Just to remind, the only fair trade is free trade

Given the arguments going on about the UK’s new relationship with the European Union a little reminder to everyone - the only fair trade is free trade:

The main stumbling block is measures to ensure that trade is fair. If Britain and the EU are to allow unfettered access to each other’s markets, then there must be mechanisms in place to prevent undercutting – whether it takes the form of a race to the bottom in stripping workers’ rights and environmental protections, or artificially lowering the costs of production with direct or indirect state subsidies.

This is to entirely miss the point. Imagine - go on, just imagine - that some people are willing to work for £100 a month to make t-shirts. Given the options available to them in the time and place they’re at this seems like a reasonable deal to them. So, given that this wage is below the minimum wage in the UK should we ban imports from them? The argument about no undercutting insists yes, we should ban.

That’s the end of third world garment production then and the return of tens of millions to penury.

If we in Britain - or them over there in the remnant EU of course - decide that we’re willing to go to work under this or that other set of rules then that’s up to us - or them.

But even that obviousness still doesn’t quite plumb the depths of the mistake being made here. For trade isn’t about access to someone else’s markets. It’s that consumers gain access to the production they desire. The argument for free trade isn’t that British cheese makers may sell in Berlin, or that German car makers may in Grimsby. It’s that Jam Donuts may buy their cheese from anyone, worldwide, so too that Codheads can drive the vehicles they desire, both free of bureaucratic restriction.

What the treaty should be is therefore obvious, as we’ve said before:

1) There will be no tariff or non-tariff barriers on imports into the UK.

2) Imports will be regulated in exactly the same manner as domestic production.

3) You can do what you like.

4) Err, that’s it.

The only fair trade is free trade.

If you start from the wrong facts you'll never reason yourself to a useful conclusion

Will Hutton tells us that:

The US and Britain in particular have created an economic system of organised plunder, resulting in widespread precarious livelihoods. Over the last generation we have witnessed the rise of rentier capitalism, supercharged by new technologies, to establish economic structures in which having and owning has been vastly privileged over doing, creating and risk-taking. The share of profits in national income has risen, the share of wages fallen while work has become organised around short-term contracts. The decline in the incentive to make and innovate has been accompanied by a weakening in the rate of productivity growth.

That doesn’t make logical sense. If the profit rate, or profit share, has risen then there will be ever more fighting among the capitalists to expropriate a greater share of that rising amount. Investment and thus productivity will soar that is.

Last week there were the first signs that change was afoot. As a last hurrah for the old order, the share price in Airbnb, a company founded on creating a digital platform on which a multitude of mini-landlords can offer stays in their home for VAT-free rents, doubled in the first day of trading.

To use Airbnb as an example of the claim is mindgarglingly stupid. Those apartments, before they were being rented out for short stays, were being either not used or used for lower valued uses. Thus the system either brings into use previously unused capital assets or moves them from lower to higher valued uses. This is a pure addition to the Solow Residual. This is unadorned economic growth and increased productivity. We have more output without having to add either more labour or more capital to the system. This is, by definition, productivity growth.

But what’s really wrong here is Hutton’s insistence that the profit share is rising. At least as far as the UK economy is concerned this isn’t true.

We've labour and capital shares. And then mixed income. This is essentially the earnings of the self-employed. We don't really know how much of this is labour income and how much capital. That self-employed roofer gets some of his income simply from his labour, but also some of it from his truck, his tools, the capital of his little business. Rather than trying to work it out we just count it as that mixed income. The final part is subsidies to production plus taxes on consumption. They're not things that either capital nor labour get so again we count them separately.

When I did look (given my technical skills, with a certain amount of help) at the UK figures the labour share had fallen, sure enough. But the capital share hadn't risen. What had risen was the mixed income share of the economy. And what had also risen was subsidies and taxes. Quite obviously, too, the VAT rate has doubled since its introduction and it now collects a considerable portion of GDP through taxation of consumption. Not quite 10% of GDP, but getting there. And subsidies have rather risen--all those feed in tariffs for renewable energy come in here.

What we found therefore was that yes, the labour share had fallen but not because the capital share had risen.

So, the facts are wrong, the observation is wrong and the logic fails anyway. This isn’t a good starting point from which to try to reach a useful conclusion. But then it is a Will Hutton column.

