The good old days are right now - and don't forget it

The Guardian offers a reader question - “Were people happier in the good old days? And when was that?”

To which the correct answer comes in two parts. The first being the good old days - that’s right now. This moment, this instant. We’re unsure of what the future is going to be although we can assume, with pretty good odds, that it will continue to improve. As long as we don’t elect those who will offer us Venezuela, or Zimbabwe, as a societal pathway. Compared to the past though it is now which is good.

We’re richer, live longer lives, have more choices, are, in general, just the generation of our species living highest upon the hog. At levels quite literally beyond the dreams or imagination of those significantly before us.

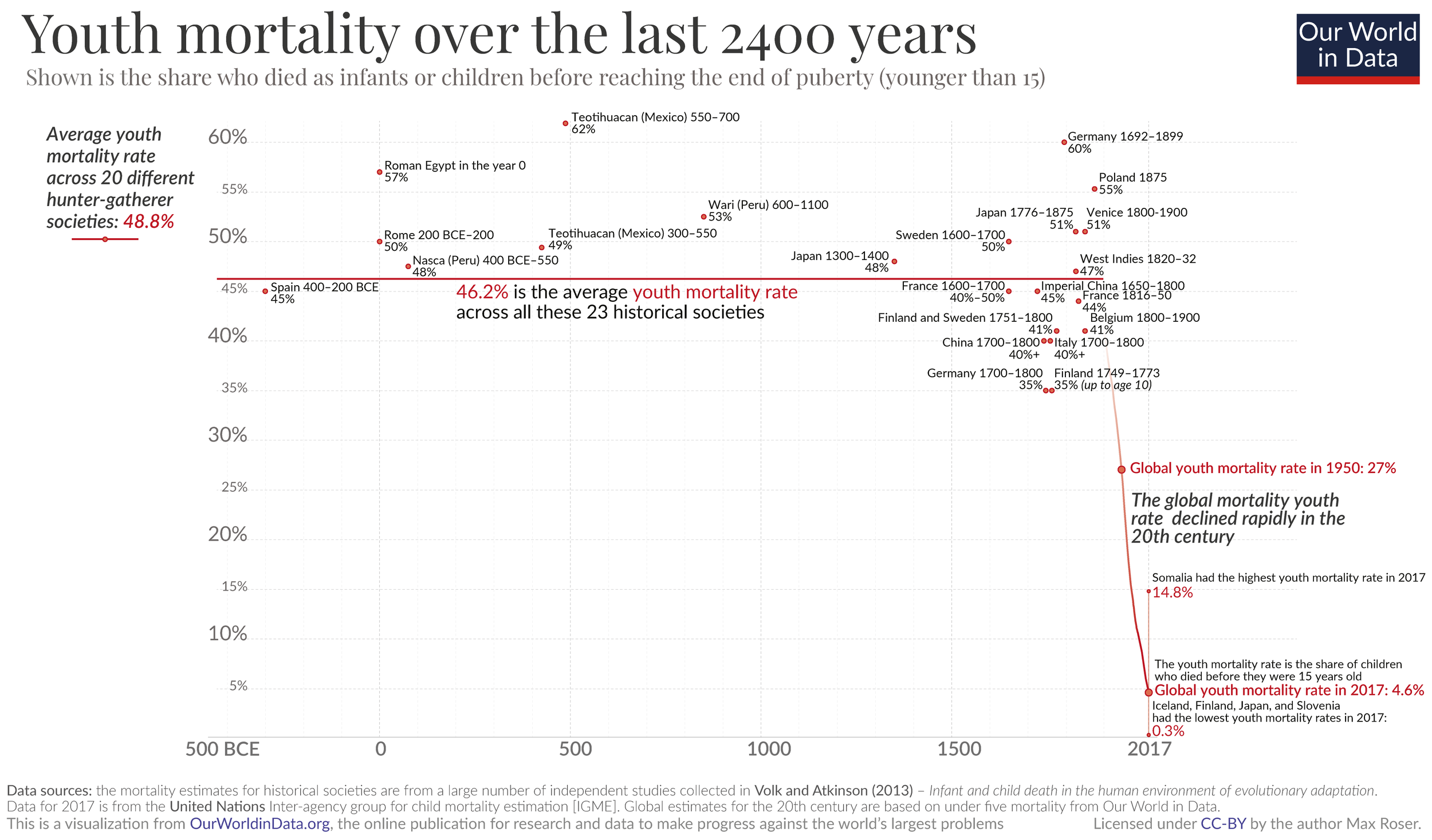

Just the one example, given the stories about those Canadian First Nations schools in the current news. The claim is of a 3% or so death rate among the pupils. Dependent upon how we count - infant deaths or all youth or just school age - that’s around the current global rate, the UK rate in the year of this specific author’s birth or possibly well under one tenth of the global historical rate.

It is precisely because things have got so much better that those historical numbers currently shock.

The good old days are now.

However, happier is more complex, one correspondent grasping this point:

People had lower expectations and were less bombarded with images of all the other lives they could be aspiring to.

The nub here is that second important lesson of economics, there are always opportunity costs. The true price of something is what is given up to get it. If we have more choices then the price of gaining any one of them is giving up many more of those alternatives.

This is why all those surveys showing that female - self-reported - happiness has been declining to standard male levels over recent decades. That wholly righteous economic and social liberation of women has led to greater choice and thus higher opportunity costs. As women gain those same choices as men therefore happiness rates converge.

There are those who take this to mean that society should regress, to where those opportunity costs are lower and therefore we would be happier. The correct answer to which is that 50% child mortality rates did not in fact make people happier.

We’ll take the vague unease of having so many choices over parents having to bury half their children, thank you very much, we really do think we’re all truly happier this way around.

The latterday Malthusians

