capital needed to be expended on, umm, a new and exciting method of hailing a cab. Their strategy - expressly so - being to move into a market in such size and at such speed that the previous protective regulation be entirely overwhelmed. That is, if they’d had to go and ask for permission, for a variance in said regulation, it wouldn’t have happened at all.

This entire idea that there should be a regulatory pathway to innovation is to entirely misunderstand the principle of the issue under discussion. It’s to commit that socialist planning delusion. You know, the one that enabled the Soviet Union, according to Paul Krugman, not to increase total factor productivity one whit nor iota in its entire 7 decades of existence.

We have learnt the lesson of 1989 around here. That Nick Timothy and others presuming to rule us as yet have not is one of the things wrong with the place. Innovation needs freedom to succeed, not regulation and guidance from the political caste.

It's not up to shareholders to make companies behave morally

Mark Carney quotes Adam Smith and of course everyone claims him for their own version of reality. Philliip Inman in The Observer:

This amounts to just another form of self regulation, which cannot succeed when companies, under pressure to drive up profits, would be taking actions that increase their costs. Only cross-party, popular action, forcing governments to impose rules on corporate behaviour, can inject some morality where so little manifestly exists.

Matthew Syed also slightly misses the point:

This is why it can be argued that the problem we have in the West today isn’t capitalism per se; it is the way that giant corporations have sought to rig markets in their favour. They have been assisted by a group of economists who, in the 1970s, started to say some truly bizarre things. That markets don’t need regulation. That government is bad. That companies have no responsibility to society, but only to their owners. In effect, they sought to denigrate the values that markets had cultivated, insinuating that sectional interests alone should prevail.

Given that we are on the extreme bleeding edge of those being criticised here it’s worth our pointing out that no one at all believes that markets require no regulation. The discussion is about who does that regulating.

Some regulation does indeed need to be at the level of government - to pick an extreme example who may own a nuclear bomb, say. But the ethics and morality of business, that’s best done by consumers. On the entirely logical grounds that there are many different ethical and moral systems, many of which conflict. Therefore it’s necessary to allow the adherents of each to deploy their own - subject to the usual third party harm restrictions - as they wish.

So, if you prefer your soya fed chicken to not have a link with farming Brazil’s Cerrado then that is available. As is organic, free range, and factory farmed, chlorine washed and Cerrado stuffed. Your morals and you impose them upon suppliers by making a conscious choice.

Not making a choice on such grounds is rather evidence that you don’t care enough about the ethics to bother. Something which isn’t a great argument in favour of getting government to force you.

The ethical and moral monitors of corporate behaviour are us, as consumers.

Those who would rule us think differently of course. Allowing us to do our own thing rather takes the fun out of ruling. Further, we might make the wrong choices, impose the wrong moral values. This summer, for example, there was a rag trade company accused of using subcontractors in Leicester that paid below minimum wage. The share price dropped precipitately as worries about the consumer reaction spread. A few weeks later it became apparent that the teenage customers for the schmutter didn’t care and had carried on buying - the share price revived.

The consumers had shown they didn’t care about the allegations. That is, for them this was not a moral nor ethical issue. Well, that’s how society is supposed to work. We’re all free to live our lives as we wish, inside whatever moral and ethical constraints we wish to impose upon ourselves.

The opposition to this consumer regulation comes from those who would impose, upon others, their own ethical strictures. And that’s not really moral, is it?

Shareholder primacy is regulated by consumer supremacy and that’s, barring those extreme cases of things that go bang, the way to do it.

Of course interest rates can go below zero

That something can be done is of course not quite the same as the statement that this thing should be done.

UK interest rates can be cut below zero if needed to ward off the scars of Covid-19 or an economic hit from a no-deal Brexit, the Bank of England's Michael Saunders has said.

Rates are currently at a record low of 0.1pc but the Bank has embarked on an review of negative rates in the event the Monetary Policy Committee decides to go further still.

MPC member Michael Saunders said his own view was that the lower bound for interest rates was "probably a little below zero"

We agree with the “can”. The lower bound isn’t that zero - we can see that as there are negative rates out there already, both nominal and real - which leads to the question, well, what is the lower bound?

The answer coming from considering alternatives, substitution. At some point having money in the bank - at some negative interest rate that is - becomes more expensive than not having money in the bank. Or, given financial markets, having the money not in some bond or repo instrument or whatever. As Tyler Cowen pointed out many years ago this is really constrained by the cost of holding cash in a vault. That might be half a percent, one, possibly even two but it does exist as that constraint.

If you’d lose 10% a year from having money in the banking system then having it not in it at a cost of 2% is an obvious thing to do. Move those numbers around as you wish to find that actual lower interest rate bound.

Below zero interest rates can be had, certainly, but not all that far below zero. Whether it should be done is another matter of course. Our suspicion is that even trying it would lead to our needing a radical change to pension funding arrangements. Imagine the capital required now to fund a pension payable in 50 years’ time in a negative interest rate world. Near none of those organisations still running defined benefit pensions would survive - and we really, really, should account for civil service and governmental body pensions in the same manner as well.