Irish Protocol: Why can’t the Government Listen?

Three routes to resolving the Irish Protocol crisis are considered: last week’s government command paper, “feint” and “The Trojan Horse”. The command paper is well written and sets out the way the Government thinks the Protocol should have been written, as well as some of the reasons why it was not. The future use of Article 16 is flagged. The trouble is that the EU rather likes the Protocol the way it is: the UK is being penalized for Brexit, the Republic of Ireland is benefiting from trade diverted from Great Britain and it all moves Northern Ireland closer to merger with the Republic, as the latter, and now the EU, have long sought.

Unsurprisingly, the EU immediately responded in the same way it has greeted all previous suggestions for re-negotiation: “no”. Triggering Article 16 and some blathering about it being nicer if we all got along better apart, the paper gave no reason for the EU to wish to re-negotiate. That is either Einstein’s definition of insanity or ministers are just not listening.

On 15th July, the Commons held an important debate on the Protocol. Some excellent and constructive suggestions were made, two were the diversion of trade from Great Britain to the Republic of Ireland (which contravenes the protocol) and the “manageable alternative” suggested by Lord Trimble writing in the Times on June 10th: under the heading “EU intransigence threatens the Good Friday Agreement”. As one of its two authors, he should know what he is talking about. He went on to write “A couple of years ago I had a meeting with Michel Barnier in which mutual enforcement of trade rules by the UK and the EU was discussed.” He said this suggestion had been well received by the EU but maybe the UK government was not listening.

Sir Bernard Jenkin opened the debate and drew attention, inter alia, to the diversion of trade. He said “article 16 states: ‘If the application of this Protocol leads to serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties that are liable to persist, or to diversion of trade, the Union or the United Kingdom may unilaterally take appropriate safeguard measures.” Later: “The Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Mr Simon Coveney, says that the grace periods exist to give supermarkets in particular, the opportunity to readjust their supply chains to adapt to what he refers to as ‘these new realities’. I am afraid that confirms in the minds of many that the protocol is being used to create diversion of trade.” The amount is already formidable and will grow further when grace periods end.

Carla Lockhart pointed out that the claim that the Protocol is needed to support the Belfast Agreement is piffle. This was endorsed by Sir Iain Duncan Smith who went on to say that the Protocol was always seen as temporary and therefore capable of change: “That was made clear in every single article: article 184 of the withdrawal agreement, article 13 of the protocol and, importantly, paragraph 35 of the political declaration, which envisages an agreement superseding the protocol with alternative arrangements. The idea that this is somehow set in stone and we only have to work to make it better is an absurdity in itself.” He also had participated in the positive EU talks about mutual enforcement and commended that as the way forward.

Duncan Baker picked up on the comparison of Brussels' view that the Protocol must be implemented to the letter with that of Shylock in the Merchant of Venice. The UK needed the equivalent of Portia’s “not a drop of blood” to void the contract and allow justice to be restored and a fresh Protocol to be prepared to meet the needs of all parties. Unfortunately, as he acknowledged, using the EU’s rather tenuous grasp of whether Northern Ireland was an integral part of the UK, or merely part of its customs territory, was a bit thin in terms of voiding the Protocol. His proposals for its replacement had more substance. Brussels is not going to take the use of Article 16 seriously unless they can see a better alternative. For the purpose of these notes, I have labelled this the “feint” strategy: putting an acceptable alternative on the table or unilateral Article 16 if it is not seriously negotiated.

This is the key difference with the command paper: the EU will not negotiate until they want to do so. The first issue, therefore, is how the UK can bring that about. The diversion of trade is a far stronger “drop of blood” than the perceived status of Northern Ireland.

As the Northern Ireland ministers were too busy to attend, the Paymaster General, Penny Mordaunt, summed up on behalf of the government. She gave a fine impression of not having attended either.