Robert Malthus (1766-1834) is very much alive and well and living among us. His 1798 book, “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” made the point that starvation must come because population multiplies geometrically and food supply does so arithmetically. When a nation’s food supply increases, so does its population, until it reaches back again to subsistence and famine. In the future, said Malthus, there would not be enough food to sustain the whole of humanity, so people would starve.

By a coincidence, it ceased to be true the moment he published it because the world was on the cusp of a shift to the mechanized mass-production that characterized the Industrial Revolution’s bridge to the modern world. Those innovations extended to agriculture and expanded food production.

The modern Malthusians have included Paul R Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb, published in 1968. It said that the battle to feed the world had been lost, and that in the 1970s hundreds of millions of people would die of starvation. Ehrlich has published many revisions of the book, always maintaining his thesis, but pushing the catastrophe dates forward.

By another coincidence, Ehrlich’s thesis ceased to be true even as he was publishing it. Norman Borlaug was at the time developing the Green Revolution, using high-yielding grains, expanded irrigation, modern management techniques, hybridized seeds, and the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Borlaug was reckoned to have saved over one billion lives, and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, two years after Ehrlich’s book came out.

More Malthusians came along in 1972 when the Club of Rome commissioned “The Limits to Growth,” predicting that the future would bring "sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity" (i.e. starvation and poverty). They looked at five variables: “population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and consumption of nonrenewable natural resources,” and assumed that all of them would grow exponentially, whereas the ability of technology to increase resources would grow only linearly. Critics immediately decried is as “simplistic,” underrating the role of technological progress in solving the problems of resource depletion, pollution, and food production.

The rise of obesity as a major problem has rather put starvation onto the back burner, but latterday Malthusians now stress other reasons why unchecked population increases will bring disaster. These include resource depletion, pollution, greenhouse gases, and even that there will not be enough space for everyone. All of these help to reinforce a Project Fear designed to force people to change their ways.

