A certain brutality here, yet also a certain truth

Mr. Lutnik will no doubt be demonised as a very bad man, even a brutal one:

Junior bankers who complain about being burned out by long hours in the office should stop moaning and think about changing career, according to an American banking boss.

Howard Lutnick, who runs Cantor Fitzgerald, said bankers should go into the job knowing it will involve late nights and weekend work.

His view is a stark contrast to his American rivals that have given junior staff extra time off, higher pay or gifts such as Peloton bikes or Apple Watches this year amid fears of a revolt.

"Young bankers who decide they’re working too hard - choose another living is my view," Mr Lutnick told Bloomberg TV. "These are hard jobs."

With reference to the difference between American and British practices, the British already work fewer hours, even in this sector.

But as Adam Smith said - and as has been shown to be true subsequently - compensating differentials are a real thing:

The five following are the principal circumstances which, so far as I have been able to observe, make up for a small pecuniary gain in some employments, and counter-balance a great one in others: first, the agreeableness or disagreeableness of the employments themselves; secondly, the easiness and cheapness, or the difficulty and expence of learning them; thirdly, the constancy or inconstancy of employment in them; fourthly, the small or great trust which must be reposed in those who exercise them; and fiftly, the probability or improbability of success in them.

First, The wages of labour vary with the ease or hardship, the cleanliness or dirtiness, the honourableness or dishonourableness of the employment.

There is also the allied concept of efficiency wages - bankers get paid lots in order to make dipping into the cash flow an expensive thing to do if it risks losing the high income from the employment itself.

But there it is, right there. One reason bankers get high pay is because of the hardship, those long hours. Those who find it not a sufficient compensating differential should find another way of making a living.

Mr. Lutnik is right.

The whole of the advantages and disadvantages of the different employments of labour and stock must, in the same neighbourhood, be either perfectly equal or continually tending to equality. If in the same neighbourhood, there was any employment evidently either

more or less advantageous than the rest, so many people would crowd into it in the one case, and so many would desert it in the other, that its advantages would soon return to the level of other employments. This at least would be the case in a society where things were left to follow their natural course, where there was perfect liberty, and where every man was perfectly free both to chuse what occupation he thought proper, and to change it as often as he thought proper. Every man’s interest would prompt him to seek the advantageous, and to shun the disadvantageous employment.

In terms of employment in finance we are in something as close as anyone ever has been to such a completely free market. The pay reflects the hours. Sure, that might not be a trade off that all are happy with but so what? There are, as we all know, alternative employments out there with different trade offs.

We do wonder where Polly Toynbee gets her information from

Polly Toynbee tells us that:

In the last decade, the NHS budget per capita fell in a rapidly ageing population.

That doesn’t, particularly, seem to be true.

In this edition of the UK Health Accounts, healthcare expenditure consistent with the definitions of the System of Health Accounts 2011 (SHA 2011) has been estimated back to 1997 for the first time (Figure 1). Health spending between 1997 and 2018, in nominal terms, trebled, with the average annual rate of growth being 5.8%.

Controlling for inflation, healthcare expenditure more than doubled over the same period, experiencing an average annual rate of growth of 3.8%. Breaking this down into healthcare spending before and after the impact of the 2008 economic downturn, healthcare spending grew by an average rate of 5.3% per year between 1997 and 2009, slowing to an average of 1.9% between 2009 and 2018.

Estimated healthcare spending per person, in real terms, almost doubled between 1997 and 2018, rising from £1,672 per person in 1997 to £3,227 in 2018, as healthcare expenditure growth greatly exceeded population growth.

Agreed, that doesn’t include the last couple of years but we think we’d have heard about it if “the cuts” had reversed that previous 8 years of growth to give us that decade Polly claims.

There’s also a political problem here:

Voters might ignore the fiendishly complex history of NHS restructuring, but they will grasp one simple, sinister point: the government is seizing control of the everyday running of the NHS, in what the Health Service Journal calls “an audacious power grab”.

This is a corollary to Hayek’s point in The Road To Serfdom. His main one being that if government provides health care then we, the population, will be managed to benefit the health care system. Like, you know, cowering in place in order to save the NHS.

