A significant error in Ed Miliband's demands about climate change

Leave aside the more general background concerning climate change and consider just this point from Ed Miliband:

This is not simply failing to protect us from the biggest long-term threat we face; it’s economically illiterate too.

The case for investing now is not just clear as a question of intergenerational equity, it’s also the only conclusion to draw from a hard-headed fiscal analysis of the costs and benefits. The Office for Budget Responsibility tells us that the costs of acting early are surprisingly small relative to our national income – in the central scenario, an average annual investment in net terms of just 0.4% of GDP between now and 2050.

Meanwhile, we know that inaction is entirely unaffordable, leaving massive costs of climate damage racked up and left for future generations.

This assertion is wrong because it’s economically illiterate.

It’s assuming static technology and the truth is that we live in a world where technology - and the prices for the different variations of it - changes.

Again, stay within the logical structure Miliband is using. There are costs in the future to climate change. There are costs today to avoiding that future. If technology - and therefore those avoidance costs - is static then yes, it could be true that action now is desired. But if technology is changing then this equation changes. It is possible - possible only - that the reduction in costs of the avoidance by delaying a year is greater than the damages from the delay as the price of the necessary technologies declines in that year.

For example, it is said that the costs of solar power decline by 20% a year. Alternatively that they have declined by 80% in this past decade. Well, OK, so imagine that we’d carpeted the country with solar panels a decade ago or waited until now to do so. The cost of the move to solar power would be 80% lower through that decade of delay. The costs of the damages in the future through that delay would be?

We do in fact know, or at least can estimate, those climate damage costs of delay. A decade back solar power was not price competitive even adding the social cost of carbon to the fossil fuel alternatives. This is why those amazingly high feed in tariffs. Therefore the gain from the delay caused price reductions is greater than the costs from said delay.

The point here is the logical one, that doing everything now is necessary - or even desirable - just is not true. The prices of those fossil fuel alternatives are changing. Therefore the optimal amount of them is changing too. We’ve even a very large report explaining all of this in detail, the Stern Review. The very place that Mr. Miliband oft claims to gain his proof for the necessity of action from. We suggest he goes read it again with perhaps more attention to detail this time.

Does the spread of mobile phones indicate a rising need for personal communications?

To ask that question is to betray a certain Forrest Gump-like innocence. For clearly that’s not what has happened. Instead we’ve found - or developed - a new technology to meet an extant human desire or need. That is, the spread of an activity, or manner of achieving something, can be because of one of those technological developments rather than any change in human desires. Therefore proof of the spread cannot be taken as an increase in the need:

A decade ago, the emergence of mass food banks in the UK could genuinely be described as shocking. The image of families queueing in their local church for a box filled with pasta and beans has not only since been normalised, it has spread.

This does not simply mean the number of food banks has grown in recent years – there are now more than 1,300 such places in the Trussell Trust’s network, compared to fewer than 100 in 2010, as well as hundreds more independent ones – but also that these have opened the door for other types of donation centres, each set up by community groups and charities in response to growing need.

Food banks are a technology, for all methods of organising something are a technology. They arrived in Britain after the turn of the century. It is not logically sound to assume, or as above insist, that the spread is due to increasing need. It could be, note could be, that we are now able to meet an extant need or desire.

Which is what we think it is. One advantage of that increasing speed toward the grave is that memories and experience are long enough to recall what it used to be like. The British welfare system always did have holes in it. Payments sometimes did get delayed - we directly and specifically recall an 8 week wait for unemployment benefits that happened to one acquaintance.

That is, food banks are a solution to the efficiencies of the state run welfare state. At which point the insistence that they must be nationalised seems more than a little odd. Why would we want to put the solution into the hands of those who caused the original problem?

So, just what is ethical fashion then?

The Guardian tells us that cheap, or fast, fashion is unethical. The reason being that those working in the factories are making less than some think they should be making. This strikes us as being remarkably obtuse about ethics.