But along come renewable and clean energy production, electric and hydrogen powered vehicles, lab-grown meats, genetic engineering, CRISPR gene editing and Artificial Intelligence, among others that show the pace of technological advance is accelerating rather than increasing linearly. Modern projections predict the world population to peak at 10 billion, then decline. This is a manageable figure. And it looks as though the modern Malthusians will be confounded in their gloom by the one unlimited resource of human ingenuity and creativity. It will prove them as wrong as their predecessor was.

Violence is History's Great Leveller

The authors of the classical utopian novels were obsessed with the notion of equality. In almost every design of a utopian system, private ownership of the means of production (and sometimes even all private property) is abolished, as is any distinction between rich and poor. In philosopher Tommaso Campanella’s 1602 novel The City in the Sun, almost all of the city’s inhabitants, whether male or female, wear the same clothes. And in Johann Valentin Andreae’s utopian Description of the Republic of Christianopolis there are only two types of clothing. Even the architecture of the houses is entirely uniform in many utopian novels. Hardly anyone who bemoans “social inequality” would today dream of advocating such radical egalitarianism. Almost everyone accepts that there should be differences in income, but – many add – these differences should not be “too big.” But what is “too big” and what is okay?

The price of equality

Another question that is all too rarely asked is: What would be the price of eliminating inequality? In 2017, the renowned Stanford historian and scholar of ancient history Walter Scheidel presented an impressive historical analysis of this question: The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. He concludes that societies that have been spared mass violence and catastrophes have never experienced substantial reductions in inequality.

Substantial reductions in inequality have only ever been achieved as the result of violent shocks, primarily consisting of:

War,

Revolution,

State failure and systems collapse, and

Plague.

According to Scheidel, the greatest levellers of the twentieth century did not include peaceful social reforms, they were the two World Wars and the communist revolutions. More than 100 million people died in each of the two World Wars and in the communist social experiments.

Total war as a great leveller

World War II serves as Scheidel’s strongest example of “total war” levelling. Take Japan: In 1938, the wealthiest 1 percent of the population received 19.9 percent of all reported income before taxes and transfers. Within the next seven years, their share dropped by two-thirds, all the way down to 6.4 percent. More than half of this loss was incurred by the richest tenth of that top bracket: their income share collapsed from 9.2 percent to 1.9 percent in the same period, a decline by almost four-fifths. The declared real value of the income of the largest 1 percent of estates in Japan’s population fell by 90 percent between 1936 and 1945 and by almost 97 percent between 1936 to 1949. The top 0.1 percent of all estates lost even more during this period, 93 and 98 percent, respectively. During this period, the Japanese economic system was transformed as state intervention gradually created a planned economy that preserved only a facade of free market capitalism. Executive bonuses were capped, rental income was fixed by the authorities, and between 1935 and 1943 the top income tax rate in Japan doubled.

Significant levelling also took place in other countries during wartime. According to Scheidel’s analysis, the two World Wars were among the greatest levellers in history. The average percentage drop of top income shares in countries that actively fought in World War II as frontline states was 31 percent of the pre-war level. This is a robust finding because the sample consists of a dozen countries. The only two countries in which inequality increased during this period were also those farthest from the major theatres of war (Argentina and South Africa).

Low savings rates and depressed asset prices, physical destruction and the loss of foreign assets, inflation and progressive taxation, rent and price controls, and nationalisation all contributed in varying degrees to equalisation. The wealth of the rich was dramatically reduced in the two World Wars, whether countries lost or won, suffered occupation during or after the war, were democracies or run by autocratic regimes.

The economic consequences of the two World Wars were therefore devastating for the rich – a fact that stands in direct opposition to the thesis that it was capitalists that instigated the wars in pursuit of their own economic interests. Contrary to the popular perception that the lower classes suffered most in the wars, in economic terms it was the capitalists who were the biggest losers.

Incidentally, the left-wing economist Thomas Piketty comes to a similar conclusion. In his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, he argues that progressive taxation in the twentieth century was primarily a product of the two World Wars and not of democracy.