The corollary here is that Polly does insist that government be that healthcare provider. Both in financing and in providing the workforce and facilities, the treatments. And yet she seems to think that government isn’t then going to try to control what is done with that £200 billion a year and more.

That’s really not the way politics works now, is it?

We even have a logical problem here:

The then NHS CEO, David Nicholson, himself called that upheaval so colossal “it can be seen from space” as it broke the NHS into fragments, putting every service out to tender to anyone, public or private, enforced by competition law. Every part of the NHS had to bid and compete against others for any service: co-operation was illegally anti-competitive.

This is to grossly misunderstand how markets work.

Yes, there is competition, yes, competition is beneficial. But the competition isn’t between the different layers or links in the chain of provision. That always remains as cooperation. It’s between the different people - organisations - that can be any specific link in that chain.

The supermarket and I are cooperating when I buy a banana. More than that, so is everyone in the supply chain. The folks who make the refrigerated ships that carry the fruit (actually, an herb) across the ocean, the sailors upon said ship, the guy who dug the hole to put the clone of the Cavendish into it 10 years before, the people who make the fungicides, the supply chain is a masterpiece of coordination and cooperation.

Competition is between the varied alternative folks who could provide any one or more of these goods and services in that supply chain.

The cooperation makes a market work, the competition is how I get to buy the banana at 99 pence per kg.

Markets, that is, are a method of organising cooperation. Competition is just the decision about who to cooperate with. And why would we be against that?

Factual errors, illogic and an ignorance of politics. Well, it is a Polly column, isn’t it?

The view from the bubble

There is an old proverb that tells us, “Never criticize a man until you have walked a mile in his shoes.” The corollary is that you are therefore a safe mile away when you voice your criticism, and you have his shoes.

The humour notwithstanding, it can spread understanding if people try to see how the world looks from someone else’s point of view.

Analysts sometimes speak of the “Westminster bubble,” named after the Westminster centre of government and administration. It includes Parliamentarians, political staffers, those employed by NGOs, civil servants, broadcasters and academics. It is alleged that they share a common standpoint, and rarely encounter the views of those outside their mindset. They live, it is said, in an echo chamber in which they think the views they hold in common with those of their milieu are the only possible views that reasonable people can hold.

In truth, they represent a class that extends beyond Westminster. Many of them will have attended good schools and gained university degrees. They tend to work in jobs that don’t actually produce goods and services other than communication, education and government. They socialize with like-minded friends. Their parallels can be seen in other big cities as opposed to ordinary towns, sharing similar lives and holding similar views.

Most would think of themselves as internationalists, regarding patriotism as insular and outmoded. Overwhelmingly they supported the EU and voted Remain. They despised Trump and regard the Tory party with a lofty disdain. They are on the Left politically, and regard business and profits with disdain. Most of their salaries are funded directly or indirectly from taxpayer funds, so they are above what they might see as the sordid process of actually making money.

Many of them acquiesce in anti-capitalist ventures that crop us periodically, from Occupy Wall Street to Extinction Rebellion. Many think the most important issues facing humanity are equality, diversity, decolonization of the culture and such environmental causes as don’t actually limit their own lifestyle. They adopt the changes in terminology demanded by woke culture. One can only guess at their reasons for looking down on the ordinary people outside of their world. Perhaps they think their education makes them superior in other respects?

And yet there is a world beyond the bubble, a world in which ordinary people are doing their best to lead decent lives, to get by as best they can, and to do their best for their children. They are no less honourable for being outside the bubble or for working in lower status jobs, and their views are no less entitled to expression than those of the bubble people.

They are mostly patriotic, taking a low-key pride in their country and its achievements, and not denigrating its past. This does not make them xenophobic, as bubble people seem to think. They tend to be tolerant, not racist, and not opposed to those who choose different lifestyles. They are as concerned about the environment and the world their children will inherit as their bubble counterparts are, albeit in a less strident way.

If they have a complaint about modern Britain, it might be that those at the centre of its government and its culture have overlooked and ignored them and discounted their legitimate views and concerns. The response of many of them was to vote Brexit and to vote Tory, as a protest against being told how to behave and what to think by those who believe their superior status, as they see it, entitles them to do this.

The bubble is not Britain, and those who move within its confines might learn something if they looked beyond it.