We bow to no one in our insistence that of course the consumer should express their preferences. If a label claiming “sustainability” or “ethical” adds to utility maximisation then not only go for it if you wish to, you should go for it. And yet:

In 1970, for example, the average British household spent 7% of its annual income on clothing. This had fallen to 5.9% by 2020. Even though we are spending less proportionally, we tend to own more clothes. According to the UN, the average consumer buys 60% more pieces of clothing – with half the lifespan – than they did 15 years ago. Meanwhile, fashion is getting cheaper

Clearly this process is making us, us here, richer. We are gaining more - much more - for a smaller portion of our income. Clothing poverty was, after all, a real thing. “Sunday best” is now just a phrase and one that we expect to drop out of the language as the actual experience - of having just the two sets of clothes, workaday and that Sunday set - rolls on to being a century and more old.

We’d also essay a supposition. Those collarless shirts that have been so popular these past few years. An older phrase for them is “grandad shirts” when shirts were made with detachable collars. So that one could wear the same shirt for several days but with a clean collar each one. A generation before that there were also detachable cuffs. Both shirts and the washing of them were expensive. Or read old novels, the phrase “fresh shirt” and the putting on of it. No one writing now would emphasise that for it’s assumed rather than the event it used to be.

So, our experience is better. What about those factory workers?

Their research suggested that the textile factory in Izmir received just €1.53 for cutting the material, sewing, packing and attaching the labels, with €1.10 of that being paid to the garment workers for the 30-minute job of putting the hoodie together. The report concluded that workers could not have received anything like a living wage, which the Clean Clothes Campaign defined, at the time the report was released, as a gross hourly wage of €6.19.

The Clean Clothes Campaign has some very odd ideas about what a living wage is. In Turkey they seem to think that it’s 120% or so of the average national wage. Well, OK, maybe that is the income required to gain the lifestyle that the campaign thinks all should live at. It rather becomes an ethical question as to how to get there, doesn’t it?

At which point, Paul Krugman:

.... the wages earned in one industry are largely determined by the wages similar workers are earning in other industries....(...)...Second, the link between productivity and wages is thoroughly misunderstood. Non-economists typically think that wages should reflect productivity at the level of the individual company. So if Xerox manages to increase its productivity 20 percent, it should raise the wages it pays by the same amount; if overall manufacturing productivity has risen 30 percent, the real wages of manufacturing workers should have risen 30 percent, even if service productivity has been stagnant; if this doesn't happen, it is a sign that something has gone wrong...(...)...It is a fact that some Bangladeshi apparel factories manage to achieve labor productivity close to half those of comparable installations in the United States, although overall Bangladeshi manufacturing productivity is probably only about 5 percent of the US level. Non-economists find it extremely disturbing and puzzling that wages in those productive factories are only 10 percent of US standards.

Those numbers are a little old but the points still stand. Wage rates are set across an economy, not by individual factory. Krugman again:

But matters are not that simple, and the moral lines are not that clear. In fact, let me make a counter-accusation: The lofty moral tone of the opponents of globalization is possible only because they have chosen not to think their position through. While fat-cat capitalists might benefit from globalization, the biggest beneficiaries are, yes, Third World workers.

Those textile factory jobs are better than a life staring at the south end of a north moving water buffalo. Which is why people voluntarily take them. This biggest advertisement for the process being Bangladesh, the country most reliant upon the schmutter trade. Yes, wage rates are low by our standards. They’re also double what they were a decade back and quadruple those of the turn of the century. As one of us put it in somewhat salty fashion, this does actually work as a method of reducing poverty.

Those Third Worlders are becoming less mired in destitution. We benefit too. Perhaps that second shouldn’t matter ethically but it is the vital ingredient that makes the process self-supporting. That we gain is the feedback that keeps the development cycle going.

Which gives us two very different possible ethical approaches. To purchase less but more expensively, thereby paying those living wages to whatever small number of people is required to produce that restricted consumption. Or, when passing that shop of £1 t-shirts, looking at that screen of 50 pence bikinis, buying the second and the third selection because why not aid the poor?

We insist that the ethical choice here is the hyperconsumption of fast fashion. As we’ve been known to remark, ethics require that we buy those things made by poor people in poor countries. For who wouldn’t - or perhaps who shouldn’t - prefer to make entire countries rich?