It's about power, it's always about power

Polly Toynbee tells us all that it’s pretty cool when rich people give away goodly portions of their wealth:

Because these are dark days in a bleak winter, Covid-stricken and Brexit-paralysed, let me introduce you to a couple who will raise your spirits. Frances Connolly and her husband, Patrick, were living in a rented terrace house in Moira, County Down when, on New Year’s Day 2019, they won the EuroMillions jackpot of £114.9m, one of the highest payouts ever. Since then they have engaged in one of the biggest lottery giveaways ever, according to Camelot, the lottery operator.

The Connollys are expending their resources in the manner they wish to. Nothing for us to complain about there. Polly does, however, have a complaint:

But as she knows, charity is not an answer to inequality. Bill Gates, Warren Buffett and George Soros do admirable good, but their philanthropy is no excuse for out-of-control mega-wealth that should be capped, taxed and spent on priorities set by democratic governments.

Polly insists that us people out here should not be allowed to dispose of our own resources as we wish. Instead, above some level of pocket money, all should be determined by the political process. You know, the one that Polly is a part of, Polly influences and the one where Polly would have power over where the money was directed.

That is, Ms. Toynbee prefers a system in which she gets to determine - in part - what happens to your property. Sure and we all desire to have power over others but it’s the duty of liberals to restrict that, not drool over such an imposition.

How fashionable opinion doth gyre and gimbal in the wind

A year ago fashionable opinion was that fast fashion is a very bad thing. We were all being ultra-consumerist by buying clothes that we wore a few times only. Why, it was almost as if the lumpenproletariat were able, like their upper bourgeoisie betters, to doll themselves up for a night out. Thus the end point of the argument, that we should all spend much more on each piece of clothing and have many fewer of them. Sumptuary laws imposed by intellectual fashion rather than the law - although you could see that argument coming down the pike too.

There was also a campaign to massively increase the wages of those in those sweatshops. That they were vastly better than any alternative available in that time and place was not an argument that made much headway. Instead factory workers should be making two and three times the median wages for those countries just because. It’s justice, innit?

Events have led to that fast fashion production line being interrupted:

In March, as the pandemic hit, the factory closed after foreign buyers pulled their business from the factory and thousands of workers lost their jobs. Last week, amid mounting desperation and despair, hundreds of them came together demanding they be paid months of outstanding wages and pension contributions, without which they say they will be unable to feed their children.

This turn in opinion at least has the benefit of being based upon truth. The absence of fast fashion does mean that some of the poorer in the world are distinctly less well off:

A year ago she was working as a machine operator at A-One (BD) Ltd and supporting her young family. Now she, along with thousands of others, is jobless and destitute.

Azad joined the protest because she didn’t know what else to do. She is the sole breadwinner for her family of six and is surviving on the charity of her neighbours.

So, what should be done about this?

Exactly what we have been saying for years. The best way to aid poor people in poor countries is by buying goods made by poor people in poor countries.

From which we can gain two policy prescriptions. The first and most obvious is that we should not charge tariffs upon our own purchases of these goods made by poor people in poor places. It’s of vastly more benefit to them that we buy than anything that is done with the official aid budget. Indeed, perhaps the best use of that aid budget would be to replace the tariff income to government that we’d not gain by declaring unilateral free trade.

The second is that all those whingeing about fast fashion can stop changing their opinions. Even if it is by chance that fashionable opinion is now that Bangladeshi workers being on the bread- and unemployment- line benefit from not being so. Thus, let us employ them and gain sparkly party clothes for ourselves by purchasing their output.

Next time you’re passing some outlet that retails sweatshop made clothes don’t just buy one, buy three. Anyone, and everyone, who wants to make Azad richer should, must, start by buying the product of her labour.

A victory for the liberal ideal at Cambridge University

Most who currently describe themselves as liberals - in that American sense becoming more common in England - will dislike this recent event. We, being actual liberals, applaud it entirely. For it the victory of the base liberal ideal:

Cambridge University dons have prevailed in a free speech row after voting down an attempt by university chiefs to force them to be “respectful of the diverse identities of others”.

The change is from “respect” to “tolerate”.

A group of academics managed to force a ballot on a series of amendments including that the phrase “respectful of” is replaced with “tolerate”.

….

The amendment proposing ‘respect’ should be replaced with ‘tolerate’ passed by 1,378 votes to 208, while the other amendments proposed by Dr Ahmed passed by 1,243 to 311 and 1,202 to 342.

A liberal polity is one in which we all get to do our own thing - absent those third party effects re noses and fist swinging - and everyone else has to put up with our doing so.