The command paper route to resolving the Protocol problem is doomed. According to Saturday’s Telegraph, the PM wanted unilaterally to trigger Article 16 forthwith but was talked out of it. Just as well because with the UK’s current reputation as the bad guys and the case going to the European Court, the UK would certainly have lost in law despite the evidence. The UK must address its reputational issues. Ministers’ reluctance to listen either to the EU or advice from Parliament or to Irish politicians is contributing to the problem. The “feint” approach may work if Belfast and Dublin are allowed to work it up to a feasible solution likely to be acceptable to Brussels and London. The on-the-bed parents are far more likely to understand and accept the new baby than distant politicians who neither understand the true relationship nor have to live with the consequences.

Before we finish, there is one more option: “The Trojan Horse”. The EU has always said they would not renegotiate the Protocol, partly because it already has provisions within it for change and development. What that may mean is that they will object to having anything taken away but will discuss additions. It would be difficult to frame some UK wishes, e.g. removing it from the EU Court’s jurisdiction, in EU-speak, but they must learn to put proposals in ways with which Brussels should be comfortable. And that requires listening. For example, the EU Court of Justice could appoint a panel of three judges: a national from an EU member state, a UK citizen and a Swiss or other neutral agreed by the first two.

One of my first lessons at school was not to pick fights with boys bigger than me, especially not with those who did not like me. The perceived belligerence of its negotiators has helped neither the UK’s cause nor reputation. The UK should immediately mount a PR blitz across the EU, Washington, Boston and New York to show just how petty and ridiculous the EU is being. Archie Norman, Chairman of Marks and Spencer, has provided good examples such as the lorry driver being sent back, goods undelivered, just because of a sandwich he had in his cab for his lunch. 14 professional veterinarians are employed just to fill in forms. If the ink is the wrong colour, the forms are rejected. Modern digital systems cannot even be considered. The only concession to modernity is that the forms do not need to be completed using quills. The absolute priority now is, by using the nonsense inflicted on our people, to change general perceptions and the Brussels mood. Everyone loves a listener.

Sir Simon gives us the establishment view of British housing

Simon Jenkins tells us how things ought to be:

The reality is that English housing policy is still in the dark ages. Jenrick should be promoting downsizing, taxes to discourage under-occupation, the renovation of old building and increasing housing density in suburbia. There is no need to build on greenfield rather than brownfield land anywhere in Britain. Ministers seem to think the only “real” house is a car-dependent executive home in a southern meadow. It is, as Jenrick says, a “dream” – but that is not a need.

Ought to be from a disturbingly elitist position of course. The peasantry should live in smaller houses where the establishment damn well tells them to live.

Which is to miss the point of having an economy, a civilisation, at all. That point being not simply to meet human needs. Instead, it is to gain the maximum amount of those things which humans would like to have. The maximum possible amount that is, for of course there are limitations set by such inconvenient facts as physics, the level of technology, the availability of resources (we do live in a universe of scarce resources after all) and so on.

Britain faces no shortage of land upon which housing could be built. No shortage of land upon which substantial houses with decent sized gardens can be built. The only limitation faced is the permission to be able to build upon the extant land.

….it is hard to see a vision of southern England as anything but open to a creeping, Los Angeles-style urban sprawl. This means ending 50 years of the once-prized divide between Britain’s towns and their surrounding countryside.

Prized by whom Sir Simon? The very argument used to insist upon the planning restrictions is that this is what people want. We wouldn’t have laws preventing development if development wouldn’t happen without said laws. Therefore the existence of, the argument in favour of, the limitations is to prevent people gaining more of what they desire.

And why is it that public policy should be specifically designed to prevent people gaining more of what they desire - houses they’d like to live in built in places they’d like to live?

Well, unless you’re the sort of elitist who insists that the peasantry should just live in whatever hovels the establishment might permit them to have.

But, but, the National Health Service should be cheaper

There’s a certain logical problem with the never ending calls to spend more upon the National Health Service:

Yet there is no escaping the truth that, as with supermarket chicken or a new pair of trainers, we get the health service we are willing to pay for. A world-class health service cannot be sustained by claps alone.