Taking George Monbiot's advice to heart

George tells us that:

The lesson, to my mind, is obvious: if we fail to hold organisations to account for their mistakes and obfuscations, they’ll keep repeating them. Climate crimes have perpetrators. They also have facilitators.

This seems entirely reasonable to us. From the same edition of The Guardian we get this:

More than 8 billion people could be at risk of malaria and dengue fever by 2080 if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise unabated, a new study says.

Malaria and dengue fever will spread to reach billions of people, according to new projections.

Researchers predict that up to 4.7 billion more people could be threatened by the world’s two most prominent mosquito-borne diseases, compared with 1970-99 figures.

The figures are based on projections of a population growth of about 4.5 billion over the same period, and a temperature rise of about 3.7C by 2100.

This comes from a paper in a part of The Lancet network:

…across four RCPs (arranged from the most conservative to business-as-usual: RCP2·6, RCP4·5, RCP6·0, and RCP8·5)

Now that’s a mistake, or obfuscation, that needs to be held to account. As one of us has pointed out in significant detail that RCP 8.5 is not business as usual. It never was anything other than an unlikely edge case just to show extremes. The actions that have already been taken concerning climate change make it - without extreme and significant retrogression - unachievable as even a possible case now.

What might happen if we all party with coal like it’s 1899 is a possibly interesting rumination. But to call that a likely, even possible - let alone business as usual - future is somewhere between that mistake or obfuscation that we must hold people to account for.

Well George, what say you?

Green capitalism

Although many environmentalists say that socialism must be introduced to solve environmental problems, the environmental record of socialist counties has been very poor indeed. Other environmentalists blame capitalism for degrading the environment and call for it to be replaced without specifying what is to replace it.

Green capitalists, on the other hand, say that where capitalism has degraded the environment it is because natural resources such as the atmosphere and the oceans have not been costed. It is the tragedy of the commons that people are motivated to overuse resources that add value but cost nothing. They further say that if externalities are properly costed, people will have an incentive to use them efficiently and sparingly. They support the notion of internalizing these externalities, with many of them calling for carbon taxes and carbon trading so that the pollution costs enter the prices of products, leading people to turn to less polluting alternatives. Green capitalists argue that firms that use fewer resources such as energy, raw materials or water, find this is good for profits as well as the planet.

They further point out that if society through its governments sets targets, capitalist entrepreneurs will come up with cost effective ways of achieving them. But it’s not just governments that are doing this. Surveys report that consumers show more brand loyalty and willingness to pay higher prices for products perceived to be sustainable. This is especially true among Millennials and Generation Z, who currently make up 48% of the global marketplace and have not yet hit their peak spending levels. Firms that want to capture a chunk of that market have a financial interest in producing sustainably.

Entrepreneurs in search of profits are already making renewable energy sources more efficient, and are bringing its costs down. Renewables are technologies, not fuels, and technologies develop and improve, whereas fossil fuels remain as constants. And given the ability to produce more and more electricity from renewables, the development and spread of electric vehicles is offering a green revolution in transport. People need not travel less, but just to travel clean.

Environmentalists assume that if animal husbandry is bad for the environment, people must learn to eat less meat, but the green capitalist’s answer is to produce meat from non-animal sources such as cultured (lab-grown) meats. Capitalists are also applying GM and CRISPR technologies to enable more food to be produced on less land, leaving land free for reforestation, and thereby increasing the world’s tree cover.

The capitalist’s answer to the overfishing of the world’s seas is to insert the discipline of markets into what has been a common resource. Iceland and New Zealand now assign tradable quotas to fishing boats so that they have a commercial interest in sustaining stocks. If a boat hauls in more than its quota of designated fish, they buy quotas from other boats instead of dumping the catch, EU-style, to avoid fines.

When supermarkets, seeking profits, buy cheaper tomatoes from warmer countries rather than pay for expensive ones that need energy inputs to grow them, this has been castigated as “food miles,” but the reality is that they are effectively importing renewable sunshine from abroad rather than requiring energy resources to be expended at home.

The effect of all of this capitalist and entrepreneurial activity is to make a convincing case that protecting the environment does not require the overthrow of capitalism and markets, as many environmentalists demand. Instead it requires the application of them.