Poverty is eliminated peacefully

The price of reducing inequality has thus usually involved violent shocks and catastrophes, whose victims have been not only the rich, but millions and millions of people. Neither nonviolent land reforms nor economic crises nor democratisation has had as great a levelling effect throughout recorded history as these violent upheavals. If the goal is to distribute income and wealth more equally, says historian Scheidel, then we simply cannot close our eyes to the violent ruptures that have so often proved necessary to achieve that goal. We must ask ourselves whether humanity has ever succeeded in equalising the distribution of wealth without considerable violence. Analysing thousands of years of human history, Scheidel’s answer is no. This may be a depressing finding for many adherents of egalitarian ideas.

However, if we shift perspective, and ask not “How do we reduce inequality?” but "How do we reduce poverty?" then we can provide an optimistic answer: not violent ruptures of the kind that led to reductions of inequality, but very peaceful mechanisms, namely innovations and growth, brought about by the forces of capitalism, have led to the greatest declines in poverty. Or, to put it another way: the greatest “levellers” in history have been violent events such as wars, revolutions, state and systems collapses, and pandemics, but the greatest poverty reducer in history has been capitalism. Before capitalism came into being, most of the world’s population was living in extreme poverty – in 1820, the rate stood at 90 percent. Today, it’s down to less then 10 percent. And the most remarkable aspect of all this progress is that, in the recent decades since the end of communism in China and other countries, the decline in poverty has accelerated to a pace unmatched in any previous period of human history. In 1981, the rate was still 42.7 percent; by 2000, it had fallen to 27.8 percent, and in 2021 it was only 9.3 percent.

Rainer Zitelmann is the author of The Power of Capitalism https://the-power-of-capitalism.com/

We're struggling to understand The Guardian's logic here

We agree entirely that the move to working from home is going to require a change in the planning system for housing. Building the smallest new housing in Europe doesn’t make sense when people are to be working and living in the same place. Further, we can imagine that even the most determined Nimby or Banana (build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone) could be persuaded that a switch in the built environment from workspaces to living ones is OK.

Proof of widening housing and wealth inequality caused by the pandemic already exists. Price inflation over the past year was driven by owners using savings to get hold of more space, as well as the chancellor’s decision to give buyers a stamp duty holiday (£180bn is estimated to have been added to household savings, with home workers in better paid and professional jobs the least likely to have been laid off or furloughed). Prices of detached homes rose 10% – twice as much as flats – with rural areas seeing the highest rises.

Just for the sake of argument accept that point. The gap between those who own and those who rent is growing and it’s a bad idea. The logical struggle comes here:

More secure and longer tenancies, and a huge increase in the supply of social housing, were desperately needed before; the signs are that ever greater numbers working from home will only intensify that need.

If the thing to be worried about is the divide between owners and renters then why is the solution an expansion of the rental sector?

The correct solution would seem to be freeing the housing market so that houses people wish to live in are built where they wish to live. We can then leave the market to sort out tenancies and size. You know, blow up the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 and successors.

The treason of the intellectuals

The phrase “La Trahison des Clercs” was the title of a 1927 book by the French Philosopher Julien Benda (1867-1956). It was published in translation in the US as “The Treason of the Intellectuals,” and in the UK as “The Great Betrayal.” Its theme was that the European Intellectuals of the 19th and 20th Century had abandoned their duty to judge political and military events from afar, bringing the light of reason and understanding to interpret the developments of their day, and had instead chosen to take sides with the less desirable and less humane ideas of their times. Instead of exposing and opposing populism, nationalism, crude racism and the military adventurism that swept across various countries of Europe, they had, in effect, chosen to endorse such developments and become their apologists.