The next billionaires

Most of us have taken on board the coming reality that will involve such technologies as self-driving electric cars, people-carrying drones, lab-grown meats and artificial intelligence, and we fully expect that some people in the forefront of these developments will become billionaires, if they are not already. It is worthwhile, however, to look beyond these innovations to speculate what might be the next breakthroughs that could generate a subsequent crop of billionaires.

One approach is to look at the problems that afflict some people’s lives, and which they would happily pay to resolve, or which others might pay for on their behalf. Malaria, for example, kills an estimated million people each year, a majority of them being children under five years old. Its fatalities have been reduced by the spread of insecticide-impregnated mosquito nets, and promising experiments have been conducted using mosquitos genetically-modified to kill the plasmodium parasite. The real breakthrough, though, will be a vaccine that makes people resistant to it. The team that develops one could become very rich because this is something that the world will pay for. And Nobel prizes would be an added bonus.

Worldwide obesity is a problem awaiting a solution. Governments have tried behaviour changes such as sugar taxes and advertising bans on so-called junk foods, but these do not seem very effective. There will be huge rewards if someone can come up with a non-surgical medical solution, perhaps a treatment that alters the body’s response to food, or a medication that changes the metabolic rate.

Dementia has become a progressively more serious problem as people’s life expectancy has increased, and has huge resulting financial as well as emotional costs. If anyone can develop an effective treatment to prevent and reverse the degenerative process, it would be a huge commercial success as well as a boon to humanity.

A less destructive problem is male pattern baldness. Men might accept its inevitability, but no-one likes it. Present transplant technology is invasive, and there might be a solution by growing hairs in lab dishes from modified cells and inserting them to fill the bare patches. Even better would be a treatment that persuades the body’s own cells to grow hairs in the places required. Men the world over would pay to retain or regrow their youthful hair.

Many people would prefer to stay younger-looking for longer in life, and people pay fortunes for cosmetic treatments that postpone the appearance of age. They would pay for a medical treatment that achieved this, perhaps by lengthening the telomeres, perhaps by CRISPR technology. Fortunes will be made when this is achieved.

The pandemic has led to great strides being made in the understanding of how viruses work, and it is entirely possible that there might finally be the elusive cure for the common cold. It might be that as strains are identified each year, a vaccine could be administered alongside the annual flu vaccine (and possibly now the annual covid vaccine) that will give immunity for most recipients to the common cold as well.

Allergies can blight the lives of those afflicted by them, including pollen allergies such as hay fever. Present treatments work to suppress the symptoms in some people, but what is really needed is a process that can make people resistant. It might be done using nano gene technology of the type now being used to target certain cancer cells.

On a lighter note, there are riches to be gained for someone who develops an instant hangover cure. It might be a pill left at the bedside table before a night out that would prevent a hangover emerging in the morning, or it might be one taken in the morning that delivers recovery within minutes. Again, this could be a business worth billions.

Midges, the little biting insects that blight the West of Scotland’s summers, cost the Scottish economy billions of pounds in lost tourist income as potential visitors are deterred. If a biological process could be developed to extirpate them, it would be a major boon to the local inhabitants as well as to the economy. Some environmentalists might object, but the niche occupied by the pests would soon be filled by less offensive insects.

Terrorism will remain a problem as long as there are terrorists, and there are possible avenues that might lead to technological ways of combating it. It might be possible in principle to develop a type of radiation that could prematurely detonate explosives, including bullets, within its range. It might even be possible to detect the subtle changes in the brain that take place when someone goes down the route of extremist fanaticism. Since these will probably be developed, if at all, by military establishments, neither of these are likely to make people rich.

It would be good for the country if these, barring the last one, could be developed in the UK, and government could play a role by making such initiatives easier to undertake, to attract investment funding, and made more rewarding to those who put in the effort and take the risks of developing them.

How the justification changes in only a generation or two

Apparently it’s necessary to abolish capitalism in order to beat climate change:

Alas, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

...(...)...

... it’s the obsession with economic growth at any cost.

This is, of course, untrue. As the basic analysis underlying all climate change murmuring insists - and yes, this underpins Nordhaus and his Nobel, the Stern Review, the IPCC, COP this and that, all of it - beating climate change is entirely consistent with the continued existence of capitalism. Indeed, given that the task is to foster technological change then that mixture of capitalism and free markets is exactly what is required, for that’s the system which best fosters technological change.