It is no exaggeration to say I do not know a single doctor or nurse who believes that the NHS as we know it will survive much longer. We watch, resigned, despairing, as the electorate drifts — eyes wide shut — into a de facto two-tier system in which the NHS provides a limited rump of core and emergency services while the rest is rationed to oblivion unless you can pay.

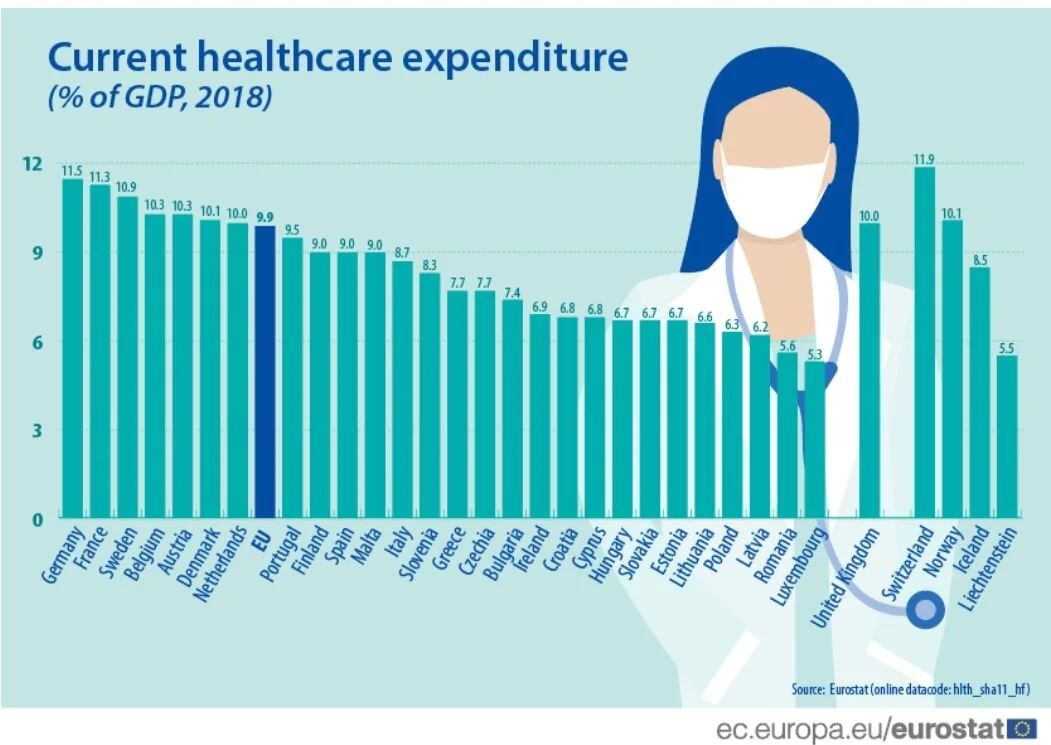

Perhaps more should be spent. Perhaps not. What we require is some method of working this out. The thing being that we do in fact spend just about bang on the European Union average on health care. So if our system is worse than those others then it’s not the money which is the issue - it’s the system, how it is run perhaps.

Yet we are also continually told that the NHS is a more efficient manner of running health care than other methods. By banishing that waste of competition and profits, leaving only that cooperation not mediated by money, we have a system which maximises output compared to input.

If that is true then the NHS should be cheaper than those other European systems. Either we should be gaining the same level of health care for less cash, or better for the same. If the organisational method is indeed more efficient. This not being what we are generally told of course, nor what is said when the NHS budget is discussed. That we should be spending less upon the NHS precisely because the NHS is so special and wondrous.

Or, perhaps, we might have a different answer. That the NHS is special and wondrous but not in a good way. That we already spend that European average and yet have health care that is not up to that average. In which case we should concentrate on the construct of the system, perhaps remove the manners in which the NHS is so special and wondrous.

No? Perhaps introduce a bit more of that competition that so many other systems use in order to attain that same performance and link between money in and health care output?