To insist that others respect our decisions - or the way we’re made - over sexuality, race, culture, preferences, utility or anything else is not to be liberal. For that is to impose upon the observer a duty which is in itself illiberal. That they have to put up with, tolerate, is the definition of that desired liberality.

After all, if we’ve got to respect someone who believes in some idiocy like Marx’s Labour Theory of Value is to place a substantial burden upon those of us who have grasped the marginalist revolution. That we’ve got to tolerate people who believe idiocies is just part of the human condition.

Obesity? Round up the usual suspects

You know the form: government sells off school playing fields, children get fat, government must be seen to do something but poor old Matt Hancock is preoccupied with Covid, so he rounds up usual suspects, namely junk food and advertising. He shows no interest in analysing the real causes of the growth of obesity nationwide, starting in childhood, continuing through life and culminating in premature death. This paper concludes with some proposals for serious research after addressing some of the fallacies in Hancock’s current approach.

We have been here before. In 2003, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) used a study by the Centre for Social Marketing to attribute childhood obesity to advertising. The research was deeply flawed. Some authors have claimed that the number of TV ads watched resulted in, or at least was correlated with, childhood obesity. They deduced the number of ads from time watching TV without distinguishing the BBC from commercial channels. They overlooked the reality that the number of ads seen correlates with the percentage of time children spend watching TV. Couch potatoes get fat. Amazing. Gaming rather than playing with friends outdoors will have the same result.

There is no doubt that the growth in obesity is a problem. The Nuffield Trust reported an increase from 15% in 1993 to 28% in 2018. Addressing only calorie intake whilst ignoring calorie usage, through exercise and other means, gives a distorted picture. My golf club used to host schools. Playing golf gave the children fresh air, exercise and an introduction to a healthy lifetime. But the teachers could not cope with the risk assessment form-filling and the activity ended. Of course golf is a dangerous game. One of our members, this very week, dropped dead on the course; he was only 93.

The government’s latest proposal to ban junk (or unhealthy) food is based on two OFCOM studies and on a 2006 paper by the same team that conducted the FSA study, this time for the World Health Organisation [2] Professor Hastings’ team, now called the Institute for Social Marketing, exhibits the same biases and flawed logic as their 2003 study. The OFCOM studies deal with the time children spend looking at TV and technological gadgetry, but mentions neither advertising nor junk food.

Hancock’s main justification is public support: “Further advertising restrictions are widely supported by the public, with polling from 2019 showing that 72% of public support a 9pm watershed on junk food adverts during popular family TV shows and that 70% support a 9pm watershed online.” But that probably only reflects the long-running propaganda campaign against junk foods rather than scientific analysis. We would all rather blame others for our waist management problems than ourselves. Hancock also says it is now top of his agenda because obesity is responsible for disproportionate Covid deaths. He seems to have forgotten we will all be vaccinated in a few months time.

The government defines unhealthy food as foods and drinks which are high in fat, salt and/or sugar. From an obesity perspective, they mean fat and sugar. Excess weight is caused by too many calories in compared to calories usage. It is not just exercise; Edwardian houses had no central heating which allowed most people to eat and drink more than we do but stay slim.

In fact, “junk” or “unhealthy” foods are merely those of which government disapproves. Cornflakes and sugar are both healthy but when manufacturers combine them for our convenience, they suddenly become unhealthy. Calories are calories; it is ridiculous to suggest that a hamburger lovingly prepared by Mum is healthy whereas one with identical ingredients prepared by the evil Mr McDonald is unhealthy. Fruit juices (healthy) and coca cola (unhealthy) had about the same levels of sugar when comparisons were made in 2014 and more now that government has pushed down sugar levels in fizzy drinks.

The government focuses, reasonably enough, on digital advertising as online is disproportionately watched by younger people. Its shocking statistic that food and drink digital advertising rose by 450% between 2010 and 2017 is not quite so shocking when one takes into account the squeeze the government put on non-digital advertising for these categories, which caused advertisers to transfer, and the increase in the whole online advertising market by 275% over the same period. The comparison may not be exact as the government provides no source for its statistic.

To return to the central issue, obesity is a serious problem which needs serious research, not Hancock’s facile parade of the usual suspects. For a start, obesity needs to be understood and addressed as a social problem. For example, a Scottish study showed that “65% [of children from less affluent families were] more likely to be overweight as judged by BMI. However, these children weighed the same as more affluent children of the same age, but were 1.26 cm shorter.” Why is it that the proportion of overweight children aged 10-11 has changed very little in the 13 years to 2019 (+6%), meaning that the problem is developing thereafter? From the same report, the most deprived children are more than twice as likely (27% vs 13%) to be obese. Why is this and what can be done about it?