The Merchant of Brussels

We all know the plot of the Merchant of Venice. Antonio needs money in a hurry to finance his global trading ambitions and signs a contract under which Shylock can have a pound of his flesh of his choosing if he fails to repay the loan on the due date. Come the date, his ships are not back. He cannot repay the loan and the contractual text allowed Shylock to select Antonio’s heart. The sub-plot is that Shylock hates Antonio who went to the Venetian equivalents of Eton and Oxford and sees this as an opportunity to wreak vengeance. When Antonio’s friends offer to pay off the loan at many times its value, Shylock refuses. He insists that the contract was freely signed by Antonio and must be implemented to the exact letter.

Clearly it would be ridiculous to suggest that Shakespeare anticipated the Irish Protocol negotiations by 416 years, or that our Prime Minister resembles Antonio in any way, or that the EU are seeking to penalise the UK for leaving the club. Nevertheless, the parallels are there and it is interesting to recall how Shakespeare resolved the irresolvable.

The Irish Protocol was devised to avoid customs posts on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic. It may be a small island but the border is longer than that between France and Germany and more difficult to police, although customs border posts worked perfectly well for 70 years from 1923. The idea that reinstating them would infringe the Belfast Agreement is a myth invented by Dublin; nothing in that Agreement envisages Brexit.

So, a Protocol which would allow free trade between the north and south of the island is clearly a good idea especially as the master trade agreement stipulates tariff free trade between the EU and UK. Free trade within the UK, i.e. between Britain and Northern Ireland, was so obvious that it hardly needed stating so the PM affirmed there would be no border in the Irish Sea. Unfortunately Shylock’s clerks could not grasp how Northern Ireland could be part of the EU customs union, observing all its rules and regulations, at the same time as being part of the UK customs union with rules and regulations which were expected to diverge from the EU’s. Tariffs are not the issue; non-tariff barriers are.

Furthermore, the drafting clerks had a tenuous grasp of UK geography. They seem to have confused the Isle of Man, which is not part of the UK, with Northern Ireland, which is. When the PM read the draft Protocol, if he read it at all, the absence of the obvious would not have worried him any more than it worried Antonio.

Given the total commitment of the Merchant of Brussels to the signed text of the Protocol, it is no surprise that suggestions of “flexibility” and “pragmatism” fall on deaf ears. Brussels views rather trivial extensions of detailed matters, such as sausages, as hugely magnanimous and the British negotiators take credit for any crumbs they can get. That approach will not solve the fundamental problem and it was not a route that Portia, an intelligent woman, chose to take. She played Shylock at his own game: he insisted on the letter of the contract, that, no more and no less. So be it: he could take a pound of flesh but not a drop of blood.

So where, in the 63 pages of the Protocol, is there the equivalent of the drop of blood? If that can be found and cause the Protocol to collapse, another could be drawn up to meet the requirements of both the EU and the UK. The negotiators spent weeks looking for that and probably missed it because it is so obvious. We can come to that later.

The drop of blood equivalent arises from the Protocol’s uncertainty about whether Northern Ireland is part of the United Kingdom, or merely involved in a shared customs union. This is a key point because the Protocol sees Northern Ireland as becoming part of the EU customs union but does not claim it is part of the EU.

Some Protocol clauses imply that Northern Ireland is indeed merely linked to, but not an integral part of, the United Kingdom. For example, one of the introductory clauses:

“RECALLING that Northern Ireland is part of the customs territory of the United Kingdom and will benefit from participation in the United Kingdom's independent trade policy,”

And Article 4 of the Protocol:

“Article 4: Customs territory of the United Kingdom:

Northern Ireland is part of the customs territory of the United Kingdom. Accordingly, nothing in this Protocol shall prevent the United Kingdom from including Northern Ireland in the territorial scope of any agreements it may conclude with third countries, provided that those agreements do not prejudice the application of this Protocol. In particular, nothing in this Protocol shall prevent the United Kingdom from concluding agreements with a third country that grant goods produced in Northern Ireland preferential access to that country’s market on the same terms as goods produced in other parts of the United Kingdom. Nothing in this Protocol shall prevent the United Kingdom from including Northern Ireland in the territorial scope of its Schedules of Concessions annexed to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994.”