It doesn't matter what type of housing gets built - just build some housing already

Near all agree that Britain needs more housing. The arguments start over what type of housing, who should build it and what price should be charged for it. The truth is none of those subsidiary questions matter. Just get on and build the housing, however:

Increasing supply is frequently proposed as a solution to rising housing costs. However, there is little evidence on how new market-rate construction—which is typically expensive—affects the market for lower quality housing in the short run. I begin by using address history data to identify 52,000 residents of new multifamily buildings in large cities, their previous address, the current residents of those addresses, and so on. This sequence quickly adds lower-income neighborhoods, suggesting that strong migratory connections link the low-income market to new construction. Next, I combine the address histories with a simulation model to estimate that building 100 new market-rate units leads 45-70 and 17-39 people to move out of below-median and bottom-quintile income tracts, respectively, with almost all of the effect occurring within five years. This suggests that new construction reduces demand and loosens the housing market in low- and middle-income areas, even in the short run.

A reasonable logical surmise is that adding even expensive housing to the market increases supply. Rich folks go and occupy that new and expensive housing. The argument in favour of insisting upon those affordable units is that this is where the process stops. Which, of course, it doesn’t.

For those rich folks moving into that new and expensive housing have just vacated a place one step down the market. Which will be moved into by someone else - who has equally just vacated a place and so on.

This cascade down the market means that one new expensive dwelling creates an empty space at the cheapest end of the market. Which is exactly what everyone desires, isn’t it? More and cheaper housing at that bottom end of the market? Something which is, as above, supplied by simply building more houses.

The logical surmise turns out to have empirical support. So we can stop all of the micromanagement of who builds what, where, for which price. Simply build more housing of whatever type and allow the market to sort through the relative valuations. Possibly a simple enough plan for even British politics to be able to grasp it. Possibly…..

It's not that we've become entirely conspirazoid, not entirely

We note two pieces of news, one a day after the other:

Great Britain faces its greatest risk of blackouts for six years this winter as old coal plants and nuclear reactors shut down and energy demand rises as the economy emerges from Covid-19 restrictions.

National Grid’s electricity system operator, which is responsible for keeping the lights on, said it expected the country’s demand for electricity to return to normal levels this winter, and would be braced for “some tight periods”.

That planned transition from secure baseload to reliance upon variable renewables might not work all that wonderfully. Perhaps, that’s the word from the engineers who currently run the system. The other piece of news, from the day before:

The government plans to strip National Grid of its role keeping Great Britain’s lights on as part of a proposed “revolution’” in the electricity network driven by smart digital technologies.

The FTSE 100 company has played a role in managing the energy system of England, Scotland and Wales for more than 30 years (Northern Ireland has its own network). It is the electricity system operator, balancing supply and demand to ensure the electricity supply. But it will lose its place at the heart of the industry after government officials put forward plans to replace it with an independent “future system operator”.

The engineers who run the grid will be stripped of their responsibility to do so and be replaced by political appointees. Who, one must presume, will be more politically reliable than to insist that there might be problems with the planned change in the national electricity system.

We are not diving headlong into conspiracy theories here but we do think that it’s incumbent upon those proposing the change to assuage, even refute, such concerns.

Because it’s not exactly unknown in politics that bearers of bad news get replaced by those willing to affirm now, is it? Even if the affirmation doesn’t in fact coalesce around reality.

It’s possible that the correct response here is just for us to go and have a little lie down ad some deep breathing exercises. And yet, well, if there were things likely to go wrong what would the political reaction be? What is happening, no?

The real test is going to be who gets appointed to that “future systems operator” and if it’s the people we think it will be then deep breathing exercises just aren’t going to be enough.

Perhaps we shouldn't have social housing at all?

We think this is interesting:

A Labour MP defrauded her local council out of nearly £64,000 by “dishonestly” obtaining social housing over three years, a court heard.

Apsana Begum appeared at Snaresbrook Crown Court on Wednesday charged with three counts of fraud that allegedly took place over three separate periods between 2013 and 2016.

Ms Begum, who denies all charges,

We have no view on the case. However, the number claimed does interest - £64,000 is real money even by local council standards.