It’s also untrue that capitalism - or markets for that matter - demands economic growth at any cost. It’s an efficient manner of gaining that growth, true, but the growth itself is something more generally desired. Humans do like economic growth. After all, few of us like the abject poverty which is the alternative.

But here’s the bit we find fascinating. A generation and two back that socialism that is touted as the alternative to capitalism was so touted on the basis that it was more efficient. That scientific planning, scientific socialism, would produce more growth than that horrible wastefulness of capitalism and market competition. This was the argument for both the horrors of the Soviet system and the dreary boredom of post-WWII nationalisations alike. More growth through socialism.

Well, that didn’t work out well. So now the argument is that we must have socialism in order not to have growth. At which point the argument can be seen to be as threadbare as it actually is. If the answer is still that we must have socialism but the reason why has reversed polarity then clearly we’re in the grip of a religious mania, not a logical analysis. It’s now as with the insistence that yes, but you didn’t put enough virgins into the volcano.

New technologies and the sorting process of the market

Andrew Orlowski points out that Artificial Intelligence is not, in fact, all that good.

For years policymakers have believed that machine learning – the foundation of the current wave of AI hype – is fundamental to advances in robotics that will herald a “Fourth Industrial Revolution” – but the two don’t really go well together at all, or at least not using currently fashionable methods.

“Data-hungry, idealised algorithms simply fail,” leading researcher Filip Piękniewski told me. “The reality is we don’t know how to build control systems for machines that would be anywhere as robust as our own brains but we just love to fool ourselves into thinking we can do that,” The veteran robotics expert and former head of MIT’s AI lab Rodney Brooks was even more scathing about OpenAI’s defence that the “market wasn’t ready” for such wonders as the Cube-dropping Cube solver. “Perhaps the ‘problem’ is that the market is mature and understands what is valuable and not.”

The logical suggestion then follows, perhaps politicians should stop investing in or directing AI in the search for a Hail Mary Pass around current problems.

This does not mean we should all be ignoring AI of course. It just means that we’ve already got a method of sorting through the varied claims - the market.

A new technology, whatever it is, will work on some human problems and not on others. The Grand Task is to sort through those problems we wish to solve, test whether this new tech aids or not, then kill off the failures and do more of the successes. Which is exactly what free market capitalism does - it is, rather, the saving grace of the system. It also contains its own feedback loops - profit is the signal that a problem is being solved, as people wish to have it solved, losses are the signifier of a dead end.

Thus it is exactly when a new technology appears over the horizon that we must use that free market capitalism to test it. As, for example, the financial markets have been. High Frequency Trading, or perhaps arbitrage using algorithms to the extent the two differ, is exactly that AI. Crunch the numbers, read the patterns and without knowing anything about why they are trading upon the back of the pattern recognition. This works, even to the point that the original excess profits have now been competed down to perhaps below the cost of capital. All we’re left with is more efficient capital markets which are cheaper for the retail investor to use.

Shame, eh?

Or, as we’ve pointed out before, it’s exactly when we don’t know that we need to use markets to find out.

Irish Protocol: Why can’t the Government Listen?

Three routes to resolving the Irish Protocol crisis are considered: last week’s government command paper, “feint” and “The Trojan Horse”. The command paper is well written and sets out the way the Government thinks the Protocol should have been written, as well as some of the reasons why it was not. The future use of Article 16 is flagged. The trouble is that the EU rather likes the Protocol the way it is: the UK is being penalized for Brexit, the Republic of Ireland is benefiting from trade diverted from Great Britain and it all moves Northern Ireland closer to merger with the Republic, as the latter, and now the EU, have long sought.

Unsurprisingly, the EU immediately responded in the same way it has greeted all previous suggestions for re-negotiation: “no”. Triggering Article 16 and some blathering about it being nicer if we all got along better apart, the paper gave no reason for the EU to wish to re-negotiate. That is either Einstein’s definition of insanity or ministers are just not listening.