This confusion about Northern Ireland being fully part of the UK seems to be widespread amongst continental politicians. If one was to take a “pragmatic” view of implementing the Protocol then these matters would be swept away but if one takes the Shylock enforcing the literal approach, as the EU does, then the confusion undermines the very essence of the contract. The Protocol is a contract between two legal entities, the UK and the EU. If Northern Ireland is not an integral part of the UK, it is a separate country and not bound by the Protocol. Note that no Northern Ireland politicians were involved in the original Protocol negotiations, nor the renegotiations since. When I queried this with the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland on May 21st, he said it was nothing to do with them; it was purely a matter for London and Brussels.

Whether or not a judge would agree that this issue is enough to void the contract, is debatable. The case is certainly not strong and it may be regarded as academic because the need for a better Protocol is far more important. The relationship these days between Dublin and Belfast is pretty good and it is far more likely that they could not only find a solution but believe they own it. How much loyalty did London imagine Ulster politicians would give whatever Protocol London negotiated if the Ulster politicians were excluded?

At present the DUP focuses on the removal of the present Protocol when its replacement by a workable Protocol of some sort, one that meets the needs of the two parties in Ireland as well as the UK and the EU, is of far greater importance. Northern Ireland being in the two competing customs unions at the same time would be feasible if the UK regulations apply to goods supplied from Britain for consumption in Northern Ireland, whereas EU regulations apply to goods created in Northern Ireland for consumption in Northern Ireland or the EU. The contentious issue has been goods supplied from Britain to Northern Ireland intended for the Republic, or at risk of being consumed there. As it happens, the Republic makes plenty of its own sausages, similar to UK ones but of a different shape. There is minimal, if any, demand for UK sausages in the EU.

This problem could be solved by shipping all goods intended for the Republic, directly to the Republic, and labelling goods intended for Northern Ireland in a way that would make them unsaleable in the Republic, e.g. priced in sterling not euros or marked “For sale in Northern Ireland only”. It should be a matter for EU trading officers to deal with offenders within the EU, not a matter for UK officials.

No doubt Portia could make a better job of unravelling this matter than I have. What should be obvious to the negotiators, but seems not to be, is that the Protocol is fundamentally unfair and will cause serious trouble unless they stop tinkering and replace it with something sensible. By the way, Antonio’s ships did eventually return and he lived happily ever after.

The good old days are right now - and don't forget it

The Guardian offers a reader question - “Were people happier in the good old days? And when was that?”

To which the correct answer comes in two parts. The first being the good old days - that’s right now. This moment, this instant. We’re unsure of what the future is going to be although we can assume, with pretty good odds, that it will continue to improve. As long as we don’t elect those who will offer us Venezuela, or Zimbabwe, as a societal pathway. Compared to the past though it is now which is good.

We’re richer, live longer lives, have more choices, are, in general, just the generation of our species living highest upon the hog. At levels quite literally beyond the dreams or imagination of those significantly before us.