It’s a standard claim that social housing - and council housing even more so - makes a profit. There’s an excess of income over costs, this is a profit, right? Except that’s not true, this £64,000 number is correct. For this includes the opportunity costs - what else could have been done with these resources? Like, here, housing someone else perhaps. Or, in the more general case housing provided at less than market price clearly leaves money on the table - exactly that difference between market price and the rent actually being charged.

That is, the entire system of social, affordable, council, housing is wildly expensive. Our proof being the claim that three years’ worth of it has this value of £64,000. Meaning that it might well be better to not have said system at all. Instead, work to lower the cost of all housing by increasing the supply.

By, say, blowing up the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 and successors?

We’d also note that if said social housing has a value of £21,000 a year then don’t we have to rather change our estimations of the wealth distribution? For currently we assign value to equity in owner occupied housing and yet value that £21,000 a year as having no value to the recipient at all. It might not be worth, to that recipient, that much but it most certainly has a value and therefore a capital value.

What would Cuba have been without the revolution?

Given that we are seeing at least stirrings of the counterrevolution in Cuba it’s worth pondering what the place would have been without that revolution itself.

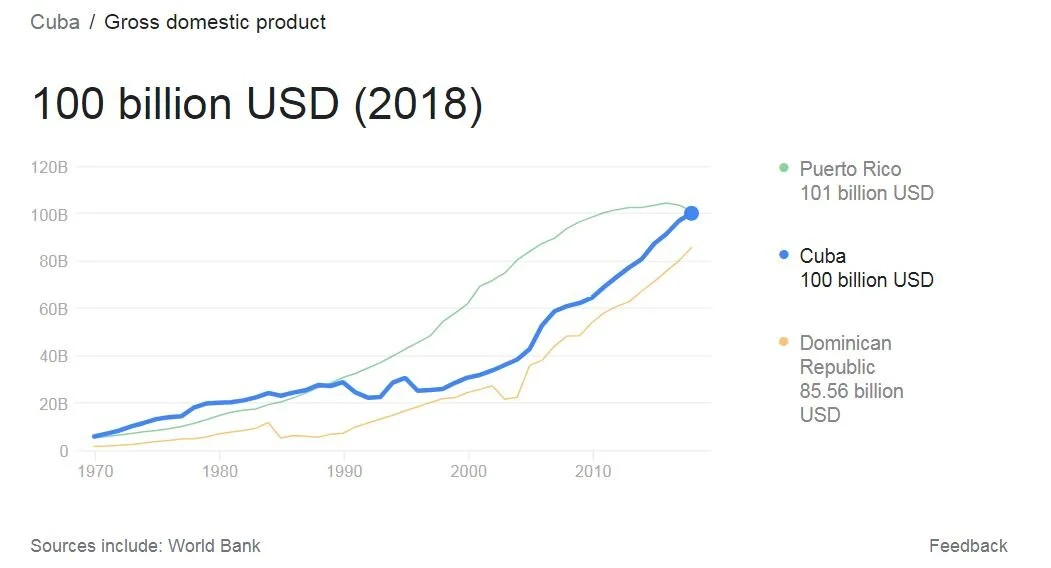

One problem we have is that the usual numbers we’re presented with are entirely and wholly unbelievable. The idea that Cuba’s GDP is $100 billion is absurd. The population is about the same as that of the Dominican Republic (GDP $88 billion) and it would indeed be insane to claim that living standards are higher in Cuba than that Republic. No one in Cuba outside the senior ranks of the Communist Party is living as if GDP per capita is approaching $9,000 a year so therefore GDP per capita isn’t approaching that - GDP is the value of all consumption in one of the calculation methods after all.

That isn’t usually the claim though. Rather, that while the socialist revolution hasn’t brought mass hyperconsumerism (to adopt the usual language) it has brought two much more valuable things. Free health care and freedom from the regional hegemon, the United States. Well, OK, so our counterfactual needs to be - by preference Spanish speaking just to reduce alternative possible influences - a Caribbean island that did remain subject to that hegemonic power of Uncle Sam.