On 15th July, the Commons held an important debate on the Protocol. Some excellent and constructive suggestions were made, two were the diversion of trade from Great Britain to the Republic of Ireland (which contravenes the protocol) and the “manageable alternative” suggested by Lord Trimble writing in the Times on June 10th: under the heading “EU intransigence threatens the Good Friday Agreement”. As one of its two authors, he should know what he is talking about. He went on to write “A couple of years ago I had a meeting with Michel Barnier in which mutual enforcement of trade rules by the UK and the EU was discussed.” He said this suggestion had been well received by the EU but maybe the UK government was not listening.

Sir Bernard Jenkin opened the debate and drew attention, inter alia, to the diversion of trade. He said “article 16 states: ‘If the application of this Protocol leads to serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties that are liable to persist, or to diversion of trade, the Union or the United Kingdom may unilaterally take appropriate safeguard measures.” Later: “The Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Mr Simon Coveney, says that the grace periods exist to give supermarkets in particular, the opportunity to readjust their supply chains to adapt to what he refers to as ‘these new realities’. I am afraid that confirms in the minds of many that the protocol is being used to create diversion of trade.” The amount is already formidable and will grow further when grace periods end.

Carla Lockhart pointed out that the claim that the Protocol is needed to support the Belfast Agreement is piffle. This was endorsed by Sir Iain Duncan Smith who went on to say that the Protocol was always seen as temporary and therefore capable of change: “That was made clear in every single article: article 184 of the withdrawal agreement, article 13 of the protocol and, importantly, paragraph 35 of the political declaration, which envisages an agreement superseding the protocol with alternative arrangements. The idea that this is somehow set in stone and we only have to work to make it better is an absurdity in itself.” He also had participated in the positive EU talks about mutual enforcement and commended that as the way forward.

Duncan Baker picked up on the comparison of Brussels' view that the Protocol must be implemented to the letter with that of Shylock in the Merchant of Venice. The UK needed the equivalent of Portia’s “not a drop of blood” to void the contract and allow justice to be restored and a fresh Protocol to be prepared to meet the needs of all parties. Unfortunately, as he acknowledged, using the EU’s rather tenuous grasp of whether Northern Ireland was an integral part of the UK, or merely part of its customs territory, was a bit thin in terms of voiding the Protocol. His proposals for its replacement had more substance. Brussels is not going to take the use of Article 16 seriously unless they can see a better alternative. For the purpose of these notes, I have labelled this the “feint” strategy: putting an acceptable alternative on the table or unilateral Article 16 if it is not seriously negotiated.

This is the key difference with the command paper: the EU will not negotiate until they want to do so. The first issue, therefore, is how the UK can bring that about. The diversion of trade is a far stronger “drop of blood” than the perceived status of Northern Ireland.

As the Northern Ireland ministers were too busy to attend, the Paymaster General, Penny Mordaunt, summed up on behalf of the government. She gave a fine impression of not having attended either.

The command paper route to resolving the Protocol problem is doomed. According to Saturday’s Telegraph, the PM wanted unilaterally to trigger Article 16 forthwith but was talked out of it. Just as well because with the UK’s current reputation as the bad guys and the case going to the European Court, the UK would certainly have lost in law despite the evidence. The UK must address its reputational issues. Ministers’ reluctance to listen either to the EU or advice from Parliament or to Irish politicians is contributing to the problem. The “feint” approach may work if Belfast and Dublin are allowed to work it up to a feasible solution likely to be acceptable to Brussels and London. The on-the-bed parents are far more likely to understand and accept the new baby than distant politicians who neither understand the true relationship nor have to live with the consequences.

Before we finish, there is one more option: “The Trojan Horse”. The EU has always said they would not renegotiate the Protocol, partly because it already has provisions within it for change and development. What that may mean is that they will object to having anything taken away but will discuss additions. It would be difficult to frame some UK wishes, e.g. removing it from the EU Court’s jurisdiction, in EU-speak, but they must learn to put proposals in ways with which Brussels should be comfortable. And that requires listening. For example, the EU Court of Justice could appoint a panel of three judges: a national from an EU member state, a UK citizen and a Swiss or other neutral agreed by the first two.