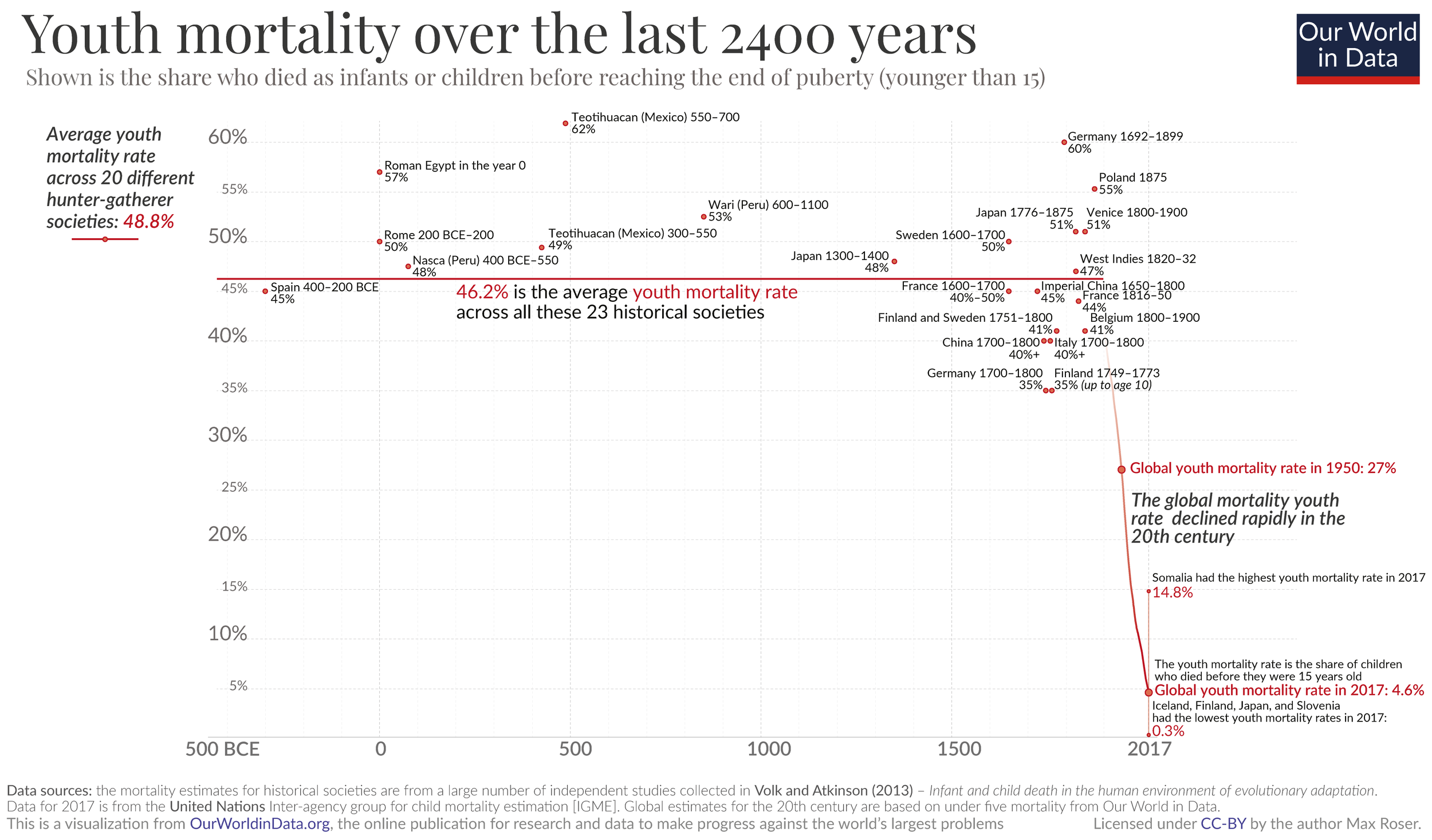

Just the one example, given the stories about those Canadian First Nations schools in the current news. The claim is of a 3% or so death rate among the pupils. Dependent upon how we count - infant deaths or all youth or just school age - that’s around the current global rate, the UK rate in the year of this specific author’s birth or possibly well under one tenth of the global historical rate.

It is precisely because things have got so much better that those historical numbers currently shock.

The good old days are now.

However, happier is more complex, one correspondent grasping this point:

People had lower expectations and were less bombarded with images of all the other lives they could be aspiring to.

The nub here is that second important lesson of economics, there are always opportunity costs. The true price of something is what is given up to get it. If we have more choices then the price of gaining any one of them is giving up many more of those alternatives.

This is why all those surveys showing that female - self-reported - happiness has been declining to standard male levels over recent decades. That wholly righteous economic and social liberation of women has led to greater choice and thus higher opportunity costs. As women gain those same choices as men therefore happiness rates converge.

There are those who take this to mean that society should regress, to where those opportunity costs are lower and therefore we would be happier. The correct answer to which is that 50% child mortality rates did not in fact make people happier.

We’ll take the vague unease of having so many choices over parents having to bury half their children, thank you very much, we really do think we’re all truly happier this way around.

The latterday Malthusians

Robert Malthus (1766-1834) is very much alive and well and living among us. His 1798 book, “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” made the point that starvation must come because population multiplies geometrically and food supply does so arithmetically. When a nation’s food supply increases, so does its population, until it reaches back again to subsistence and famine. In the future, said Malthus, there would not be enough food to sustain the whole of humanity, so people would starve.

By a coincidence, it ceased to be true the moment he published it because the world was on the cusp of a shift to the mechanized mass-production that characterized the Industrial Revolution’s bridge to the modern world. Those innovations extended to agriculture and expanded food production.