A cohort of teenagers should be studied over ten years to understand the behavioural, genetic and social differences between those who do and do not control their weight. Why do some obese people lose weight in response to prompts and others do not? What kind of prompts work and which do not?

Such research should be commissioned from accredited scientists, not “social marketers” with axes to grind.

[1] Tim Ambler, (2004), "Do we really want to be ruled by fatheads?", Young Consumers, Vol. 5 Iss 2 pp. 25 - 28

[2] Hastings G et al. (2006). The Extent, Nature and Effects of Food Promotion to Children: A Review of the Evidence. Geneva, World Health Organization.

Mercatus Centre: Removing Barriers to US-UK Agricultural Trade

Agriculture is far from the largest sector of trade between the United States and the United Kingdom, but it remains one of the more contentious issues in negotiating a US-UK free trade agreement. Nevertheless, agriculture offers the two nations an opportunity to liberalize trade for the benefit of consumers and producers on both sides of the Atlantic.

Negotiations toward a US-UK free trade agreement were formally launched in May 2020 and are expected to continue into 2021. With its scheduled January 2021 departure from the European Union Customs Union looming, the United Kingdom is entering a pivotal moment in its journey to establish independent trading relationships with the rest of the world. Finalizing a free trade agreement with the United States resolving agricultural issues would represent a significant step toward that goal.

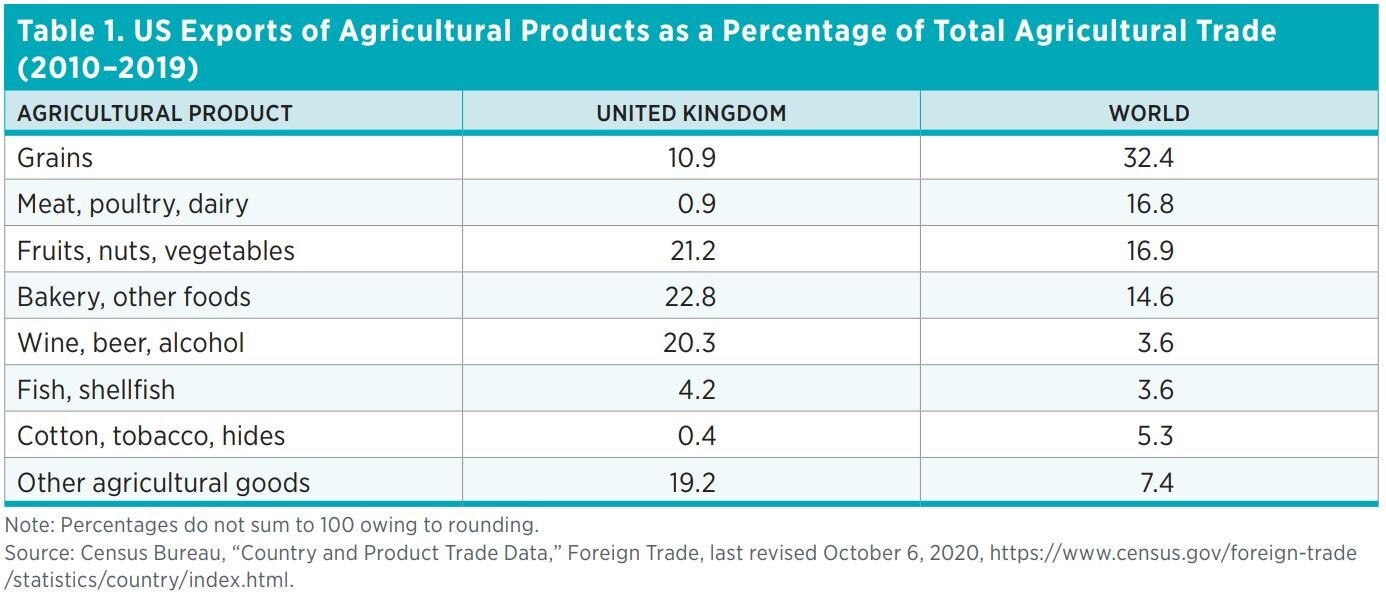

The United States and the United Kingdom already engage in a substantial amount of two-way trade in agricultural products. In 2019, US producers exported $1.93 billion worth of agricultural products to the United Kingdom. Among the top categories of exports were wine, beer, and related products ($268 million), nuts ($236 million), alcoholic beverages excluding wine and beer ($124 million), and vegetables ($117 million). That same year, Americans imported $2.89 billion worth of agricultural products from the United Kingdom, with alcoholic beverages excluding wine and beer (mostly Scotch Whiskey) accounting for $2.07 billion. Other major categories of imports included fish and shellfish ($169 million) and bakery products ($132 million). See table 1 for a breakdown of two-way trade in agricultural products.