One of my first lessons at school was not to pick fights with boys bigger than me, especially not with those who did not like me. The perceived belligerence of its negotiators has helped neither the UK’s cause nor reputation. The UK should immediately mount a PR blitz across the EU, Washington, Boston and New York to show just how petty and ridiculous the EU is being. Archie Norman, Chairman of Marks and Spencer, has provided good examples such as the lorry driver being sent back, goods undelivered, just because of a sandwich he had in his cab for his lunch. 14 professional veterinarians are employed just to fill in forms. If the ink is the wrong colour, the forms are rejected. Modern digital systems cannot even be considered. The only concession to modernity is that the forms do not need to be completed using quills. The absolute priority now is, by using the nonsense inflicted on our people, to change general perceptions and the Brussels mood. Everyone loves a listener.

Sir Simon gives us the establishment view of British housing

Simon Jenkins tells us how things ought to be:

The reality is that English housing policy is still in the dark ages. Jenrick should be promoting downsizing, taxes to discourage under-occupation, the renovation of old building and increasing housing density in suburbia. There is no need to build on greenfield rather than brownfield land anywhere in Britain. Ministers seem to think the only “real” house is a car-dependent executive home in a southern meadow. It is, as Jenrick says, a “dream” – but that is not a need.

Ought to be from a disturbingly elitist position of course. The peasantry should live in smaller houses where the establishment damn well tells them to live.

Which is to miss the point of having an economy, a civilisation, at all. That point being not simply to meet human needs. Instead, it is to gain the maximum amount of those things which humans would like to have. The maximum possible amount that is, for of course there are limitations set by such inconvenient facts as physics, the level of technology, the availability of resources (we do live in a universe of scarce resources after all) and so on.

Britain faces no shortage of land upon which housing could be built. No shortage of land upon which substantial houses with decent sized gardens can be built. The only limitation faced is the permission to be able to build upon the extant land.

….it is hard to see a vision of southern England as anything but open to a creeping, Los Angeles-style urban sprawl. This means ending 50 years of the once-prized divide between Britain’s towns and their surrounding countryside.

Prized by whom Sir Simon? The very argument used to insist upon the planning restrictions is that this is what people want. We wouldn’t have laws preventing development if development wouldn’t happen without said laws. Therefore the existence of, the argument in favour of, the limitations is to prevent people gaining more of what they desire.

And why is it that public policy should be specifically designed to prevent people gaining more of what they desire - houses they’d like to live in built in places they’d like to live?

Well, unless you’re the sort of elitist who insists that the peasantry should just live in whatever hovels the establishment might permit them to have.

But, but, the National Health Service should be cheaper

There’s a certain logical problem with the never ending calls to spend more upon the National Health Service:

Yet there is no escaping the truth that, as with supermarket chicken or a new pair of trainers, we get the health service we are willing to pay for. A world-class health service cannot be sustained by claps alone.

It is no exaggeration to say I do not know a single doctor or nurse who believes that the NHS as we know it will survive much longer. We watch, resigned, despairing, as the electorate drifts — eyes wide shut — into a de facto two-tier system in which the NHS provides a limited rump of core and emergency services while the rest is rationed to oblivion unless you can pay.