The modern Malthusians have included Paul R Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb, published in 1968. It said that the battle to feed the world had been lost, and that in the 1970s hundreds of millions of people would die of starvation. Ehrlich has published many revisions of the book, always maintaining his thesis, but pushing the catastrophe dates forward.

By another coincidence, Ehrlich’s thesis ceased to be true even as he was publishing it. Norman Borlaug was at the time developing the Green Revolution, using high-yielding grains, expanded irrigation, modern management techniques, hybridized seeds, and the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Borlaug was reckoned to have saved over one billion lives, and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970, two years after Ehrlich’s book came out.

More Malthusians came along in 1972 when the Club of Rome commissioned “The Limits to Growth,” predicting that the future would bring "sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity" (i.e. starvation and poverty). They looked at five variables: “population, food production, industrialization, pollution, and consumption of nonrenewable natural resources,” and assumed that all of them would grow exponentially, whereas the ability of technology to increase resources would grow only linearly. Critics immediately decried is as “simplistic,” underrating the role of technological progress in solving the problems of resource depletion, pollution, and food production.

The rise of obesity as a major problem has rather put starvation onto the back burner, but latterday Malthusians now stress other reasons why unchecked population increases will bring disaster. These include resource depletion, pollution, greenhouse gases, and even that there will not be enough space for everyone. All of these help to reinforce a Project Fear designed to force people to change their ways.

But along come renewable and clean energy production, electric and hydrogen powered vehicles, lab-grown meats, genetic engineering, CRISPR gene editing and Artificial Intelligence, among others that show the pace of technological advance is accelerating rather than increasing linearly. Modern projections predict the world population to peak at 10 billion, then decline. This is a manageable figure. And it looks as though the modern Malthusians will be confounded in their gloom by the one unlimited resource of human ingenuity and creativity. It will prove them as wrong as their predecessor was.

Violence is History's Great Leveller

The authors of the classical utopian novels were obsessed with the notion of equality. In almost every design of a utopian system, private ownership of the means of production (and sometimes even all private property) is abolished, as is any distinction between rich and poor. In philosopher Tommaso Campanella’s 1602 novel The City in the Sun, almost all of the city’s inhabitants, whether male or female, wear the same clothes. And in Johann Valentin Andreae’s utopian Description of the Republic of Christianopolis there are only two types of clothing. Even the architecture of the houses is entirely uniform in many utopian novels. Hardly anyone who bemoans “social inequality” would today dream of advocating such radical egalitarianism. Almost everyone accepts that there should be differences in income, but – many add – these differences should not be “too big.” But what is “too big” and what is okay?

The price of equality

Another question that is all too rarely asked is: What would be the price of eliminating inequality? In 2017, the renowned Stanford historian and scholar of ancient history Walter Scheidel presented an impressive historical analysis of this question: The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. He concludes that societies that have been spared mass violence and catastrophes have never experienced substantial reductions in inequality.

Substantial reductions in inequality have only ever been achieved as the result of violent shocks, primarily consisting of:

War,

Revolution,

State failure and systems collapse, and

Plague.

According to Scheidel, the greatest levellers of the twentieth century did not include peaceful social reforms, they were the two World Wars and the communist revolutions. More than 100 million people died in each of the two World Wars and in the communist social experiments.

Total war as a great leveller

World War II serves as Scheidel’s strongest example of “total war” levelling. Take Japan: In 1938, the wealthiest 1 percent of the population received 19.9 percent of all reported income before taxes and transfers. Within the next seven years, their share dropped by two-thirds, all the way down to 6.4 percent. More than half of this loss was incurred by the richest tenth of that top bracket: their income share collapsed from 9.2 percent to 1.9 percent in the same period, a decline by almost four-fifths. The declared real value of the income of the largest 1 percent of estates in Japan’s population fell by 90 percent between 1936 and 1945 and by almost 97 percent between 1936 to 1949. The top 0.1 percent of all estates lost even more during this period, 93 and 98 percent, respectively. During this period, the Japanese economic system was transformed as state intervention gradually created a planned economy that preserved only a facade of free market capitalism. Executive bonuses were capped, rental income was fixed by the authorities, and between 1935 and 1943 the top income tax rate in Japan doubled.