Fortunately we have one of these to compare with - Puerto Rico. Where GDP per capita is, even at those unbelievable about Cuba official numbers, three to four times higher (about a quarter of the population with roughly the same total GDP). They also have free healthcare, or at least a system that provides it for free to those who cannot pay themselves. Just as we also have a system of free healthcare even though we didn’t have a bloody revolution and generations of penury to get it.

We do not argue that Puerto Rico is some nirvana, some perfection upon the Earth. We would argue that it’s a better outcome than that which Cuba suffers.

Or, more simply, as 1989 showed us, socialist revolutions don’t achieve their claimed goals let alone actually work. As with the Soviet one, after 70 years plus or minus some change the Cuban revolution has produced a result worse than not having that revolution. Even when we do consider the health care thing.

Here’s hoping that the people will soon be free of this dreadful error…..

This is to be on a hiding to nothing

It’s entirely reasonable - effective even - to demand that the world be different than it is. We do it ourselves all the time, demanding that greater liberty, more freedom and less government as we do. However, to demand that the world be different than it can be is to be on that proverbial hiding to nothing.

Politicians around the world have been promoting responses to the Covid-19 pandemic with statements such as: “we must open up”, “we have to learn to live with the virus”, and “freedom day”.

But to us epidemiologists these are almost meaningless political slogans that cover a vast array of possible scenarios, some of which are potentially very harmful, especially for the most vulnerable.

The approach of Boris Johnson’s government in the UK provides a particularly egregious example of how political rhetoric is damaging our ability to discuss pandemic responses in an open and transparent way. Framing our global response to Covid-19 with slogans starts to narrow the range of options in ways that may stifle thoughtful discussion of alternatives.

Things that are politically decided will be decided by politics. Which means the deployment of political rhetoric. That’s just how any such system will work because that’s how the mechanism being employed does work.

It will never be possible to have “scientific” decisions from the political system. Nor will it be possible to jury rig matters so that we do.

The very best that it is possible to do is to get government out of the decision cycle upon scientific matters thereby allowing the room for science to take place.

No, we do not therefore mean that there should have been no political decisions about Covid. Given those events there clearly was going to be more than the one political decision - to do nothing would have been one of those, as would doing anything. The point is, rather, that once something has been subsumed into the political decision making process then it is politics - along with that rhetoric - which will make the decisions.

Our favourite example of this is the, possibly apocryphal, story of Jim Callaghan and the steel plants. The science, the business logic, insisted that the British steel industry needed to be operating at scale. There are economies of such in this industry. So much so that the UK could only have a usefully effective steel industry if it had the one large and fully integrated plant. This logic was accepted in what was at the time a nationalised industry.

At which point half the single integrated plant was allocated to Wales and half to Scotland. For, obviously, political reasons.

Anything run by politics will be run by politics - why is that so hard to grasp?

Would anyone daft enough to want to be CEO of the NHS be up to the job?

The new Health and Care Bill is a veritable curate’s egg. We do need to link the NHS and social care to achieve a smooth transition between the two. We do need to remove the close to a decade old burdensome bureaucracy when outsourcing work to the private sector. We do need to remove the ambiguity of NHS England; as a Non-Departmental Public Body it is both answerable and not answerable to the Secretary of State at the same time.

It should either become an independent public corporation, like the Bank of England, or an Executive Agency which would be a separate organisation within the Department of Health and Social Care. NHS England staff would become civil, rather than public, servants. Given that “the Bill also includes proposals from the February 2021 White Paper to give the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care powers to direct NHS England”, it appears the Executive Agency option is being taken. It would have been sensible for the Bill to say so.

The addition to the powers of the Secretary of State, however, is a worrying feature of the Bill. According to the Commons Library briefing (p.8) the Health Foundation, NHS Providers and the NHS Confederation have all expressed concerns on that score. No ground rules are set for when the Secretary of State can move in to direct NHS England matters. The House of Lords may also be concerned with Clause 130 which “gives the Secretary of State some general regulation making powers consequential on the Bill. In particular, the power may be used to amend, repeal, revoke or otherwise modify any provision within this Bill or any provision made by or under primary legislation passed or made either before this Act is passed or later in the same Parliamentary session.” The worry is that a politician playing to the media may conflict with a CEO trying to run the NHS the country needs.