Whereas the United Kingdom is one of the top overall trading partners of the United States, evidence suggests that agricultural trade is underdeveloped because of government-imposed barriers. In US trade with the rest of the world, exports of agricultural products in 2019 accounted for 9.1 percent of total goods exports. By comparison, farm exports accounted for only 2.8 percent of total US goods exports to the United Kingdom. The disproportionately small amount of agricultural exports to the United Kingdom is even more apparent in such categories as meat, poultry, and dairy, which accounts for 16.8 percent of total US farm exports to the rest of the world but only 0.9 percent of US farm exports to the United Kingdom. See figure 1 for a breakdown of US agricultural goods exported to the United Kingdom and a breakdown of US agricultural goods exported globally.

Agricultural Tariffs Remain Stubbornly High

The primary reason agricultural trade between the United States and the United Kingdom has been low compared with other sectors and other nations is rooted in remaining trade barriers, both tariff and nontariff barriers. Despite a general decrease in manufacturing tariffs in recent decades, tariffs on agricultural products remain stubbornly high on both sides of the Atlantic. According to the World Trade Organization, the United States applies an average weighted tariff rate of 4.6 percent against agricultural imports, and the European Union applies a 9.2 percent tariff on its agricultural imports. The highest US tariffs fall on dairy products (19 percent) and sugar and confectionary products (14.9 percent), and the highest EU tariffs apply to dairy products (37 percent), sugar and confectionery products (24.5 percent), and animal products (16 percent).

After departing the European Union Customs Union on January 1, 2021, the United Kingdom will impose its own schedule of duties called the UK Global Tariff. The UK Global Tariff reduces or eliminates tariffs on a range of items, increasing the proportion of product categories that may enter the United Kingdom duty-free from 27 percent under the European Union’s common tariff to 47 percent. The UK government has decided to retain 5,000 tariff lines, including most agricultural tariffs. On dairy products, for example, the UK Global Tariff will replace the European Union’s protectionist Meursing code with a simplified but still significant list of tariffs. As the UK Secretary of State for International Trade Elizabeth Truss explained in a May 2020 paper introducing the UK Global Tariff, the farm tariffs “have been largely retained with the aim of maintaining similar current consumption and production patterns and avoiding additional disruption for UK farmers and consumers.”

To fully exploit the unique opportunity to liberalize trade between the two nations, a US-UK free trade agreement should commit both nations to the full elimination of all tariffs, including tariffs on agricultural products. It should not be the purpose of the tariff code in either nation to preserve current consumption and production patterns; instead, trade should be liberalized so that consumers in both nations can enjoy lower prices, more variety, and better quality in foods and beverages.

Reform Food Regulations to Protect Health, Not Domestic Producers

Along with tariffs, nontariff regulatory restrictions also suppress two-way trade in farm goods, although the stated purpose of such restrictions often has nothing to do with agricultural issues. As a member of the European Union, the United Kingdom imposed a number of regulations in the name of public health and safety that have historically prevented American agricultural products from entering the UK market.

The European Commission has long supported the restriction of US agricultural goods on the basis of the precautionary principle. Enshrined in Article 191(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, the precautionary principle is a core component of EU environmental law and raises barriers to external goods that the European Union deems to have “uncertain risks” for the environment. Agricultural goods that have been restricted from UK markets on the basis of the precautionary principle include the controversial chlorine-washed poultry, genetically modified crops, and hormone-induced beef. US trade negotiators have rightly complained that such a regulatory approach ignores globally accepted trade rules as well as the preponderance of scientific evidence that such practices pose no threat to public health.