He called it treason because he believed that intellectuals had a duty to uphold civilized values against the tides of unreason that raged across the Continent. Just as we speak of “noblesse oblige,” meaning that those in privileged positions have a moral duty to engage in honourable, generous and responsible behaviour, Benda’s view could be described as supporting the idea of “sagesse oblige,” requiring that those endowed with wisdom, learning and understanding have a similar moral imperative to comment on events in a dispassionate and intellectually honest way, rather than being swept along by the tides of passion that moves those less well endowed with intellect and insight.

We see today a similar abandonment of duty by those in our university seats of authority, and in those appointed to preserve and protect our national institutions and to extend their value and their heritage to the general citizenry of the country as widely as possible.

University vice-chancellors, and indeed their lecturers and professors, have an implicit and understood duty to preserve the status of a university as what Disraeli described as “a place of light, of liberty and of leaning.” They are places where ideas should be expounded and challenged, where values should be subject to scrutiny, and where views, even outlandish views, should be free to strut upon the stage and receive the support or rejection of the audience. They should be a ferment of intellectual challenge and conflict, rather than places where people can feel comfortable and secure listening to the unchallenged echoes of their existing prejudices.

Institutions such as the National Trust, the British Museum and others, have a duty to make widely accessible the heritage that inheres in them, and let people learn from the past and what it has bequeathed to the present. It is not their purpose to judge all of the past by the standards of the present, and to discard or diminish its achievements because it derives from societies that had different values to those we hold today. Humans advance in moral resources as well as in physical ones, and should not denigrate or despise all of the past because it failed to live by today’s higher standards. Past thinkers and statesmen lived by the standards of their day, just as we do.

We expect students to challenge authority; it’s what they do and have always done. It’s how ideas are formed. What we do not expect and should not accept is the treason of the intellectuals who should be upholding and defending their right to do so, but are instead falling supinely before the demands of a few outspoken voices to curb freedom of expression and open debate. As Edmund Burke said, ““Because half a dozen grasshoppers under a fern make the field ring with their importunate chink…do not imagine that those who make the noise are the only inhabitants of the field.”

It may be time for those who commit Benda’s “treason of the intellectuals” to be removed and replaced by others who do not.

Illogic and the perils of groupthink in the producer interest

There’s a certain illogic here:

Second, women’s healthcare is under-researched and under-evidenced.

It is possible that is true but we’d insist that it rather conflicts with this piece of evidence:

It is a miracle of modern medicine that the joy of getting pregnant no longer has to be tempered with the very real prospect that you or your baby may not survive the birth. A true marker of human progress is the fact that maternal and infant mortality have dropped dramatically in the UK even as births have become more complicated, with babies getting bigger and women having children later.

As Sonia Sadha goes on to point out the historical figures for au naturelle birth were maternal death rates of perhaps one in 25. Per vivparity that was, not per lifetime. A reasonable guess at today’s number for the UK is 0.012% or so, not that 4%.

We’d not claim that as a result of something being under-researched.

However, on the second point:

Until just a few years ago, this was widely embraced by the establishment: a working group including the National Childbirth Trust, the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, advocated for “normal birth” without medical interventions such as an epidural or caesarian section.

This has certainly been a factor in women and babies being denied life-saving care: at Morecambe Bay, midwives pursued non-medical births “at any cost”, bullying those doctors who tried to intervene. At Shrewsbury and Telford, there was a multi-professional focus on “normal birth” at “pretty much any cost”.

Entirely so. A certain groupthin, a coalescing, among the producer interest, around a specific ideology and set of practices. And damn the consumer interest, this is what we shall impose whether the customers - sorry, patients - like it or not.

Which is the argument against having a monopoly upon the supply of anything, isn’t it?

Is the flying car commercially viable?

A car that can fly has been a dream for over a century. Every few years a prototype is tested, but none ever go into production. One was flown by Christopher Lee in the Bond movie, “The Man with the Golden Gun.” Last week a new prototype was flown on a 35-minute flight between two international airports. It was the Aircar, made by Klein Vision, that uses regular petrol-pump fuel to power a BMW engine, and can carry 2 people at a cruising speed of 106 miles an hour.