The Bill is a curious mixture of strategy and technical detail with some of the most important strategic issues omitted altogether. For example, there is no word on how the chronic shortage of doctors, nurses and care workers will be corrected. This problem has been exacerbated by the pandemic backlog and new immigration controls. Too many, maybe all, of the changes lack precision or justification in the explanatory notes. Integrating health and social care would be fine if the long-awaited social care Green (or White) Paper had appeared and given us any idea on what social care will look like. The Nuffield Trust put it this way “the hope that the NHS will cooperate more with social care services will also come to nothing without proper reform so that more people receive help, more staff join the sector, and stability is restored after years of desperation.”

42 Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) now cover England but they have grown like Topsy, each in it’s own way with no standard pattern. “As a result, there are significant differences in the size of systems and the arrangements they have put in place, as well as wide variation in the maturity of partnership working across systems.” Whilst the objective of a joined-up health care interface is incontestable, they involve a plethora of meetings. Taking GPs away from dealing with patients, as the 2012 Act did, may help some patients but harm others.

The boundaries for ICS responsibilities vary; some include housing, some do not. In short, we have no idea, and nor does the DHSC, which ISC models are better than others? Devolution has its merits but the Bill should define what will be devolved to ICSs and what will not be. Nor is the national versus local logic trap addressed. ICSs move decision-making, e.g. on how budgets are spent, from national to local. Tailoring the provision to local needs makes sense but it also means that some benefits with be available in some localities but not others, at which point the tabloids will cry “post-code lottery”. What is the answer?

The Bill sets a very broad remit for NHS England, namely the “Triple Aim” of “better health and wellbeing, better quality health care and ensuring financial sustainability”. No one will argue with the NHS living within its means, topped up in time of emergency. If the NHS is really responsible for our individual health, rather than us, the government should adopt the Chinese model and resource the NHS when we are fit and not when we are sick. If the aim refers to public health in general, why should the NHS do that when we have a plethora of other public health bodies at national and local government levels?

“Well-being” should only be a matter for the NHS when we are ill or at risk of becoming ill. The dictionary defines well-being as good spiritual and human relationships, having a (financially) comfortable way of life and being happy. That’s a tall order for the NHS. “Better quality health care” is not just a matter for the NHS: it is a matter for the ICSs.

With the cost of the NHS soaring to heights that will become unaffordable, we should be thinking about trimming, not adding, responsibilities. Should it simply be concerned with the treatment and cure of physical and mental health conditions, i.e. the sick, or should it be responsible for wider user demands, e.g. fertility and cosmetic surgery? Or for primary research, and reduce over-treatment of the dying, tonsillectomies, over-prescription of antibiotics and over-testing?The Taxpayers Alliance reported one Foundation Trust spending £360,000 on a failed music festival, No doubt it would have been good for the wellbeing of the citizens of Derby.

Hospital Foundation Trusts, with their layers of governance, are both independent and not independent of the NHS and DHSC at the same time. In 2003, NHS Foundation Trusts were “established in law as new legally independent organisations called Public Benefit Corporations.” The Boards were to “be made up of local people, patients and carers and staff.” Has anyone investigated whether this local democracy is worthwhile or whether it just distracts the CEOs from running their hospitals? The 2012 Act encouraged all Hospital Trusts to shift to Foundation status but one third have not done so. The current Bill affirms all this, stopping NHS England from limiting Foundation Trust capital, but not revenue, spending if NHS England thinks the Foundation Trust is about to spend more than its fair share of ICS capital money.

Many of the changes in this long and complex Bill are to be applauded, notably those which tidy up the 2012 Act. No doubt there will be another before long as a future Secretary of State makes his mark. As one wit put it “What changes all the time but stays the same? The NHS.” The central issue of this Bill is the redistribution of responsibility. We all know who will take the credit or blame when things go right or wrong. Do we really want a politician, without relevant experience and changing with every reshuffle and election, to direct NHS England rather than a seasoned executive from that sector?