The issue is not about whether the United States has lower food safety standards than the United Kingdom, but whether it has different standards that are just as effective in protecting public health and food safety. According to the Global Food Security Index, the United States has the fourth-highest food quality and safety standards in the world, significantly higher than many EU member states. In fact, it isn’t just the US Department of Agriculture and the FDA that approve the process of pathogen reduction treatment (PRT)—even the European Food Safety Authority acknowledged in a study from 2005 that “treatment with trisodium phosphate, acidified sodium chlorite, chlorine dioxide, or peroxyacid solutions, under the described conditions of use, would be of no safety concern.” In practice, washing chicken carcasses in chlorine and other PRT chemicals has proven to be more effective than alternatives in reducing the danger of salmonella poisoning in humans. What’s more, recent evidence suggests that animal welfare in production and processing standards are roughly the same in both countries when considering average and permitted densities.

In recent months, negotiators for both the United States and the United Kingdom have signaled their desire to lower agricultural trade barriers. These developments haven’t been limited to words; each side has also demonstrated political commitment to trade liberalization. After more than 20 years of banning British beef from US markets, the first shipments of beef departed the United Kingdom for the United States on September 30, 2020, marking a historic moment for UK farmers and food producers. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, long a vocal critic of anti-genetic-modification rules, stated in his first speech as prime minister, “Let’s start now to liberate the UK’s extraordinary bioscience sector from anti-genetic modification rules and let’s develop the blight-resistant crops that will feed the world.” US negotiators should work with their UK counterparts to ensure market access for US-grown genetically modified products.

Regulatory Equivalence: A mutually Beneficial Path Forward

In the ongoing negotiations, the US and UK trade negotiators should build upon such common ground to embrace an internationally accepted approach to risk assessment, particularly regarding sanitary and phytosanitary measures, as laid out by the Office of the US Trade Representative in its 2019 negotiating objectives. In attempting to address the issue, the British government has reportedly considered imposing a “dual” or “conditional” tariff system, whereby imports would only qualify for lower tariffs if they meet certain standards. However, the imposition of a dual tariff system would be rightly viewed as a protectionist trade measure. Instead, both sides should adopt a cooperative approach to establishing regulatory equivalence through consultation and multinational agreements.

There is already broad equivalence in high standards of safety, quality, and animal welfare conditions, and the two negotiating countries should look to advance approaches for establishing equivalence of existing regulations in both jurisdictions. The key objectives of trade negotiations should be removing tariff and nontariff barriers and increasing market access for the mutual benefit of all involved.

Similar tariff and regulatory issues that are on the table in the US-UK negotiations have been successfully addressed in existing free trade agreements between the United States and such trading partners as Australia, Canada, and South Korea. Each of those agreements eliminated most if not all agricultural tariffs while committing each party to address only genuine health and safety concerns through its regulations.

In the US-South Korea agreement, for example, tariffs fell to zero either immediately or after a phase-in period for corn, pork, nuts, beef, and poultry. As a result of the tariff reductions and fine tuning of regulations, US producers exported $2.50 billion in meat and poultry to South Korea in 2019, compared to a paltry $7.64 million to the United Kingdom, and $302 million in dairy products and eggs, compared to $10.3 million to the United Kingdom. In total, South Korea imported more than four times the value of US farm products ($8.13 billion) in 2019 than the United Kingdom ($1.93 billion), even though South Korea’s population, economy, and total trade with the United States are smaller than the United Kingdom’s.

An ambitious and comprehensive free trade agreement between the United States and the United Kingdom would unleash trade in agricultural products. The net welfare gain for both countries would be positive and significant; the major beneficiaries of a free trade agreement between the two nations would likely be UK consumers, through lower prices, and US producers, through increased agricultural exports.

Daniel Griswold is a Senior Research Fellow and Jack Salmon is a Research Assistant at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University

This post is a policy briefing originally published by the Mercatus Centre at George Mason University , the PDF can also be downloaded.

On the subject of a wealth tax

A committee has just recommended a wealth tax:

Family homes and pension pots would be clobbered by a proposed £260bn one-off wealth levy to pay for coronavirus, in what would amount to one of the biggest tax grabs of all time.

All British residents with personal wealth of more than £500,000 would pay a one-time 1pc tax spread over five years, under proposals from the Wealth Tax Commission, an influential group of think tanks and academics. It would hit close to one fifth of the adult population – almost 10 million people.

It’s worth noting that the modal family hit by this will be a public sector worker living in their own home in the SE of England. Because they are suggesting the taxation of housing equity and pensions. Public sector pensions, being defined benefits ones often enough, have significant value. So, clearly, do houses in the SE and London. Therefore that’s who will pay this tax. Two doctors living in Pinner might be the archetype of who will pay this tax.