Apparently it takes two minutes and 15 seconds to transform it from a car into an aircraft, and can fly 600 miles at a height of 8,200 feet. The company behind it says the prototype has taken about two years to develop and cost "less than 2m euros" (£1.7m) in investment.

It’s great that people in a market-driven capitalist economy will put up money like this to back new concepts in the hope of capturing a lucrative share of the market. The customers out there will separate out those who get it right, by providing them with what they want, from those who fail to do so.

It’s certainly a cool-looking vehicle, but as a commercial prospect I doubt it will fly (so to speak). To fly it you will need a pilot’s licence with all the training that goes into obtaining one. You need an airport and a runway to take off from. The company seems to think the Aircar’s competitors are other light aircraft, but the likelihood instead is that they will be passenger-carrying drones flown and controlled by Artificial Intelligence. People will not need pilot’s licences to travel in them, and they will be able to take off vertically from buildings or parks rather than from distant airports. They will use electricity rather than fossil fuels, and will probably be much quieter. Several prototypes of such vehicles have already been flown or are under development. When they are operating they will reduce road congestion and journey times, and take some of the strain off transport infrastructure.

All credit, however, to the inventors and designers who have produced what seems to be a valid, workable version of the long-dreamed-of flying car. It might work, perhaps cornering a small niche of the light aircraft market. But to play a significant role in mass transit, it might have arrived on the scene too late, drawing on a technology that is about to be replaced by a newer one. As with other market innovations, it will have to face the test of the consumers. Will they buy it?

The glory of those self-solving problems

Time was when the British supermarkets were renowned for the fatness of their margins, the richness of their profits. So much so that the 1990s saw an investigation into what should be done.

BRITAIN'S pounds 60bn supermarket industry is facing another lengthy investigation into alleged profiteering after the Office of Fair Trading yesterday referred the sector to the Competition Commission.

The commission has been given 12 months to report on whether a monopoly exists amongst the supermarkets and whether they exploit that power against the public interest.

Note that was at least the second - memory dims as we go further back than that. No one did very much about it other than study the problem of course. Which meant it was all repeated near a decade later:

CONSUMER watchdog the Office of Fair Trading is to refer the role of supermarkets in the UK grocery market to the Competition Commission for an inquiry.

No one did very much about it other than study the problem of course. Good jobs with fat paycheques in studying.

And today?

Most seriously of all, the deep discounters Aldi and Lidl moved aggressively into the UK market, with a limited range, low cost formula that the big chains struggled to match. The result? Not much growth, and not much in the way of profits.

The fatness of those margins, the richness of those profits, attracted the greed - sorry, enlightened self-interest - of other capitalists. This competed away the richness of those profits, the fatness of those margins.

Which is how capitalist and market economies work.

We do indeed face problems in this vale of tears and yet by getting the basic system right we find that many of them are self-solving. Isn’t that lovely?

There might be a reason George Eustice is at environment

This appears to be coming from George Eustice at whatever the environment agency is called these days. At least, it’s going out over his name which makes him the Minister responsible:

The decision means that companies exporting brands such as Evian, Volvic, Perrier and St Pellegrino will face additional red tape. Last year, about €114m (£98m) worth of mineral water was imported to the UK from the EU, according to the Eurostat agency. Currently any water recognised as “natural mineral water” by an authority in an EU member state is automatically recognised in the UK. From Jan 7, suppliers will have to have their water recognised by Food Standards Scotland, Defra or the Food Standards Agency, or be banned from Britain. British mineral waters have had to apply for recognition in an EU member state before exporting to the bloc since Brexit took effect on Dec 31.

As everyone who has ever bothered to crack open an economics book knows the purpose of trade is to get our hand - or gullets - upon those lovely things made by Johnny Foreigner. Putting bureaucratic barriers in the way of our doing so is therefore not a good trade policy.