Now look at it with the perspective of an incoming CEO once this Bill is enacted. On paper, one has charge of the largest organisation in the UK, 1.5M people, and the fifth largest in the world. As the staff are now civil servants, you do not set the wages nor even negotiate them. The 2019/20 NHS England budget was £139 billion and the Trusts, mostly Foundation Trusts, had £92 billion of that. But they do not report to you. GPs’ surgeries cost about £13 billion, and probably should be double that, but GPs do not report to you either. The only parts of NHS England that do report to you are the parts that do not actually treat or cure people.

The DHSC has 14 arm’s length bodies apart from NHS England, though they come and go so fast it is hard to keep track. The new Bill gives powers to the Secretary of State to change any of them whenever, but that is probably a good idea. Nowadays, IT is an integral part of any large organisation with the rare exception of NHS England. NHS Digital and NHS Business Services are separate arm’s length bodies reporting directly to the Secretary of State. No wonder major NHS IT initiatives have such a chequered history. Social care has no arm’s length bodies at all. These bodies will all keep the Secretary of State well versed on the NHS matters he can micro-manage, even when the media are quiet. ICSs will be taking care of dealing with all the people who actually need health care and they will be run by hospital Trusts, GPs and local authorities, none of whom answer to the NHS CEO. Overruled and unsupported, one has to question the wisdom of anyone who wants the job.

Well, if you're going to be wholly ignorant about it....

At least 21 - yes, count ‘em, 21! (over 20 is at least 21, no?) - politicians have signed up to be rulers of the world. Sorry, that’s not quite right, have demanded the power to create a Global Green New Deal in which all our lives are lived according to their precepts.

One of whom tells us this concerning what must be done:

Manon Aubry, a French MEP, said governments must focus on social justice and the climate. “As the consequences of the climate crisis become more and more alarming, inequalities are growing and the poorest are hit hardest by the impacts of a changing climate. If we want fair, systematic and effective climate policies, we need a radical shift away from free trade and free-market ideology.”

It’s OK, we do grasp that some people just don’t like trade. Who are these filthy foreigners who do things better than our own folks at home? And why should they be allowed to? Poujadism has not been entirely unknown in France in the past after all.

We are also aware of Polanyi and his insistence that it is the local web of personal interaction which gives meaning to economic life. We disagree but accept that some don’t.

Opposition to free trade can thus run on that spectrum from rampant xenophobia to a principled moral stance, however wrong either or both might be.

However, the one thing that isn’t going to work is killing trade to beat climate change. This was tested in the economic models which underpin all discussions of climate change, the SRES (and still do underpin, the RCP and so on models are all derived from the same place). Whatever our views on free markets red in tooth and claw - as opposed to a more comfy social democracy - it’s an explicit insistence in those models that a more globalised, free trading, world produces a better outcome than a more regionalised and fragmented one.

In the jargon, A1 is better than A2, B1 better than B2. A standing, roughly, for free market capitalism, B for something more kumbaya. But 1 for that globalised and trading world, 2 for one less so than we currently have.

The better being defined by fewer and richer people, which is nice enough. But more importantly for the argument here, with less climate change because lower emissions.

The why should be easy enough to understand. Trade just means that things are done where it is most efficient to do them. Therefore, for any level of living standard to be enjoyed by a population of whatever size, trade will lead to the use of fewer resources to achieve that economic wealth. Or, the same statement moved around a bit, for any given level of resource use the living standard to be enjoyed will be higher.

Trade means, holding other things equal, less climate change. Therefore the one thing we don’t want to do as part of our actions against climate change is to restrict trade.

As Ms. Aubry is entirely ignorant of this obvious point then we’ve not got to pay much more attention to her demands to rule the world, do we? Well, other than to just reject the idea as being ludicrous. But then Caroline Lucas is involved so that last point should be obvious anyway.