Significant levelling also took place in other countries during wartime. According to Scheidel’s analysis, the two World Wars were among the greatest levellers in history. The average percentage drop of top income shares in countries that actively fought in World War II as frontline states was 31 percent of the pre-war level. This is a robust finding because the sample consists of a dozen countries. The only two countries in which inequality increased during this period were also those farthest from the major theatres of war (Argentina and South Africa).

Low savings rates and depressed asset prices, physical destruction and the loss of foreign assets, inflation and progressive taxation, rent and price controls, and nationalisation all contributed in varying degrees to equalisation. The wealth of the rich was dramatically reduced in the two World Wars, whether countries lost or won, suffered occupation during or after the war, were democracies or run by autocratic regimes.

The economic consequences of the two World Wars were therefore devastating for the rich – a fact that stands in direct opposition to the thesis that it was capitalists that instigated the wars in pursuit of their own economic interests. Contrary to the popular perception that the lower classes suffered most in the wars, in economic terms it was the capitalists who were the biggest losers.

Incidentally, the left-wing economist Thomas Piketty comes to a similar conclusion. In his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, he argues that progressive taxation in the twentieth century was primarily a product of the two World Wars and not of democracy.

Poverty is eliminated peacefully

The price of reducing inequality has thus usually involved violent shocks and catastrophes, whose victims have been not only the rich, but millions and millions of people. Neither nonviolent land reforms nor economic crises nor democratisation has had as great a levelling effect throughout recorded history as these violent upheavals. If the goal is to distribute income and wealth more equally, says historian Scheidel, then we simply cannot close our eyes to the violent ruptures that have so often proved necessary to achieve that goal. We must ask ourselves whether humanity has ever succeeded in equalising the distribution of wealth without considerable violence. Analysing thousands of years of human history, Scheidel’s answer is no. This may be a depressing finding for many adherents of egalitarian ideas.

However, if we shift perspective, and ask not “How do we reduce inequality?” but "How do we reduce poverty?" then we can provide an optimistic answer: not violent ruptures of the kind that led to reductions of inequality, but very peaceful mechanisms, namely innovations and growth, brought about by the forces of capitalism, have led to the greatest declines in poverty. Or, to put it another way: the greatest “levellers” in history have been violent events such as wars, revolutions, state and systems collapses, and pandemics, but the greatest poverty reducer in history has been capitalism. Before capitalism came into being, most of the world’s population was living in extreme poverty – in 1820, the rate stood at 90 percent. Today, it’s down to less then 10 percent. And the most remarkable aspect of all this progress is that, in the recent decades since the end of communism in China and other countries, the decline in poverty has accelerated to a pace unmatched in any previous period of human history. In 1981, the rate was still 42.7 percent; by 2000, it had fallen to 27.8 percent, and in 2021 it was only 9.3 percent.

Rainer Zitelmann is the author of The Power of Capitalism https://the-power-of-capitalism.com/

We're struggling to understand The Guardian's logic here

We agree entirely that the move to working from home is going to require a change in the planning system for housing. Building the smallest new housing in Europe doesn’t make sense when people are to be working and living in the same place. Further, we can imagine that even the most determined Nimby or Banana (build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone) could be persuaded that a switch in the built environment from workspaces to living ones is OK.

Proof of widening housing and wealth inequality caused by the pandemic already exists. Price inflation over the past year was driven by owners using savings to get hold of more space, as well as the chancellor’s decision to give buyers a stamp duty holiday (£180bn is estimated to have been added to household savings, with home workers in better paid and professional jobs the least likely to have been laid off or furloughed). Prices of detached homes rose 10% – twice as much as flats – with rural areas seeing the highest rises.

Just for the sake of argument accept that point. The gap between those who own and those who rent is growing and it’s a bad idea. The logical struggle comes here:

More secure and longer tenancies, and a huge increase in the supply of social housing, were desperately needed before; the signs are that ever greater numbers working from home will only intensify that need.

If the thing to be worried about is the divide between owners and renters then why is the solution an expansion of the rental sector?

The correct solution would seem to be freeing the housing market so that houses people wish to live in are built where they wish to live. We can then leave the market to sort out tenancies and size. You know, blow up the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 and successors.