Note that no claim is being made that those foreign regulations are no good, inadequate or lacking in some manner. The actual claim being made is that the governments of the remnant European Union are making their citizenry poorer therefore the British government must make Britons poorer in retaliation.

This doesn’t really work as logic now, does it? It being just yet another proof that the correct tit for tat response to repeated iterations of the Prisoners’ Dilemma does not work for trade issues. The actual correct trade policy, even in the face of provocations by those damn’d foreigners, is unilateral free trade. You do whatever you want and we’ll do what is best for our folks here at home.

That best being that the British government should not be putting artificial barriers in the way of Britons enjoying whatever mineral water it pleases Britons to enjoy. Or, to put it the other way around, what in heck is a British minister doing deliberately plotting to make Britons poorer. Doesn’t he work for us?

Still, in that desperate search for a silver lining in absolutely anything at least he’s only at environment, not trade.

Gell Mann Amnesia, Hayek and rare earths for electric vehicle batteries

Gell Mann Amnesia is where you read a newspaper article on your own subject of expertise and note that they’ve managed to entirely cock up the sophistications and subtleties of the area to the point of being wildly misleading to completely wrong. You then turn the page to a piece outside your own area of direct knowledge and believe everything they say.

This always does happen.

Hayek’s point about trying to plan the world is that knowledge is local, no one ever does, or can, gain the necessary information to be able to plan everything in any detail.

Colin Brazier on GBNews gives us an example. This is not to attack this specific outlet, these mistakes are more general that that, this is an exemplar.

The subject is rare earths to make the batteries for electric vehicles. The claim is made that neodymium is used to do so. It isn’t. Nd is used in magnets, electromagnetism means that you use Nd to turn movement into electricity - in a turbine say - or electricity into movement - in an engine. You do not use it in a battery. You might well use lanthanum but that’s a different element, even if it is still a rare earth. The other metals mentioned, cobalt, lithium and so on, aren’t even rare earths.

Yes, this does matter because the supply problem with rare earths - a different one from many other metals - is not going mining for them. This is between relatively and entirely trivial as an exercise. There are plenty of sources, for example, in the waste streams of other mineral activities. We - we meaning any combination of the UK, US, EU and so on, whether separately or in combination - can gain access to mixed rare earths at the drop of a hat.

The problem is that “mixed” bit. The difficulty is in separating the 15 lanthanides out into their individual elements. This requires a plant that costs some $1 billion using the current technology. There is a proposal for a mini-plant to be built upon Teesside which would cost £200 million - and do about a quarter of the job, extracting only a few of them from the mixed source.

If, and we do insist upon that if, there is to be some intervention from the centre into this industry then good logic would suggest it should be in solving that separation problem, not the mining one. Good logic because the mining part isn’t a problem while the separation is.

It is even true that there is a potentially - potentially! - viable alternative technology, vacuum distillation of metal halides, which would solve that separation problem. As it happens the UK is one of only two - and of the two the better one - global centres of excellence in the basics of this technology.

Guess what isn’t being discussed as a potential British solution to this rare earths problem? Which is where that Hayek part comes in. Because the British government does think it would like to solve this problem. It’s willing to spend considerable sums on doing so too. But it doesn’t have the knowledge to have identified what the actual problem is therefore isn’t trying to solve the actual problem.

The Gell Mann part is how - we all do get our information outside our own areas of technical expertise from the media - the general conversation gets things wrong. The Hayek part is how government does. Even when there is a problem to be solved government does the wrong thing.

Which is just another reason why we’re not in favour of that government involvement in the economy, in that idea that planning will be the solution to our economic woes. Observation of that reality outside the window tells us that the information to identify problems is lacking thus solutions never are funded.

Of course, there’s always the opportunity for the government to prove us wrong here but we’ll not be holding our breath……