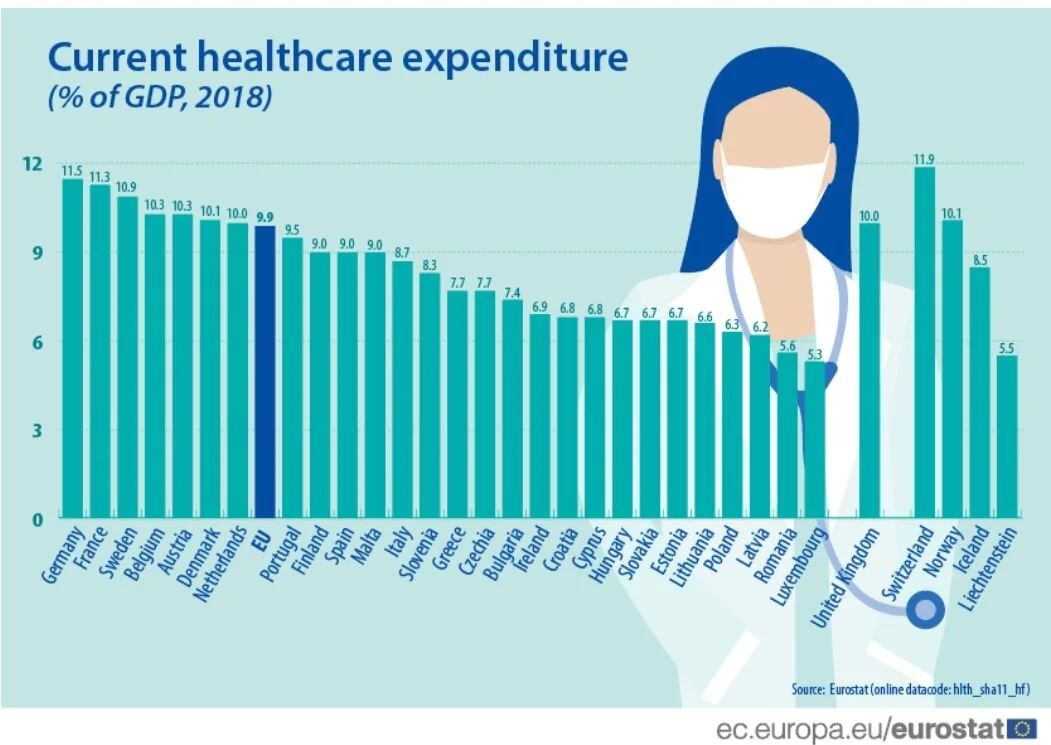

Perhaps more should be spent. Perhaps not. What we require is some method of working this out. The thing being that we do in fact spend just about bang on the European Union average on health care. So if our system is worse than those others then it’s not the money which is the issue - it’s the system, how it is run perhaps.

Yet we are also continually told that the NHS is a more efficient manner of running health care than other methods. By banishing that waste of competition and profits, leaving only that cooperation not mediated by money, we have a system which maximises output compared to input.

If that is true then the NHS should be cheaper than those other European systems. Either we should be gaining the same level of health care for less cash, or better for the same. If the organisational method is indeed more efficient. This not being what we are generally told of course, nor what is said when the NHS budget is discussed. That we should be spending less upon the NHS precisely because the NHS is so special and wondrous.

Or, perhaps, we might have a different answer. That the NHS is special and wondrous but not in a good way. That we already spend that European average and yet have health care that is not up to that average. In which case we should concentrate on the construct of the system, perhaps remove the manners in which the NHS is so special and wondrous.

No? Perhaps introduce a bit more of that competition that so many other systems use in order to attain that same performance and link between money in and health care output?

It doesn't matter what type of housing gets built - just build some housing already

Near all agree that Britain needs more housing. The arguments start over what type of housing, who should build it and what price should be charged for it. The truth is none of those subsidiary questions matter. Just get on and build the housing, however:

Increasing supply is frequently proposed as a solution to rising housing costs. However, there is little evidence on how new market-rate construction—which is typically expensive—affects the market for lower quality housing in the short run. I begin by using address history data to identify 52,000 residents of new multifamily buildings in large cities, their previous address, the current residents of those addresses, and so on. This sequence quickly adds lower-income neighborhoods, suggesting that strong migratory connections link the low-income market to new construction. Next, I combine the address histories with a simulation model to estimate that building 100 new market-rate units leads 45-70 and 17-39 people to move out of below-median and bottom-quintile income tracts, respectively, with almost all of the effect occurring within five years. This suggests that new construction reduces demand and loosens the housing market in low- and middle-income areas, even in the short run.

A reasonable logical surmise is that adding even expensive housing to the market increases supply. Rich folks go and occupy that new and expensive housing. The argument in favour of insisting upon those affordable units is that this is where the process stops. Which, of course, it doesn’t.

For those rich folks moving into that new and expensive housing have just vacated a place one step down the market. Which will be moved into by someone else - who has equally just vacated a place and so on.

This cascade down the market means that one new expensive dwelling creates an empty space at the cheapest end of the market. Which is exactly what everyone desires, isn’t it? More and cheaper housing at that bottom end of the market? Something which is, as above, supplied by simply building more houses.

The logical surmise turns out to have empirical support. So we can stop all of the micromanagement of who builds what, where, for which price. Simply build more housing of whatever type and allow the market to sort through the relative valuations. Possibly a simple enough plan for even British politics to be able to grasp it. Possibly…..