It’s possible to think that that’s not quite the plutocratic running dogs that most normally think of when they consider who is wealthy.

It’s also true that wealth taxes are contraindicated under any system of sensible taxation, as Sir James Mirrlees pointed out - and gained the Nobel for.

This is a suggestion to the Treasury Committee and one of us gave evidence in the session specifically considering the idea:

I am unconvinced by this argument that we need to be raising taxes. Yes, we have just spent an enormous amount of money on dealing with the coronavirus. Depending on how we unwind or do not unwind QE, we may or may not need more tax revenue in the future. Once the vaccine is around and the economy has returned to normal, I do not see the case for higher taxation and more Government spending because the problem will be behind us. I am not buying that first stage of the argument here that we need to have more taxes.

The other thing that has just struck me is that people are talking about retrospective one-off wealth taxes. One-off wealth taxes are not all that good an idea simply because, once it has happened once, absolutely nobody is ever going to believe that it will not be done again. That is just the way people react to Government doing things. Currently, if the Chancellor stands up and says, “I am raising income tax,” then everybody has a choice to say they are going to go to work or they are not going to go to work, that they agree to pay that tax or they do not agree to pay that tax.

A retroactive tax is an appalling idea. It is akin to theft. Roy Jenkins did this in the 1960s. He retroactively imposed a 130% tax at the top end of capital incomes on the previous tax year that was already closed. That is just appalling behaviour. However much Government need the money, that is just not what we should be doing. Tax, just like any other form of law, should be, “It starts today. If you do not agree with it, you can change your behaviour in the future to avoid it and not do the activity, whatever.”

I regard taxing people today on what they did last year, changing the law on them, as an appalling breach of civil rights.

We stand by that. It’s a vile idea as well as merely being a bad one.

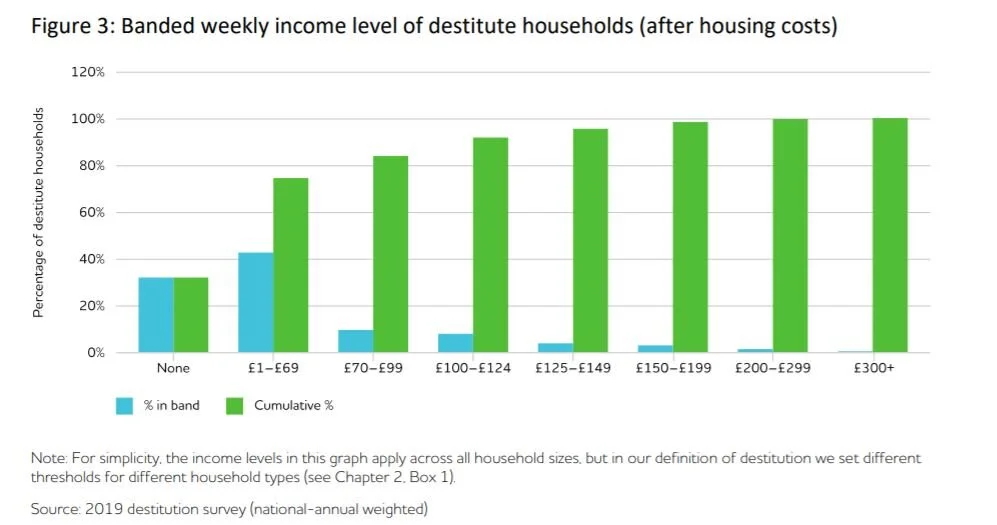

Welcome to the linguistic inflation of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has a report out talking about destitution in the UK. This rather surprises us as Barbara Castle proclaimed destitution entirely conquered in the UK all the way back in 1959. Presumably they’re talking about something else then and yes, indeed they are.

The definition of destitute is:

Box 1: Definition of destitution

People are destitute if:

EITHER:

(a) They have lacked two or more of the following six essential items over the past month, because they cannot afford them:

• shelter (they have slept rough for one or more nights)

• food (they have had fewer than two meals a day for two or more days)

• heating their home (they have been unable to heat their home for five or more days)

• lighting their home (they have been unable to light their home for five or more days)

• clothing and footwear (appropriate for the weather)

• basic toiletries (such as soap, shampoo, toothpaste and a toothbrush).

To check that the reason for going without these essential items was that they could not afford them,

We: asked respondents if this was the reason; checked that their income was below the standard relative poverty line (that is, 60% of median income – after housing costs – for the relevant household size); and checked that they had no or negligible savings.

OR:

(b) Their income is so extremely low that they are unable to purchase these essentials for themselves

We’d not try to argue that any of those things is a desirable state of affairs. But there are certain holes in the argument. The most obvious is to ask why they cannot be afforded - that is, where is the household budget going if not on those things? No, this is not to argue that the poor spend their incomes upon trivia rather than essentials. It is though to point out that budget allocations are not, for all people, optimal by these standards being given.

We have a much larger problem with this definition. Note that second definition. If someone is given these things then they are still destitute. Think through that for a moment.

As a society we insist that no one should be denied medical treatment on the basis of income. OK. We supply it - rightly or not - through the NHS. But if our list of absences that cause destitution included medical care, which a complete one should probably do, we’d thus say that people are destitute despite the existence of the NHS. Because they couldn’t afford to buy it even as they get given it. The same would be true of education (the state school system, to the extent that provides an education), libraries, even, to be ridiculous, free opera. Or, say, free shelter leaves you still destitute because you cannot afford to pay for it out of your income. Possibly even the free food and maybe toiletries from food banks leaves you still destitute.

The definition insists that either you have these things, or can pay for them that is. When what is actually desired is people having them - the definition specifically excludes people gaining them without paying for them. Charitable sourcing, that is, leaves people still in destitution as defined. Which isn’t, we insist, a useful definition of anything. It is solving that matters, not the method.

What is actually happening here is what has been happening with the definition of poverty itself over the past few decades. Linguistic inflation that is. It used to be that poverty was as Barbara Castle knew it. Now that has been conquered it has been redefined as less than 60% of median household income. Because what use campaigns against actual poverty if it no longer exists? What justification for the expropriation of the capitalist class if it is that very capitalism and markets that have abolished actual poverty? Quick, redefine so that the campaigns can continue, the justification still be advanced.

Which is what is happening here with the word destitution. Given that, in any classical sense, it no longer exists in the UK it is necessary to redefine it in order to give a justification for continuing to campaign against the system that abolished it.

Finally, a little perspective upon matters poverty. The global median household income is around - roughly you understand - £5,500 a year. That’s before housing costs. That’s also PPP adjusted, meaning that we have already taken account of the manner in which prices vary across geography. The JRF’s number is after housing costs and includes those on £5,500 a year as being destitute. It’s fair to suggest that housing costs in the UK will be £5,000 or thereabouts a year for a household, even in the best subsidised social of council housing.

So, the JRF is claiming that a household on twice global median income (housing paid plus that £5,500 a year) is in destitution. Twice global median income plus the value of the NHS, state schools, all state provided goods and services in fact, plus anything that might come their way from charitable enterprises. This isn’t even a useful definition of poverty let alone destitution.

Actually, we’d call it a perversion of the language more than anything else. But then that’s how politics works….

A truly absurd argument

Among economists, as we might have mentioned, there’s an insistence that expressed preferences - what people say - are not as useful in divination of desires as revealed preferences - what people do. The point being obvious in daily life and language, actions speak louder than words. The economist takes it a little further, insisting that it’s only when people pay the price of what it is they say they desire, pay by actually bearing that cost, that we find out whether they really do so desire.

At which point we get this sort of nonsense in response:

It warned that an exodus from traditional TV towards American streaming services meant only 38pc of 16 to 34-year-olds watched traditional broadcast content last year.

To safeguard the future of British TV, Ofcom is urging ministers to introduce new laws to hand public service broadcasters top billing on the streaming menus of smart TVs and connected devices.

Ofcom chief executive Melanie Dawes said Britain's traditional broadcasters were "among the finest in the world" but they were facing a "blizzard of change and innovation" as audiences switch to "online services with bigger budgets".

"For everything we’ve gained, we risk losing the kind of outstanding UK content that people really value," she added.

The price to be paid here is simply the time spent watching. That time, presumably, being the same for either version of TV, that home grown loveliness or that irritating colonial import. The concern here is that people preferentially watch the imports. While the claim is also made that people really value the lovely local product.

It is not possible for both of these to be true. Reality is the very thing being complained about. That people preferentially watch the foreign muck. As they do so they therefore do not value the local. At which point there’s nothing that needs to be done, is there?

We have preferences being revealed in an entirely open and free market. Why on earth would we want to change anything?